Belarusian PEN Questionnaire

What do writers think about certain facets of the creative process, the new challenges facing masters of the word, their literary taboos and sins, dreams and temptations? The answers to this questionnaire are not only mini-portraits of remarkable creators but also a kind of mirror reflecting the spirit of our organization.

1. Creation

What devil drives you to sit down at your writing desk? Do you keep any amulet or totem on it? Do you have a starting ritual?

Creativity is a way to resist the absurdity of this world.

As for a protective charm, on my desk sits a little stone from the Dvina River, recently given to me by fellow Polatsk natives during a meeting in Scandinavia.

Nearby, there is also a gift very important to me—a reproduction sent for New Year by a friend in Germany. It is a drawing of the scholar-encyclopedist, mechanic, and inventor Gabriel Gruber, a Slovene by birth, who in the late 18th century was a professor at the Polatsk Jesuit College and the originator of the idea to transform it into an academy with the status of a university—which later came to pass. The drawing depicts the college’s gallery.

As for the starting ritual, it does exist, but it is too intimate to share.

What is the nature of your creative impulse, your illumination? Do you rely more on notebooks—or memory, life’s conflicts?

And dreams as well.

2. Creators

Who has influenced your literary style the most? Whose example do you measure yourself against? Whose impulses do you hear most clearly?

A long time ago, critics used to write that Uladzimir Karatkievich influenced me the most. But later, one literary scholar refuted this, saying: in Karatkievich there is painting, while in Arlou there is graphics. It seems he was right.

Do you ever ask anyone to read your text before you hand in the manuscript?

Most often, I ask myself, but a slightly different version of me. For example, a month later. Sometimes even a year later.

If you were offered a spiritual séance with the ghost of a writer, who would it be, and what would you like to learn from them?

I can never choose just one person in any field: an artist, a composer, let alone a writer.

What I would like to know is something these “ghosts,” as you call them, would never be able to answer anyway: which of my books are read fifty years from now—and whether they are read at all? But if the “ghosts” had the ability to see the future, then I would have it too.

Your top list of writers—members of Belarusian PEN?

In this list there would certainly be not only PEN members.

Whom and what have you read lately?

Recently, I’ve been working on the second part of one of my historical books, so I have to read a lot of reference and popular science texts and books—in both print and electronic form.

As for other literature, in its various incarnations, I haven’t read much: One Must Imagine Sisyphus Happy by Valyantsin Akudovich, last year’s Giedroyc Prize laureate; Tears to the Wind by Darya Byalkevich; the long-awaited poetry collection There, Beyond the Wall by Taciana Niadbaj, who, like me, dreams of our native Dvina.

As for translations: collections of poetry by Wisława Szymborska and Czesław Miłosz, and now I am making my way through The Doll by Bolesław Prus.

A special reading experience was The Iliad, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and the yet unpublished Aeneid, which came to life in Belarusian thanks to Lyavon Barshcheuski.

3. Creativity

What is the strangest place where inspiration has ever come to you?

First, I’d like to say that I do believe in this unusual state we conventionally call inspiration—although, for example, Jan Parandowski, the author of the famous The Alchemy of the Word, wrote that it has gone out of fashion. I prefer Friedrich Schiller’s definition, who called it a surprise of the soul. I would add—a surprise of the mind as well.

Once I encountered such a surprise in the middle of my beloved Lake Lyukhava near Polatsk. I was swimming, and a grass snake approached me. It froze like a sphinx, as if to say that it was only pretending to be a snake. I replied: perhaps I, too, am only pretending to be a human. We swam away into our separate illusions, but that strange state would not let me go.

There could be a whole anthology of similar episodes.

What do you consider the greatest literary myth?

Perhaps I don’t know world literature well enough to speak about it.

As for our national literature, there is a myth that is cultivated: that foreign readers are interested in us, Belarusian writers (and our works), only as witnesses or as victims.

Which sacred book of Belarusian literature are you tempted to rewrite the ending of?

