In both Soviet times and modern-day Belarus, freedom of expression has never come easily. It has always required a fight—for the right to speak, to write, to testify. This struggle feels especially urgent today, amid sweeping repression, forced exile, and an ongoing information war. That’s why the mission of PEN Belarus remains as relevant as ever: to unite and protect people of the word from censorship, pressure, and injustice. It calls for constant responsibility, dignity, and faith—in language, in literature, and in humanity.

Choosing values over status

PEN Belarus was born out of necessity. It emerged during a turning point in history, when despair and inner tension gave rise to hope for meaningful change. The future was still unclear, but Belarusian writers and intellectuals envisioned an organization built not on party discipline, ideological conformity, or status—but on values: freedom of speech, the right to hold an opinion, accountability for one’s words, and protection of every voice.

The founding committee of this alternative to the official Soviet Writers’ Union included major cultural figures: Sviatłana Aleksijevič, Uładzimir Arłoŭ, Ryhor Baradulin, Vasil Bykaŭ, Hienadź Buraŭkin, Janka Bryl, Uładzimir Niaklajeŭ, Aleś Razanaŭ, Karłas Šerman, and others. Twenty writers in total—and only one of them a woman.

The name “PEN” is not just a reference to the writing instrument—it stands for Poets, Essayists, Novelists. It was these voices that English writers like John Galsworthy, H.G. Wells, and Catherine Amy Dawson Scott sought to bring together when they launched the first PEN Club in 1921. Over time, journalists, researchers, translators, publishers, and playwrights joined too—people who championed human dignity, freedom, and culture through the written word.

