[БЕЛ: Чытаць маніторынг па-беларуску]

[РУС: Читать мониторинг по-русски]

This report is based on aggregated information collected by the PEN Belarus monitoring group during the first half of 2025 from open sources, personal contacts, and direct communication with cultural figures. If you wish to report violations (including confidentially) or correct inaccuracies, please contact us at [email protected], t.me/viadoma. The more accurately we can record and analyse the human rights situation in the cultural sphere, the more effectively we can plan our work to support cultural figures and culture-related projects. More information about the monitoring is available here.

NB: To protect users’ information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources if restrictions have been imposed on them per the regulations currently in force in the Republic of Belarus.

Main results

Conditions of incarceration: incommunicado and deterioration of health

Arbitrary detentions

Criminal prosecution

Culture-related materials labelled as “extremist”

“Harmful literature”

Historical heritage and destruction of memorial sites

State policy in the field of culture

Conclusion

MAIN RESULTS

In the first half of 2025, Belarus continued to witness the persecution of individuals for dissent and the expression of opinion. Arbitrary detentions and arrests persisted, alongside politically motivated administrative and criminal prosecutions targeting cultural figures both within the country and in exile. Several new works of fiction and non-fiction were also designated as “extremist materials”.

Several significant developments marked the second quarter of the year. Among them was the continued imprisonment of political prisoner, lawyer, writer, and bard Maksim Znak, who has been held incommunicado for two and a half years. Notably, a U.S.-mediated agreement led to the pardon and subsequent deportation from Belarus of 14 prisoners, including three cultural figures: Natalla Dulina, Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, and Ihar Karniej.

Meanwhile, authorities intensified their crackdown on the Belarusian-language section of Wikipedia, detaining and persecuting several of its administrators. Civil activist Nina Bahinskaja, renowned for her role in preserving Belarusian national memory and recognised as a symbol of the 2020 protests, faced criminal prosecution and trial.

In the realm of media and cultural suppression, the Belarusian Ministry of Information designated the Instagram page of Skaryna Press – a London-based Belarusian book publisher and online retailer – as “extremist material”. The Ministry also expanded its list of banned literature, adding 75 more titles deemed harmful to the nation’s interests.

Symbolic acts of erasure continued with the removal of the bust of Tadevuš Kasciuška (Tadeusz Kościuszko) – a national hero in Belarus, Poland, and the United States – from his ancestral estate in the village of Małyja Siachnovičy in Brest region. Additionally, century-old buildings were demolished to make way for the upcoming “Dažynki – 2025”, the country’s annual rural workers’ festival.

One of the key directions in state policy is the continued strengthening of ideological control – this includes the approval of the “Fundamentals of the Ideology of the Belarusian State” (as outlined in Directive No. 12), a strong emphasis on patriotic education, and preparations for the 80th anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War, with over 150 commemorative events planned. Additionally, new cultural cooperation agreements have been signed between institutions in Belarus and Russia, and there is ongoing support and promotion of artists loyal to the government, among other initiatives.

Persecution in January – June 2025 in numbers:

- 593 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures were documented.

