Foreword: The voices of cultural workers from Belarus

Introduction

Self-censorship and creativity

Self-censorship and repressions

Self-censorship as a way of preserving Belarusian culture

Conclusion

FOREWORD: THE VOICES OF CULTURAL WORKERS FROM BELARUS [1]

We live as if we are inside the books we read in childhood about guerillas and underground resistance fighters […] People live like partisans; they keep a low profile. Some were not jailed, and there were those whom authorities threatened to jail. The rest tried to stay quiet until they were discovered […] Being in Belarus, we follow some information safety rules: don’t share some posts, don’t write posts on serious topics – light self-censorship, or maybe not so light […] We don’t post [potentially dangerous] links […] My French friend, an artist, says: “I see that my publication was viewed, but there are no likes – what happened?” – Look, our <…> was arrested for three days for liking a post on the Nexta [2] channel three years before […] Now we use more private chats with our colleagues, we discuss mainly ordinary things […] People try to keep everything to themselves and reduce talk to a minimum even with their family members, relatives and friends: “I don’t work, I didn’t have my contract renewed” – that’s it […] I tend not to maintain active ties because ties with me can compromise for someone [3] […] Everyone keeps a low profile […] Everything has stood still at the grassroots level, with less publicity […] There are fewer public discussions; people keep everything to themselves […] They try to keep exposure of their names or activities to a minimum […] Communication is only word-of-mouth via recommendation. The events are not for everyone, but only for those you know well […] Many cultural figures deliberately do not show up because, all the same, you must live in Belarus […] You don’t want to get exposed, even if you do some non-political events like a butterflies’ exhibition – you just don’t want your name mentioned anywhere. A safety threat […] But I’m afraid. I observe safety hygiene […] People who want to work here know their limits; they know what can be shown and what shouldn’t […] Deep down, people have self-censorship, which controls them […] This inner censor does not allow people to do anything; even if there is no external threat today, they either leave the country to avoid this pressure or hide and do nothing in the public space. Otherwise, one can only draw cats and flowers, but people with critical thinking cannot be satisfied with this, and it is not enough for them […] Self-censorship has reached the point when they [librarians] would flip through books themselves: if they thought something was wrong with a book, they would remove it from the shelves without waiting to be added to the list [4]. However, it might not end up on the list at all… This edition [Sviatłana Aleksijevič’s 5-volume book published by Łohvinaŭ in 2018] looks defiant in white-red-white colours, so it is safer to put it aside, away from the open collection […] We engaged in self-censorship when we checked the social media accounts of stage directors before sending their names to the Ministry of Culture for approval […] All the time you hear that this or that name should not be mentioned in the state-owned media. Still, now it is self-censorship that does the job. In most cases, employees do not name such people [disloyal to the regime] […] Everyone goes underground […] The longer it lasts away, the more cautious people become […] We are getting deeper and deeper […] Many people who stay in Belarus now work under pseudonyms – it doesn’t matter whether in Belarus or Europe […] People want to participate; they are ready to travel and show some of their projects, but they are not prepared to expose their names even in Europe because it is clear: a European media publishing their name means the game is over […] It’s called a ‘violation of the right to a name’ when people are forced to operate under pseudonyms: they participate in some projects but don’t reveal their names […] Mimicry is what is going on now. I think this is how self-censorship and fear are manifested; it haunts people and artists in the first place […]

INTRODUCTION

Self-censorship, or inner censorship, is the conscious limitation of self-expression, where a person refrains from openly expressing thoughts, ideas, etc. The reasons for this can vary: psychological, economic, legal, ethical, and others.

On the one hand, it is a necessary tool in professional activity – concerning reputation and respect, responsibility, adherence to specific standards, and maintaining a balance between freedom of expression and the boundaries accepted in society. On the other hand, self-censorship may not stem from personal choice but rather be a forced adaptation, a response to direct external threats – this type of self-censorship will be discussed here.