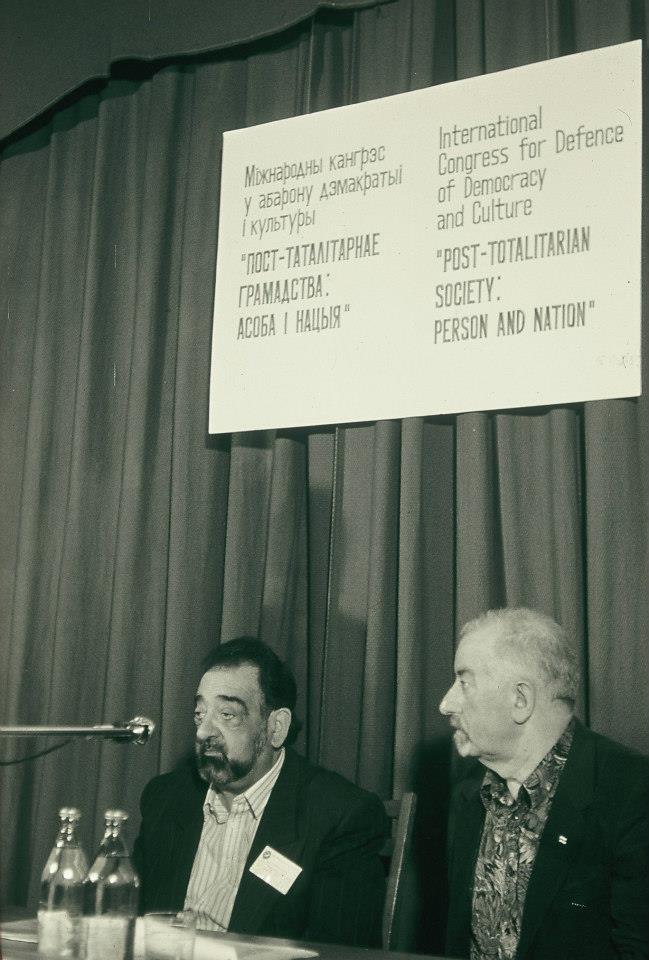

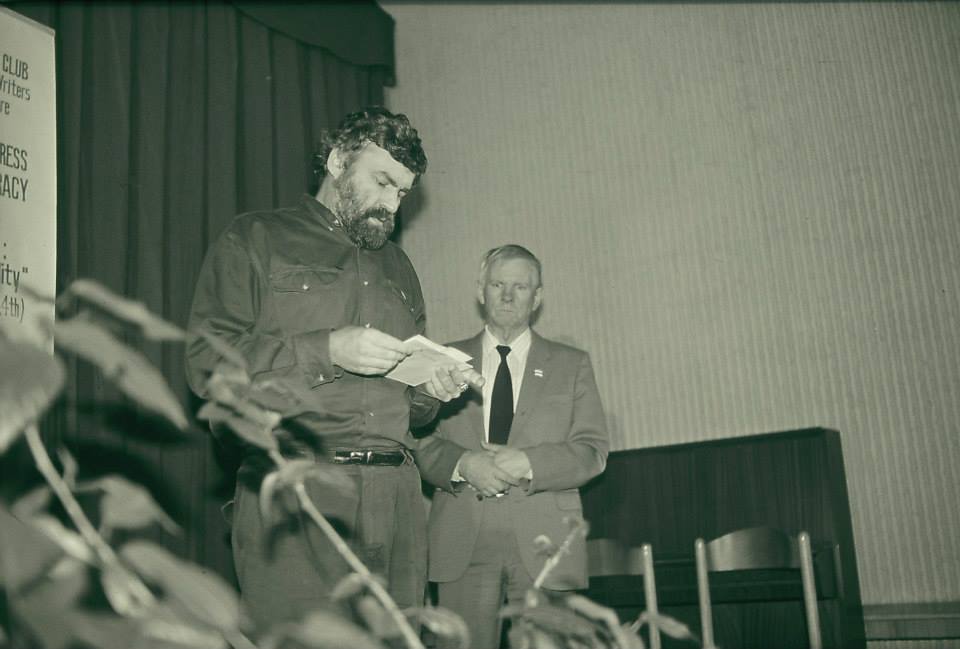

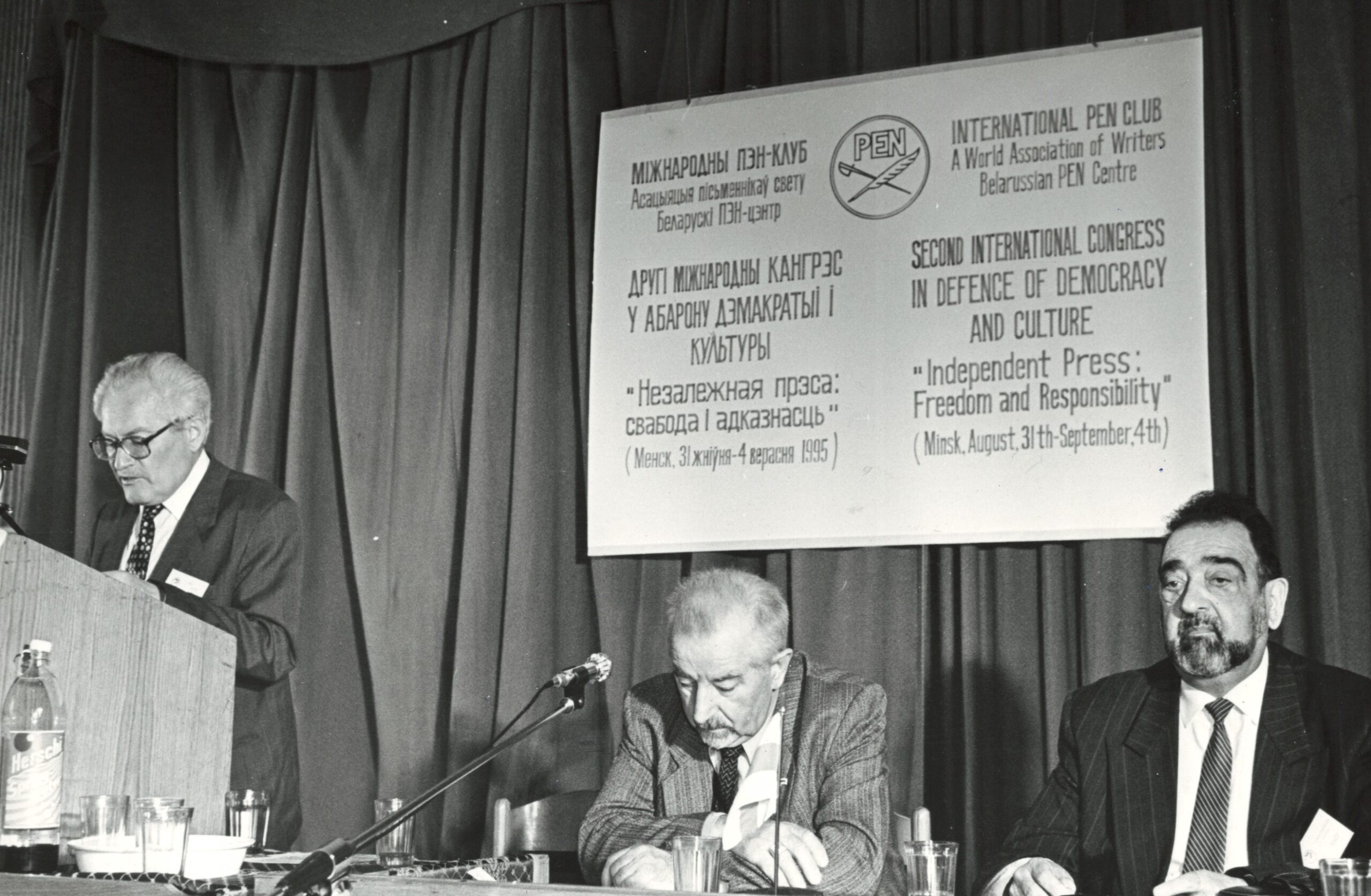

This was their answer to the horrors of World War I: to reach mutual understanding through art, not arms. PEN quickly grew into a global network. In 1990, our PEN joined it—formally founded a year earlier.

Karłas Šerman (Carlos Sherman) — translator, writer, human rights defender—played a key role in this journey. In his memoir The Wanderer, he wrote:

“Independent thought across the USSR was always seen as a kind of original sin. We were constantly accused of thinking the way we did, rather than the way we were supposed to. It’s no coincidence that the PEN Center brought together people who cherished and still cherish free thought. That’s why PEN was treated the way it was. And I believe it always will be.”

Šerman gave PEN Belarus its strong human rights focus and turned it into a center of resistance to the regime, which was gradually reverting to Soviet-style ideology. PEN members spoke out publicly, defended authors’ dignity, challenged silence, monitored censorship, and published the now-famous Yellow Book documenting media persecution in the 1990s.

The PEN Belarus took part in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights, a document primarily created to support languages that are under threat of extinction.

Reflecting on this formative time, Vasil Bykaŭ recalled:

“Our literature and politics have always been closely connected—and that’s not a bad thing. The real question is: what kind of politics? PEN Belarus pursued a national-democratic vision aimed at independence and freedom for the country. It helped found the important human rights organization the Helsinki Committee, where PEN members initially held leading roles. To its credit, PEN Belarus remained united for over a decade without splitting. That’s a rare thing.”

A space for writers

