This material has been prepared based on summarised information collected by the Belarusian PEN monitoring group from open sources, personal contacts, and direct communication with cultural figures. The data reflect the situation as of the time of writing and may be updated as new information becomes available.

Despite efforts to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the data, some gaps may remain, including in the identification or classification of individuals as cultural figures, due to the limited availability of public information. PEN Belarus welcomes any clarifications or additional information readers may wish to share. To report a violation (including confidentially) or to correct data presented in the report, please contact us at [email protected] or t.me/viadoma.

Given the situation in the cultural sector in Belarus, the role of cultural figures in public life, and the importance of artistic activity for safeguarding and developing cultural rights, PEN Belarus recognises them as defenders of cultural rights in line with the approach outlined in the report A/HRC/43/50 of the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights (2020). More information about the monitoring is available here.

Note: For reasons of information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources that are subject to restrictions under the legislation of the Republic of Belarus.

Main results

Pardon and forced deportation of cultural figures from Belarus

Arbitrary detentions and criminal prosecution

Conditions of detention and violations of cultural rights in places of imprisonment

Designation of cultural initiatives, their social media, and products as “extremist”

Censorship and other violations of cultural rights

State policy in the sphere of culture: Resolution No. 454 “On the Register of Organisers of Cultural and Entertainment Events”

Conclusion

MAIN RESULTS

From January to September 2025, repression for dissent and the expression of opinion continued in Belarus, including arbitrary detentions and arrests, and politically motivated administrative and criminal prosecution of cultural figures both inside the country and abroad. Censorship and the cancellation of cultural events persisted, as well as the forced liquidation of public organisations. The lists of so-called “extremists” were further expanded with new names, initiatives, and materials. The list of printed publications allegedly “harming the national interests of the country” was supplemented with new books.

Among the key developments of the third quarter were: the pardon and deportation to Lithuania on 11 September of 52 [1] people, including 40 political prisoners – eleven of whom were representatives of the cultural sphere: Uładzimir Mackievič, Pavieł Mažejka, Zmicier Daškievič, Mikoła Dziadok, Pavieł Vinahradaŭ, Łarysa Ščyrakova, Jaŭhien Mierkis, Alaksandr Mancevič, Alaksiej Silenka, Hleb Hładkoŭski, and Siarhiej Sparyš. Other notable events include the continued complete isolation of political prisoner, lawyer, writer, and bard Maksim Znak for more than two and a half years; new criminal cases against music teachers for participating in the 2020 peaceful protests; detentions of organisers of cultural and entertainment events, including those loyal to the regime; and the cancellation of the premiere of the play Sisters Grimm at the State Puppet Theatre in Minsk.

The sell-off of assets confiscated from imprisoned philanthropist and businessman Viktar Babaryka also continued, with 19 paintings from his private collection put up for auction. Cultural figures in exile faced persecution as well – notably, threats to the life of former Minister of Culture Pavieł Łatuška.

The authorities designated the punk band Dzieciuki and the jewellery brand Belaruskicry as “extremist formations”. They labelled as “extremist materials” two books by Belarusian philosopher Valancin Akudovič and fantasy adventure stories for teenagers by Valery Hapiejeŭ, as well as the online library Kamunikat.org. The list of printed publications whose distribution is deemed potentially harmful to the country’s national interests was expanded with two books by Saša Filipienka (Sasha Filipenko) and the poetry collection Here They Are, and Here We Are: Belarusian Poetry and Poems of Solidarity – a compilation of contemporary Belarusian poems and texts written in solidarity with the protest movement of August 2020.

Among the key directions of state policy were the entry into force of Resolution No. 454 of the Council of Ministers “On the Register of Organisers of Cultural and Entertainment Events”, further tightening state control and regulation in the field of culture and public initiatives; a cooperation agreement between the Ministry of Information and the Belarusian Orthodox Church aimed at countering publications “coming from abroad”; the establishment of a Parliamentary Assembly Commission on the preservation and protection of “correct” historical memory; and an agreement between the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation on cooperation in the field of intellectual property, among other measures.

Repression in figures (January – September 2025):