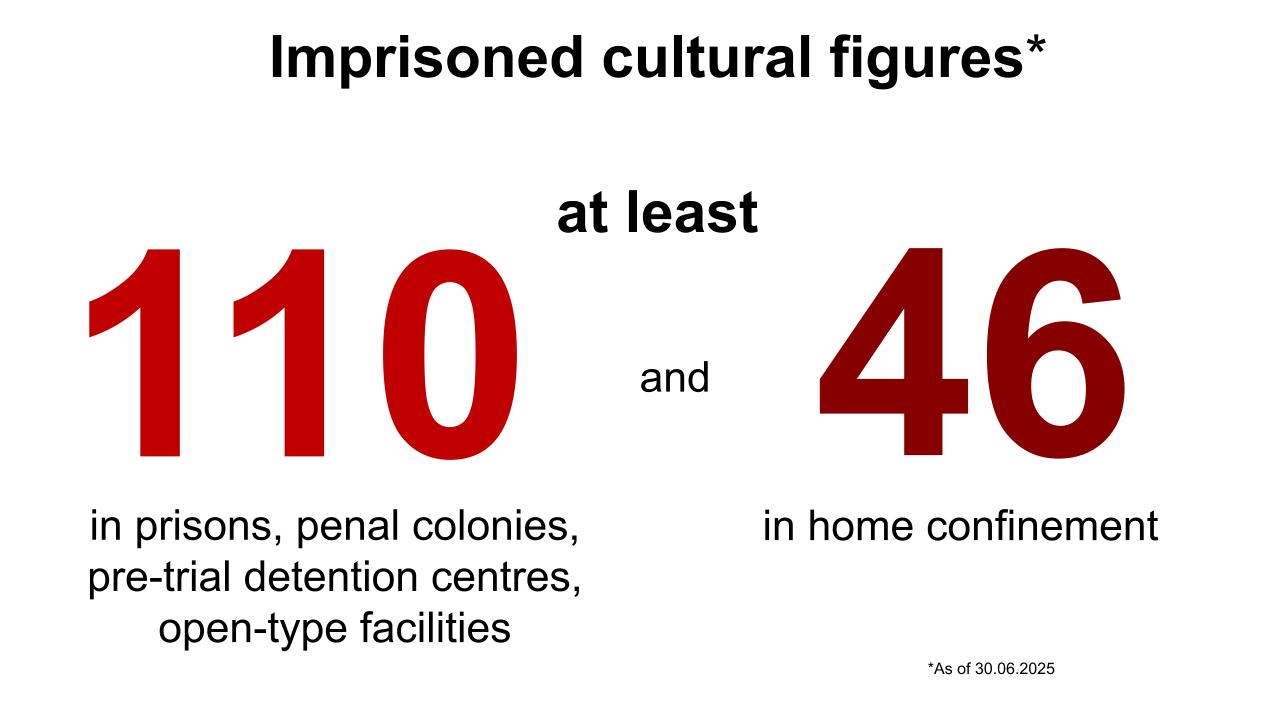

- As of 30 June 2025, there were 1,164 political prisoners [1] in Belarus, among them at least [2] 97 individuals from the cultural sphere.

- A total of at least 156 cultural figures are serving sentences on politically motivated charges in penal colonies, prisons, pre-trial detention centres, open-type correctional institutions, or in home confinement [3].

- Top 10 violations of rights:

- The classification of cultural content and the social media activity of cultural figures as “extremist materials” remains the most frequently recorded violation during the monitoring period, with 183 documented cases. Censorship – including the designation of printed publications as “prohibited for distribution in Belarus” – ranks second, with 103 instances. Rounding out the top three are violations of the right to a fair trial and access to justice, with 63 reported cases.

- Criminal proceedings were initiated against 47 cultural figures. Half of these cases – 23 in total – targeting political emigrants.

- At least 24 cultural figures faced criminal prosecution, including one person tried in absentia. For every fifth person, this has already been the second or subsequent conviction since the 2020 events.

- At least 22 cultural figures were subjected to arbitrary detention or arrest, with two of them detained twice.

- Administrative punishment was recorded in relation to 17 cultural figures, based on 18 administrative offence reports.

- In at least 4 cases, former political prisoners – cultural figures who emigrated after serving sentences involving restriction of freedom in an open-type facility or home confinement – were tried in absentia, and the original verdicts were replaced with harsher penalties.

- An additional 23 cultural figures were added to the “List of Citizens of the Republic of Belarus, Foreign Citizens or Stateless Persons Involved in Extremist Activities”, and 7 more to the “List of Organisations and Individuals Involved in Terrorist Activities”.

- The Ministry of Information included 17 documentary, historical, and fiction books in the “National List of Extremist Materials”.

- 75 printed publications were added to the list of materials deemed allegedly harmful to the national security of the Republic of Belarus.

- 47 incidents of improper treatment of historical heritage sites and memorial places were documented.

The observed trends:

- Since 5 March 2025, public access to the electronic schedule of court hearings on the Supreme Court’s website has been disabled, significantly hindering the ability of human rights defenders to monitor administrative and criminal trials – particularly those involving cultural figures. Additionally, the “Special Proceedings” section was removed from the website.

- For the first time, violations related to the protection of historical and cultural heritage have ranked among the top ten most frequently recorded incidents during monitoring. This trend is primarily attributed to growing challenges in tracking politically motivated persecution.

- The number of cultural figures facing repeated convictions – two or more times – is on the rise, including individuals who are already serving sentences.

- Detentions and the initiation of criminal proceedings against individuals returning to Belarus from abroad continue to take place.

- Sentences for cultural figures convicted of freedom-restricting offences are increasingly revised through trials in absentia, particularly for those who left the country following their convictions.

- The posting of information on BYMAPKA – a platform that maps Belarusian businesses abroad – has become a new pretext for persecution and intimidation.

- A landmark case was recorded in which the court, rather than imposing imprisonment or restricting freedom, placed activist Nina Bahinskaja – one of the most prominent symbols of the 2020 Belarusian protests – under “preventive surveillance”.

- Some cultural figures were pardoned just before the end of their sentences – sometimes with as little as six months, a month, or even a week left to serve.

- Individuals who received pardons were forcibly deported without receiving any official documentation verifying their release, such as certificates or confirmation papers.

- The designation of materials related to imprisoned cultural figures as “extremist” continues – even in cases where individuals have long been serving their sentences. This classification primarily targets their books and social media accounts.

- A new list titled “harmful literature” has appeared on the website of the Belarusian Ministry of Information since late 2024.

- The trend that began in the first quarter of 2025 – a slowdown in the forced liquidation of NGOs – has continued. According to Lawtrend’s monitoring, the process has become more selective. In the first half of the year, eight organisations were dissolved, three of which were cultural.