PEN Belarus has never forgotten that literature is its heart. Creativity is what has kept this community alive—it inspires, sustains, and connects generations. Already in the 1990s, the first independent literary prizes appeared: the Aleś Adamovič Prize for journalism and the Francišak Bahuševič Prize for works shaping historical consciousness. Both awards still exist today, serving as symbols of cultural pride and memory.

When Belarusian culture came under the heavy machinery of de-Belarusization, PEN launched a broad educational movement. In the mid-2000s, contests for young writers opened the door to workshops with professional authors, poets, and philosophers. These weren’t just learning opportunities—they were an invitation into the literary world, to creative partnerships, friendships, collective projects, and books.

This wave gave rise to the Maksim Bahdanovič “Debut” Prize—a joint initiative of PEN Belarus, the Belarusian Writers’ Union, and the Viarhannie Foundation. And that was only the beginning: soon followed the Young Writers’ Residency, the poetry festival Vershy na asfaltse (“Poems on the pavement”), and a translation workshop.

The 2010s brought new literary prizes: the Jerzy Giedroyć Prize for the best work of prose; the Natalla Arsiennieva Prize for the best poetry book; the Karłas Šerman Prize for literary translation; the Francišak Alachnovič Prize for works written in imprisonment; and the Michał Aniempadystaŭ Prize for book cover design. Many of these awards were born from partnerships—with the Polish Institute in Minsk, radio stations, the Designers’ Union, the Flying University, and more.

Honoring the best works is not only about recognizing talent. It’s also about asserting that Belarusian literature is here—alive and present in the modern world. When a book receives an award, it’s not only professionally evaluated—it gets read. Often far beyond the borders of Belarus.

Through these efforts, PEN Belarus has built an environment where literature doesn’t close in on itself—it reaches outward, through translations and conversations. Into new generations who keep writing—even when it becomes an openly dangerous act. This is a space where words live and grow.