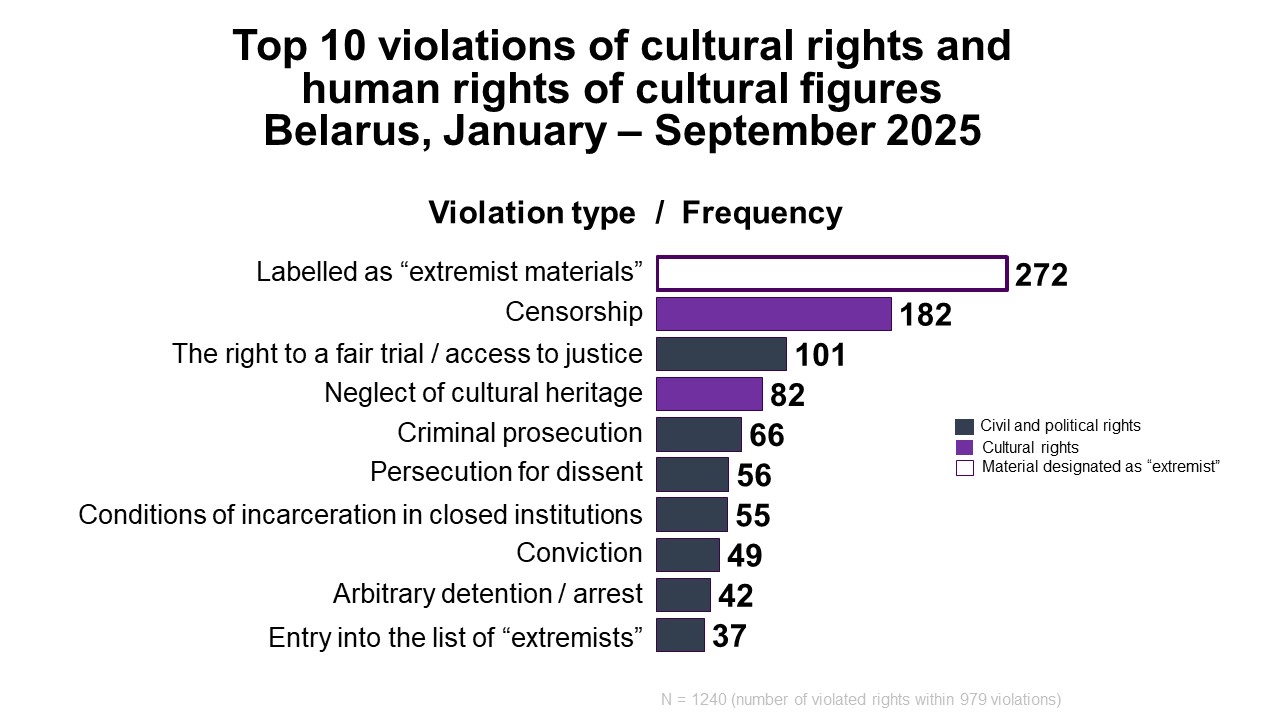

- A total of 979 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures were recorded.

- As of 30 September 2025, there were 1,197 political prisoners [2] in Belarus, including at least 94 representatives of the cultural sector.

- At least 151 cultural figures are serving sentences in places of incarceration (penal colonies, prisons, pre-trial detention centres) or in open-type facilities and home confinement. [3]

- The designation of cultural materials and social media accounts of cultural figures as “extremist materials” remains the most frequent violation recorded in the monitoring (272 cases). Censorship, including the list of printed publications “banned for distribution in Belarus”, ranks second (182 cases). Violations of the right to a fair trial and access to justice occupy the third place (101 cases).

- Top 10 types of violated rights:

- Criminal cases were initiated against 66 cultural figures, with one in three cases concerning the persecution of political emigrants.

- At least 49 cultural figures have been prosecuted, including three tried in absentia.

- At least 40 cultural figures were subjected to arbitrary detentions or arrests, two of them twice.

- Administrative punishment was reported against 19 individuals from the cultural sector (20 offence reports were filed).

- At least 4 former political prisoners – cultural figures who emigrated after receiving sentences of restricted freedom in an open-type facility or in home confinement – were tried in absentia, with their initial sentences replaced by harsher ones.

- An additional 37 cultural figures were included in the list of citizens, foreign nationals, and stateless persons involved in “extremist activities”, and nine more were added to the list of organisations and individuals associated with “terrorist activities”.

- Courts issued rulings on the forced liquidation of 7 culture-related NGOs.

- The Ministry of Information added 31 books (documentary, historical, and fiction literature) to the National List of Extremist Materials.

- The list of printed publications deemed capable of “harming national security” was expanded by 138 new entries.

- 82 cases of improper treatment of cultural heritage sites and memorial places were recorded.

PARDON AND FORCED DEPORTATION OF CULTURAL FIGURES FROM BELARUS

Between January and September 2025, at least 18 cultural figures were released under pardon, 15 of whom were forcibly deported from Belarus.

On 12 February, through the mediation of the US government, poet, translator, and journalist Andrej Kuzniečyk was released from a penal colony and taken to Lithuania together with two other political prisoners.

On 21 June, philologist and Italianist Natalla Dulina, journalist and culture writer Ihar Karniej, and cultural manager and blogger Siarhiej Cichanoŭski were among 14 political prisoners released and deported.

On 11 September, the following were pardoned and taken to Lithuania: philosopher Uładzimir Mackievič, journalist and publisher Pavieł Mažejka, publicist Zmicier Daškievič, writer and blogger Mikoła Dziadok, non-fiction author and blogger Pavieł Vinahradaŭ, documentary filmmaker Łarysa Ščyrakova, journalist and ethnographer Jaŭhien Mierkis, founder and editor of Rehijanalnaja Hazieta Alaksandr Mancevič, architect and musician Alaksiej Silenka, videographer and musician Hleb Hładkoŭski, and activist and musician Siarhiej Sparyš. In total, 52 people were released, including 40 political prisoners.

Some cultural figures had only a few weeks or months remaining on their sentences. In an interview with independent media, Natalla Dulina said that “being expelled from the country was the worst thing that could have happened”, since she had only a few months left before she could decide freely whether to stay or leave Belarus.

The released political prisoners were not informed about their destination until they were brought to the Belarus–Lithuania border, where they were handed over to US diplomats – effectively deported without official release documents. 13 people, including several cultural figures, were transferred to Lithuania without passports, the primary identity document. Human rights defenders are now analysing the legal implications of the Belarusian authorities’ actions in depriving citizens of their passports. This has created serious obstacles to their legalisation abroad.

Philosopher Uładzimir Mackievič said that his manuscripts written in prison were confiscated before his deportation.

