Since October 2019, PEN Belarus has been systematically collecting facts about violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures: arbitrary detentions and arrests, searches and interrogations, administrative and criminal sentences, politically motivated dismissals and expulsions from creative unions, refusals to hold events and bans on performances, cases of discrimination based on language, and other violations.

This report aggregates data collected by PEN Belarus’ monitoring team throughout 2024 from open sources and through personal contacts and direct communication with cultural figures under confidentiality. Often, information about violations does not become public and remains within family or professional communities. Therefore, it is important to note that all figures presented in this document represent the minimum threshold for each type of violation.

If you can report cases of repression (including confidentially) or correct any inaccuracies, please contact us at [email protected], t.me/viadoma. The more accurately we can record and analyse the human rights situation in the cultural sphere of Belarus, the more effective our work will be in supporting cultural figures and initiatives. For more information about the monitoring, please check here.

NB: For users’ information security, we do not provide direct links to sources if they are subject to restrictions under the regulations currently in force in the Republic of Belarus.

Main results

Conditions of incarcerated cultural figures

Arbitrary detentions and arrests

Administrative persecution

Criminal prosecution, trials and sentences

Gender dimension of violations

Persecution of exiled figures

Dismissals, a ban on the profession and the practice of vouching

Pressure on organisations and communities in the cultural sphere

Censorship and other violations of cultural rights

State policy in the sphere of culture

Conclusion and recommendations

MAIN RESULTS

The year 2024 marked the third year of imprisonment for Nobel Peace Prize laureate, human rights activist, and literary scholar Aleś Bialacki, along with at least 103 other political prisoners [1] from the cultural field behind bars. Including those serving sentences in home confinement, the number reached at least 168 people by the end of the year.

This year has also seen over 18 months of complete isolation (incommunicado) for imprisoned cultural figures Maksim Znak, Maryja Kalesnikava, Viktar Babaryka, and Siarhiej Cichanoŭski.

Other high-profile violations included:

- The detention of members of the Nizkiz rock band after returning to Belarus from a tour. The band is known for their song, which became an anthem of the Belarusian protest movement in 2020. Administrative and criminal charges followed their detention.

- Repression for acts of solidarity with political prisoners, including the persecution of those providing food parcels and financial aid to them.

- A wave of arrests and searches targeting architects, event agency directors, and leading actors from the Theatre of Belarusian Drama (the latter were subsequently dismissed, depriving one of the country’s most popular theatres of its most in-demand performances), other cultural figures were also targeted.

- Dismissals from key cultural institutions, including the Museum of Traditional Culture in Brasłaŭ, Belarusfilm Studio, and the University of Culture and Arts.

- Politically motivated expulsions from creative unions continued throughout the year.

Transnational persecution intensified:

- In-absentia trials were launched against the independent researchers connected to the so-called “Sviatłana Cichanoŭskaja’s Analysts” case.

- Criminal charges were filed against representatives of the People’s Embassies of Belarus, and Belarusian cultural figures in exile were persecuted for celebrating Freedom Day [2] and participating in elections to the Coordination Council [3]. Their actions resulted in criminal cases, property searches, and seizures of assets owned by political emigrants.

- Acts of vandalism were committed against Belarusian organisations in Vilnius.

- The independent theatre group “Volnyja Kupalaŭcy” was designated as an “extremist formation” [4]. Seven former actors from the Janka Kupała National Academic Theater and director Alaksandr Harcujeŭ were labelled members of this “formation”.

- Belarusian authorities requested the extradition of film director Andrej Hniot from Serbia.

New cases of political and ideological censorship:

- The State Museum of Belarusian Literature’s History prematurely closed an exhibition dedicated to the 100th birthday anniversary of Vasil Bykaŭ.

- The Palace of Arts suspended the exhibition “1.10 Square”, commemorating the 110th anniversary of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square”.

- Censors ordered the removal of the works by several artists from the “Art-Minsk 2024” exhibition, and a theatrical performance was cancelled following a decision by the Public Council on Morality [5].

- Major educational centres were shut down, and civil society organisations faced further forced liquidations.

Expansion of “Extremist” designations:

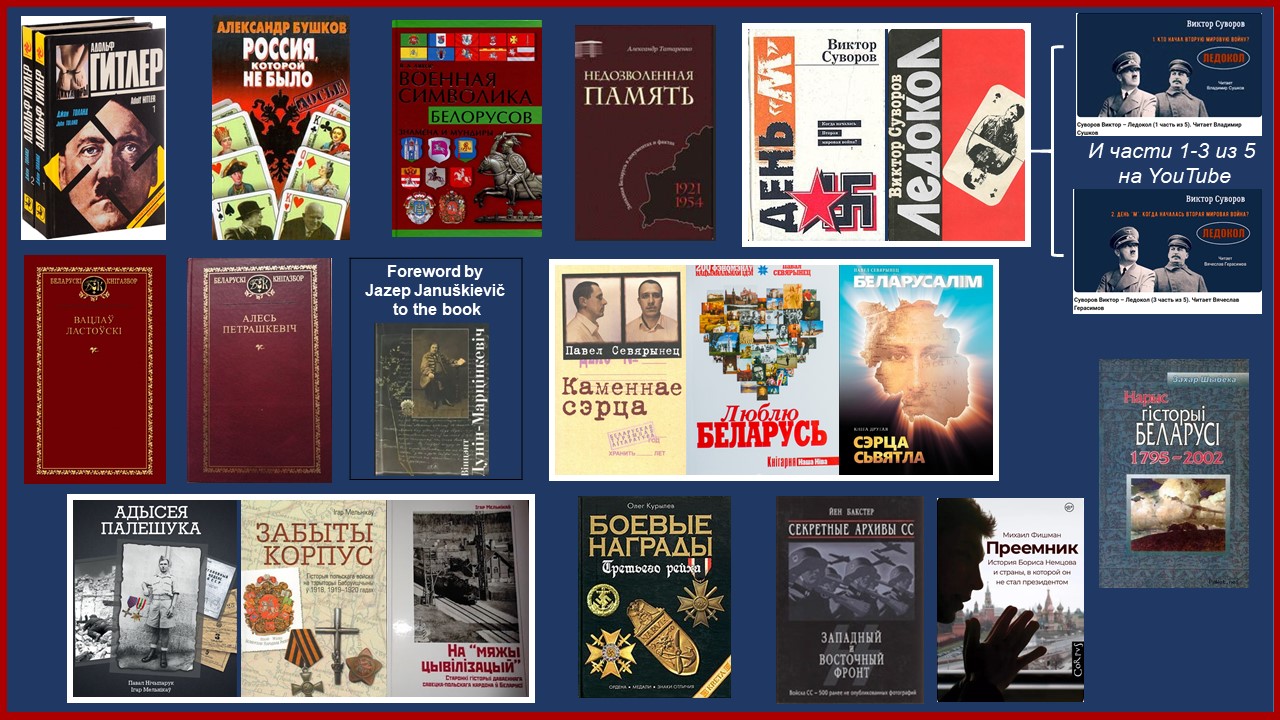

- 19 more books were added to the list of materials deemed “extremist” [6], including works by Pavieł Sieviaryniec, imprisoned since June 2020.

- The YouTube channel of poet and translator Andrej Chadanovič, dedicated to Belarusian literature, was labelled extremist.

- The YouTube channel about Belarusian culture and social media accounts run by Mikita Monič, an art historian dismissed from the National Art Museum of Belarus in 2020 for political reasons – were also banned as extremist.

- The music video and lyrics of Nie Być Skotam (Don’t Be Cattle) by the band Lyapis Trubetskoy, based on the 1908 poem Chto Ty Hetki? (Who Are You?) by Belarusian national poet Janka Kupała, were labelled “extremist”.

The Ministry of Information banned 35 books, mostly related to LGBT themes and anime, mainly published by Russian publishers. More historical and cultural heritage sites were destroyed, and discrimination against the Belarusian language persisted. Repression for using national symbols – the white-red-white flag and the Pahonia coat of arms – continued.

2024 marked the 30th year of Alaksandr Łukašenka’s rule. The official celebrations orchestrated for this anniversary were a stark illustration of how culture has been transformed into a tool for serving the regime.

At the end of the year, a new Minister of Culture was appointed, with Lukashenka giving him a clear directive: “Either die or bring order to this sector”.

Persecutions in 2024: Figures and Trends

- Total number of violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures: at least 1348

- Top 10 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures

Violations of the right to a fair trial and the designation of culture-related materials (or social media pages of cultural figures) as “extremist” were the most common violations observed by the monitoring team.

For cultural figures – violations of the right to a fair trial (311 cases), arbitrary detentions/arrests (129), and criminal prosecution (117).

For organisations and communities – the most frequently recorded violations included administrative obstruction, including forced liquidation (85 cases), and violations of the right to a fair trial and freedom of association (39 cases, correspondingly).

- Cultural figures behind bars or with restricted freedom

As of 31 December 2024, at least 104 political prisoners from the cultural sphere were behind bars. According to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, Belarus had a total of 1,265 political prisoners. At least 168 cultural figures, including 37 People of Word (writers, poets, culture journalists, etc.), were either imprisoned or serving their home confinement terms.

- Cultural figures recognised as political prisoners and released

In 2024, at least 56 cultural figures were recognised as political prisoners, including 7 people post facto [7]. At least 49 were released during this period, including 34 cultural figures who completed prison sentences ranging from one to four years, 14 who were granted early release through pardons [8], and one person (a Ukrainian citizen) released through a prisoner exchange [9].

- Arbitrary detentions and arrests, administrative punishment and criminal prosecution

At least 129 cultural figures were arbitrarily detained or arrested. 95 cultural figures were subjected to administrative punishment (the police filed 105 administrative offence reports). At least 117 cultural figures faced criminal prosecution. In 20 cases, special proceedings were initiated, i.e. trials in absentia against individuals who had fled Belarus for safety. At least 88 cultural figures were convicted, including 75 through in-person trials and 13 via trials in absentia.