Unlike some of my colleagues, I have never rewritten my endings. When republishing, I simply put the date: that’s who I was then. And I don’t even think of rewriting anyone else’s endings.

What question would you like to hear from readers but haven’t yet?

Since school, I have believed it’s wrong to give hints.

Do you believe that words can change the Belarusian world?

As we know, in 1918, Belarusians regained the status of a nation-state—under their modern name—mainly thanks to people of the word. Our politicians were also writers, publicists, publishers, historians, and more.

Today, in this time, people of the word are preserving the Belarusian language—and more broadly, the culture—as a guarantee of preserving the state. And that leaves the possibility of changing the Belarusian world itself. The time will come, and the word—pardon the pun—will yet speak its word.

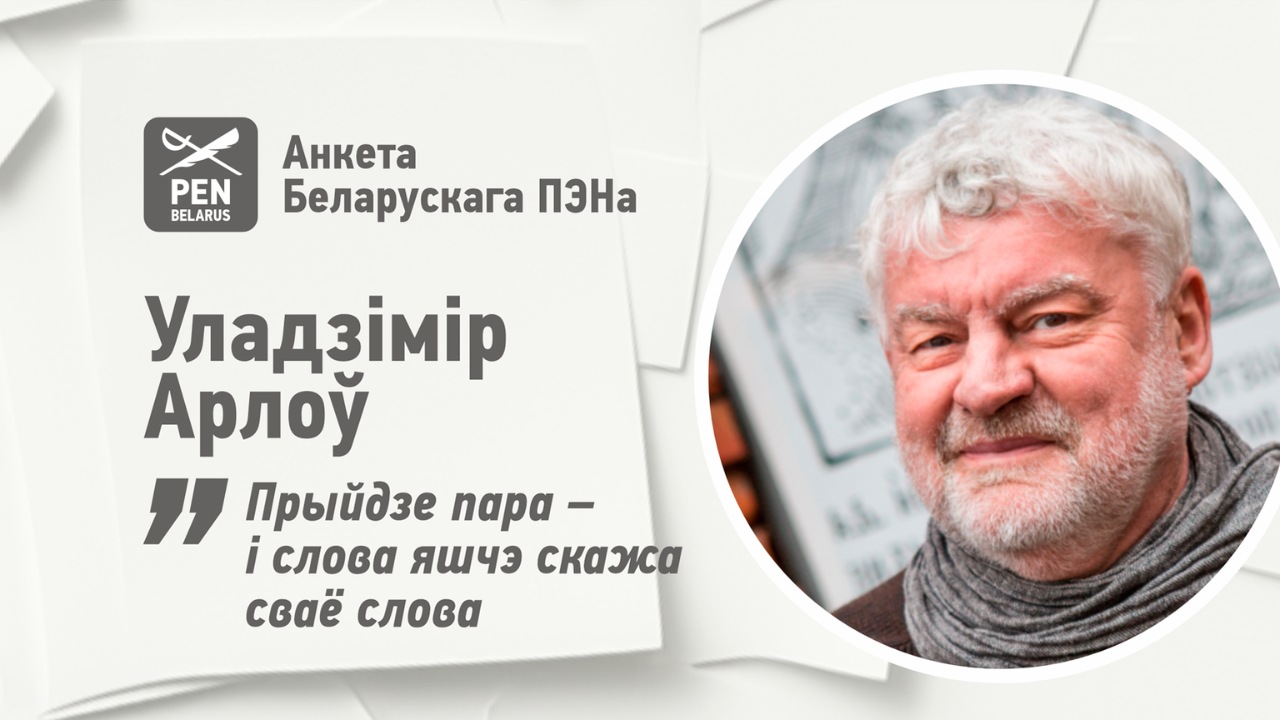

Uładzimir Arłoŭ is a Belarusian prose writer, poet, and historian.

He is the author of more than fifty books and the laureate of numerous awards, including the Francišak Bahuševič Prize, the Ales Adamovich Prize, the Ciotka Prize, the Jerzy Giedroyc Prize, among many others—both Belarusian and international.