“When it became clear that they were taking us abroad, I experienced two excruciating moments: first, I was being forcibly removed from my own country. And second, that all my writings were taken from me. There were moments when inspiration struck, and I believe some of those notebooks contained the best philosophical reflections I have ever written. Sadly, they are all gone. That is my greatest pain”.

Mikoła Dziadok, Ihar Karniej, and others also reported that their letters and manuscripts – weighing up to 20 kilograms in some cases – were confiscated upon their release.

Despite this wave of pardons, one cannot say that repression in Belarus, including against the cultural sector, has decreased. At least 30 new cultural figures were recognised as political prisoners during the same period.

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS AND CRIMINAL PROSECUTION

Between January and September 2025, at least 40 arbitrary detentions and arrests of cultural figures were recorded (two people were detained twice). Events from the first half of the year, including the arrests of several administrators of the Belarusian-language Wikipedia section, were detailed in the previous monitoring report.

In the third quarter, additional information surfaced about several arrests that had taken place earlier in 2025 within the so-called “Hajun case” – targeting individuals accused of sending information to the Belaruski Hajun monitoring project’s chatbot, which tracked the movement of Russian troops and military equipment across Belarus. In February, security forces gained access to the project’s user data, triggering a wave of detentions of those suspected of transmitting information. Among those persecuted were historian and ethnographer Alaksiej Drupaŭ, founder of the art village “Čyrvony Kastryčnik” Kirył Kraŭcoŭ, and local historian and archivist of the Kličaŭ Regional Museum Jaŭhien Staravojtaŭ. According to reports, within the same case, musician and cultural manager Anatol Volski and historian and tour guide Anton Arciuch were also detained. All five were charged under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code (“facilitating extremist activity”), with Staravojtaŭ, Volski, and Arciuch already convicted.

In September, former political prisoner, journalist, and local historian Alaksandr Lubiančuk was detained again. He had only been released from a penal colony in January 2025, after serving a three-year sentence on charges of “creating or participating in an extremist formation” (Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code) for his cooperation with Belsat TV. Lubiančuk was reportedly detained again under a new criminal case – likely also connected to the “Hajun case”.

***

During the third quarter of 2025, a series of arrests in the concert industry occurred following the designation of the Telegram chat “Org BY” as an “extremist formation” (see also this section). According to Naša Niva, the chat was discovered on the phone of a concert organiser, after which security officers tracked down and detained other participants identified within Belarus. In some cases, additional charges were brought, including allegations of corruption. Reportedly detained were:

- Illa Piatroŭski, director of Blackout Studio,

- Alaksandr Manyšaŭ, associated with Atom Entertainment and Unbreakable agencies,

- The management of Kvitki.by the country’s largest ticketing operator (as of this report, LLC “Kvitki Bel” is reportedly liquidated).

Among those mentioned were organisers of pro-government events and supporters of the Łukašenka regime. It remains to be seen whether more details will emerge about the detainees, the nature of their prosecution, and whether their persecution carries a political dimension.