- Cultural figures listed as “terrorists” and “extremists”

7 cultural figures were included in the “List of Organisations and Individuals Involved in Terrorist Activities”, 64 – to the “List of Belarusian Citizens, Foreign Citizens, or Stateless Persons Involved in Extremist Activities”.

- Politically motivated dismissals

It is known about politically motivated dismissals of 45 cultural figures.

- Forced liquidation of non-profit cultural organisations

At least 39 cultural associations were forcibly dissolved.

- “Extremist materials”

The Belarusian Ministry of Information added at least 289 culture-related materials or social media accounts of cultural figures to the “List of Extremist Materials”.

- Censorship

133 censorship cases were recorded, affecting art exhibitions, concerts, theatre plays, film screenings, books, and public performances.

- Violations related to historical and cultural heritage and historical memory

55 violations concerning the preservation of heritage sites (officially designated as historical-cultural monuments and those without such status) and the culture of remembrance were documented.

- Trends and forms of persecution:

-

- Compared to 2023, significantly fewer cases of arbitrary detention and administrative prosecution were recorded in 2024, while special proceedings (trials in absentia) and convictions in absentia increased [10].

- The most common reason for criminal prosecution was participation in the 2020 peaceful protests. The “distribution of extremist materials” was predominantly the reason for administrative punishment.

- Criminal prosecution for donations to solidarity funds and paramilitary organisations continues. There are reports of repeated interrogations even after individuals paid the “compensation amounts” set by security agencies and had their criminal cases closed.

- Criminal prosecution for collaboration with independent media (including interviews) remains ongoing. Many trials are held behind closed doors, making it difficult to determine the exact charges under allegations of facilitating extremism or participating in extremist activities.

- Supporting political prisoners is now considered facilitating extremism – with courts sentencing people to prison for transferring money or sending parcels to political prisoners.

- The number of repeat offenders among cultural figures is increasing. Repression continues even in prison, with political prisoners facing additional charges.

- Individuals returning to Belarus after living abroad continue to face arrest and prosecution.

- Punishments became harsher in 2024, with home confinement increasingly replaced by imprisonment in penal colonies. The number of such sentence escalations has risen, including for individuals who left Belarus after being convicted.

- Persecution of Belarusians in exile has intensified.

- The first known case of repeated special proceedings (trial in absentia) against a cultural figure was recorded.

- Authorities have resumed the practice of criminal prosecution for involvement in unregistered or liquidated organisations under Article 193-1 of the Criminal Code.

- A new precedent was set: an email address was declared “extremist material”. The email [email protected] – belonging to the independent theatre troupe “Volnyja Kupałaŭcy” – was added to the “List of Extremist Materials”.

- A new category of banned literature emerged: the Ministry of Information published a list of printed publications prohibited in Belarus for allegedly “potentially harmful to national interests”.

- For the first time, a court reversed a book’s “extremist material” designation. On 11 March 2024, a court overturned the 8 November 2023 ruling that had labelled a two-volume collection of works by Belarusian literary classic Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič as “extremist”.

CONDITIONS OF INCARCERATED CULTURAL FIGURES

The persecution of cultural figures continues even in places of incarceration. “Special treatment” conditions are created for those serving home confinement sentences. Those who have walked out after serving their terms are not left alone.

By the end of 2024, at least 168 cultural figures in Belarus were either behind bars or in home confinement.

In 2024, violations of conditions in the places of incarceration were recorded in relation to 40 individuals. This is undoubtedly only a fraction of the persecution that cultural figures imprisoned for political reasons face daily. Over time, former political prisoners have become the primary source of information about torture and inhumane treatment in places of incarceration after their release.

Information blackouts, isolation from other prisoners, placement in solitary confinement, punitive confinement, transfer to a stricter prison regime, deprivation of correspondence and care packages, bans on purchasing goods, disciplinary sanctions, provocations, forced hard labour, and denial of outdoor walks – all these apply to those serving criminal sentences. For administrative detainees, the situation includes overcrowded cells, lice, bedbugs, extreme cold, sleeping on the floor, daily searches with belongings scattered, nighttime inspections, placement with homeless individuals, and strip searches. These are just some of the physical and psychological pressures imposed on political prisoners, turning their imprisonment into a daily struggle for survival. Deterioration of health, in some cases rapidly worsening, is one of the consequences of these conditions and the mistreatment of the cultural figures behind bars.

At least 14 cultural figures with serious health issues remain imprisoned: Viktar Babaryka, Aleś Bialacki, Jaŭhien Burło, Alena Hnaŭk, Uładzimir Hundar, Hienadź Drazdoŭ, Ihar Jarmołaŭ, Dzianis Ivašyn, Maryja Kalesnikava, Uładzimir Mackievič, Vacłaŭ Areška, Alaksiej Parecki, Andrej Pačobut (Andrzej Poczobut), and Alaksandr Fiaduta. Despite their conditions, they are forced into hard labour, frequently placed in solitary confinement, and subjected to a stricter prison regime. Testimonies from released prisoners indicate that medical assistance is either nonexistent, delayed, or inadequate.

Total isolation (incommunicado) means a prisoner is cut off from the outside world: no contact with family, friends, lawyers, or fellow inmates.

As of December 31, 2024, lawyer, writer, and bard Maksim Znak has been in an information blackout for 692 days (the last letter his family received was dated 9 February 2023). Cultural manager, video blogger, and political figure Siarhiej Cichanoŭski has been isolated for 663 days (since 9 March 2023). Musician, cultural projects manager, and public figure Maryja Kalesnikava endured 639 days incommunicado before Belarusian authorities permitted her to meet her father on 12 November 2024. Since then, communication with her has ceased again. Philanthropist and political figure Viktar Babaryka [11] has been cut off from communication for 616 days (since 26 April 2023). Anarchist and prison literature author Alaksandr Franckievič has been in total isolation for 70 days (since late October 2024). Activist and local history amateur Uładzimir Hundar was held incommunicado from May to August 2024.

Punitive confinement is used as a punishment and form of pressure. In Belarusian prisons, it is a tiny cell with a cement floor, minimal furniture, freezing temperatures in winter, extreme heat in summer, constant artificial lighting, and a lack of outdoor walks and other restrictions.

According to the Viasna Human Rights Center, musician and IT specialist Vadzim Hulevič spent nearly three months in punitive confinement (from 10 November 2023 to the end of January 2024). Journalist Andrej Pačobut (Andrzej Poczobut) was consecutively placed in punitive confinement for several months. As of August 2024, anarchist and prison literature writer Mikałaj Dziadok had already spent two months in punitive confinement. Poet, bard, and lawyer Maksim Znak is almost constantly placed there. Dzmitry Daškievič, an activist and publicist, was placed in punitive confinement after being transferred to a penal colony in January 2024. It was so cold inside that he had to wake up every hour and exercise just to stay warm – an action for which he was disciplined for violating the nighttime rest regime. Other cultural figures placed in punitive confinement include Aleś Bialacki, Ihar Alinievič, Dzmitry Kubaraŭ, Alaksiej Kuźmič, Dzianis Ivašyn, and Natalla Piatrovič.

! On 12 July 2024, a new law came into force in Belarus, increasing the maximum single period in punitive confinement from 10 to 15 days.

A cell-type room is a long-term solitary isolation unit inside a prison similar to punitive confinement, where prisoners are denied parcels and visits. In 2024, a cell-type room was used against Maryja Kalesnikava, Eduard Babaryka, Andrej Pačobut, Artur Amiraŭ, Rusłan Łabanok, Ihar Karniej, and Maksim Znak.

Temporary transfer to a stricter prison regime is yet another form of isolation with even harsher conditions than penal colonies. Courts ruled a stricter prison regime for Michaił Łabań, owner of the “Samarodak” jewellery workshop (in May 2024) and writer and programmer Alaksiej Navahrodski (in December 2024).

Sentence extension by opening new criminal cases under Article 411 of the Criminal Code (persistent disobedience to prison administration) is another form of persecution and punishment. In 2024, at least six cultural figures received extended sentences under Article 411: Eduard Babaryka, Ivan Viarbicki, Dzmitry Daškievič, Alaksandr Franckievič, Pavieł Spiryn, and Ihar Karniej. Additional sentences ranged from eight months to two years in prison. For Ivan Viarbicki, this was a repeated politically motivated sentence extension.

After being held in the conditions created for political prisoners in Belarusian prisons, cultural figures often leave places of incarceration with deteriorated eyesight, severe dental issues, exacerbated chronic illnesses, and other serious health problems – sometimes critical and irreversible. On 22 September 2024, punk musician Viktar “Mao” Žarkievič died at his home due to heart failure, reportedly caused by severe health deterioration after his brutal detention in September 2022 and 13 days in the detention centre on Akrescina Street in Minsk.

In May 2024, a report by the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Belarus, Anaïs Marin, highlighted numerous instances of callous treatment of prisoners incarcerated for political.

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS AND ARRESTS

In 2024, there were 129 documented arbitrary detentions (or arrests) of cultural figures – musicians and artists, architects and writers, ethnographers and sound engineers, photographers and actors, event hosts and directors of event agencies, illustrators and historians, designers and librarians, artisans and local historians, humanities teachers, and other representatives of Belarusian culture.

Group detentions targeted professional or social groups, such as architects, event hosts, event agency directors, regional journalists, actors. Sometimes, married couples were detained together, as was the case with artists Ludmiła Ščamialova and Ihar Rymašeŭski. Detentions are often carried out brutally: when video operator and journalist Jaŭhien Hłuškoŭ did not open his door, police operatives stormed his apartment, dragging him outside in his home clothes. The former head of the Jewish community, Raman Smirnoŭ, was detained by Typhoon special unit commandoes.

