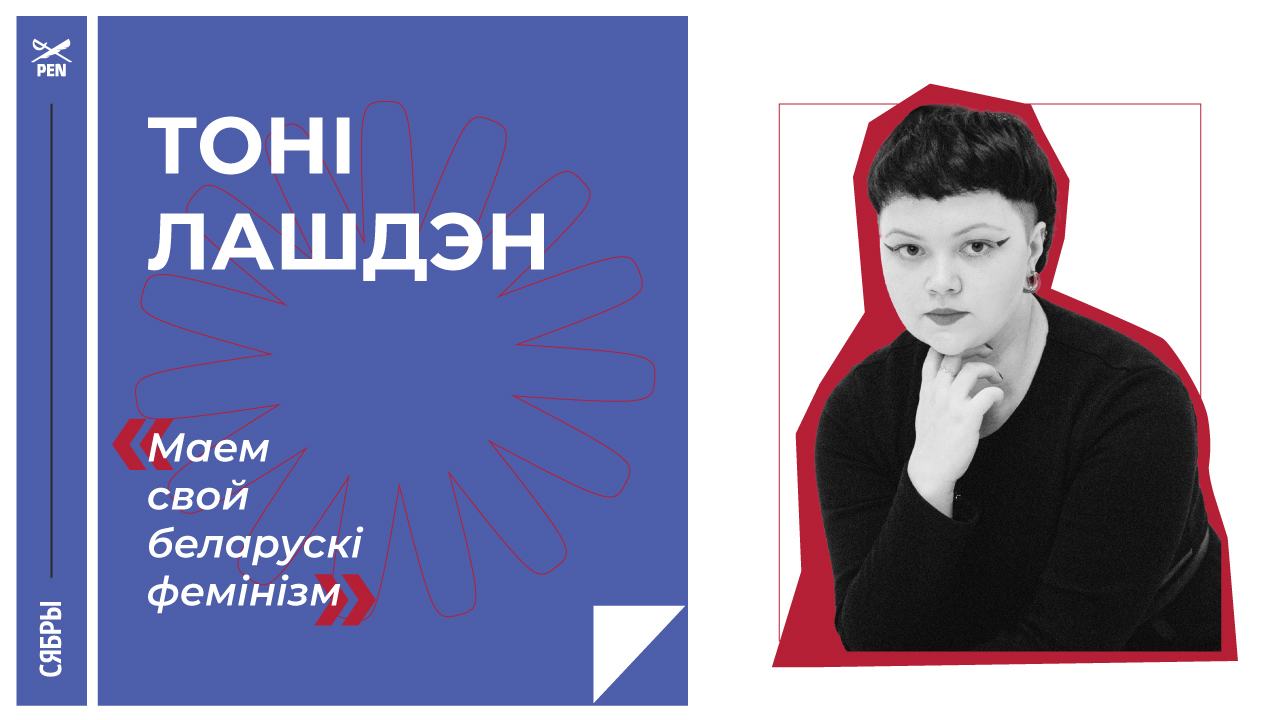

This conversation became an incredible opportunity to learn more about a cause that embodies struggle — for life, for freedom, for equality and peace. We are all somewhere nearby, yet not truly together. Each person’s role in this fight can become more meaningful if we start to notice and support one another. My interviewee, Tony Lashden, is a queer-fem writer, poet, and activist, and a member of PEN Belarus. I thank Tony for this thoughtful and important dialogue.

Everyone will leave,

And I, like the last fucked-up one, will stay

Clutching the switch

At the airport with blue fingersI’m not going anywhere

I’m not going

— Tony Lashden

Recently, during one of the literary events, you read your poem “Everyone will leave, I will stay.” You read it from the heart, as if those distant emotions were still fresh. How did such honest lines come to be?

It was 2020. I decided to stay in Minsk. At that time, I was sleeping only about three hours a night because there was so much human rights work to be done. And everyone was saying I had to leave. But I stayed in Minsk until the summer of 2021. It was an easy choice in the sense that I simply didn’t want to leave. I didn’t want to leave under pressure. That was my protest against a reality in which so many people were forced to abandon their homes. And when it finally became completely impossible to hold on to my life in Minsk, I moved to Kyiv.

Please tell us about the beginning of Tony Lashden’s path as an activist.

That’s a good question. I’ll begin the answer from today. I brought a small figurine of a dog to our meeting — his name is Eric. He belongs to Nasta Loika, who is now imprisoned under charges of “extremist activity.” Nasta is a close friend of mine. This year, as I’ve become more publicly visible, I’ve been taking Eric to all my interviews and events to speak about political prisoners who are currently behind bars — and, more broadly, about the difficult situation in Belarus.