***

Trials and convicted cultural figures

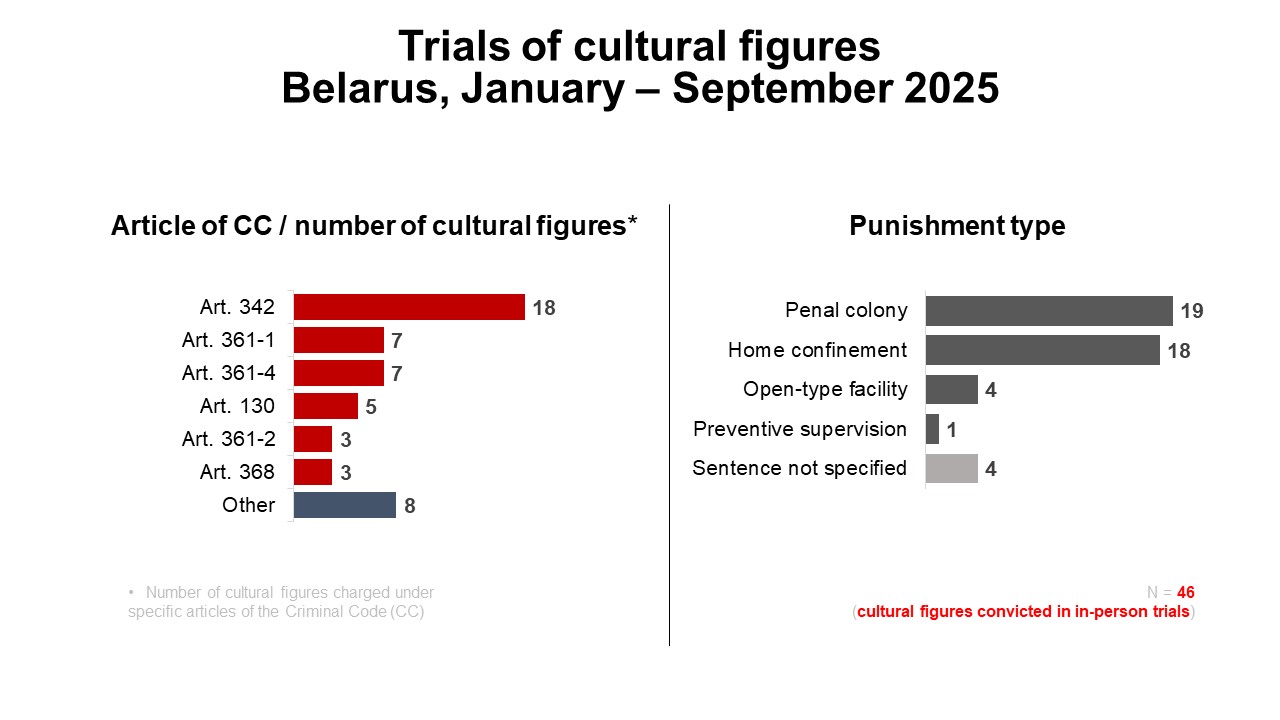

Throughout the reporting period, criminal trials involving prominent cultural figures were held in Belarus every month. Whereas 24 people had been convicted in the first half of the year, by the end of September, this number had doubled to 49, including three convictions in absentia.

Among those sentenced were several music teachers: Vieranika Janoŭskaja, jazz singer and head of the “ArtVocal” studio; Maryna Rapaviec, vocal teacher and head of the “Pretty Band” ensemble; Lilija Pažaryckaja and Alaksandr Pažarycki, accordion teachers. All four are laureates of international and national festivals and recipients of numerous state awards, yet their names have been added to the list of “extremists”. They were sentenced to “home confinement” for participating in peaceful protests in 2020.

On 23 August, the Minsk City Court sentenced renowned artists and a married couple, Ihar Rymašeŭski and Ludmiła Ščamialova, to one year and two months in prison. They were released on 25 August upon completion of their sentence, having spent time in pre-trial detention since October 2024. Rymašeŭski was charged with “inciting hatred” (Article 130 of the Criminal Code) and “threatening a judge” (Article 389 of the Criminal Code). Ščamialova was charged with “organising actions that disrupt public order” (Article 342 of the Criminal Code). Their arrest followed a search during which one of Ludmiła’s paintings – found in another person’s place – caught the attention of security officers. Both artists have long participated in national and international exhibitions, and their works are held in museums, galleries, and private collections in Belarus and abroad.

On 16 September 2025, the Minsk City Court concluded the trial of journalist and writer Ihar Iljaš, which had begun on 21 February. He was sentenced to four years in a penal colony and fined approximately USD 1,380. Iljaš – the husband of imprisoned journalist and author Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvałava) – was found guilty of “discrediting the Republic of Belarus” (Article 369-1) and “facilitating extremist activity” (Article 361-4). The charges were based on his interviews and commentary for independent media outlets, including those in Ukraine. A trained philosopher, Iljaš is also the co-author of the documentary book Belarusian Donbas.

***

Main articles [4] of the Criminal Code used for prosecution (in-person trials):

- Article 342 – organising, preparing or actively participating in actions that grossly violate public order – 18

- Article 361-1 – creating or participating in an extremist formation – 7

- Article 361-4 – facilitating extremist activity – 7 people.

In almost every second case, cultural figures were sentenced to imprisonment in penal colonies – 19 out of 46 individuals received such sentences.

Convicted individuals:

– Julija Łaptanovič, librarian – Article 361-4, sentenced to 2.5 years in a penal colony [5].

– Daniel-Łandsiej Kiejta, choir member – Article 342, sentence not specified.

– Michaił Łabań, craftsman and owner of the jewellery workshop “Samarodak” – Article 361-2, 2.5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type facility [6].

– Alena Badziaka, English teacher – Articles 130 and 361, 2 years in a penal colony.

– Eduard Babaryka, cultural manager and businessman – Article 411, penal colony.

– Kirył Vieviel, musician and screenwriter – Articles 361-1 and 130, 1.5 years in a penal colony.

– Nastassia Achramienka, photographer – Article 367, home confinement.

– Alaksandr Franckievič, writer and anarchist – Article 411, sentence unspecified.

– Anžalika Alasiuk, Belarusian language and literature teacher – Article 368, sentence unspecified.

– Vieranika Žałuboŭskaja, actress, model, and flight attendant – Article 342, 1 year in a penal colony.

– Palina Pitkievič, writer and journalist – Article 361-1, 3 years in a penal colony.

– Viktar Kucharčuk, historian and teacher – Article 130, home confinement.

– Nakanisi Masatosi, Japanese language lecturer – Article 358-1, 7 years in a penal colony.

– Alena Pankratava, writer and journalist – Article 342, home confinement.

– Andrej Niesciarovič, owner of the “Cudoŭnia” ethnoshop – Article 342, 1.5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type facility.

– Nina Bahinskaja, activist and cultural promoter – Article 342-2, preventive supervision.

– Jaŭhien Bojka, cultural activist – Articles 361-1 and 361-3, 5 years in a penal colony.

– Vadzim Pažyviłka, former director of publishing houses for children’s and popular science literature – Article 361-2, home confinement.

– Alena Brazinskaja, English teacher – Article 342, home confinement.

– Siarhiej Sałažencaŭ, IT specialist and dance contest winner – Article 361-2, penal colony.

– Alaksandra Ašurka, founder of Devil Dance Studio – Article 342, home confinement.

– Aleh Zielanko, head of the historical club “Mindoŭh” – Article 361-4, sentence unspecified.

– Pavieł Łaŭrynovič, local historian and religion scholar – Article 342, home confinement.

– Alina Šaŭcova, student at Minsk State Linguistic University – Article 361-1, 3 years in a penal colony.