That includes writing in today’s forced exile. It’s not the ideal soil for literature, but it’s not a void either. The creative process in these conditions is deeply personal—many authors write against all odds. That’s when quiet, friendly support becomes especially meaningful.

Taciana Niadbaj, the current chair of PEN Belarus, reflects:

“These past years have shown us that life is more incredible than literature. What’s happened has matured us—it’s lifted us above ourselves. The creative process is very individual, you can’t speak for everyone. Some keep journals of impressions—poetic diaries that eventually get published. Some, like Sviatłana Aleksijevič, create books in their own signature style. Some keep creating. Others fall silent. Maybe so they can begin again someday, when they feel safe. I’d even say we can be grateful to this reality—it has given us so many emotions and experiences we can now put on paper.”

As a result, we’re witnessing a kind of return—of prose writers, poets, and nonfiction authors—to creating Belarusian literature on a new level. It turns out that deeply traumatic experience can become a foundation both for understanding a time of tragedy and for imagining a future for Belarus.

Literature was, is, and will be: it cannot be “liquidated”

In 2020, the Belarusian regime once again turned to old methods: literature and the broader cultural community were added to the list of those the state sought to silence. Among the main targets was PEN Belarus chairwoman at the time, Sviatłana Aleksijevič, who spoke out openly against violence and lawlessness. As a result, the Nobel laureate was forced to flee the country.

In June 2021, PEN Belarus faced a coordinated bureaucratic assault. The Ministry of Justice requested documents not once but three times—and each time, the organization complied, despite the enormous difficulty of gathering all the required paperwork. Eventually, a raid followed. Then came the court case, which clearly wasn’t about justice—it was a performance, part of a pre-scripted mechanism. Even though every accusation was met with documentation and well-founded arguments, the “judges” ignored them all and rubber-stamped the verdict: liquidation.

Writer and former PEN Belarus chair Andrej Chadanovič observed at the time:

“The regime’s persecution of creative and literary organizations is a form of revenge against Belarusian culture itself—because culture became a symbol of the peaceful protest against violence, lies, and lawlessness. You can exile protesters or drive them underground, but you can’t force people to love or respect a government they no longer believe in. I don’t think there’s any real court in Belarus today, or that its rulings mean anything. But literature in Belarus was, is, and will be—and that cannot be ‘liquidated.’”

Even then, the organization stayed true to itself. In September, PEN Belarus published the Manifesto for an Uncertain Time, declaring its commitment to its mission and values. A new working group held a founding meeting and registered a new legal entity—in Poland. The decision-making center moved abroad, but Belarus remained the center of gravity.

What matters most is what remains: the writers themselves. Writers, scattered across the world, yet united by their language, their culture, and their sense of responsibility. A community that continues to act with heart and intellect, with conscience and talent.

This is not the story of defeat. This is the start of a new chapter.

In exile: defending those who keep culture alive

In the early 2000s, PEN Belarus’s human rights focus faded somewhat, though it remained a moral compass for the organization. But in 2017, when Taсiana Niadbaj became the first woman to lead PEN Belarus, the organization—responding to the pressure of the times and the needs of the community—returned directly to its core mission. Not to replace literature with activism, but to expand its field of action.

It began with documenting the persecution of writers. But it quickly became clear: no one in Belarus was monitoring the situation of artists, musicians, theatre workers, directors… PEN Belarus extended its attention to the entire cultural field—because when culture is repressed, it is repressed in its entirety.

This work is more than just a chronicle. It is a tool of evidence—one that helps communicate with international institutions, reveals the scale of repression, and dismantles myths about the state’s supposed ideological neutrality.

In peaceful times, such analysis could form the basis for dialogue with authorities or arguments for legal reform. Today, it serves as groundwork for the future. Because for now, a shared societal consensus remains out of reach. Still, the work continues—and its moral clarity is unshaken: to defend those who keep culture alive.

During the 2020 uprising, this work became a frontline effort. Repression turned into a daily reality, and PEN Belarus began recording everything—to keep the truth from being lost.

PEN Belarus has always balanced two roles: supporting literature and defending cultural rights. But the latter has become especially urgent. According to PEN monitoring, persecution for dissent is the most widespread human rights violation in Belarus.