CONDITIONS OF INCARCERATION: INCOMMUNICADO AND DETERIORATION OF HEALTH

Incommunicado refers to the complete isolation of a political prisoner from both the outside world and their immediate social circle – meaning no contact with family members, legal counsel, or friends. Since February 2023, this practice has become increasingly widespread in Belarusian incarceration facilities.

One example is cultural manager and blogger Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, who was among the 14 individuals pardoned and released on 21 June 2025. He spent 835 days – more than two years – in a state of total information blackout, and nearly three years in solitary confinement. In post-release interviews, Cichanoŭski described complete isolation as one of the most severe ordeals of his five-year imprisonment.

In the case of businessman and philanthropist Viktar Babaryka, no information was available for nearly two years until 8 January 2025, when pro-government media released updated photos and video footage.

Musician and cultural manager Maryja Kalesnikava remained fully isolated until a brief meeting with her father at the penal colony on 12 November 2024, marking nearly two years in incommunicado mode. She is currently once again denied any contact with the outside world.

Lawyer, writer, and bard Maksim Znak has been completely cut off from communication for two and a half years. His last known letter was dated 9 February 2023. Since then, neither his family nor his lawyer has been granted access to him.

Health of political prisoners

The conditions imposed on political prisoners in Belarusian incarceration facilities have had a profoundly damaging effect on their physical health. Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, currently undergoing a comprehensive medical evaluation, reports that doctors prescribed him 19 daily medications at the preliminary stage alone. His tests revealed a complete deficiency of vitamin D. Upon release, he was severely emaciated, weighing just 79 kilograms – half of his body weight at the time of his arrest in May 2020.

Similar accounts of health deterioration under inhumane incarceration conditions have come from journalist Ihar Karniej, who spent two years in prison and was pardoned on the same day as Cichanoŭski. He recalls:

“Out of the entire chain of vitamin deficiencies, the equipment didn’t register any vitamin D at all. No wonder: in solitary confinement, you can go months without seeing the sun, the sky, or feeling the wind. […] The first fresh produce didn’t appear until late autumn, when they started serving boiled cabbage as a side. […] Over time, words like tomato, cucumber, and radish disappear from your vocabulary – they’re simply no longer relevant. This is especially true for so-called ‘extremists’, who are systematically denied food parcels and limited to the most minimal grocery allowances. Receiving a medical parcel is almost an impossible quest”.

In the first half of 2025, alarming reports regarding the health of imprisoned cultural figures have emerged from multiple penal colonies:

- Vaclaŭ Areška, a cultural scholar and editor serving his term in Penal Colony No. 22, suffers from severe vision impairment – he is no longer able to see beyond arm’s length. Despite this, authorities have refused to grant him disability status.

- Aleś Bialacki, writer and human rights advocate held in Penal Colony No. 9, is experiencing a marked deterioration in his eyesight.

- Siarhiej Sacuk, science fiction writer and journalist imprisoned in Penal Colony No. 15, suffers from high blood pressure and joint disease.

- Valeryja Kasciuhova, political analyst and publicist incarcerated in Penal Colony No. 4, experiences occasional loss of consciousness. The essential medications she requires are not produced in Belarus, and the colony administration prohibits their delivery.

The use of complete isolation (incommunicado) and the denial of adequate medical care constitute systematic violations of prison conditions and the right to health for political prisoners in Belarus.

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS

In the first six months of 2025, at least 22 cases of arbitrary detention and arrest involving cultural figures were documented, with two individuals detained more than once.

On 6 February, Andrej Niesciarovič, owner of the ethnographic shop Cudoŭnia in Hrodna, was arrested on charges of participating in the 2020 protests. On 28 March, poet, translator, and former editor of the Babrujsk Courier, Anatol Sanacienka, was sentenced to 15 days of administrative arrest for allegedly “disseminating extremist materials”. On 19 May, non-fiction author Cina Pałynskaja disappeared from public contact; it was later confirmed that she had been detained as part of a criminal investigation. On 4 June, news emerged of the detention of Alaksandr Chichiel, a singer-songwriter from Miadzieł. Pro-government propagandists claimed he had sung “silly songs against the special military operation (SVO), against our government, against Russia, and Victory Day”. On 25 June, Aleh Chamienka, frontman of the contemporary folk band Pałac, was arrested for alleged collaboration with an independent Belarusian media outlet labelled “extremist” by the authorities.

A notable development during this period was the detention of Belarusian-language Wikipedia administrators [4]. After 13 March, the Wikipedia community lost contact with the user Kazimier Lachnovič, one of four administrators of the Taraškievica (classical Belarusian) section. His last contributions were dated 12 March. While there is no official confirmation of his detention or real identity, there is strong reason to believe he was detained.

On 20 March, a week after Lachnovič’s disappearance, a major state-run propaganda outlet, Belarus. Segodnia published an article discrediting Wikipedia. It described the platform as a “tool of information warfare” against post-Soviet states and claimed the Belarusian section was edited from abroad, namely, Poland. The piece called for the creation of a “domestic alternative based on scientific data and verified sources”.