Some detained cultural figures were forced to record so-called “repentant videos”, a humiliating and inhumane practice by security forces. One such case occurred on 5 January 2024, when members of the Nizkiz rock band were detained immediately upon returning to Belarus from a tour. The musicians were forced to “confess” on camera that they had gone out during the 2020 protests “to participate in riots”, performed songs for protesters, including for the independent media outlet Belsat.

Under duress, detained cultural figures were forced into “confessing” to a variety of actions: participating in the 2020 protests, stepping onto the roadway during demonstrations, taking pictures with the white-red-white flag, and posting critical comments about the authorities on social media. They were also forced to admit to registering in the Pieramoha (Victory) chat-bot [12], sending data on police officers and other government officials to the “Black Book of Belarus” [13] Telegram channel, voting for Sviatłana Cichanoŭskaja in the 2020 elections, expressing negative views about Russian soldiers and supporting Ukraine, subscribing to groups labelled “extremist” by the regime, and other similar “violations”. In some cases, they were compelled to disclose their sexual orientation or income level, “repent” for their actions and publicly apologise.

We do not have information about the fate of every fifth detained cultural figure: whether they faced administrative punishment, criminal cases were opened against them, or they were released. This is just one of the current trends – significant difficulties or prolonged delays in obtaining reliable data on repressions. For example, it wasn’t until mid-January 2025 that information surfaced about an upcoming criminal trial against choir member Daniel-Landsey Keita, who had been detained in Hrodna as far back as June 2024. And there are many such stories.

ADMINISTRATIVE PERSECUTION

The People’s Master of Belarus, director of a puppet theatre, leader of the best cultural collective in the district, Person of the Year of Viciebsk Region, winner of the district competition “Teacher of the Year 2014”, best cultural worker of Prydvińnie, a well-known accordionist in the Haradok district, director of the rural House of Culture, and dozens of other cultural figures faced politically motivated administrative persecution – receiving fines or being sentenced to administrative arrest – in 2024.

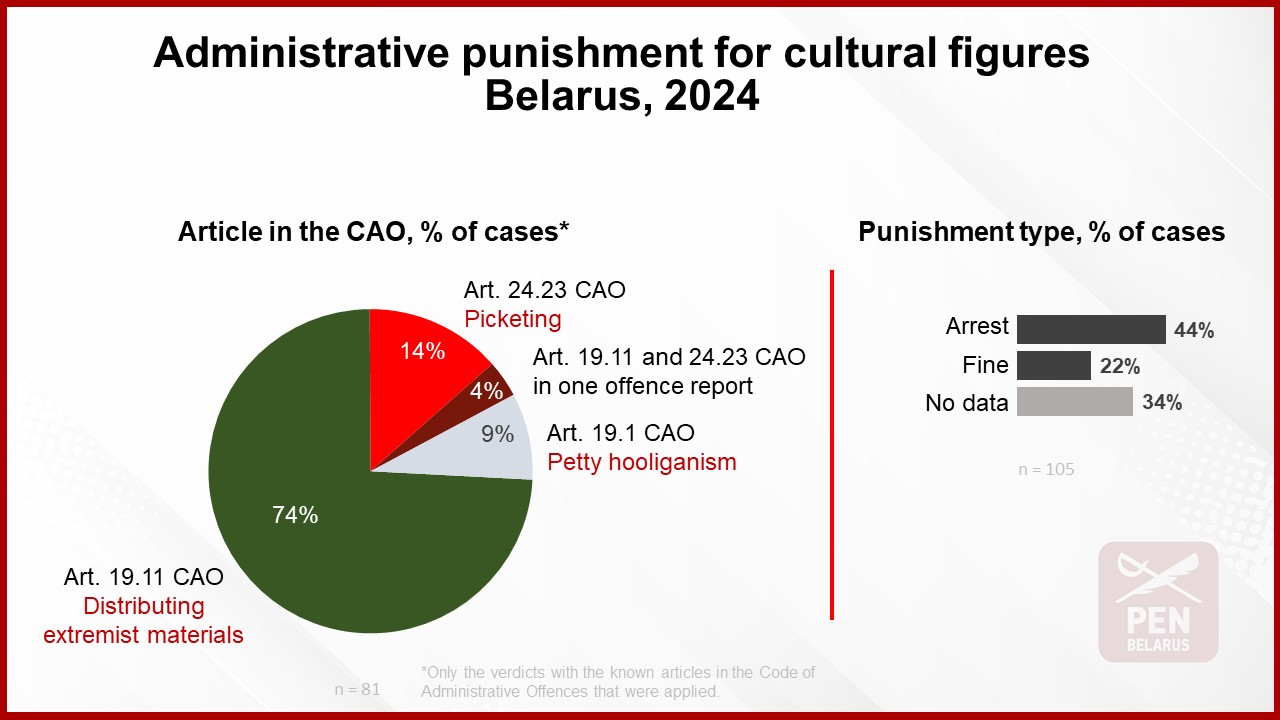

In 2024, courts heard at least 105 administrative cases against 95 cultural figures. The articles under which individuals were held accountable are known in 81 cases.

In 74 % of cases (60 offence reports), punishment was related to the alleged distribution of extremist materials (Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences) – for subscriptions to independent media and platforms on social networks (Zerkalo, Radio Svaboda, Novosti Grodno, Honest People, and others), as well as for using the logos of Belsat, Euroradio, and other independent news outlets in their profiles. In such cases, cultural figures were subjected to administrative punishment by arrest for 5–15 days or fines between 400 and 5,400 BYN (~117–1,580 USD).

There were documented cases where subscriptions to prohibited content appeared on a person’s phone after police or other security officials checked it.

Almost in 14 % of known rulings (11 offence reports), courts issued administrative penalties (days of arrest or fines) for alleged picketing on social networks – displaying the white-red-white flag or the ‘Pahonia’ coat of arms (Article 24.23 of the Code of Administrative Offences). For example, one Belarusian writer was fined 1,400 BYN (~410 USD) for “posting a graphic image with the design of a white-red-white banner with the ‘Pahonia’ coat of arms, thus publicly expressing his personal and other interests regarding the events of socio-political life <...> without the appropriate permission of local executive and administrative bodies”. The use of the term “banner” in official documents also reflects the current authorities’ attitude towards historical heritage.

In some cases, cultural figures were punished under the article dealing with “petty hooliganism” (Article 19.1 of the Code of Administrative Offences). They were accused of using foul language, displaying aggressive behaviour, waving their arms, and ignoring police warnings. All charges were formulated in a template manner as if copied. Punishments ranged from 13 to 15 days of arrest for actions that, judging by the circumstances, none of the accused committed.

In two out of three cases, courts issued arrest rulings, and almost every second verdict envisaged 15 days of arrest – the maximum punishment.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION, TRIALS AND SENTENCES

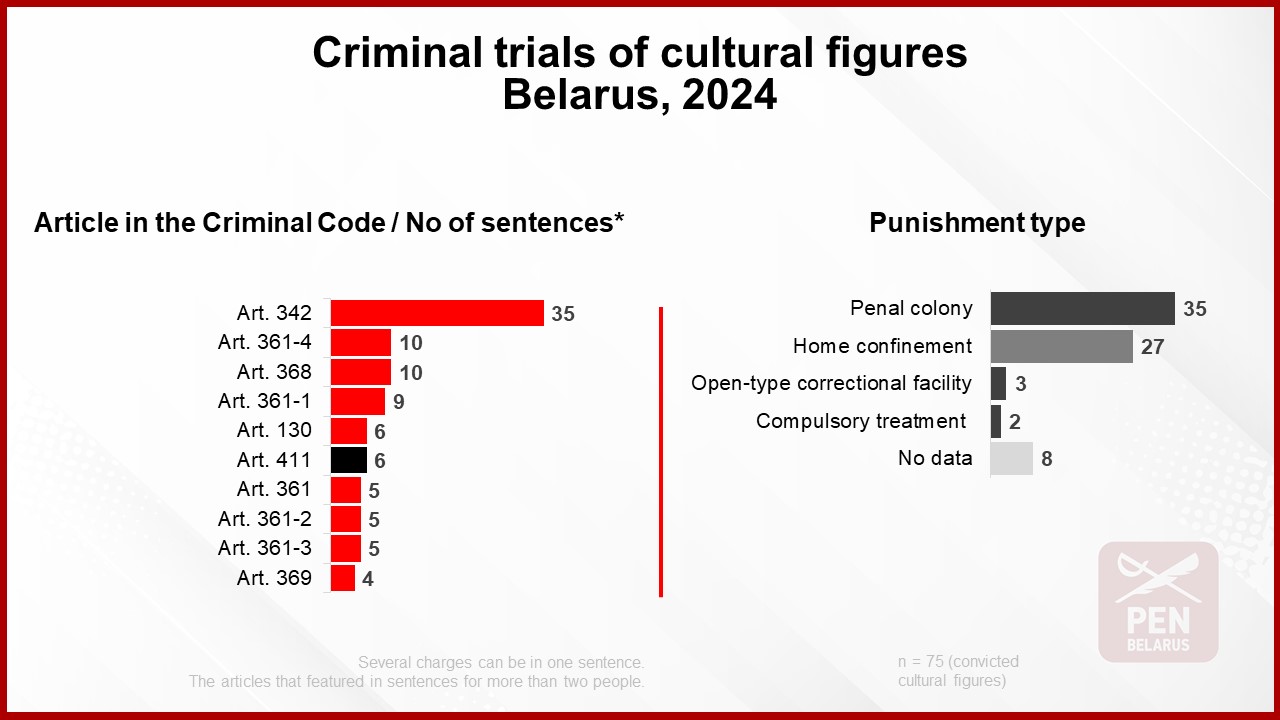

In 2024, at least 117 cultural figures were subjected to criminal prosecution, 88 people who were convicted. One in three recorded cases and one in seven sentences involved political emigrants – more details in the Persecution of Exiled Figures section. This one focuses on repressions within the country.

