“And this abrupt downfall:

today you are normal, respected, a role model, you are praised and given a diploma. And tomorrow, for something

you have done – you haven’t done anything wrong or violated anything,

but suddenly… – that’s it, you’re out of favor...”

From an interview with a Belarusian writer

About Monitoring

Main results

Deaths in prisons and confinement conditions for cultural figures

Criminal prosecution and trials of cultural figures

Administrative prosecution and detentions

Prosecution for donations

Violation of the right to freedom of movement

Persecution of cultural figures who fled the country

Dismissals and a ban on profession

Administrative obstacles, censorship and a ban on the dissemination of Belarusian culture

Pressure on civil society organisations in the cultural sector

“Extremist materials”

Attacks on historical and cultural heritage – national history objects and the Polish memorials

State policy in the sphere of culture

Conclusion and recommendations

Since October 2019, PEN Belarus has systematically documented the violations of cultural and human rights of cultural figures. This monitoring report contains statistics and analyses of violations that occurred in 2023. It summarises information collected from open sources, through personal contacts and in direct communication with cultural figures, including during the study on hidden repression[1]. We do not show the dynamics in the number of violations for 2020–2023 as data are not fully comparable due to the changes that violations and research methodology undergo to a greater or lesser extent. It is important to note that repressions in Belarus increasingly take non-public forms, and information about them goes into closed professional communities. PEN Belarus’ monitoring group is looking for alternative ways to collect information, and we thank every person who continues to share it. If you want to report wrongdoing (confidentially) or correct inaccuracies, please contact us at [email protected], telegram: @viadoma. The more accurately we can record and analyse the human rights situation in the cultural sphere, the more effectively we can plan our work to support artists and cultural projects.

NB: For users’ information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources if they are subject to restrictions under the current regulations in the Republic of Belarus.

MAIN RESULTS

The socio-political crisis in which Belarus found itself as a result of the regime’s falsification of the presidential election and subsequent violent crackdown on peaceful protests in 2020 continues to harm the cultural sphere. Politically motivated persecution of cultural figures, including those who have fled the country (searches, interrogations, detentions, administrative arrests, criminal sentences, property seizures) continues unabated. State media routinely publish defamatory materials. The cultural sphere is permeated with censorship and total control. Disloyal specialists are dismissed, and there is a ban on professional activities. The regime considers Nobel laureates, Belarusian culture popularisers, musical groups and works of literary classics as a threat to “national security”. Under the guise of the fight against extremism and terrorism, it deprives creative people of the opportunity to express themselves and earn a living; sometimes, they may even lose life.

Based on the situation in the cultural sphere in Belarus and the role of cultural workers in the country, as well as on the report of the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights on cultural rights defenders (2020), we recognise cultural workers in Belarus as cultural rights defenders.

- The 2023 monitoring recorded 1,499 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures, including:

-

- 1,097 violations against 605 cultural workers and persons whose cultural rights had been violated;

- 163 violations against 147 organisations and communities;

- 57 violations concerning historical and cultural heritage sites and the Belarusian language;

- 182 pages of cultural figures on social media or music videos, books, magazines, websites, YouTube channels and other culture-related materials were designated as “extremist materials” by Belarus’ Ministry of Information.

- As of 31 December 2023, at least[2] 155 cultural figures were behind bars or their liberty restricted otherwise. Human rights activists recognise 104 of them as political[3] prisoners. According to the Human Rights Centre “Viasna,” there were 1452 political prisoners in Belarus by the end of 2023. 10 cultural figures are in prisons; 80 are serving criminal sentences in penal colonies; 4 are in open-type correctional facilities; 21 are in pre-trial detention centres of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) and the State Security Committee (KGB) awaiting trial or transfer to the places of serving their sentences; 38 cultural figures are in home confinement[4]; the whereabouts of 2 more people is unknown to human rights defenders.

- Artist Ruslan Karčauli, cultural manager and blogger Mikalai Klimovič, artist and performer Aleś Puškin died in confinement.