In the context of political repression, which Belarus has been experiencing for over four years, inner censorship has become a response to changed circumstances, a survival mechanism, and even a reflex. People resort to it out of fear of losing their jobs, threats to personal safety, persecution of family members, and other reasons. Self-censorship has become part of daily life, restricting free expression of thought and creativity and hindering the development and advancement of Belarusian culture and art. Inner censorship is an invisible, non-public form of repression that is challenging to monitor and measure. Understanding its scale and consequences, exploring ways to study and document it, and examining its impact on cultural figures’ self-esteem and moral state are essential for public awareness and solidarity and a foundation for further reflection and analysis.

This document describes the methods of forced self-restraint employed by cultural figures who have come under the monitoring of the Belarusian PEN group and directly from writers, musicians, and artists. It also touches on the topic of self-censorship in the dilemma of “publicising versus silence” concerning facts of repression.

Incidentally, this text itself is, in essence, an example of self-censorship, as it omits several names, titles, and events.

SELF-CENSORSHIP AND CREATIVITY

PEN Belarus monitors noted for the first time the trend of self-censorship and anonymity in creativity due to repressions in the monitoring report tracking violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural workers in the third quarter of 2021. By that time [late September], there were 715 political prisoners in Belarus, including over 60 cultural figures convicted, among other things, for their creative work. According to police investigators, the musicians of the Irdorath band [5] “used bagpipes to reinforce the protest mood”; artist Aleś Puškin [6] was sentenced to five years in a penal colony for a portrait of an anti-Soviet underground resistance activist. Mass dismissals of artists disloyal to the regime were in full swing. The “ban lists” of artists had returned. Searches, interrogations, arbitrary detentions, and administrative and criminal prosecution continued, including cases associated with public statements or comments on socio-political events in social media. The campaign to forcibly liquidate non-profit sector organisations was gaining momentum, and pressure on the Polish minority, independent book publishers, art venues and international cultural cooperation organisations, shops with goods bearing national symbols continued. The products of independent culture – books, songs and articles – were methodically added to the List of Extremist Materials.

Self-censorship in creativity was the result of this socio-political situation. Some examples from 2021:

- When printing a book <…>, a publisher <…> refused to include several poems in which the author described her attitude to the civil and political crisis in Belarus.

- The band members <…> decided not to publish a protest song <…> because they feared persecution by the authorities.

- A stage director <…> reported that he was forced to remove the video of a performance from the theatre’s YouTube channel for the sake of the safety of the actors who remained in Minsk.

- The organisers <…> decided not to mention the name of the Prize’s patroness <…> at the award ceremony.

- <…> refused to participate in the Orša Battle annual festival of bardic songs due to insecurity.

- When the regime treated any gathering of people as an “unauthorised mass event”, an organiser of The Night of Executed Poets, a memorial event to commemorate the literary figures repressed in 1937, proposed to hold readings in an online format.

- The Watch Docs human rights documentary film festival’s team decided to postpone the online film festival scheduled for 13–19 April.

- The organisers of the Pradmova Intellectual Book Festival decided not to hold the event that year.

- More examples are available.

In 2022, the trend of “internal emigration” expanded and consolidated. There were 1,446 political prisoners at the end of the year, at least 108 cultural workers among them. That was the time when a register of organisers of cultural and entertainment events was set up; art managers were under pressure, requirements for tour guides were toughened, pro-government activists carried out “cleansing cultural visits” to bookstores and art exhibitions looking for “wrong” literature or unreliable authors. Such institutionalised repression and persecution accelerated the mass exodus of cultural figures from the public space. With the beginning of the so-called “special military operation”, public support for Ukraine became another topic for self-censorship.