On 17 April, administrator Volha Sitnik (username: Homelka) also ceased editing and lost contact with the community. It was later confirmed that she had been briefly detained that day and released. However, on 7 May, she was detained again, spent 10 days in the Akrescina detention centre, and is currently being held in pre-trial detention. In June, her Telegram account was used by Belarusian security services to distribute state-controlled content in diaspora group chats.

On 15 May, Maksim Lepušenka, editor and the longest-serving active administrator of Belarusian Wikipedia, was arrested. As of writing, he remains in pre-trial detention and faces charges under Article 342 of the Criminal Code for participation in the 2020 protests.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION

In the first half of 2025, 47 new cases of politically motivated criminal prosecution targeting cultural figures were documented. These include: 5 individuals currently recognised as political prisoners, 2 former political prisoners prosecuted after completing their original sentences, 17 cultural figures residing in Belarus, and 23 individuals living in political exile.

From January to June, at least 24 cultural figures were subjected to criminal prosecution, including one person convicted in absentia.

The most common grounds for in-person criminal prosecution included [5]:

- Participation in peaceful protests in 2020 (Articles 342 and 342-2 of the Criminal Code) – 8 individuals.

- Alleged involvement in “extremist activity” (Articles 361-1, 361-2, 361-4) – 8 individuals.

- Public criticism of state policy and related expressions (Article 130) – 3 individuals.

- Acts of dissent or disobedience in places of incarceration (Article 411) – 2 individuals.

Julija Łaptanovič – librarian; convicted under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code, sentenced to two and a half years in a penal colony [6]. Daniel-Lindsey Keita – choir member; charged under Article 342, – [7]. Michaił Łabań – artisan and owner of the jewellery workshop Samarodak; Article 361-2, sentenced to two and a half years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility [8]. Alena Badziaka – English teacher; Articles 130 and 361, sentenced to two years in a penal colony. Eduard Babaryka – cultural manager and businessman; charged under Article 411, –. Kirył Vieviel – musician and screenwriter; Articles 361-1 and 130, –. Nastassia Achramienka – photographer; Article 367, sentenced to home confinement. Alaksandr Franckievič – writer and anarchist; Article 411, –. Anžalika Alasiuk – Belarusian language and literature teacher; Article 368, –. Vieranika Žałuboŭskaja – actress, model, and flight attendant; Article 342, sentenced to one year in a penal colony. Palina Pitkievič – writer and journalist; Article 361-1, sentenced to three years in a penal colony. Viktar Kucharčuk – historian and educator; Article 130, –. Nakanishi Masatoshi – Japanese language teacher; Article 358-1, sentenced to seven years in a penal colony. Alena Pankratava – writer and journalist; Article 342, sentenced to home confinement. Andrej Niesciarovič – owner of the ethnographic shop Cudoŭnia; Article 342, sentenced to one and a half years of restricted freedom in an open-type facility. Nina Bahinskaja – cultural and civic activist; Article 342-2, placed under preventive surveillance. Jaŭhien Bojka – cultural activist; Articles 361-1 and 361-3, sentenced to five years in a penal colony. Vadzim Pažyviłka – former director of children’s and popular science publishing houses; Article 361-2, sentenced to home confinement. Alena Brazinskaja – English teacher; Article 342, sentenced to home confinement. Siarhiej Sałažencaŭ – IT specialist and dance competition laureate; Article 361-2, sentenced to a penal colony. Alaksandra Ašurka – founder of Devil Dance Studio; Article 342, sentenced to home confinement. Aleh Zielanko – head of the historical reenactment club Mindouh; Article 361-4, –. Pavieł Łaŭrynovič – local historian scholar; Article 342, sentenced to home confinement.

The Nina Bahinskaja case

One of the most emblematic criminal cases of the first half of 2025 was the prosecution of 78-year-old civil activist Nina Bahinskaja – a symbol of peaceful protest in Belarus. A geologist by training, she has spent decades openly and consistently defending the right to use national symbols. For this, she has been subjected to ongoing state pressure: she has been repeatedly detained and fined, had her summer house and land plot confiscated, and been stripped of part of her pension, among other measures.

In early May, it was revealed that a criminal case had been opened against Bahinskaja under Article 342-2 of the Criminal Code (Repeated violation of the procedure for organising or holding mass events). The grounds for the case were multiple administrative penalties issued against her in 2024 under Article 24.23 of the Administrative Code for using national symbols. Case materials cited the discovery of a white-red-white flag and a poster featuring the Pahonia coat of arms during a search of her home, as well as her detention at Independence Square in Minsk near the Red Cathedral (closed by the authorities), where she had tied ribbons in national colours to a tree.

During the investigation, Bahinskaja was sent for psychiatric assessment multiple times. On 30 May, Minsk’s Pieršamajski District Court, in a closed hearing, found her guilty but applied Article 79 of the Criminal Code (Conviction without the imposition of punishment) and placed her under preventive supervision.

Bahinskaja has declared her intention to seek the return of personal belongings seized during the investigation – including handmade badges and flags bearing national symbols. According to the court ruling, these items are to be destroyed.