- Cultural workers are subjected to inhuman treatment in confinement. The persecution does not stop even after the sentence has been served.

- At least 76 cultural figures and workers have been convicted of criminal charges, 245 since 2020.

- At least 206 cultural figures were arbitrarily detained. At least 79 people saw fresh criminal cases opened against them. At least 143 cultural figures were subjected to administrative prosecution.

- The most frequent violations against cultural figures were the violation of the right to a fair trial (306 cases) and arbitrary detentions (216). Administrative obstruction of activities, including forced liquidation (92) and censorship (66) were the most frequent violations against organisations and communities.

- The top 10 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures are as follows:

The number of recorded censorship cases, “extremist materials” and freedom of information violations increased significantly compared to 2022.

- The following forms of persecution should be noted:

-

- a complete information vacuum about high-profile political prisoners, including musician and public figure Maryja Kalesnikava, writer, bard and lawyer Maksim Znak, cultural manager and political figure Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, philanthropist and political figure Viktar Babaryka;

- a sentence against a cultural figure in the framework of special proceedings – former Culture Minister and exiled politician Paval Latuška was sentenced to 18 years in a penal colony in absentia;

- a sentence for “Belarusian nationalism” – cultural manager Paval Bielavus received a 13-year sentence for promoting Belarusian culture: organisation of concerts, literary meetings, lectures, popularisation of national symbols;

- inclusion of cultural figures in the “List of organisations, formations and self-employed entrepreneurs involved in extremist activities” as participants in these formations;

- persecution of cultural figures for donations to solidarity funds[5], later designated by the regime as “extremist formations”;

- more stringent checks at the border when returning to Belarus;

- politically motivated exclusions of artists from the Belarusian Union of Artists;

- labelling the works by the classics of the Belarusian literature of the 19th–20th centuries as “extremist materials.”

- The crackdown on dissent and freedom of expression takes place under the guise of a fight against extremism and terrorism.

-

- 10 cultural figures were included in the “List of organisations and individuals involved in terrorist activities” (as of today, it contains 28 cultural workers). 80 cultural figures were added to the “List of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, foreign citizens or stateless persons involved in extremist activities” (at least 188 cultural figures in total are on this list).

- The Tor Band music group, the Belarusian Association of Journalists, Radio Ranak, Štodzień Homiel and MOST media outlets (covering, among other things, the topics of the Belarusian language, history and culture) are on the “List of organisations, formations, self-employed entrepreneurs involved in extremist activities.”