– Maksim Lepušenka, Belarusian Wikipedia administrator – Article 342, 2.5 years in home confinement.

– Aleh Supruniuk, journalist and local historian – Article 361-1, 3 years in a penal colony.

– Kaciaryna Javid, actress and model – Article 342, home confinement.

– Rusłan Raviaka, writer and journalist – Article 361-4, home confinement.

– Iryna Kiškurna, librarian – Article 361-1, 2 years in a penal colony.

– Ivan Marozaŭ, non-fiction writer – Article 368, 2.5 years in a penal colony.

– Ihar Rymašeŭski, artist – Article 130, 1 year and 2 months in a penal colony.

– Ludmiła Ščamialova, artist – Article 342, 1 year and 2 months in a penal colony.

– Vieranika Janoŭskaja, jazz singer – Article 342, home confinement.

– Maryna Rapaviec, vocal instructor – Article 342, home confinement.

– Volha Nikałajeva, drummer in amateur bands – Articles 361-1 and 342, penal colony.

– Nastassia Trubčyk-Dzivakova, librarian – Article 342, home confinement.

– Michaił Stocik, musician – Article 342, home confinement.

– Lilija Pažaryckaja, accordion teacher – Article 342, home confinement.

– Alaksandr Pažarycki, accordion teacher – Article 342, home confinement.

– Jaŭhien Staravojtaŭ, local historian – Article 361-4, home confinement.

– Ihar Iljaš, journalist and writer – Articles 361-4 and 369-1, 4 years in a penal colony.

– Anatol Volski, musician and cultural manager – Article 361-4, sentence unspecified.

– Anton Arciuch, historian and tour guide – Article 361-4, 3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type facility.

– And three more cultural figures.

Sentences in absentia

Regarding in absentia criminal prosecutions during the first three quarters of 2025:

On 25 September, the Homiel Regional Court sentenced artist Vijaleta Majšuk in absentia to three years in a penal colony. She was found guilty of “creating or participating in an extremist formation” (Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code) and “insulting the President of the Republic of Belarus” (Article 368). In similar “special proceedings”, photographer, cultural manager, and activist Anton Matolka, as well as cultural manager and activist Alaksandr Łapko, were sentenced in absentia to 20 and 16 years in prison, respectively, in addition to fines.

CONDITIONS OF DETENTION AND VIOLATIONS OF CULTURAL RIGHTS IN PLACES OF IMPRISONMENT

Conditions of detention in places of incarceration

Over the past five years, politically motivated persecution has continued even inside places of detention, affecting all cultural figures held there in one way or another.

On 5 August, a court hearing was held to toughen the detention regime of the imprisoned anarchist, writer of prison literature, Alaksandr Franckievič – he was sentenced to three years under a prison regime. The same term was imposed on Vadzim Hulevič, a musician and IT specialist, who was also transferred to a prison regime. Since the beginning of monitoring, at least 18 cultural figures have faced stricter incarceration conditions. For three of them – historian and blogger Eduard Palčys, artist and animator Ivan Vierbicki, and anarchist and prison writer Ihar Alinievič – the terms under the prison regime have now expired.

For more than two and a half years – since February 2023 – there has been no information about imprisoned lawyer, writer, and bard Maksim Znak. He is serving a 10-year sentence in Correctional Colony No. 3 in the settlement of Vićba, where he remains under incommunicado conditions – complete isolation from the outside world. Reports about him, received only occasionally from recently released political prisoners, are extremely rare and outdated.

Despite the opacity of the penitentiary system and the understandable fear of relatives in Belarus to share updates, information continues to surface – primarily from those who have been released from prison.

For example, on 1 February, civic activist Palina Šarenda-Panasiuk, upon her release, reported that in January, publicist and activist Alena Hnaŭk had been placed in a punishment cell for 20 days and received an additional six months in a cell-type confinement unit. Hnaŭk, who is serving her sentence in Correctional Colony No. 24 in Zarečča, suffers from serious health problems but has been denied proper medical care. She has remained in complete isolation for more than a year.

Journalist and editor-in-chief of Rehijanalnaja hazieta Alaksandr Mancevič, pardoned and deported to Lithuania on 11 September, confirmed earlier reports of the deteriorating condition of trade union activist and cultural scholar Vacłaŭ Areška, who has reportedly lost his eyesight in prison:

“During the day, he asks: ‘Is there sun in the sky today?’ The most terrible thing is that at night he must feel his way to the toilet in the dark. He falls, injures himself, and bleeds.”

Prison prose writer Mikoła Dziadok, speaking at a press conference following his release and deportation on 11 September, described the torture endured by many political prisoners:

“Out of nearly five years in prison, I spent a year in solitary confinement. If people from the civilised world saw what those punishment cells look like, they’d think they were back in the Middle Ages. In autumn, in the Hrodna prison, I would wake up at night to the sound of grown men howling and calling for their mothers – that’s how much they suffered from the cold. People went mad before my eyes – literally. I became convinced that a person can be driven insane or to death simply by being left alone in a cell.”

Violations of cultural rights in places of incarceration

This is a separate issue that requires independent and thorough study. Numerous cases of restrictions on political prisoners have been recorded, including:

- Prohibition on attending language courses or studying foreign languages.

- Ban on textbooks and books in foreign languages. In some cases, prisoners were punished by being transferred to solitary confinement for possessing a Polish or Czech language textbook (as reported from Correctional Colony No. 15, Mahiloŭ). In other cases, entire shelves with foreign-language books were removed from prison libraries (Women’s Correctional Colony No. 3, Homiel).