Due to the potential threat of prosecution for creative expression, there are more and more cases when cultural figures suspend activity in the public domain and cancel their projects partially or entirely. Events are increasingly organised underground or transferred to the online format, repertoires are revised, and groups change their names for “encryption.” Fearing accusations of “extremism”, publishers intensify self-censorship and withdraw books noticed by pro-government activists and propagandists. Tour guides and museum workers are forced to mind their narratives (e.g., in light of the new “genocide of the Belarusian people” concept). Librarians grow increasingly cautious when it comes to the procurement of new books. Artists tend to remove some of their works from exhibitions to be on the safe side. Political filtration of creativity is noted among stage directors, art managers, and other participants in the cultural process. The use of pseudonyms and anonymity of authorship for books, articles and reportages, documentaries, songs, exhibitions, expertise, comments for the media, participation in events, etc., is gaining momentum.

Self-censorship examples from 2022:

- The musicians of the Mister X band, whose frontman is former political prisoner Ihar Bancer, decided “not to play with fire” and refused a live presentation of their new vinyl record.

- Euroradio closed its popular rubric “You Have Not Heard This ” (over 150 episodes were broadcast and published over four years). The broadcaster explained its decision, among other things, by the danger of cooperating with an “extremist formation” for musicians from inside Belarus.

- The new book <…> summarises the history of Belarus’ nation-building and independence. The last illustration is inscribed as “The Coat of Arms and Flag of the Republic of Belarus, established in 1991,” but it does not have an image.

- Because of repressions against book publishers, only 3 applications were received to participate in the Carlos Sherman Prize (awarded for the best translation of a fiction book into Belarusian), while the usual number would be 15-20.

- The organisers of the HLIADAČ video creativity festival moved it from offline in Minsk to YouTube, where it was held on 23–24 September.

- After the war in Ukraine started, a dance ensemble <…> removed the Ukrainian performance from the programme, showcasing the dances of the world’s peoples.

- More examples are available.

Gradually, self-censorship became an integral part of the everyday life of Belarusian cultural workers regardless of their location. Inside the country, it concerns topics related to the attitude towards the current authorities, decisions of officials, and statements on burning socio-political issues. Everything connected with Belarusian nation-building and history (the Belarusian People’s Republic, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the nobility, etc.), its state figures and moral authorities (Tadevuš Kasciuška, Kastuś Kalinoŭski, Łarysa Hienijuš, Vasil Bykaŭ, etc.), historical symbols (the white-red-white flag, the coat of arms “Pahonia”), the use of the Belarusian language in everyday communication became unsafe. The topics associated with gender and LGBTQ+ are self-censored. The expression of the anti-war stance and support for Ukraine in the war with Russia, the promotion of Ukrainian and Polish culture and educational products are concealed. The ties with political prisoners, human rights activists, cooperation with cultural figures from the “ban lists”, media and organisations designated as “extremists” by the regime, political emigrants, etc., are “encrypted.”

Examples 2023–2024:

- “In public places, you will think twice before replying in Belarusian or saying “dziakuj” [thank you], let alone switching fully to Belarusian.”

- A translator <…> asked not to be named as the website contains political statements.

- An author <…> withdrew his photos from Alhierd Bacharevič’s new book so as not to be exposed together with Bacharevič and Januškievič (publisher).

- “A workday does not start with a morning coffee; it starts with the “Please, call” message on the phone. I called and was told: “Bondarava [7] wrote about <…> It is better to remove this book from the website to be on the safe side.” I removed it, wrote emails to colleagues, and continued my daily work routine.”

- “One needs to remove the mention that you are also a human rights defender.“

- “The topic of the event <…> [an authorised concert in a Minsk music club] is such that it’s scary to attend. You can get into trouble […] They could have everyone arrested during the concert.

- Prison parcels, a photograph of the wife in a red blouse with a white pattern – “If they find something like this on a prisoner, he will end up in a punitive cell.“

- For the main character’s safety, the filmmakers <…> asked independent media not to write about the premiere.

- The web portal <…> covering art unpublished the 2022 interview with the political prisoner’s sister <…> for security reasons, as the website’s author is in Belarus.