In 2024, courts issued at least 77 sentences to 75 cultural figures. Musician Dzmitry Šałak [14] and journalist, author of texts on Belarus’s cultural and historical heritage, Ihar Karniej, were convicted twice during the reporting period. This was not the first sentence for eight individuals convicted in 2024; some received their third or fourth “court” verdict.

Participation in the 2020 peaceful protests remained the most common reason for criminal prosecution. Article 342 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (Organising, preparing or actively participating in actions that grossly violate public order) featured in the charges against nearly every second convicted cultural figure (35 people). 31 individuals were convicted solely under this article, with most (24 cultural figures) sentenced to home confinement for terms between 30 and 36 months. Event host and cultural manager Jahor Zienčanka, Belarusian language teacher Alena Stachiejka, tour guide Alaksandr Nikicin, and break-dancer and worker Dzmitry Michalcevič received between one and two years in a penal colony under this article. Musician Dzmitry Hłuščanka was sentenced to restricted freedom in an open-type institution (pardoned in December 2024).

The second most frequently applied charges were “facilitating extremist activities” (Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code) and “insulting the president of the Republic of Belarus” (Article 368 of the Criminal Code). These articles featured in the cases against ten cultural figures. Six people were convicted solely under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code. Musician Hleb Dudko, historian Ihar Mielnikaŭ, librarian Iryna Pahadajeva (pardoned in December 2024), and English language tutor Larysa Katovič were sentenced to imprisonment. Designer Natalla Kremis and craftswoman Natalla Charytonava-Kryževič were punished with home confinement.

In most cases, the grounds for prosecution remain unknown, partly due to the closed nature of trials. It is only known that Iryna Pahadajeva was convicted for expressing solidarity with political prisoners (more details in the section describing the Gender dimension of violations). When the accused was brought into the courtroom, the judge requested that her handcuffs be removed. Still, the convoy referred to an order from the Ministry of Internal Affairs requiring defendants under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code to remain cuffed. Historian and Ph.D. in history Ihar Mielnikaŭ was convicted for his interviews and comments to Euroradio [15] in 2022. Back in the time, the regime had not yet designated this media outlet an “extremist formation”. One month before the sentence, three of Mielnikaŭ’s scientific books were included in the list of “extremist materials”. Three cultural figures – sound engineer Dzmitry Famin, former head of the Jewish community Raman Smirnoŭ, and photographer Uładzisłaŭ Košaleŭ – were convicted under Article 368 of the Criminal Code.

Charges of allegedly “creating or participating in an extremist formation” (Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code) featured in the cases against nine cultural figures. Five people were convicted solely under Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code. For example, journalist Ihar Karniej, engineer and architectural photo database creator Uładzimir Fišman, photographer and documentary filmmaker Alaksandr Ziańkoŭ, linguist Nastassia Maciaš (pardoned in December 2024), and event host Jaŭhien Sciapanaŭ were sentenced to two or three years in a penal colony. According to the prosecution, Ihar Karniej cooperated with the Belarusian Association of Journalists – a public association forcibly liquidated in August 2021 and declared an “extremist formation” by the KGB in 2023. The punishment he received was three years in a penal colony and a 20,000 BYN (~6,000 USD) fine. Linguist Nastassia Maciaš was convicted for language consultations, translations, and text editing she did for Belsat. She received two years in a penal colony, was fined 20,000 BYN, and was ordered to pay 102,415 BYN (~30,000 USD) as compensation for allegedly illegal income.

Of the 75 convicted cultural figures:

- 35 were sentenced to terms in a penal colony,

- 27 were punished with home confinement,

- 3 were sentenced to restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility,

- 2 were sentenced to compulsory treatment in a mental facility,

- Information on sentences for 8 individuals we don’t

Convictions by month in 2024:

January: engineer and architectural photo database creator Uładzimir Fišman (incriminated under Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code (CC), penal colony [16]); writer, poet and activist Aleh Kacapaŭ (Articles 130 and 368 of the CC, 2.5 years in a penal colony); photographer Alaksandr Vasiukovič (Article 342 of the CC, 3 years in home confinement); photographer and documentary filmmaker Arciom Ziankoŭ (Article 342 of the CC, 3 years in a penal colony).

February: musician Dzmitry Šałak (Articles 368 and 369 of the CC, – [17]); artist Hanna Kruk (Article 342 of the CC, 3 years in home confinement); graduate from BSU’s Culturology Department Ksienija Chodyrava (Articles 361-2 and 361-3 of the CC, 5 years in a penal colony); musician Jaŭhien Šum (Article 342 of the CC, 3 years in home confinement).

March: artist Uładzimir Łykšyn (Article 342 of the CC, 2.5 years in home confinement); musicians Alaksandr Iljin, Dzmitry Chalaŭkin and Siarhiej Kulša (Article 342 of the CC, 2.5 years in home confinement for each); journalist and author of texts about the cultural and historical heritage of Belarus Ihar Karniej (Article 361-1 of the CC, 3 years in a penal colony and a 20 000 BYN fine); writer and cultural manager Siarhiej Makarevič (Article 361-2 of the CC, 2 years in open-type correctional facility); English language tutor Larysa Katovič (Article 361-4 of the CC, penal colony).

April: Belarusian language teacher Alena Stachiejka (Article 342 of the CC, 1 year in a penal colony); linguist Nastassia Maciaš (Article 361-1 of the CC, 2 years in a penal colony and a 20 000 BYN fine); poet, cultural events organiser and journalist Aksana Jučkavič (Article 342 of the CC, 3 years in home confinement); writer, translator from Chinese to Belarusian Darja Chmialnickaja (Articles 342 and 361-3 of the CC, 5.5 years in a penal colony); event host and cultural manager Jahor Zienčanka (Article 342 of the CC, 2 years in a penal colony); actors Hražyna Bykava-Nazdryna and Uładzisłaŭ Nazdryn (Article 342 of the CC, 2.5 years in home confinement for each).

May: photographer Alaksandra Mielničak (Articles 342 and 130 of the CC, penal colony); artist and animator Ivan Viarbicki (Article 411 of the CC, additional 2 years in a penal colony); DJ Arciom Makaviej (Article 358-1 of the CC, 6 years in a penal colony); English language teacher Milena Mielnik (Article 342 of the CC, home confinement); musician Aleh Ladzienka (Article 342 of the CC, 2.5 years in home confinement); ceramist Alena Karpienka (Article 367 of the CC, 1.5 years in a penal colony).

June: craftswoman and artist Nelli Ałfiorava (Article 369 of the CC, forced treatment in a mental facility); writer, poet, translator and doctor Alena Cieraškova (Article 342 of the CC, 3 years in home confinement); Belarusian language and literature teacher Rusłan Pracharenka (Articles 356, 130, 361-4 and 406 of the CC, 10 years in a penal colony); musician Rusłan Praŭda (Article 342 of the CC, home confinement); writer and anarchist Alaksandr Franckievič (Article 411 of the CC, additional one year in a penal colony); architects Darja Mandzik, Illa Pałonski and Raman Zabieła (Article 342 of the CC, 2.5 years in home confinement for each); film director Rusłan Zholič (Articles 368 and 369 of the CC, forced treatment in a mental facility).

July: librarian Iryna Pahadajeva (Article 361-4 of the CC, 3 years in a penal colony); cultural manager and businessman Eduard Babaryka (Article 411 of the CC, additional 2 years in a penal colony); musician and startup entrepreneur Hleb Dudko (Article 361-4 of the CC, penal colony); break-dancer and worker Dzmitry Michalcevič (Article 342 of the CC, 1 year in a penal colony); illustrator Natalla Levaja (Articles 361-1, 361-2 и 361-3 of the CC, 6 years in a penal colony); musician and photographer Dzmitry Sačyŭka (Article 342, home confinement); vocalist Rusłan Musvidas (Article 342 of the CC, home confinement); musician Uładzimir Navumovič (Articles 368 and 361-1 of the CC, –); cultural blogger Aleś Sabaleŭski (Article 361-1 and 361-3 of the CC, 4 years in a penal colony); documentary filmmaker and video operator Jaŭhien Hłuškoŭ (Articles 361-1 and 361-3 of the CC, 3 years in a penal colony); event host Pavieł Paškievič (Article 342 of the CC, –).

August: crafts designer Natalla Kremis (Article 361-4 of the CC, home confinement); musician Dzmitry Šałak (Articles 368 and 369 of the CC, 3.5 years in a penal colony); craftswoman Natalla Charytonava-Kryževič (Article 361-4 of the CC, 5 years in home confinement); musician and IT-specialist Dzmitry Hłuščanka (Article 342 of the CC, home confinement); former head of the Jewish community Raman Smirnoŭ (Article 368 of the CC, –).

September: former bibliographer of the National Library Ksienija Suša (Article 361-4 and 361 of the CC, 3 years in a penal colony); historian Ihar Mielnikaŭ (Article 361-4 of the CC, 4 years in a penal colony); publicist and activist Dzmitry Daškievič (Articles 342 and 411 of the CC, additional one year and three months in a penal colony); event host Jaŭhien Sciapanaŭ (Article 361-1 of the CC, –); screenwriter and musician Kirył Vieviel (Article 361 of the CC, 3 years in a penal colony); tour guide Alaksandr Nikicin (Article 342 of the CC, penal colony).

October: book printer Aleh Syčoŭ (Article 289 of the CC, 9 years in a penal colony); designer Siarhiej Skibinski (Articles 342 and 361-4, penal colony); sound engineer Dzmitry Famin (Article 368 of the CC, 3 years in home confinement).