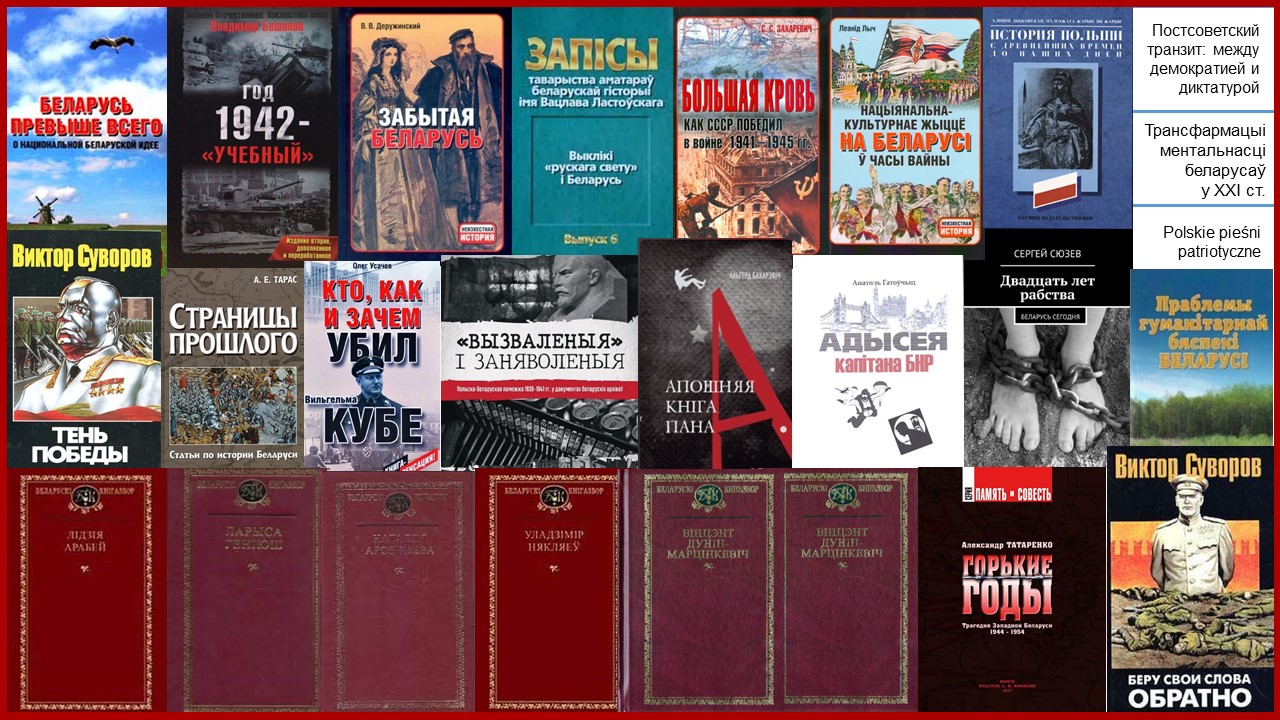

- At least 182 culture-related materials or social media accounts of cultural figures are included in the “List of Extremist Materials.” Like never before, some book chapters were labelled as “extremist.” Since 2021, 37 books, two poems and one preface to a publication were included in this list.

- Politically motivated dismissals and the practice of “banning the profession” continue.

- Political and ideological censorship make it more challenging to create and disseminate the Belarusian culture:

-

- The “blacklists” and lists of “unreliable” cultural figures are expanding.

- Administrative obstacles are created for concerts, exhibitions, meetings, hobby clubs and other events. The government continues to control the repertoires of theatres, cinemas and museum expositions.

- The independent Belarusian publishing houses Januškievič, Knihazbor and Zmicier Kolas were liquidated.

- 45 non-profit organisations from various fields of the cultural sector, mainly those working with the protection of historical and cultural heritage, preservation of historical memory and national minorities, were forcibly liquidated. Since the beginning of the targeted campaign to cleanse the civil society in Belarus (the end of 2020), at least 228 non-profit organisations related to the cultural sector of Belarus have undergone forced liquidation.

- The regime fights against “unnecessary” memory – the national history and Polish memorial heritage.

- There have been new cases of harassment of participants in cultural events.

- The state policy in the cultural sphere is characterised by tightened control, legalization of discrimination, de-legalisation of the independent cultural sphere, ideologisation, militarisation, sovietisation and patriotisation. Emphasis is put on anti-Belarusian, anti-Western, anti-Ukrainian, and pro-Russian vectors of the state policy. Persecution for the use of Belarusian national symbols, publications on national history, and discrimination against the Belarusian language continue. Defamatory materials, statements and hate speech characterize the state media propaganda.

DEATHS IN PRISONS AND CONFINEMENT CONDITIONS FOR CULTURAL FIGURES

On 5 January 2023, artist Ruslan Karčauli died in a Hrodna prison. According to the information received, the death occurred after suffering from pneumonia due to untimely medical care.

On 6 May, cultural manager and blogger Mikalaj Klimovič, a 61-year-old political prisoner with a Class 2 heart disability, was sentenced on 28 February to one year in a penal colony for posting the “Funny” emoticon under a satirical image of Lukašenka in the Odnoklassniki social network, died in a Viciebsk colony.