- On Mother Language Day, the United Transitional Cabinet [8] awarded Francysk Skaryna Medals for the contribution to the preservation and popularisation of the Belarusian language to Vincuk Viačorka, Uładzimir Niaklajeŭ, Elżbieta Smułkowa, Ivonka Surviła, Siarhiej Šupa and four other people, whose names were not disclosed for security reasons.

- An author <…> writes under a pseudonym for security reasons. The book’s editor, illustrator and translator are also anonymous.

- On 5 May, the Free Belarus Museum venue hosted a theatre performance <…> in Warsaw. The author remained anonymous since the playwright was in Belarus.

- The printing house laid down conditions: “You need to remove the poems on the following pages: …”

- More examples are available.

Despite the relative freedom of creative people outside Belarus, there is also self-censorship among them. Fearing possible pressure on family members back home and considering the practice of criminal prosecution in absentia, which has gained momentum since 2023 [9], many exiled cultural figures refuse interviews, avoid public statements and try not to be associated with “extremist” authors, organisations or platforms (and not necessarily designated as such). They hide their faces, avoid being photographed and mentioned, refuse to participate in events or agree to attend them only on condition of anonymity, ask not to be tagged in social networks, not to be mentioned in posters, etc.

Since publicity has become unsafe, pseudonyms are in use again. Forced anonymity of authorship has become characteristic of the present Belarusian culture, and often even outside the country. Many famous and novice poets, artists, playwrights, translators, musicians, designers, organisers of cultural events, sound engineers, photographers, editors, experts, and journalists conceal their names and faces.

The trend of growing anonymity of authorship (as well as the process of moving a cultural product outside Belarus) can be traced to the example of the Michał Aniempadystaŭ Prize. Founded in 2019 in memory of the artist, poet, photographer, designer, publicist, and cultural critic Michał Aniempadystaŭ, the award is handed out for the best cover for a Belarusian book. The jury evaluates the design, printing quality, and alignment with the content.

The complete list of the 2020 Prize included 37 books; the names of all the nominated authors were known, and the winner was ceremoniously announced at the Pradmova festival in Minsk.

In 2021, the full list had 28 books, and all names were public, but the award ceremony was streamed online on YouTube.

The complete list for the 2022 Prize included 32 books, with all the nominees’ names known. That was the first year the award took place in exile, and the ceremony was held in the Polish town of Bielsk Podlask.

Due to various circumstances, the Prize did not take place in 2023.

In 2024, the Michał Aniempadystaŭ Prize was awarded twice: in May – for the best book cover of 2022 and in October – for 2023. During the award ceremony for the best book cover of 2022, the chairwoman of PEN Belarus, Tacciana Niadbaj, noted: “The times dictate their own rules, and the award is evolving to remain accessible to all participants in the literary process: both those who remain in Belarus and those who had to leave. For example, the opportunity to participate in the award anonymously has been introduced.”

In 2024, 14 covers were nominated for the 2022 award, two of which were by anonymous authors: Alhierd Bacharavič’s Vieršy [Poems] and Julija Cimafiejeva’s Voŭčyja jahady [Wolfberries].

For the 2023 award, the full list included 37 books, of which 11 covers were by anonymous authors. Those covers were for the books Biełaruski narodny sonnik [Belarusian Folk Dreambook] by Alina Vysockaja, White Shroud by Antanas Škėma, The Great Gatsby by Francis S. Fitzgerald, Kruhlaia Square [Round Square] by Val Klement, Mesopotamia by Serhiy Zhadan, Pieratrus u muzei [A Police Search in the Museum] and Płošča Peramohi [Victory Square] by Alhierd Bacharevič, the books by Wisława Szymborska, Adam Mickiewicz, and Maria Kuncewicz for the Polish Classics for the Belarusian Reader series, Conversations with Friends by Sally Rooney, Čas pustaziella [The Time of Weeds] by Hanna Jankuta, and The Black Obelisk by Erich M. Remarque. Nearly one in three covers (30 %) were anonymous.