- Ban on borrowing psychology books (Women’s Correctional Colony No. 3, Homiel).

- Confiscation of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago and a general ban on issuing books to persons designated as “extremists” (Correctional Colony No. 17, Škłoŭ).

- Confiscation of manuscripts written in prison, including reports of mass book burnings (Correctional Colony No. 2, Babrujsk).

- Prohibition on participation in cultural activities such as concerts, clubs, or other forms of engagement.

Persecution for the use of the Belarusian language in places of incarceration

Documentary filmmaker Łarysa Ščyrakova, after her release, reported that the prison administration perceived her use of the Belarusian language as an attempt to “provoke” or “set up” the administration.

Local historian and journalist Jaŭhien Mierkis noted that inmates speaking Belarusian were placed on “preventive watch lists” and threatened with solitary confinement.

It is also worth recalling that Vitold Ašurak, a historian and civic activist, and Aleś Puškin, an artist, both of whom died in prison, were subjected to severe pressure, partly because of their use of the Belarusian language.

Persecution for national symbols

There were also multiple cases of persecution for the use of national symbols – for example, prison authorities reportedly demanded that inmates remove tattoos depicting the historical Pahonia coat of arms. Although Pahonia was officially included in Belarus’s list of historical and cultural heritage in 2007, the authorities treat it as an “opposition symbol”.

DESIGNATION OF CULTURAL INITIATIVES, THEIR SOCIAL MEDIA, AND PRODUCTS AS “EXTREMIST”

Under the guise of combating extremism, persecution for cultural activity in Belarus continues. The authorities systematically designate creative organisations and initiatives – especially those working in exile – as “extremist formations”. This entails criminal liability for their members and makes such projects dangerous for people inside the country. Simultaneously or shortly after such decisions, the organisations’ pages and accounts on social media are automatically entered into the “List of Extremist Materials.” From January to September 2025, the following cultural –including educational – initiatives faced such persecution:

- 12 January: the State Security Committee (KGB) declared the Democratic Media Institute’s media hub, established in Lithuania in 2023, an “extremist formation”. Its projects include the Belarusian Content Lab, a competition for independent creators producing media projects related to Belarusian culture and identity. The expert team includes screenwriters, producers, and directors.

- 27 January: The KGB added the crowdfunding platform Gronka, launched in July 2024 to support Belarusian cultural and educational projects, to the list. Among the initiatives it supported were a collection of Belarusian lullabies by EthnoTradition, an audiobook of The Zekameron based on the work by Maksim Znak, and other projects aimed at preserving and popularising Belarusian culture.

- 16 April: The digital educational platform Vasminoh: Education for Belarusian Children Today and Tomorrow was designated as an “extremist formation”. Launched in early 2023, it offers modern interactive courses in the Belarusian language and literature, history and culture, creative writing, and geography.

- 10 July: The Ministry of Internal Affairs designated the Belarusian folk–punk band Dzieciuki – members: Alaksandr Dzianisaŭ, Uładzisłaŭ Biernat, Dzmitry Šmatko, Cimafiej Štaroŭ, Alaksiej Pudzin, and Piotr Dudanovič – as an “extremist formation”. Founded in Hrodna in 2012, the band plays national identity-driven punk [7]; their concerts were repeatedly banned in Belarus. Dzieciuki continue to perform in exile.

- 22 July: The KGB listed the distance-learning platform Belarusian Academy, founded in October 2020 by Sviatłana Kul-Sielvierstava (Doctor of History and poet). It provides European higher education with a Polish university diploma and is the only institution in Poland where instruction is also offered in Belarusian.

- 23 July: The jewellery brand Belaruskicry, created in 2022 by Alaksandra Kurkova (who moved to Georgia after the 2020 protests), was labelled an “extremist formation”. The brand produces jewellery with Belarusian symbols, its best-known item being the “Belarus” pendant with a tear. According to reports, security forces gained access to buyers’ data and threatened each new customer with criminal prosecution. A month after the designation, state TV reported the detention (and aired footage of him in a cage) of Jahor Bužyłaŭ, Belaruskicry’s production director.

- 2 September: The Telegram chat “Org BY” – a coordination forum for concert organisers – was added to the list, with the names Alaksandr Kasinski, Anatol Zapolski-Doŭnar, Vital Broŭka, and Vital Supranovič mentioned. The chat was created in early 2020 to coordinate work during the COVID-19 pandemic as a professional platform for sharing experiences and insights. Activity in the forum stopped in 2021.

20 August 2025: The website ehu.lt and the official Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn and YouTube pages of the European Humanities University (EHU) were declared “extremist materials”. On 15 September, it became known that Prosecutor General Andrej Švied, at the KGB’s request, had filed a request with the Supreme Court to recognise EHU as an extremist organisation and to ban its activity in Belarus as well as the use of its symbols and attributes. The pretext cited was alleged “targeted work to destabilise the socio-political situation in the country”, and the promotion of “alternative” interpretations of historical, cultural and other events, so-called democratic values, and ideas of “Europeanness”. EHU is a private university founded in Minsk in 1992, but it was shut down by the authorities in 2004. Since 2005, it has operated in exile in Vilnius (Lithuania), offering higher education in the arts, humanities and social sciences.