November: photographer Arciom Ziańkoŭ (Article 361-2 of the CC, –); photographer Uładzisłaŭ Košaleŭ (Article 368 of the CC, 3 years in open-type correctional facility); blogger and documentary filmmaker Pavieł Spiryn (Article 411 of the CC, additional one year in a penal colony); architect and musician Alaksiej Silenka (Articles 361 and 130 of the CC, –).

December: English language translator and tutor Siarhiej Harłoŭ (Articles 361, 368, 130 and 361-4 of the CC, –); linguistics student of Baranaviči State University Hanna Kurys (Articles 370, 368, 130 and 369-1 of the CC, –); musician Ivan Vabiščevič (Article 342 of the CC, 2.5 years in home confinement); Ihar Karniej (Article 411 of the CC, additional 8 months in a penal colony); musician and businessman Armen Arzumanian (Articles 361 and 367 of the CC, penal colony); comedian and event host Sciapan Mankievič (Article 342 of the CC, –).

At least five other cultural figures are known to have undergone trials.

GENDER DIMENSION OF VIOLATIONS

As of 31 December 2024, at least 19 female political prisoners who are cultural figures remained in penal colonies, detention centres, or under compulsory treatment (11.3 % of the total number of women behind bars). Additionally, at least 30 people are serving sentences in home confinement.

In total, at least 49 female cultural figures (30 % of all cultural sector workers deprived of or restricted in their freedom) are in places of incarceration or home confinement. Among them are at least 8 writers:

- political scientist and publicist Valeryja Kasciuhova (sentenced to 10 years in a penal colony),

- writer and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvałava) (8 years and three months in a penal colony),

- local historian and documentary filmmaker Łarysa Ščyrakova (3.5 years in a penal colony),

- writer, poet, translator and doctor Alena Cieraškova (3 years in home confinement),

- poetess and cultural manager Aksana Jučkavič (3 years in home confinement),

- philologist and writer Natalla Sivickaja (3 years in home confinement),

- philologist and writer Nadzieja Staravojtava (3 years in home confinement),

- writer and journalist Jana Cehła (2 years in home confinement).

From July to December 2024, at least 13 cultural figures were released from prisons under pardons. The following 11 of them were women:

- senior lecturer at the Department of Foreign Literature at Minsk State Linguistic University Natalla Žłoba,

- documentary film director and journalist Ksienija Łuckina,

- dancer and entrepreneur Viktoryja Haŭrylina,

- historical archive employee Natalla Piatrovič,

- urbanist and geographer Hanna Skryhan,

- Russian language and literature teacher Ała Zujeva,

- foreign languages student at Mahiloŭ State University Danuta Pieradnia,

- writer and translator Darja Chmialnickaja,

- ceramist Alena Karpienka,

- librarian Iryna Pahadajeva,

- linguist Nastassia Maciaš.

On 28 June 2024, Chinese language translator Kaciaryna Bruchanava was released in a prisoner exchange.

Repressions against women in culture

In 2024, one in three recorded cases of repression or censorship involved female cultural figures. At least 153 women from this sphere were subjected to persecution.

- Nearly every second (22 out of 46) documented politically motivated dismissal in the cultural sector (museums, theatre, music, cinema, education, etc.) affected women.

- Administrative persecution was recorded against 35 female cultural figures. In 57 % of known cases, they received fines ranging from 400 to 5,400 BYN. The main charge was “distribution of extremist materials” (Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences of the Republic of Belarus), which accounted for 85 % of offence reports.

- Courts convicted at least 24 female cultural workers (32 % of convicted cultural figures). Among them:

- 10 people received sentences between one and six years in a penal colony.

- 12 were sentenced to 2.5–5 years in home confinement.

- 1 woman was sent for compulsory treatment.

- The court ruling for one person remains unknown.

In at least half of the cases, the charges included the “people’s” Article 342 of the Criminal Code (organising, preparing or actively participating in actions that grossly violate public order) for participation in the 2020 protests (13 out of 24 convicted). In every fifth case (5 out of 24), Article 361-4 (facilitating extremist activities) was applied – most often for showing solidarity with political prisoners.

In 2024, all those convicted for helping political prisoners and themselves becoming prisoners were women. These cultural figures included artisan Natalla Charytonava-Kryževič, bibliographers Ksienija Suša and Iryna Pahadajeva. Artisan Natalla Kremis was also convicted under the same article (361-4 of the Criminal Code), but the details of her case remain unknown to rights defenders.

Natalla Charytonava-Kryževič and Ksienija Suša were detained during a January 2024 raid by security forces targeting people who provided food aid packages to political prisoners and their families as part of the social initiative INeedHelpBY (KGB declared it an “extremist formation” on January 23, 2024). Ksienija Suša was sentenced to 3 years in a penal colony under Articles 361 (calls for actions aimed at harming the national security of the Republic of Belarus) and 361-4 of the Criminal Code. Natalla Charytonava-Kryževič received 5 years in home confinement under two parts of Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code. Bibliographer Iryna Pahadajeva was detained in May for helping political prisoners. A court sentenced her to 3 years in a penal colony for 32 money transfers totalling 188 BYN (~57 USD) she wired to a pre-trial detention centre. She later walked out free under a pardon.

Illustrator Natalla Levaja, detained upon returning from Poland, was sentenced to six years in a penal colony and fined 40,000 BYN (~12,000 USD) for donations totalling approximately 1,275 euros made in 2021–2022, including to the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment [18]. Earlier, Natalla had voluntarily paid to the state an amount equivalent to the donations she made in 2020 to the funds assisting victims of repression. She had received a written confirmation from the KGB about the payment.

Ksienija Chodyrava, a cum laude cultural studies graduate of the Belarus State University, was sentenced to 5 years in a penal colony for donations. The details of her case remain unknown.

Special risks for women prisoners

Female cultural figures persecuted for political reasons in Belarus face the following risks when behind bars:

- In temporary detention facilities, the staff is predominantly male, there is no privacy, and video surveillance is conducted.

- Sanitary areas are not isolated, and hygiene products are either not provided or are issued in insufficient quantities. Showers are allowed once a week.

- There are no conditions for drying clothes.

- Women are forced to carry heavy bags, clean up large areas, and perform other physically demanding work.

- Prolonged exposure to such living and working conditions undermines health: weakened immunity, deterioration of chronic diseases, disrupted menstrual cycles, infections and reproductive system issues.

- Dozens of women from the cultural sector spend months and years behind bars, facing these hardships.

Additionally, in the summer of 2024, reports emerged that the administration of the women’s colony in Homiel introduced a new rule prohibiting the transfer of hygiene products, including sanitary pads, in food parcels. They can only be received twice a year with a clothing package. Prisoners do not always have the funds to purchase hygiene products in prison stores.

In 2024, an investigation titled “Torture and Abuse Women’s Penal Colony No.4, Homel” was published, detailing living conditions in the units, slave labour at the sewing factory, forms of punishment, and persecution of political prisoners in the colony.

PERSECUTION OF EXILED FIGURES

Transnational persecution of cultural figures was a growing trend in 2024.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION

Throughout 2024, information continued to emerge about cultural figures becoming targets of criminal cases, individually and as part of cases initiated against groups. Criminal prosecution affected at least 40 cultural figures among political emigrants.

In connection with publications in a column on Radio Svaboda, the General Prosecutor’s Office opened a criminal case against writer and journalist Siarhiej Dubaviec, accusing him, among other things, of “denying the genocide of the Belarusian people”. It also became known about the initiation of criminal proceedings against poet and blogger Valer Rusielik, writer Hanna Złatkoŭskaja (her dacha was seized), poet, writer, and journalist Alaksiej Dzikavicki (his grandfather’s country house was seized), activist Alaksiej Kuźmič, artist Vijaleta Viarbickaja, and other cultural figures persecuted for their views.

Additionally, in 2024, several criminal cases were initiated against groups that included cultural community representatives.

On 20 March, the Investigative Committee announced that a criminal case was opened against representatives of People’s Embassies (“Belarusians Abroad”), claiming it possessed information on over 100 representatives of “radical diasporas”. (On February 28, 2024, the KGB declared this project of Belarusian diaspora “extremist formation”).

On 16 May, news surfaced about a criminal case in Belarus against the participants in the Freedom Day celebrations held in full compliance with local laws in the cities with active Belarusian diasporas. Belarus’ Investigative Committee said it treated 104 individuals as suspects in the “Belarusians Abroad” case. PEN Belarus expressed protest against persecution for celebrating the national Belarusian holiday.

On 21 May, it became known that the Investigative Committee launched a criminal case against 257 people running for the Coordination Council, cultural community representatives among them.

SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS AND IN ABSENTIA SENTENCES

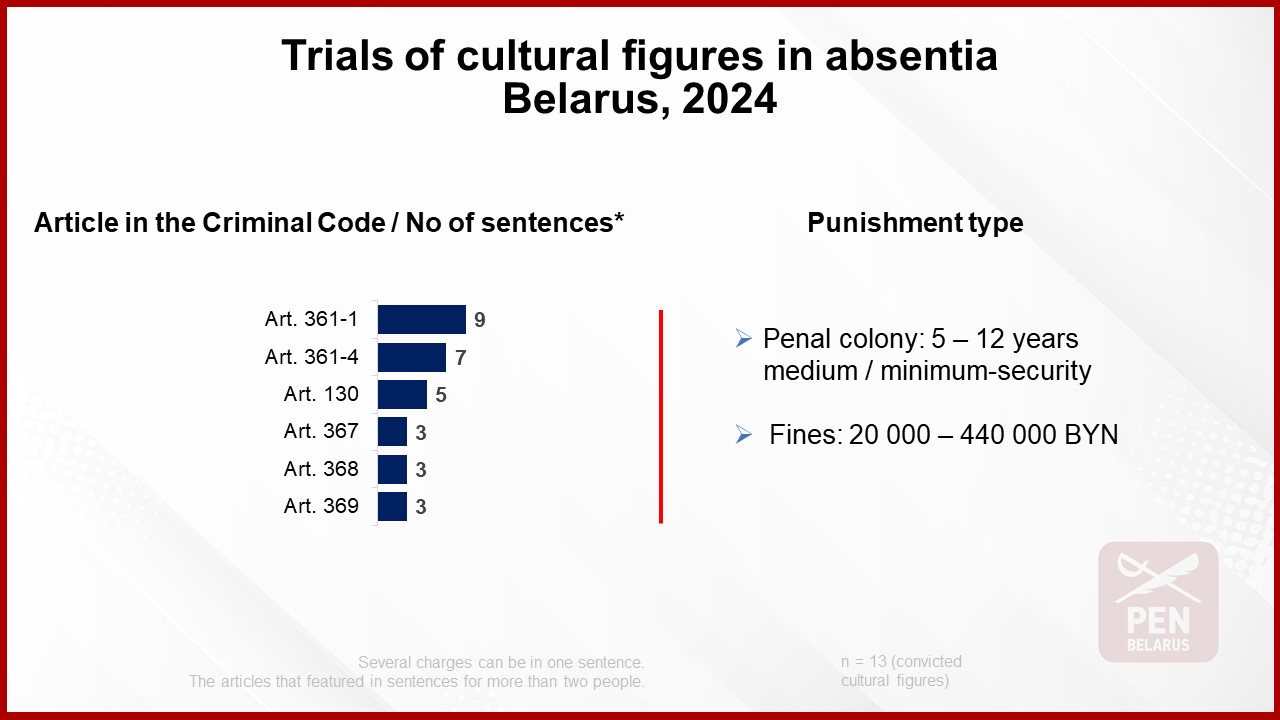

The special proceedings practice is a repressive tool used in Belarus against political emigrants to silence them. This procedure contradicts constitutional guarantees of a fair trial, violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and completely strips the prosecuted of the right to defence.

In 2024, this procedure was initiated against at least 20 cultural figures, with producer Alaksandr Čachoŭski targeted twice. 13 cultural figures were convicted in absentia, with their assets seized. Among them: philosopher and director of the Institute for Strategic Studies Piotr Rudkoŭski, writer and political commentator Jury Drakachrust, political scientist and translator Alaksandr Łahviniec, publicist, founder and chairman of the International Congress of Belarusian Researchers organising committee, political scientist Andrej Kazakievič.

These individuals were part of the “Sviatłana Cichanoŭskaja’s Analysts” case associated with the Telegram channel “Analityki ST” (Sviatłana Cichanoŭskaja’s Analysts) designated as an “extremist formation” one year before the special proceedings began. They were sentenced to 10–11 years in prison and heavy fines in absentia. According to the case materials, the accused allegedly prepared theses for Sviatłana Cichanoŭskaja’s public speeches. They posted publications on “destructive resources” aimed at intensifying protest sentiments, deepening divisions in Belarusian society, and increasing political and economic pressure on the Republic of Belarus. A total of 20 Belarusian experts were convicted in absentia in this case and included in the lists of “extremists” and “terrorists”.

For participating in the activities of the YouTube channel “Rudabelskaja Pakazucha” (designated as an “extremist formation” by the Ministry of Internal Affairs on 17 May 2023) and several other charges, a trial in absentia was held for songwriter, blogger, and activist Andrej Pavuk, opera singer Marharyta Laŭčuk, rock musician Uładzisłaŭ Navažyłaŭ, and producer Alaksandr Čachoŭski.

- Andrej Pavuk was sentenced to 12 years in prison and a fine of 200,000 BYN (~59,000 USD).

- Marharyta Laŭčuk and Uładzisłaŭ Navažyłaŭ received 6 to 8 years in a penal colony and fines ranging from 20,000 to 32,000 BYN.

- Alaksandr Čachoŭski was tried in absentia twice. The first time, he was accused of insulting a government official and desecrating the state symbols. In his public video address, Čachoŭski mentioned that he did not even know what he was charged with. He was sentenced to 3 months of arrest at that time, but the case was later sent for reconsideration. In the second trial, he was accused of “extremist activities” and received 7 years in a penal colony and a fine of 32,000 BYN.

In 2024, other in absentia convictions included:

- Writer, historian, and human rights defender Uładzimir Chilmanovič (5 years in a penal colony and a 40,000 BYN fine);

- Architect Vadzim Dzmitranok (12 years in a penal colony and a 440,000 BYN fine);

- Prison literature author Alaksandr Kirkievič (7 years in a penal colony and a 24,000 BYN fine);

- Standup comedian Słava Kamisaranka (6 years in a penal colony);

- Psychologist and writer Volha Vialička (9 years in a penal colony and a 12,000 BYN fine).

The sentence against Volha Vialička became the first known case of punishment under Article 193-1 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (Illegal organisation of the activities of a public association, religious organisation, or foundation, or participation in their activities), which was reinstated in the Criminal Code in January 2022. In Belarus, Volha Vialička was the head of the charitable organisation “Hrodna Children’s Hospice”, which the authorities forcibly liquidated in August 2021.

In absentia sentences: general trends

The most common charges against exiled cultural figures were related to alleged “extremist activities“ (Articles 361-1 and 361-4 of the Criminal Code). Inciting hatred (Article 130 of the Criminal Code) and insulting representatives of the authorities, including Alaksandr Łukašenka (Articles 367–369 of the Criminal Code), featured as the second most frequent charges.

OTHER FORMS OF PERSECUTION, INCLUDING UNDER THE GUISE OF COMBATING EXTREMISM

Authorities continued to carry out raids at the places of registration of exiled cultural figures and exerted pressure on their relatives inside Belarus. Parents were periodically visited for inspections, detained and punished in administrative proceedings, threatened, and forced to call their children and ask them to return to Belarus, etc. State-owned media continue defamation and discrediting campaigns. The social media accounts of cultural figures and their projects are labelled as “extremist materials”, and organisations are designated as “extremist formations”.

In 2024, the following were recognised as “extremist materials“:

- Instagram page of PEN Belarus;

- Instagram page of the Resource Centre of the Belarusian Council for Culture;

- Websites of the Reformation news portal, which pays considerable attention to cultural issues: reform.by and https://reformby.org;

- Website of the Polish community Znadniemna.pl (until recently, the portal of the Union of Poles in Belarus);

- Telegram channel of the Belarusian Institute of Public History;

- Telegram channel “sekktor | opportunities for cultural and creative people of Belarus”;

- Facebook fan page of the independent Belarusian film festival Bulbamovie;

- Telegram channel supporting Belarusian cultural figures in Warsaw, “Dom Tvorcaŭ”;

- Telegram channel of the initiative of people “who love to sing together” – “Śpieŭny Schod”;

- Facebook and Twitter pages of the “cultural movement that emerged in August 2020” – “Volny Chor”;

- Website and several social media pages of the “portal about Belarus and Belarusians” – “Budźma Belarusami!”;

- YouTube channel and song “10 million slaves” by the Daj Darohu! Band;

- “The Song of a Cheerful Belarusian” by Arsien Kislak (AP$ENT);

- Music video by Alaksandr Bal based on the poem “My Homeland is in Trouble”;

- TikTok account “Fundacja Tutaka”;

- Social media accounts, as well as the logo and email address of the theatre troupe “Kupalaŭcy”;

- Social media pages of artists and activists, including Uładzisłaŭ Bochan, musician Timote Suladze, artist Volha Jakuboŭskaja, opera singer Marharyta Laŭčuk, musician and journalist Kaciaryna Pytleva, comedian Michail Iljin, poet and translator Andrej Chadanovič, musician Jury Stylski, film scriptwriter and director Andrej Kurejčyk, designer Uładzimir Cesler, artist Anton Radzivonaŭ, art critic Mikita Monič, music critic Alaksandr Čarnucha, singer and theatre director Svieta Bień, comedian Słava Kamisaranka, actress Kryscina Drobyš, musician Uładzisłaŭ Navažyłaŭ, and many others.

The following were designated as “extremist formations“:

“Volny Belaruski Universitet” (Free Belarusian University); Internet resources: Belarusian Radio Racyja, “Heta Minsk, Dzietka” (This is Minsk, Baby), DW Belarus – that also have sections focusing on Belarusian culture, Znadniemna.pl – the former portal of the Union of Poles in Belarus, continuing to cover topics and events relevant to the Polish community; communities of Belarusians abroad: People’s Embassies of Belarus, ABA Together (Association of Belarusians in America) – these organisations have the mission to preserve Belarusian heritage, culture, and language; an online store of products with national symbols: “Admietnaść” (Uniqueness); an independent theatre troupe: “Volnyja Kupałaŭcy” (Free Kupała Theatre Actors).

THREAT OF EXTRADITION AT THE REQUEST OF BELARUSIAN AUTHORITIES

One of the threats to cultural figures in exile is the risk of extradition at the request of Belarusian authorities. For instance, film director and activist Andrej Hniot was arrested at the airport upon arrival in Belgrade (Serbia) on 30 October 2023, based on an arrest warrant requested by the Belarusian Interpol bureau. He was accused of tax evasion (Part 2, Article 243 of the Republic of Belarus Criminal Code). Hniot and his lawyers stated that the charges were fabricated and politically motivated, asserting that the prosecution was an act of revenge for his activism (the Free Association of Athletes SOS-BY initiative).

Hniot spent more than seven months in a Serbian prison. Serbia’s Supreme Court twice issued rulings to extradite the film director, and on 6 June 2024, he was placed under house arrest. On 13 September 2024, the Serbian Court of Appeal ruled to return the case to a lower court for reconsideration due to insufficient evidence for extradition.

On 19 September 2024, the European Parliament mentioned Andrej Hniot in its Resolution on the Severe Situation of Political Prisoners in Belarus. On 31 October 2024, the film director was evacuated from Serbia. On the same day, it became known that the Baranavičy District and City Court on 29 October 2024 had added his Instagram account to the list of extremist materials.