SELF-CENSORSHIP AND REPRESSIONS

Among the trends that emerged by 2021, alongside self-censorship, forced emigration for personal safety, and several others, there was a noted tendency for cultural figures not to publicise instances of pressure exerted on them – a form of self-censorship regarding repression. Today, at least 10 % of the information monitored regarding violations in the cultural sphere consists of confidential facts about dismissals, administrative detentions, interrogations, censorship, and more.

The opportunities for human rights activists and independent media have also become more restricted. Numerous instances of administrative and criminal prosecution of cultural figures have stopped reaching the public domain or become known only after some time (this is one reason for the post-factum recognition of political prisoners). Human rights defenders regularly request reports of persecution to obtain an objective picture of repression.

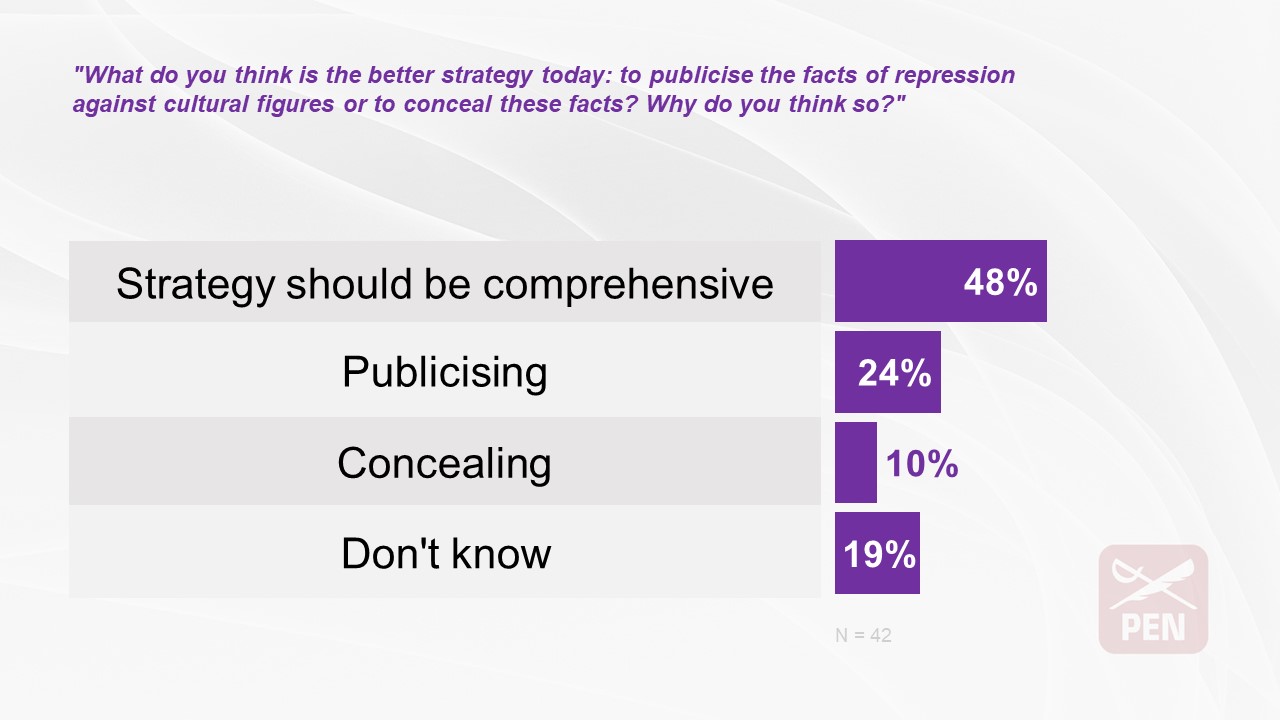

In 2023, during a series of interviews with 42 creative individuals living and working in Belarus, one of the questions was: “What do you think is the better strategy today: to publicise the facts of repression against cultural figures or to conceal these facts? Why do you think so?” The arguments expressed at that time remain relevant today. Here is the distribution of responses:

Almost every second respondent (48 %) believed that the strategy should be comprehensive – this group will be described in more detail below.