“National List of Extrermist Materials”

In addition to the online resources of the organisations listed above, at least 89 items were added to the list in the third quarter of 2025 alone, and 272 items were added from January to September. Among them:

- Books by Belarusian philosopher Valancin Akudovič (One Must Imagine Sisyphus Happy and The Code of Absence); fantasy novels by Valery Hapiejeŭ ( The Harbinger and Volnery. An Endless Day); and Timothy Snyder’s On Freedom.

- The website and social media of the Belarusian online library Kamunikat.org.

- Three issues of the magazine Belarus and the World.

- The website and logo of Kresy24.pl (on current affairs, culture and history of Poles abroad); the YouTube channel Delfi Lithuania.

- Pages of the ChinChinChannel project by former actors of the Kupała Theatre.

- Social media accounts of Belarusian organisations in Vilnius: the Instagram account of the Svitanak Ethno Centre, the Facebook page of the Centre for the Belarusian Community and Culture, the Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok accounts of the Belarusian souvenir shop Kropka, and the Instagram page of Karčma 1863 in Vilnius.

- The Telegram and Facebook pages of Fundacja Tutaka (promoting Belarusian culture), as well as the website and social media of the Tutaka Fest of Belarusian culture in Podlasie (Instagram and Facebook).

- Instagram and Telegram pages, as well as the logo of ethno.art.by – the School of Traditional Belarusian Culture in Warsaw.

- The Instagram page @belfilmacademy (Belarusian Independent Film Academy) and the Facebook page @BezBuslouArts (independent film company and talent agency).

- The Telegram chat of the community Read – “We Read in Our Native Language!”

- The Facebook account of the band Daj Darohu! and the Instagram page of its online shop; the Facebook page of the band Brutto.

- The Instagram account Belarusian Martyrology (featuring over 1,000 portraits of Belarusian political prisoners by artist Ksiša Anhiełava), as well as accounts showcasing works by artists belarus_art_of_resistance, liht_r, ciesnabrama, sviatlana_painter, leafnaive, and others.

- The Instagram account philosopher_in_prison is dedicated to Uładzimir Mackievič (deleted by the time of this report).

- Other online pages.

CENSORSHIP AND OTHER VIOLATIONS OF CULTURAL RIGHTS

We continue to record cases of artworks removed from exhibitions, bans on publication of “unreliable” authors in state media, refusals to distribute the products of private publishers, personal bans on public appearances, and the denial of permission for independent musicians to hold concerts.

For instance, Vital Artyst, leader of the band Bez Bileta, whose last concert in Minsk took place back in 2019, is forced to appeal to the authorities via a TikTok video, asking them to “approve a concert”. Today, artists find themselves in a situation where they must literally ask for permission to perform.

Bans on cultural events

8 July: The Parason gallery in Minsk cancelled an evening commemorating Belarusian poet Łarysa Hienijuš. The event, at which poet and literary scholar Miсhaś Skobła planned to discuss her life and work, became the target of harsh criticism from pro-government Telegram channels and was ultimately called off.

13 September: At the start of the new theatre season, the Puppet Theatre in Minsk was to premiere the play Sisters Grimm, but one day before the performance, all shows were cancelled “for technical reasons”. The dark comedy by director Jaŭhien Karniah, based on the tales of the Brothers Grimm, failed to pass state review, which deemed it “overly gloomy”. The theatre’s website described the play as “a reflection on love, inner light, and the nature of woman”.

19 September: The concert of the 1990s band Tekhnologiya and the Pleščanicy Fair fest planned in the Łahojsk district were postponed “for technical reasons”. The concert eventually took place on 18 October, but at a different venue.

***

Repression continues to impact all spheres of culture, including the visual arts, music, literature, education, and more. One of the main tools of pressure is the so-called “fight against extremism”: by designating cultural collectives as “extremist formations” (for example, the inclusion of the folk-punk band Dzieciuki in the relevant list), and by adding books, songs, artists’ online pages, and art spaces to the National List of Extremist Materials.

Banned books

Authorities continue to add more titles to the list of printed publications whose distribution may “harm the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”. In 2025 alone, it was updated five times, by an average of 28 books each time. Over the reporting period, 138 titles were added (in fact, 137, as In the Land of Milky Rivers by Siarhiej Vieraskoŭ appeared twice). Among them are:

- Works by Belarusian writer Saša Filipienka (Sasha Filipenka) (The Elephant, The Red Cross),

- Ten books by Scottish author Irvine Welsh (including Trainspotting),

- Five works by Japanese writer and director Ryu Murakami,

- Cult classics by Hunter S. Thompson (Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas) and William Burroughs (Naked Lunch),

- The poetry collection Here They Are, and Here We Are: Belarusian Poetry and Poems of Solidarity, edited by Uładzimir Karkunoŭ, features poems by contemporary Belarusian poets and texts of solidarity written in August 2020 amid the protest movement.

Complete lists of literature deemed “harmful to national interests”, as well as publications entered into the List of Extremist Materials, are available on PEN Belarus’s dedicated website: Belarus. Banned Books.

***

Denials of event approval

Organisers of cultural events typically do not disclose reasons for refusing artists’ participation. However, in today’s cultural climate, artistic selection is only part of the process. The decisive factor is the external vetting of each participant. One documented case showed that in an official response citing Article No. 81 of the Code on Culture of the Republic of Belarus, the refusal to approve an artist’s participation in an exhibition was justified because their activity “poses a threat to national security and public order.”