My main activism now is more invisible: I create support services for people affected by various forms of violence, I work with feminist writing, and I advocate for women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. But 10 or 11 years ago, the context I worked in was very different, and so was my activism. In 2011, when I started studying at Belarusian State University, I became interested in gender studies. At the time — and still — gender studies did not officially exist as a scientific field in Belarus. Gender equality and feminism were deeply unpopular topics. Only about ten visible activists were involved in this work: Iryna Salamatsina, Iryna Alkhouka, Alena Autushka… We were separated by time and the themes we focused on. They were actively working on legal reform to support women — something that felt very distant to me at the time. I was more interested in spreading feminism and introducing it to my peers.

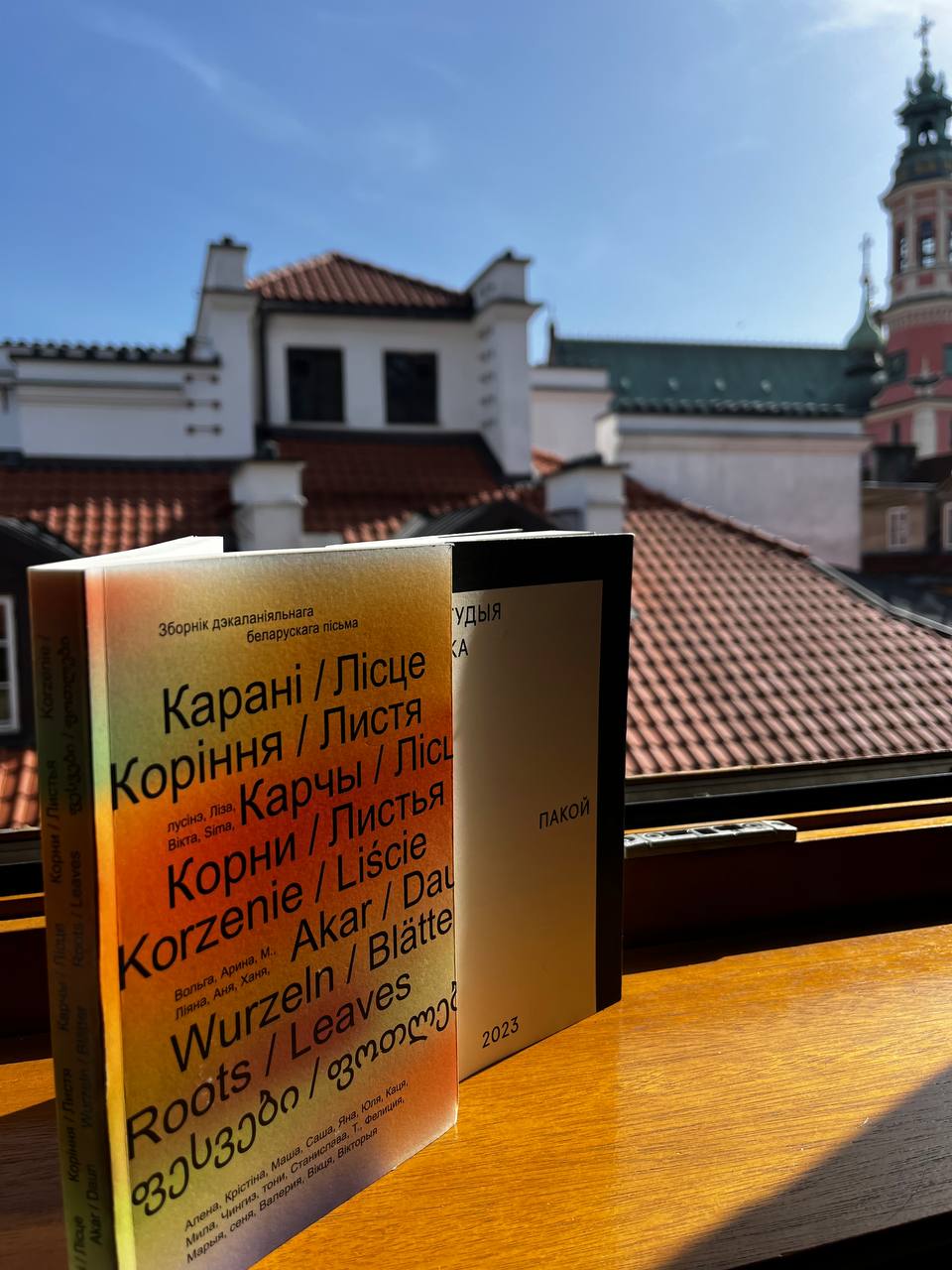

I translated a lot on feminist theory and gender studies. That’s how my activism began. If you want to learn — translate, search, study on your own! And to this day, making thematic literature more accessible remains an important part of my work. For instance, the most recent collection I worked on, “Roots / Leaves”, was made available in digital form and can be downloaded for free.