The organization defends freedom of expression not just symbolically, but practically. Weekly and monthly reports on violations in the cultural sphere, regular analytical reviews, publications about persecuted artists, support campaigns, and international advocacy—this is ongoing, relentless work. According to PEN’s monitoring data, about 8% of all political prisoners in Belarus are people of creative professions. Many are behind bars simply for using words as a tool of resistance. All known cases are documented; letters of support are sent to victims of the regime; waves of global solidarity are organized in their name; public actions and events are held.

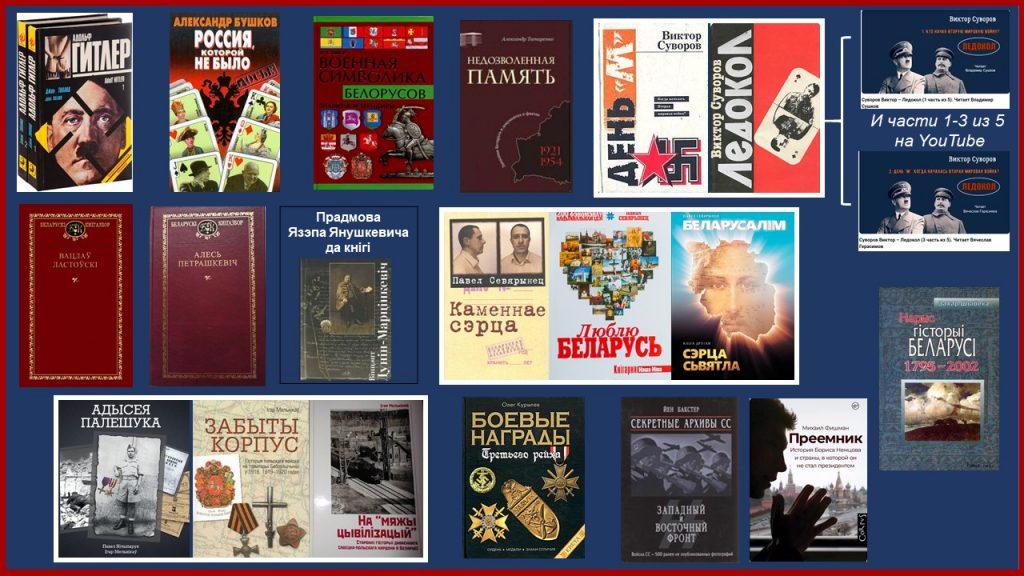

PEN Belarus also maintains a list of literature deemed “extremist.” This is more than just a register of banned books—it’s a map of cultural censorship. It reveals what the regime fears most. At the same time, the organization actively promotes cultural rights: the right to identity, language, and self-expression. Workshops, awareness campaigns, and resources for creative people—and anyone who wants to know how to protect themselves—are all part of its work.

Repression has triggered an unprecedented wave of forced emigration. This created a new challenge for PEN and for cultural figures: not to disappear in foreign cultural spaces, but to preserve themselves and their work.

Yet supporting those in exile is only half the mission. Equally important is caring for the creators who remain in Belarus. These people cannot speak openly. But silence is not absence. PEN Belarus understands the delicate realities they face and supports them discreetly, in solidarity.

One example: a special study explored self-censorship among artists both in Belarus and in exile. It revealed a paradoxical duality. On the one hand, we must talk about a culture of resistance; on the other—a culture of silence, restraint, and anonymity.

Secrecy has become a survival strategy. Internal exile, staying at home, the underground, Aesopian language—all of it has become the new reality of Belarusian culture. People are dismissed, they leave—but they keep creating.

Even though open advocacy inside the country is no longer possible, PEN Belarus continues its work—quietly, but persistently. As a witness, an archivist, a defender. Not for headlines, but to preserve the files of our collective memory. To one day call things by their true names. To lift the curtain of silence and leave a record of this time—of the creators, the literary community. So that in a year, a decade, or even a century, there will be something to return to.

Volha Šparaha, philosopher and PEN Belarus board member, writes:

“The significance of PEN Belarus is hard to overstate. What matters most is that it stands on values—especially mutual understanding among people and communities, including national ones, and the fight against all forms of hatred in the name of peace and equality. Free speech cannot be banned.”

This resilience and devotion to values make PEN Belarus not just an organization, but a moral compass—especially in times when language is under attack, muted, and pushed toward total silence.

Wherever PEN Belarus continues to exist, memory, dignity, and hope are preserved.