STATE POLICY IN THE SPHERE OF CULTURE: RESOLUTION No. 454 “ON THE REGISTER OF ORGANISERS OF CULTURAL AND ENTERTAINMENT EVENTS”

In Belarus, state cultural policy continues to develop along the lines of tightened control over the cultural sphere, persecution of dissent, support for regime-loyal figures, the ideologisation and militarisation of the cultural environment, monopolisation of the historical narrative, anti-Western rhetoric, a publicly pro-Russian stance, and pervasive censorship.

A vivid example of this trend is Resolution No. 454 of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus, dated 22 August 2025, “On the Register of Organisers of Cultural and Entertainment Events”, which further expands state control and regulation in the cultural sphere.

Development of the regulation

The road to this resolution took several years:

- In 2022, the updated Code on Culture of the Republic of Belarus laid the groundwork for creating such a register (Resolution 401).

- In 2023, stricter rules were introduced through Resolution 608.

- And in 2025, they were finalised and codified in Resolution 454.

This document did not merely clarify procedures – it turned registration into a permit-based mechanism and significantly strengthened ideological oversight. Some nominal relaxations (for example, removing the requirement that event organisation be a company’s main activity or that the organiser have three years of experience) are primarily technical and serve to simplify the inclusion of state institutions, which must now also be entered into the register.

Key novelties of the resolution

1. Exclusion of individual entrepreneurs and foreign companies

Individual entrepreneurs effectively lost the right to act as organisers back in August 2024, when Resolution No. 457 “On Types of Individual Entrepreneurial Activity” removed event organisation from the list of permitted activities.

2. Mandatory inclusion of state organisations

State institutions must now also be entered in the register. The new wording states:

“The organisation and holding of cultural and entertainment events with the participation of Belarusian and/or foreign performers are permitted only by organisers included in the register.”

Specific state or pro-government entities are exempt – for instance, the rules do not apply to events involving Belarusian performers organised by decision of the President, the Council of Ministers, state agencies, the National State TV and Radio Company, and several other organisations.

3. More complex registration procedure

The permit process now includes additional filters to exclude “undesirable” organisers. The number of vetting bodies has expanded: the Ministry of Culture must obtain conclusions from regional executive committees and send requests to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and other relevant agencies to screen key individuals, including directors, founders, and employees. The decision period has been extended to 30 working days.

4. New requirements for applicants

The former “experience” criterion is replaced by a “portfolio system”: applicants must submit information about previous events (video, audio, scripts) proving compliance with the Code on Culture, without any time limit. Events held by a company’s founders or employees may also be evaluated.

5. Revised composition of the National Expert Commission

The commission has become heavier and more ideologically charged, now including representatives from the Presidential Administration, the Ministries of Information, Education, and Taxes, as well as loyal media figures such as Ryhor Azaronak and Natalla Karačeŭskaja. Decisions are made by a two-thirds majority rather than a simple majority.

6. Direct prohibitions and obligations

The regulation introduces norms governing organisers’ activities and new commitments: the requirement to approve scripts and programmes; special terms for contracts with artists; a ban on cooperation with “undesirable” persons; the need to obtain an extract from the register for each new artist’s contract; and the requirement to ensure the organiser’s representatives are present at venues; etc.

7. Liability and removal from the register

Any violation (e.g. cooperation with a “banned” artist or intermediary, or failure to obtain the required extract) can result in removal from the register and a two-year quarantine before reapplication (previously, the ban was indefinite).

***

Overall, the level of ideologisation and state interference in cultural life has increased significantly. The procedure has become less transparent and turned into a multi-level approval system involving the commission under the Ministry of Culture, law enforcement bodies, and executive committees. This structure allows the authorities, at any moment, to justify the “unreliability” of any organiser, primarily those from the non-state sector.

CONCLUSION

Between January and September 2025, at least 979 cases of violations of the cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures were recorded in Belarus. These include arbitrary detentions, criminal prosecution, denial of the right to a fair trial, restrictions on freedom of movement, censorship, and other forms of persecution for dissent.

At least 151 representatives of the cultural sphere are currently in places of incarceration or serving sentences of restricted freedom (open-type facilities or home confinement). Repression targets both cultural figures inside the country and political exiles abroad.

At least 18 people from the cultural sector were released through pardons, of whom 15 were deported from Belarus without official release documents, and some even without passports. Upon release, many had their manuscripts, drafts, and personal letters confiscated. Thus, the process of release itself was accompanied by new human rights violations.

Under the pretext of “combating extremism and terrorism”, and through the creation and constant expansion of various lists, commissions, regulations, and decrees, the authorities continue systematic pressure on independent thought, seeking to place culture under total administrative control and to silence its free voices.

The practical and legal support of repressed cultural workers – on both sides of the border – remains an urgent and essential task, particularly in terms of ensuring opportunities for them to continue their professional activities.

[1] The political prisoner and politician Mikoła Statkievič, one of the 52 people granted a pardon, refused to leave the territory of Belarus and was returned to the penal colony.

[2] According to Human Rights Centre “Viasna”.

[3] Home confinement is restriction of liberty without transfer to an open-type correctional facility.

[4] An individual may be convicted under multiple articles of the Criminal Code.

[5] The final sentence, after partial accumulation, was 4 years and 9 months in a penal colony.

[6] The final sentence, after partial accumulation, was 4 years and 6 months in a penal colony.

[7] Dzieciuki — Wikipedia.