Nearly one in four respondents (24 %) considered publicising instances of persecution the correct strategy. It is important to note that among those who responded were individuals both directly unaffected and those who had experienced repression. Here are some of the arguments expressed:

- people should know what is happening; they need to know to draw conclusions and understand the scope of events: “Sometimes, someone leaves the country, and people think they just left, but later it turns out they were detained”;

- one of the regime’s goals is to silence everyone as if nothing is happening while publicising reminds people that what is happening is unlawful; any crime occurs when no one knows about it. Silence can be seen as complicity: “If we have this tool – media and public platforms – we should use it. It scares certain representatives because it is powerful and significant”;

- publicising increases the likelihood of more cautious treatment of the repressed, as when someone is not spoken about, anything can be done to them: “Widespread publicising helps the repressive apparatus understand that attention is being paid to this person and that they are valuable to a community. Publicising helped me in my case”;

- it offers the opportunity to support the persecuted, as when there is awareness about such people, they can receive support: “Letters and other forms of support become possible”;

- some respondents stated that if detained, they would want their detention to be made public, regardless of their relatives’ opinions.

On the other hand, 10 % of respondents – one in ten cultural figures – supported the strategy of concealing repressions. Their arguments included:

- avoiding drawing attention to the individual, as publicity could worsen their situation or harm them: it might make finding future employment impossible; “If you start talking about it, you might end up right back where you just escaped from, and very quickly.” It could also worsen treatment in prison: “We must remain silent and not publicise details about their condition in prison, as it could affect their … I can’t say comfort, nor any good treatment, but at least prevent wild torture”;

- publicising could also lead to pressure on not just the individual but their family and loved ones;

- premature disclosure might spread misinformation, cause panic, or harm: “Because a person can be held for 10 days without trial, charges, and explanation“;

- some mentioned that being labelled a victim or “enemy of the people” could be distressing for the person and lead to malicious delight from others.

Thus, the arguments for publicising repression include informing society, resisting the strategy of silence, and protecting and supporting victims. Those who choose the strategy of silence fear that publicity could worsen the situation, harm individuals, endanger their families, and jeopardise careers and futures; they want to avoid victim status.

The most frequent response, as mentioned earlier, was that the strategy should be comprehensive and tailored to each specific case: “situational,” “a differentiated approach is needed,” “it depends on where the person is located,” “it must be a comprehensive strategy,” “we need to find an approach that protects those in this situation, but it cannot be ignored,” “perhaps this is only possible with the person’s consent,” “there are situations where publicising can greatly harm a person, irreparably harm them, and in such cases, it absolutely must not be publicised. But some situations need to be shouted about at the top of one’s lungs,” “it is always a dilemma… quite a dilemma.“

When discussing the publicising of repression, respondents particularly emphasised the increased responsibility for words and adherence to journalistic ethics:

- one must be careful with statements, avoid thoughtless dissemination of information, write only what is known, and refrain from hypothetical or loosely interpreted statements: “Often, the person has no idea, and even those who detained them may not know. So, we should not assist in this regard”;

- whenever possible, publish names only with the victim’s permission;

- exercise caution in cultural journalism: “There should be a general rule now that all events are not automatically for media coverage. In cultural matters, it is essential first to agree with event organisers on whether they want coverage, what they want written about them, and ultimately fact-check the material before publication.”

Regardless of the strategies adopted by cultural figures, everyone unanimously agreed on the importance of collecting information, as documenting these facts helps maintain a comprehensive understanding of what is happening and its high cost. That is not only a way to record the horrors of our time for future generations but also a tool that will allow people years later to understand why culture evolved in its current state to restore an objective history. The absence of reliable information over time distorts the picture.