The Anton Matolka case

Among the most notable cases of the reporting period is the criminal prosecution and conviction in absentia of blogger, photographer, and cultural manager Anton Matolka. He was found guilty on 13 separate counts under the Criminal Code, including the charge of “state treason”. Following six months of trial in absentia, on 3 June 2025, the Hrodna Regional Court sentenced Matolka to 20 years of imprisonment and fined him 2,000 base units (equivalent to 84,000 BYN, or approximately 25,670 USD).

According to the ruling, which Matolka later published on Facebook, the court also ordered the seizure of his personal property. This included: a 1997 Mazda MX3, a garden house and land plot, small amounts of money held in bank accounts: €15.06, BYN 30.77, and €1.31, and an iPad tablet (model A1337). The list of items officially recognised as material evidence in the case includes: several DVD-R and CD-R discs, six media badges issued in the name of A. G. Matolka, and two lapel pins bearing the inscription “Freedom”.

CULTURE-RELATED MATERIALS LABELLED AS “EXTREMIST”

In the first half of 2025, at least [9] 183 items were added to the National List of Extremist Materials in Belarus. These included books, songs, YouTube channels, and social media accounts on platforms such as Telegram, Instagram, and Facebook, along with various visual and other materials connected to cultural content or cultural figures.

The report, summarising the monitoring results from the first quarter of 2025, listed most of the materials designated “extremist” during that period. In the second quarter of 2025, the following culture-related resources were added to the list:

- Instagram accounts belonging to: publisher Ihar Ivanoŭ, writer Saša Filipienka (Sasha Filipenko), craftswoman Rehina Łavor, and trumpeter Timote Suladze.

- Facebook accounts of philosopher Pavieł Barkoŭski and musicians Lavon Volski and Alaksandr Dzianisaŭ (along with Dzianisaŭ’s VKontakte profile).

- YouTube channels of musician Siarhiej Michałok BRUTTO NOSTRA, singer-songwriter Alaksandr Bal (as well as five of his social media accounts), and performer Alaksandr Chichiel (his channel was removed by state security following his arrest); and those of imprisoned writer and anarchist Mikałaj Dziadok, including his associated social media pages.

- The website and social media platforms of BY teatr, a theatre bureau based in Warsaw; pages and the logo of the Hrodna-based folk-punk band Dzieciuki, accompanied by a sweeping formulation: “Any visual material (images, digital watermarks, etc.) or the text ‘DZIECIUKI’, with or without accompanying words, regardless of the medium (flags, banners, emblems, patches, badges, clothing items, household goods, etc.), including digital photos and videos depicting any events, scenes, episodes, or frames in electronic and print media”.

- A particularly concerning development was the inclusion in the list of “extremist materials” of the Instagram page of Skaryna Press – a London-based publisher and online store specialising in Belarusian books. In response, the editorial team issued a public statement firmly rejecting the authority of a court under “presidential” control in Belarus to rule on matters of intellectual and creative freedom. The statement described the designation as an act of unlawful interference and a politically motivated attempt to exert pressure on the publisher’s team, authors, and readership. The editors also emphasised that Skaryna Press is a vital contributor to the preservation and development of the Belarusian language and culture in exile: in just two and a half years, the publisher has released over 50 titles, including poetry, essays, fiction, and academic works.