2011 marked the beginning of your activism. But what came before that? How did you imagine your path back in school — your profession, your life?

I really wanted to be a writer. But everywhere I turned, I heard that a writer’s life was marginal, that there’s no money in it. People kept saying that writing was just a hobby, and that you also needed to have some real skills. So I started writing as a journalist and worked that way for many years. In the end, I think getting a profession was very useful for me.

Now that I’m focused on literature, I do have financial support.

You lived and studied in several countries. In one interview, you spoke about your first experience of participating in a feminist march — 2015, Sweden. Why did you choose Sweden for your further studies?

At the Belarusian State University, my major included an exchange program that allowed us to spend a semester abroad. So I went to Sweden. At the time, Scandinavian life felt like a perfect fit for me: people respected each other’s personal boundaries, and gender equality — as well as equality for vulnerable groups — seemed to have been achieved. Sweden already had a Feminist Foreign Policy, which definitely contributed to the perception of the country as very progressive in these areas — especially compared to Belarus, where at my university I was told things like: “What gender stereotypes? Let’s write your thesis about how social advertising strengthens family values!” Abroad, I was just relieved I didn’t have to constantly prove something or explain myself.

Of course, later, when I returned there for my master’s degree, I began to see the cracks. In reality, Sweden has deeply embedded structures of xenophobia and racism. And interestingly, they’re maintained in similar ways to Belarus. For instance, Swedish society sees itself as highly tolerant, believing that racism has already been resolved. The same kind of narrative exists in Belarus, where there’s a constant emphasis on the country’s tolerance and openness. But in practice, it’s not true. People who face discrimination in Sweden’s migration system — and as a result experience poverty and homelessness — are in an incredibly vulnerable position. The longer I lived there, the harder it became to turn a blind eye or pretend it wasn’t happening.

Based on your experience living in Sweden, can you compare the life paths of Belarusian and Swedish women?

I’m a non-binary person, so my answer is primarily based on observing others. My personal experience in Belarus was that of growing up in a middle-class family with relatively stable finances. I was very lucky with where I lived in Minsk and with my social environment. There isn’t one single archetype of a Belarusian woman we can point to. People are extremely diverse. The same is true for women in Sweden.

But of course, there’s a fundamental difference between life in Sweden and life in Belarus. Take the feminist march, for example. I went there carrying a traumatic memory of participating in similar events before. I was seriously thinking: What will I do if I get arrested in Sweden? The march was completely surrounded by police — but they were doing their job: protecting the participants and ensuring their safety. There were lots of people — mothers with young children, men, the migrant community, LGBTQ+ folks. That day I felt just how different our lives are. People there will never truly understand what it’s like to feel physical fear when stepping into a march or protest.

What is the history of the feminist movement in Belarus? Can we say that it’s something new for our country?

In my view, no — we can’t say that. Belarus has had its own feminism clearly since the early 20th century. It’s crucial that we reclaim that history for ourselves. Public feminists in Belarus have always existed, and still do. And public visibility continues to be a serious risk for women. Today, we can see this with our own eyes: those who actively expressed their social and political positions ended up in horrific conditions, with the state threatening their children and parents. We don’t have to look far — there was already a strong feminist movement in Belarus in the 1990s. But in the 2010s, the historical continuity was broken because many people had to stop their work and flee to safer countries. A new wave of activists came to take their place. These broken intergenerational links between feminist activists in Belarus — that’s a real problem.

While studying gender at the European College of Liberal Arts in Minsk, I met one of its co-founders, and one of the country’s most well-known feminists — Iryna Salamatsina. She not only helped us understand gender topics but also introduced us to different feminist voices. That’s when I realized how many such women there actually were. Now, in exile, there are far fewer opportunities to build those connections. But the struggle continues — people like Volha Shparaha (a PEN Belarus member), Yulia Mitskevich, Volha Harbunova, Nasta Bazar, Ksiusha Malyukova and many others carry it forward. They all worked successfully in Belarus in the 2010s and early 2020s but were forced to leave.