SELF-CENSORSHIP AS A WAY OF PRESERVING BELARUSIAN CULTURE

As we have considered it so far, self-censorship is a mechanism of self-protection for cultural figures, a means of survival in response to the potential threat of persecution for their creativity. At the same time, it represents a period of silence, of non-disclosure, as a conscious choice, a way to preserve Belarusian culture for its next revival: “to preserve oneself, to hide in the swamp, and then resurface.” Independent Belarusian culture has chosen creative underground methods: it has shifted to the mode of apartment performances and private gatherings, underground and word-of-mouth communication, closed and intimate formats, allegorical language and veiling, self-isolation and internal emigration, working in isolation and accumulating creative output. This way, silence becomes a way to continue honestly doing one’s work: “The fewer red flags, the more real opportunities to do something and develop Belarusian culture.”

Under new conditions, many creators do not stop; they find strategies and ways to express themselves, use the possibilities of the internet, participate in conferences and discussions, and maintain connections with those who have left the country. “They are dismissed or leave their official jobs, but they do not abandon what their life is dedicated to. It’s their essence, their soul. A person cannot escape it. People cannot act differently, so they continue to do what they are doing. Maybe they just talk about it less because…”; “People strive to live and do something, and for them to only hear negativity – that this place is a desert, that it’s already ‘Khatyn’ – of course, that irritates them.”

To claim that nothing is happening in Belarus today because of the repression, that everyone has gone underground, is incorrect. In reality, various creative actions are taking place within the country. And it is crucial to document them, although this is extremely difficult:

“…There is a challenge in this documentation itself: on the one hand, you want an event happening here to be recorded, reflected somewhere, because life exists here, and people remain here, and those people are doing something. On the other hand, you start joking about how this will be reflected, how compressed, incomplete, or conveyed through hints it will be. And thirdly, where will this be published (if it will be at all), on what resources: blocked resources, ‘extremist’ resources – that is, who will access this information? That is such a compression: we see the full picture – this is 100 %, but in the end, when the reader reaches it, they will see only 60 % of what happened. And this is a very real dilemma.”

CONCLUSION

In the context of a deep socio-political crisis, the institutionalisation of repression, and the penetration of censorship into all spheres of public life and culture, self-censorship has become one of the key realities of cultural life in Belarus. It is a forced survival tool for many creative individuals, but at the same time, it is a factor that undermines cultural development, critical thinking, and diversity. Self-censorship is reshaping the landscape of Belarusian culture, confining it within the narrow boundaries of anonymity and isolation.

Today, when freedom of creative expression is perceived as a challenge to the state, and every word or gesture can be interpreted as a threat to the regime, the cultural community needs solidarity and support more than ever. International and domestic assistance mechanisms – from providing platforms for anonymous self-expression to ensuring the safety of creative individuals – must become part of a strategy to preserve and support Belarusian culture. It is crucial to protect those who remain, assist those forced to emigrate, and document every story and every work created during these harsh times.

Belarusian culture today is, on the one hand, a culture of resistance and preservation and, on the other, a culture of enforced silence and anonymity. The urgent task for the future is to restore the integrity of the cultural landscape, free creativity from censorship and self-censorship, and return to all creators – who, despite severe threats and constant pressure, continued to create – their voices and right to a name.

[1] Excerpts from a series of interviews (42 in total) conducted with Belarusian cultural figures in spring 2023.

[2] One of the most popular opposition Belarusian media channels.

[3] Former employee of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, dismissed after 15 days of administrative arrest.

[4] “List of Extremist Materials”.

[5] In December 2021, five of the band’s musicians were sentenced to 1.5-2 years in a penal colony.

[6] Aleś Puškin died in prison on 11 July 2023 due to untimely medical care.

[7] Pro-government activist.

[8] The UTC is a structure of the Belarusian democratic movement.

[9] In 2022, amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code of the Republic of Belarus were adopted to allow for the prosecution of political emigrants in absentia.