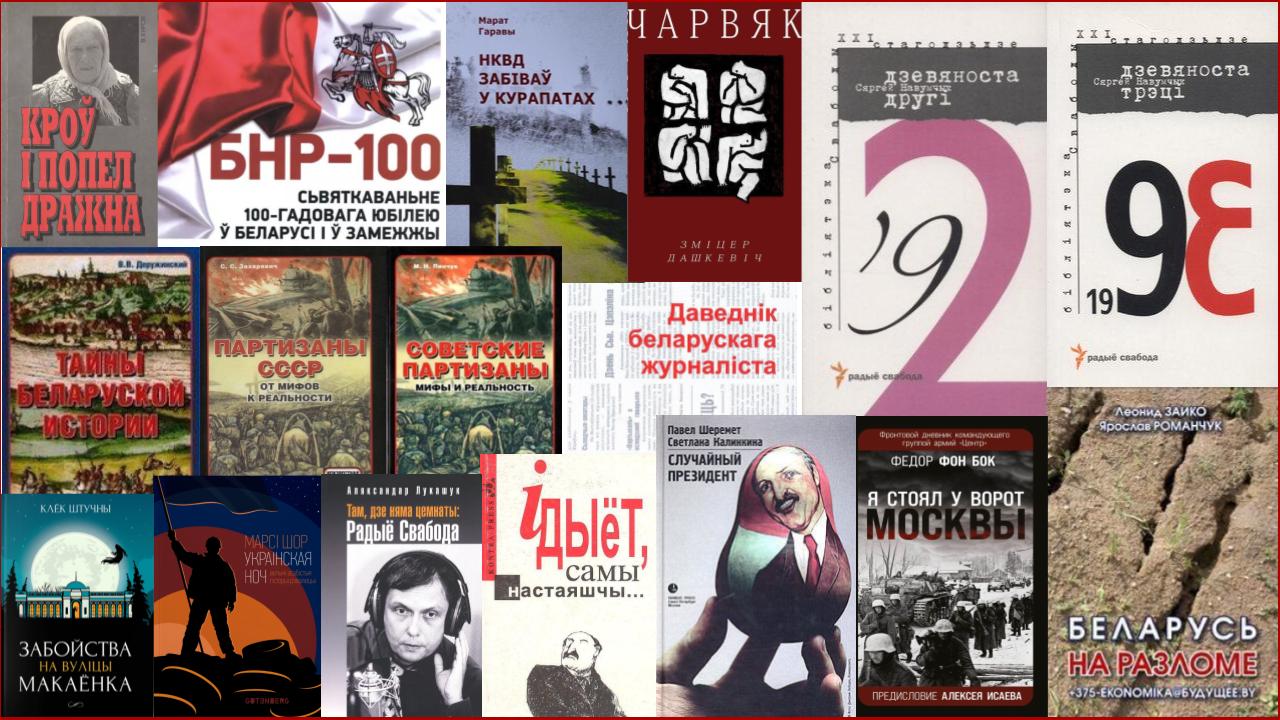

In total, during the first half of 2025, the Ministry of Information designated 17 documentary, historical, and fictional books as “extremist”. These included: Čarviak (The Worm), a prison memoir by political prisoner Dzmitry Daškievič; two historical accounts of early Belarusian independence by Siarhiej Navumčyk – Dzievianosta druhі (Ninety-Second) and Dzievianosta trecі (Ninety-Third); three documentary books about the Belarusian partisan movement; a detective novel by Klok Štučny, Murder on Makajonka Street, set in post-2020 Minsk, as well as several other titles in various genres.

The Ministry of Information’s increasingly absurd list has been growing unchecked for years. It has become nearly impossible to keep track of, let alone adjust one’s internet usage in Belarus, to avoid violating it. At a Media Community Forum in June this year, Minister of Information Marat Markaŭ stated: “More than 18,000 resources have already been restricted, and nearly 7,000 have been designated as extremist. Last year alone, over 3,150 were blocked. In just the first five months of this year, we’ve already matched those numbers! The same applies to books – we have already declared 110 titles harmful to our children”.

“HARMFUL LITERATURE”

The emergence of a list of printed publications deemed capable of “harming the national interests of the Republic of Belarus” marks a new form of censorship in the country. Its creation became possible following the entry into force on 22 October 2023 of the Law of the Republic of Belarus “On Amendments to the Law ‘On Publishing in the Republic of Belarus'”. Among other provisions, the law granted the Ministry of Information the authority to compile and maintain such a list.

The first official version of the list was published on the ministry’s website in November 2024. It initially included 35 titles, with the top three being books on Belarusian history. The remaining 32 were Russian publications, mainly focused on LGBTQ+ topics, sex education, and content marked 18+. Since then, the list has been regularly expanded, with 30 titles added in January 2025, 27 more in April, and a further 18 in May. By mid-2025, the list had grown to 110 entries, 75 of which were added during the first half of the year.

According to the National Commission for the Evaluation of Symbols, Attributes, and Informational Products – which issues official rulings on such matters – these books are considered “sources of propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations, pornography, violence and cruelty, drug use, and the promotion of subcultures not traditional to Belarusian society”. If “harmful literature” is found to be distributed within Belarus, the Ministry of Information is authorised to revoke the state registration certificate of the distributor.

Realistically, this list is part of a broader state policy of controlling the information space – a tool of political and ideological censorship.

Among the books banned in 2025 are titles by internationally acclaimed authors and works dealing with history, identity, trauma, and human rights: two books by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Anne Applebaum, Gulag and Iron Curtain, the classic LGBTQ+ novel Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin, globally recognised literary works such as The Wasp Factory by Iain Banks, Lullaby by Chuck Palahniuk, Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell, and A Little Life and To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara.

Many of the banned books have also been adapted into internationally distributed films and series. Examples include Cabaret (1972), directed by Bob Fosse and based on Christopher Isherwood’s semi-autobiographical novel Goodbye to Berlin (1945), about life in Germany during the Nazi rise to power. The film was added to the US National Film Registry [10] in 1995. Romantic drama Call Me by Your Name (2017) is based on the novel by André Aciman. Björnstad (Beartown), a Swedish mini-series, is based on the novel by Fredrik Backman. Heartstopper, a British coming-of-age web series, was adapted from the graphic novel by Alice Oseman.

The complete list of literature deemed by the Belarusian authorities to be “harmful to national interests”, as well as those designated as “extremist materials”, can be found on PEN Belarus’s website under the section titled Banned Books.