ACTS OF VANDALISM AND HATE SPEECH AGAINST THE BELARUSIAN DIASPORA IN VILNIUS

In 2024, a series of vandalism acts targeted Belarusian organisations in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, affecting several cultural sites. In most cases, offensive inscriptions in Lithuanian were left and windows broken:

- On 28 July, the Belarusian souvenirs store Kropka was attacked by unknown individuals, with windows broken and offensive graffiti against Belarusians left on the building’s façade.

- On 1 August, an offensive inscription addressed to Sviatłana Cichanoŭskaja appeared on the European Humanities University (EHU) building, where Belarusians constitute the ethnic majority of students.

- On 4 September, unknown individuals shot at the windows of the premises, where the Belarusian Orthodox community belonging to the Patriarchate of Constantinople holds services and broke the windows of the Belarusian House (Belarusian Community and Culture Centre in Vilnius.)

- On 5 September, another derogatory graffiti against Belarusians appeared near the office of the Belarusian volunteer organisation Dapamoha (Help).

- On 26 October, unknown individuals set fire to the entrance doors of the Belarusian Community and Culture Centre in Vilnius, left offensive graffiti, and defaced a local mural.

- On 5 November, xenophobic inscriptions appeared on the Belarusian café Karchma 1863 building.

As of writing, the instigators and perpetrators of these acts of vandalism targeting Belarusians in Lithuania have not been identified. However, there are serious grounds to view these incidents not as random occurrences but as provocations by Belarusian security services and deliberate actions by the Łukašenka regime.

PEN Belarus issued a statement, calling on the Lithuanian authorities to conduct a thorough investigation of these incidents and appealing to the international community and human rights organisations to pay attention to these attempts to incite hostility between Belarusians and Lithuanians artificially.

DISMISSALS, A BAN ON PROFESSION AND THE PRACTICE OF VOUCHING

According to Culture Minister Anatol Markievič, who spoke at an off-site meeting of the Presidium of the Council of the Republic at the end of March 2024, the authorities have learned lessons from the events of 2020, and “the ranks of the creative intelligentsia are being cleansed of those who undermined the foundations of the state”. At the ceremonial event on 11 October dedicated to Cultural Workers’ Day, he noted successes, stating that the cultural community had been purged of “destructive elements”.

Throughout the year, new evidence of the termination of labour relationships with employees in the cultural sector continued to emerge. The reasons for the dismissals (non-renewal of contracts) included the latest lists of “unreliable” individuals, denunciations by colleagues or “concerned” citizens, subsequent security checks, recent administrative punishment on political grounds, and other formal or less obvious reasons.

In 2024, there were 49 documented cases of violations of the right to work affecting 48 cultural sector employees, including 46 cases of politically motivated dismissals of ideologically “unreliable” employees (one specialist was dismissed from two jobs simultaneously) and 3 cases of refusal to hire for low-skilled work (a janitor, a security guard, and a kindergarten nanny). Most dismissed are respected specialists and laureates of numerous awards, including state prizes. Specialists who have come under repression effectively lose the opportunity to earn a living as ideologists and HR security specialists embedded within state institutions do not even allow them to take on low-skilled positions.

The most significant number of dismissals during the analysed period affected the fields of theatre, museology, and the film industry.

At least four theatre directors were dismissed in 2024, including:

- Tacciana Čajeŭskaja (Minsk Regional Puppet Theatre “Batlejka”) – under the pretext of “inefficiency”.

- Siarhiej Pukita (Belarusian State Academic Musical Theatre) – after the touring Voronezh Symphony Orchestra performed Viktor Tsoi’s song “Changes!” [19].

- Dzmitry Harelik [20] (Homiel State Theatre, he had headed it since 1992) – in January 2024, he was subjected to administrative punishment for “disseminating extremist materials”.

- Sviatłana Karukina (Theatre of Belarusian Drama) – for “insufficient ideological commitment”.

Also fired were:

- Viktar Klimčuk, the artistic director of the Belarusian Theatre “Lalka” (Puppet) (for “failure to meet the planned targets”). He had worked at the theatre since 1990.

- Maksim Brahiniec, Arciom Kurań, Hanna Siemianiaka and Dzmitry Davidovič – the leading actors of the Theatre of Belarusian Drama.

- Other theatre professionals.

In the Brasłaŭ Museum of Traditional Culture, the dismissal of seven employees – including the museum director, Eleanora Zinkievič and the People’s Master of the Republic of Belarus, Valer Zinkievič – was preceded by their detention and administrative persecution in December 2023.

In 2024, the film studio “Belarusfilm” “parted ways” with animator Alaksandr Lenkin, who had worked there for 40 years, and with the leading specialist of the animation studio, Valancina Nikifarava. The following people were dismissed from the documentary film studio “Letapis”:

- Aksana Ejchart, director;

- Halina Adamovič, a documentary film director. She had worked at the studio since 1995;

- Uładzimir Maroz, film director and writer. He began his career in Belarusian cinema in the early 1980s.

There have also been reports of dismissals at the Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts (especially among specialists in the preservation of intangible cultural heritage), the Minsk College named after A.K. Hlebaŭ, the Brest Musical College named after R. Šyrma, the Academy of Arts, the Youth Theatre, the Faculty of Philology at BSU, and several other cultural institutions.

Dismissals and the intimidation of employees, preventive talks with the “unreliable” about the inadmissibility of “extremism”, ideological re-education, monitoring of social media, coercion into joining trade unions, excessive bureaucratisation, censorship, and total control characterise the current situation in state institutions. The system is experiencing an acute shortage of personnel: “Some have been dismissed, some left on their own, some were imprisoned, some left the country” (©) [21]. One of the means of the system’s survival lies in the practice of vouching. According to cultural figures who have retained their positions in state institutions, there are two lists of disloyal individuals: those on the first list are not allowed to work in state-owned structures at all; those on the second list may work if a guarantor can vouch for them. This practice means that an “unreliable” employee can work in an institution at the director’s personal responsibility. Every cultural institution now has lists of such employees.

PRESSURE ON ORGANISATIONS AND COMMUNITIES IN THE CULTURAL SPHERE

85 cases of administrative interference (including forced liquidation) in the activities of state, private, or non-governmental organisations related to the cultural sector in Belarus were documented.

A BAN ON ACTIVITY (“PURGES” IN THE STATE REGISTRY)

In late May and early June, a series of arrests took place involving the professional masters of the ceremony as well as the directors of agencies listed in the state registry of organisers of cultural and entertainment events. The trigger for the arrests was the “revealing” posts by pro-Russian and pro-government activist Volha Bondarava on her Telegram channel “Bondareva. BEZ KUPYUR”. She accused several cultural managers of attempting a state coup in her posts. She demanded that the Ministry of Culture carry out a “purge” of the registry of organisers of cultural and entertainment events.

On 27 May, it became known that the founder of the event agency Grafimil, Siarhiej Sarokin, and his wife (we don’t know the name), a dance instructor, were detained. On 28 May, the AP Event CEO, Andrej Papłaŭski, was detained. On 30 May, the Event Café CEO, Jury Kapucki, and his co-founder Rusłan Daniłkovič, were arrested. On 31 May, Most Event host Viktar Stelmach and the master of ceremonies for festive events, Pavieł Paškievič (later prosecuted under Article 342 of the Criminal Code), were apprehended. On 5 June, Aleh Astralenka, the deputy director of the Pink Zebra event agency, was detained.

Following the arrests and the publication of “repentance videos” featuring representatives of the event agencies, the Ministry of Culture began removing organisations from the registry. On 5 June, the registry had six fewer organisations: the mark “excluded” appeared next to Event Cafe, Pink Zebra, Grafimil, Svietomuzyka By, AP Event, and Most Event. In mid-June, two more agencies – Zoykina Kvartira and PhoenixArt – were removed from the registry. Thus, the agencies that had completed all registration procedures momentarily lost their status.

Project Event and “Upravleniye Sobytiyami” (Events Management) also disappeared from the registry in August. By the end of the year, the “Registry of Organisers of Cultural and Entertainment Events” contained 46 active organisations out of 59 (13 had been excluded).

CLOSURE OF EDUCATIONAL CENTERS AND LANGUAGE SCHOOLS

On 5 January, the Polish language studio PanProfesor announced its closure, reporting that security services had visited one of the company’s employees in Minsk at the end of December 2023 and searched the company’s office. “As it later turned out, on the morning of 21 December, PanProfesor was not the only one to experience this. Several other companies that ran Polish language courses saw their CEOs, employees, and teachers detained, with some forced to record ‘repentance videos.’ In addition to the already known charges, the accusation of ‘teaching Polish’ was added”, the studio’s message stated.

Faced with a persistent recommendation to cease operations and voluntarily liquidate the company, PanProfesor was forced to close. “We made the decision that, as painful as it is, the only possible course of action in this situation is to close the Belarusian company”, representatives of the studio said. It later became known that PanProfesor could continue its work in a modified format (on a Poland-based online learning platform).

In October, it became known that the Department of Financial Investigations visited the office of one of Belarus’s most prominent language schools – Streamline, founded in Minsk in 1998, with branches nationwide and a staff of approximately 300 teachers. During the inspection, a search was conducted, servers were disconnected, and accounts were blocked. A liquidation procedure was initiated against the school’s legal entity, the Educational Center “Obrazovatel’nye tehnologii” (Educational Technologies). According to a centre representative, there were no legal grounds for this. The school received no official notification of liquidation, and the proper procedures were not followed. Since 17 October, the network of language schools has been in a state of liquidation. As of early February 2025, access to the organisation’s website – str.by – has been blocked.

A criminal case was launched against the Streamline founders, Eduard Celuk and Anastassia Toŭscik, along with other centre leaders, on large-scale tax evasion charges (Part 3, Article 243 of the Criminal Code). The Investigative Committee claims the school failed to pay no less than 17 million BYN in taxes. An arrest was imposed on the assets of the individuals involved, including the houses and land plots, worth over 9 million BYN.