Were the women’s protests of 2020 a feminist project?

I’d say they were important not so much for feminists specifically, but for Belarusian women in general. It was a women’s project. And why does that distinction matter to me? Because women joined the protests not through feminist beliefs, but in response to violence — against their loved ones and against society. That experience is extremely valuable for all of us. It proves our ability to unite around shared values: life, freedom, the rejection of violence. What mattered to me was that even if those women weren’t ready to call themselves feminists, we still stood side by side, we supported one another. That’s when I truly felt that there was a place for me in this country.

And the so-called Belarusian Women’s Union, which is currently very active and visible — is that feminism?

I don’t believe so. It really depends on how you define feminism. To me, feminism is a political perspective that recognizes the existence of a system called patriarchy, in which women are marginalized. Economically — they earn less for the same work; socially — they have fewer chances to hold powerful, influential positions or to speak publicly on important topics; culturally — their creative output is often seen as less valuable than that of men.

In Belarus, there are plenty of organizations that aren’t willing to talk about the existence of such a system or the discrimination it creates — they refuse to work with the roots of the problem. The organization in question has a pretty clear stance: they’re not interested in any of the above. Their narrative is centered entirely on the “woman-as-mother, woman-as-homemaker” idea.

And yet, if you look at global gender equality rankings, Belarus appears to be right up there with Sweden. It’s true — there are many women in parliament and in high-level positions… But do they really have power? It seems like they don’t. They don’t solve urgent problems in society. You can have a group of forty-nine women and one man, and yet that one man is the one making all the decisions. That’s exactly how it works in Belarus.

Let’s move to your creative work. Do you remember how it started? What inspired you in the very beginning?

My first writings were poems — and like most first poems, they were pretty bad. When I showed them to my parents, they laughed. That shame closed off poetry for me for many years. Sabina Brylo once said that her early works were “pure Akhmatova,” and mine were the same. I kept diaries, but I didn’t write publicly. I attended lots of literary events in Minsk.

One day, I walked into the Logvinov bookstore, which was near Victory Square at the time, and I saw a poetry collection by Nasta Mancevich titled “Birds.” That book changed my life. I thought: If there are lesbian poets in Belarus, then maybe not everything is lost for me either.

You also write prose. Your most recent book just came out. “black forest” — who is this book for?

It’s primarily for those who didn’t personally live through 2020, 2021, and 2022 — or for those who are searching for a language to speak about this painful experience. black forest is written in Russian, with occasional Belarusian passages. It’s accessible to readers who don’t speak Belarusian, and I’m deeply moved to see how it resonates with people in Central Asia, in the Caucasus, and among the Indigenous peoples of Russia. For them, it’s not just a book about linguistic blending or the integration of cultural and political experiences — it’s also about how to build strategies of resistance to Russian imperialism.

It’s worth noting that at the time of this interview’s publication, the Belarusian publishing house “Miane Nema” has released a print version of black forest.

The book is available for purchase through the Belarusian publisher Miane Nema.

If I may, I’d like to share some exciting news with our readers. We can officially confirm that Tony Lashden will be moderating the women’s panel during the Hučna Fest on the “Closer to You” literary stage, a program curated by PEN Belarus in collaboration with the Free Belarus Centre. The discussion will focus specifically on Belarusian women’s literature. With that in mind, here’s a question: are today’s Belarusian writers still capable of turning their creative work into manifestos, as their predecessors did in the last century?

I believe that to write a manifesto, we need a space where people can gather and talk about what truly matters to them. I don’t think the current absence of a manifesto is due to a lack of revolutionary voices capable of writing one. Look, for instance, at the community of women writers connected to Rastjazhenne — an archive of feminist writing, a collective of Belarusian authors who use literature to seek feminist alternatives within Belarusian culture and literature. That group includes around 50 incredibly talented and vibrant writers, scattered across the globe: Ukraine, Poland, New Zealand, Australia, Germany, and more.

A manifesto requires attentiveness and respect for each person’s views. As an activist, I can say that the best way to build this kind of work is to gather physically, to come together and ask what values we share as a community — to ask why we are here. And when that contact exists, it’s much easier to build mutual respect and understanding.

So I have a proposal: let’s organize writers’ camps! Let’s bring together young authors and poets. They won’t just write manifestos — they’ll come up with so much more. It’s no secret that young writers often lack resources. So this is my dream — addressed to the patrons and supporters of Belarusian literature.