HISTORICAL HERITAGE AND DESTRUCTION OF MEMORIAL SITES

In the first half of 2025, 47 documented violations were recorded relating to the preservation of cultural heritage – both officially recognised historic and cultural assets and sites of memory without legal protection. These included: inappropriate treatment of immovable heritage sites, including their partial or complete destruction; absence of protected status for certain architectural monuments; anti-restoration practices – disregard for original colour schemes, destruction of façade decor, and crude “Euro-renovations”; loss of unique works of art; indifference or disrespect from officials towards the preservation of memorials; and broader failures in safeguarding architectural landmarks, burial sites, and commemorative spaces.

Destruction of architectural monuments

On 7 February 2025, the Telegram channel Spadčyna reported the critical condition of a historic wooden windmill – Dutch-type vernacular structure located in the village of Šajki (Kleck district). Built in the late 19th or early 20th century and granted protected status in 1987, the mill had been neglected by local authorities for nearly four decades. It had fallen into disrepair in recent years. In 2024, the rural council commissioned the Belzhilproekt institute to draft an emergency stabilisation and conservation plan, including a preliminary cost estimate and engineering assessment. However, prolonged inaction led to irreversible loss: on 7 July, the windmill collapsed during a storm.

There were also cases of deliberate destruction. In late April, Mahiloŭ’s first city power plant, built in 1910 and surviving two world wars, was demolished. Though abandoned for years, preservation advocates had submitted a detailed proposal to grant it official heritage status – unsuccessfully.

In June, a century-old kindergarten on Vasilka Street 5 in Hrodna was torn down. The building was being converted into a residential property by the developer SpektrInvestGroup. To circumvent regulations prohibiting the demolition of listed properties, the developer left a small fragment of wall intact. While the building did not hold formal cultural status, it was part of a designated historical protection zone in the city centre and, under such conditions, should not have been subject to demolition. Reusing old bricks in new construction cannot be equated with preserving architectural heritage.

Another recurring factor in the destruction of historical buildings is preparation for Dažynki, an annual harvest festival increasingly resembling a state-orchestrated showcase. Each year, a new town is chosen to host the event, and local authorities rush to “beautify” facades, often at the expense of historic urban fabric. This year’s regional Dažynki 2025 is scheduled for 20 September in Zasłaŭie. As part of the preparation, two century-old wooden structures were demolished – both had been illegally delisted around a decade ago. A shop building from 1912–1914 on Sovetskaya Street 34 was razed in early February 2025, followed by a tavern from 1911–1914 at Savieckaja Street 36 on 18 March.

One glaring example of anti-restoration and forced Russification is the so-called “renovation” of the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin in the village of Paciejki (Kapyl district). Built in 1792 and considered a significant example of folk wooden architecture, the church was fitted with a bright ultramarine roof and gold onion domes after the works, completely distorting its historical appearance.

Destruction of memorial sites: Tadevuš Kasciuška (Tadeusz Kościuszko)

On 11 May, it was reported that the memorial plaque honouring Tadevuš Kasciuška had disappeared from the commemorative stone near the village of Kaściuškava in the Horki district (Mahiloŭ region). Kasciuška – leader of the Polish uprising of 1794 and national hero of Belarus, Poland, and the United States – had been commemorated at the site for years.

Around the same time, a bust of Kasciuška, created by sculptor Balbina Switycz-Widacka in 1932, was removed from its location at his ancestral estate in the village of Małyja Siachnóvičy (Žabinka district, Brest region). The bust had stood there since 1988. It was removed along with all mentions of the general from the website of the local history museum, at whose entrance the monument had been placed. Previously, the museum housed a distinctive collection dedicated to the life and legacy of the “hero of three continents”. This exhibition has since been replaced with propagandistic displays focusing on Soviet partisans and the so-called “genocide of the Belarusian people”.

Although the bust appears to have been removed recently, it was confirmed to be in place as late as autumn 2024, the transformation of the museum exhibition likely occurred earlier.

STATE POLICY IN THE FIELD OF CULTURE

Patriotic upbringing as a cultural policy priority and a tool of intimidation

In a recent speech, the Minister of Culture, Rusłan Čarniecki, emphasised that patriotic themes occupy a central role in contemporary Belarusian culture. At a press conference on the development of historical and cultural tourism in Belarus, Nadzieja Aŭdziej, a consultant at the Ministry’s Department of Culture and Folk Art, confirmed that “the theme of patriotic education and the 80th anniversary of Belarus’s liberation and the Great Victory” is a defining priority. According to her, this theme currently shapes the work of cultural institutions – museums, libraries, local cultural centres, and other entities.

Patriotism and patriotic upbringing of youth, military-patriotic training, themed camps, patriotic campaigns, and related projects have remained persistent themes in recent years. “Fostering patriotism, including readiness of every citizen to defend the state’s interests, constitutional order, and territorial integrity”, has been officially designated as one of the key goals of state ideological work. This was codified in Presidential Decree No. 12, signed by Łukašenka on 9 April 2025, which aims to “raise ideological work to a qualitatively new level”. The decree, titled “On Implementing the Fundamentals of the Ideology of the Belarusian State”, is an attempt by the regime to craft a national idea “capable of capturing the hearts, minds, and souls of the people”.