At the end of October, it became known that the educational centre Lider, in operation since 1999 and present in 27 cities across Belarus, had suspended its activities. The reasons for the language courses’ termination are still unknown. The centre’s social media channels have not been updated since 2 September 2024.

In November it became known that AKC Most foreign language school had ceased operations in Brest, whose office was sealed on 13th. The company was founded in 2006 and specialised in Polish language classes.

FORCED LIQUIDATION OF NON-PROFIT ORGANISATIONS

In 2024, at least 39 organisations operating in the cultural sphere were forcibly liquidated. Among them were 15 associations registered in Belarus as early as the 1990s. Various sectors were affected:

- theatre – the Family Inclusive Theatre Foundation and the Belarusian Centre of the International Puppeteers’ Union (UNIMA) were closed;

- literature and language – the Literary and Artistic Foundation “Nioman” (the publisher of the Dzejasłoŭ magazine; its final – 127th – issue came out in December 2023); the Belarusian Republican Public Association of German Language Teachers, and the Educational Centre for Training, Professional Development, and Retraining of Personnel “Educational Technologies” (Streamline language courses) were shut down;

- visual arts – the operation of the Public Association “International Guild of Artists” and the International Public Association of Artists and Art Historians “Master” was terminated;

- history and culture of remembrance – the Belarusian Association of Victims of Political Repression, the Historical Society “Trascianiec”, the Assembly of the Heirs of the Nobility, the Youth Public Association “Historica”, the international public association “Knights of Outremer”, and the Belarusian public association “Victory Foundation – 1945” were closed;

- national minorities – the Georgian Cultural and Educational Society “Mamuli”, the Public Organization of Belarusian-Turkmen Friendship “Dostluk”, the Tatar association “Zikr ul-Kitab”, the “Kislev” Cultural and Educational Charitable Foundation, the International Public Organization “Yemeni Community”, and the Public Association “Belarusian Federation of Kazakh Kures” were liquidated;

- architecture – the Belarusian Academic Centre MAAM and the Belarusian Public Association of Architects and Construction Science Workers were liquidated;

- other associations.

It is important to note that 4 March 2024 was the deadline for bringing the charters of public associations into compliance with the new requirements of the Law “On Public Changes” (adopted on 14 February 2023). Primarily affected were national and international organisations. After the deadline expired, the registering authorities began a campaign to liquidate associations that had not updated their charters per new provisions, which nonetheless does not negate the repressive nature of the legislation.

As Lawtrend noted, the liquidation process did not follow a uniform pattern. Some public associations received warnings and urgent demands to submit documents, while lawsuits for liquidation were filed against others immediately, without additional notifications.

INTERFERENCE IN THE OPERATION OF CREATIVE UNIONS

Systemic pressure on creative associations continues in Belarus. Government bodies interfere in the activities of communities of photographers, designers, and artists, using expulsion from unions as a tool of manipulation.

Officials have taken control of creative associations, forcing them to “normalise”. To continue working and maintaining state-leased studios, unions must make compromises. On 28 February, the Ministry of Culture’s Telegram channel reported about a working meeting between the minister and the heads of the Artists’ Union and the Designers’ Union. During the meeting, the ministry set targets for the year and issued directives. However, genuine instructions are given behind closed doors and out of the public eye. Like many state institutions, creative unions are supervised by KGB “curators”.

It is known that in 2024, the expulsion of “unreliable” creators from unions continued. Many were made to sign a “repentance letter”. Those who participated in protest exhibitions or expressed a civic stance in their creative work were forced to write statements that they were quitting the unions “voluntarily”.

By creating administrative hurdles for some associations, the state supports loyal structures. One such organisation is Belarus’s pro-government Writers’ Union, which celebrated its 90th anniversary in 2024. The Union openly demonstrates loyalty to Alaksandr Lukašenka’s policies, actively collaborates with Russian counterparts, and supports a pro-Russian development vector.

Meanwhile, the independent Union of Writers was forcibly liquidated on 1 October 2021; the largest publishing houses lost their licenses. However, the public association Writers’ Union of Belarus continues to receive state funding. 613,792 Belarusian BYN (around 180,000 USD) were allocated in 2024. Support is set to continue, with 695,483 BYN allocated for 2025.

OTHER FORMS OF PRESSURE ON ORGANISATIONS

Temporary suspension of licenses and bans on selling printed publications, refusal of distribution, suspension of private centres’ activities, inspections of venues and “recommendations” not to hold events, interference in programming and censorship, visits by security services, revocation of leases, mass purges, blocked websites, designation as “extremist formations”, and the annulment of domain names – such as Baj.by, Reform.by, and Symbal.by – are just the tip of the iceberg of the pressure exerted.

CENSORSHIP AND OTHER VIOLATIONS OF CULTURAL RIGHTS

Systematic restrictions on freedom of expression, access to information, and culture continue in Belarus. Historical events in museums can only be presented according to official guidelines. Festivals, competitions, and conferences are subject to censorship, with individuals possessing “inconvenient” opinions barred from participation. Independent online resources are blocked without warning or explanation on orders from the Ministry of Information. At the same time, state-sponsored events proceed strictly in line with pre-approved scripts, excluding anyone not on the list of invitees and disallowing alternative viewpoints.

The persecution of the Belarusian-language and historical literature remains a separate form of repression. Prohibited publications are removed from libraries and stores, with booksellers facing threats of administrative and criminal proceedings. “Undesirable” books in penal colonies are burned, and the discovery of such literature during a search of a citizen’s home can lead not only to accusations of distributing “extremist materials” but also to the use of physical force against them.

The 2024 monitoring recorded 133 cases of censorship: the cancellation or suspension of approved exhibitions, plays, film screenings, and concerts of individual performers or groups; the removal from exhibitions of works by specific authors or thematic blocks; the denial of touring permits; the banning of festivals; refusal to allow participation in competitions, conferences, and congresses; the deletion of references in academic papers to avoid mentioning authorship; the Ministry of Information’s prohibition on distributing an entire list of literature, and other examples.

CANCELLATION OF CULTURAL EVENTS AND REFUSAL OF PERFORMANCES

The main reasons authors or their works were not allowed to reach the public remain the same: persecution related to the 2020 events and the lists of “unreliable” cultural figures. “Literally a week before the event, I got a call saying that my performance was cancelled ‘for technical reasons’ – that’s it. Later, as a friendly aside, they told me: ‘It’s because of your experience in 2020, your political experience” (©).

In addition, officials have censored topics related to Belarusian national history, as well as so-called propaganda of the “wrong values” – in particular, LGBT themes, sexuality, Western culture (Halloween, Santa Claus, quadrobics, etc.), and the works of Ukrainian and Polish culture.

The year 2024 began with high-profile instances of censorship affecting the exhibitions: the Insomnia painting by Uładzimir Kandrusievič in the Theatre of Belarusian Drama, Vasil Bykaŭ. The Life Through Shapes and Lines in the State Museum of the Belarusian Literature History, 1.10 Squares in the Palace of Arts in Minsk; the play Clara Was Here in Belarusian State Youth Theatre; screening of the films Fairy Tale and Sun by Alexander Sokurov and A Russian Boy by Alexander Zolotukhin in the Falcon Club Cinema Boutique. More details on these and other instances of censorship are described in the January – March 2024 report.

In recent years, it has become a tradition that after the opening of the Art-Minsk exhibition, several paintings are taken down (even though the list of authors and works passed preliminary censorship). Thus, after the launch of Art-Minsk 2024 on 3 May, the works by artists who had condemned the violence against peaceful protesters in 2020 were removed. Overall, Art-Minsk serves as an indicator of what is happening in the field of visual arts. Remarkably, there has been a significant drop in participants, primarily due to the ever-growing “ban list” of artists. In 2024, the festival featured 200 authors, whereas Art-Minsk 2020 showcased “more than 400 Belarusian and foreign artists”. It is also known that, post facto, some works were removed from the Viva Kola Art 2024 exhibition, which took place in the same Palace of Arts in the autumn.

In Homiel, the organisers did not receive permission to hold the 8th FreeTime-Fest cosplay festival – “Apart from the increasingly complicated procedure for registering a social and cultural event, it feels like creative events of our kind are not in favour” (last year, Ministry of Culture did not approve the festival either). In Polack, the Kampai cosplay festival did not take place – according to the new director of the House of Culture, where a “children’s performance 12+” was supposed to be held, anime promotes “improper values”. The program of Manhattan Short in Belarus’s annual international short film festival was shortened. Between 26 September and 6 October, nine of the ten participating films were shown, as censors did not allow the Ukrainian film Mama, which portrays the start of the war in Ukraine.

Pro-government activists and propagandists, referred to as “people’s experts”, continue to wield significant influence on cultural events in Belarus. One can single out the cancellations of events prompted by denunciations from Volha Bondarava in Hrodna. Her appeals to the Ministry of Culture and other executive bodies – demanding attention to particular events (or cultural figures) – often produce results. For instance, she succeeded in cancelling the 7th Karani (Roots) ethno-festival (16-18 August), the LITARA JA exhibition by artist Antanina Falej (starting 27 August at the Arts Gallery salon-store), and in revoking touring permits for concerts by Russian performers Mzlff (Ilya Mazelov) and Alena Shvets (which were to be held at the Re:Public club on 21 April and 18 May, respectively), as well as for the bands Psikheya (21 September at the Reactor club in Minsk) and Melnitsa (7 December at Minsk’s Prime Hall). The touring permit for the Dziady concert (3 November at the Reactor club) was revoked; the Dobry viečar dobrym ludziam (Good Evening to Good People) exhibition by Aleś Suša (1 December at the Janka Kupała State Literature Museum) did not open. Several other cultural events were also cancelled.