Just one month later, on 14 May, the Ministry of Sports and Tourism issued Resolution No. 10 (dated 30 April 2025), which further tightened the professional and ethical requirements introduced in July 2023 for tour guides and interpreters. Among other things, these professionals are now required to:

- Understand and incorporate the fundamentals of state ideology as outlined in Decree No. 12 in their work;

- Participate in preserving historical memory and national values;

- Promote a positive image of the country and its “unique Belarusian model of social development”.

However, under the guise of patriotic education and historical remembrance, the state often conceals tactics of intimidation, coercion, and ideological indoctrination. Two high-profile incidents involving teenagers occurred in the second quarter of 2025 that illustrate this dynamic:

- In May, a TikTok video went viral in which six teenage girls from Mahiloŭ were shown making an obscene gesture (middle finger) towards the 9 May Victory Day fireworks and turning their backs to them. As a “disciplinary measure,” they were taken to the memorial complex in the village of Borki – the site of a 1942 massacre of civilians – where they were forced to watch Elem Klimov’s harrowing war film Come and See. A Belarusian Orthodox priest also delivered a lecture.

- In June, two schoolboys from Minsk posted a TikTok video in which they angrily tore up their Year 9 history exam papers. They were later made to record a “repentant” video in front of Victory Square, where they apologised for their actions and laid carnations at the Victory Monument.

These incidents clearly illustrate how genuine dialogue is replaced with performative re-education, turning historical memory into a blunt instrument for intimidating the younger generation.

Cultural integration with Russia

In the first half of 2025, cultural integration between Belarus and Russia continued actively, particularly through the signing of cooperation agreements between various institutions in the cultural field. Only in June and only during the sectional meeting of the 12th Forum of Belarusian and Russian Regions, held in Nizhny Novgorod on 26-27 June (as part of the integration processes, 211 agreements and memorandums on the development of bilateral relations were signed there), a number of documents on cooperation between Belarus and Russia in the field of culture were signed. Key Belarusian signatories included: the National Library of Belarus, the National Art Museum, the Janka Kupała State Literary Museum, and the Bolshoi Opera and Ballet Theatre of Belarus. The Ministry of Culture’s Telegram channel highlighted these actions as evidence of “our close cooperation in the cultural sphere, strengthening ties and opening new horizons for joint projects and value exchange”.

Such collaborations continue to be positioned as a response to Western sanctions and international isolation.

Censorship at graduation events: ‘stop lists’ and approved playlists

As is customary, Belarus held graduation celebrations at the end of the academic year. These events again came under strict surveillance: each school’s programme had to be officially approved by the school administration.

It was revealed that the so-called “stop list” – a list of banned performers first made public in February 2023 – remains in effect. It currently includes 87 names, spanning Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Russian artists.

In parallel, a letter from the Ministry of Culture dated 16 June 2025, aimed at “ensuring a high level of organisation and artistic quality“, recommended a list of 134 approved musical tracks for school events. These included, notably, three songs by Hanna Błahava – a police officer, soloist with the wind orchestra of the Minsk City Executive Committee’s Department of Internal Affairs, and prominent representative of Belarus’s pro-government music scene. In March 2025, she was awarded the Francis Skaryna Medal by presidential decree.

The guidance stated: “When preparing the musical programme, we recommend that the listed works by Belarusian performers be evenly distributed throughout the event. The beginning of the musical programme should be rich in works with a patriotic orientation. Please ensure strict control over musical content at the events mentioned above“.

CONCLUSION

In the first half of 2025, at least 593 violations of cultural rights and the rights of cultural figures were recorded in Belarus. These included criminal prosecution, arbitrary detentions, censorship, and the designation of materials as “extremist”. At least 156 individuals associated with the cultural sector remain imprisoned or subject to restrictions on their freedom. Repressive actions continue both within the country and against political émigrés abroad.

One of the most prominent trends remains the systematic labelling of cultural content and the social media accounts of cultural figures as “extremist”. No fewer than 183 such cases were recorded during the reporting period. An additional 75 books were added to the new official list of so-called “harmful literature”, which functions as a tool of ideological and political censorship. Against the backdrop of monument dismantling and the destruction of historical sites for state-led events, the assault on national memory continues.

The use of incommunicado remains widespread, in some cases lasting for years and often accompanied by severe deterioration in the health of political prisoners.

[1] Per Viasna Human Rights Centre’s data

[2] The number of persecuted cultural figures is not definitive, as many cases do not come to light immediately.

[3] Restriction of freedom without placement in an open-type correctional facility.

[4] A multilingual, publicly accessible online encyclopedia with freely available content.

[5] An individual may be convicted under multiple articles of the Criminal Code.

[6] The final sentence, imposed through partial aggregation, was 4 years and 9 months of imprisonment in a penal colony.

[7] Sentence unspecified (hereinafter).

[8] The final sentence, imposed through partial aggregation, was 4 years and 6 months of imprisonment in a penal colony.

[9] Not all materials can be clearly identified as cultural or as originating from cultural figures.

[10] Cabaret (1972) — Wikipedia