On the night of 11 July, political prisoner artist and a human legend of performance art Aleś Puškin, sentenced to five years in prison for his 2014 portrait of the anti-Soviet guerilla fighter Jaŭhien Žychar, died in intensive care due to inadequate medical care for neglected ulcer perforation. Aleś Puškin served his sentence in a Hrodna prison.

On 1 June, poet Dzmitry Sarokin died in the building of the Lida district police department under unclear circumstances; we have no details about the incident.

Human rights activists and members of the public attribute these tragic deaths to the conditions of confinement and inadequate medical care in closed institutions of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) system.

The farewell rituals for Mikalaj Klimovič (in May) and Aleś Puškin (in July) took place under the supervision of plainclothes “law enforcement” officers, who recorded on camera those who came to say goodbye. The relatives, friends and colleagues were strongly advised to refrain from comments and interviews.

***

The regime also persecutes dissidents in places of confinement by placing cultural figures on preventive registers, imposing administrative penalties for spurious reasons, transferring them to solitary confinement, punitive isolation, punishment cells, and cell-type premises. In 2023, these measures were applied at least to Uladzimir Mackievič, Aleś Papkovič, Maryia Kalesnikava, Paval Sieviaryniec, Viktar Babaryka, Andrej Pačobut, Uladzimir Hundar, Ivan Viarbicki, Paval Vinahradaŭ, Aliaksandr Franckievič);

strengthening the confinement regime: the transfer from a penal colony to prison was applied in 2023 to Uladzimir Mackievič, Dzmitry Kubaraŭ, Paval Sieviaryniec, Uladzimir Hundar, Paval Vinahradaŭ; on 4 August, a trial on changing the confinement regime for Vadzim Hulevič was scheduled but the outcome remains unknown; restriction of freedom in an open-type correctional facility was replaced with a penal colony for Hleb Kaipiš); home confinement was replaced with a penal colony for Barys Kučynski;

initiation of new criminal cases for “malicious disobedience to the demands of the administration of a penitentiary institution” (Article 411 of the Criminal Code) (Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, Alena Hnauk, Dzmitry Daškievič);

deprivation of parcels and packages, calls and visits by relatives and lawyers, restrictions on walks, sports and communication with other prisoners, interrogation summons, cell searches, etc.

In 2023, the practice of incommunicado – complete isolation of the convicted person from the outside world (blocked correspondence, banned calls and visits by relatives and lawyers) – was applied to some political prisoners. Since February 2023, the relatives of Maryia Kalesnikava and Maksim Znak have not heard anything about the whereabouts and condition of their loved ones. Since March 2023, there has been no independent information about Siarhiej Cichanoŭski. Since April, there has been no communication and information about the health of Viktar Babaryka, who was hospitalised in late April in a life-threatening condition. There has been no official information from the state authorities, the Department of Corrections, or the prosecutor’s office about what happened to him, where he is, and in what condition.

Blocked correspondence and prevention of prisoners from having a lawyer present becomes an ordeal for both political prisoners and their families, who, for extended periods, may be completely unaware of what is happening to their loved ones. “Without finding out what condition he is in, I feel powerless. I often mentally correspond and imagine what he might have said to me. The lack of communication is torture,” a relative of one of the political prisoners told us. Belarusian human rights activists have repeatedly noted that the deprivation of correspondence falls under the category of torture, which is considered a crime against humanity and has no statute of limitations.

Harassment and psychological pressure do not end even when people leave prison. This practice has become widespread concerning those who fully served their sentences and those sentenced to home confinement. Constant changes in the conditions of confinement, checks at any time of the day or night, free time limitations, insults, intimidation, provocations and far-fetched violations of the confinement regime, followed by administrative arrest, are only part of the pressure campaign.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION AND TRIALS OF CULTURAL FIGURES

Since the start of monitoring in October 2019 and the largest protests against Lukašenka’s authoritarian regime in the history of Belarus in the summer of 2020 – winter of 2021, no less than 52 cultural figures have walked out free, having fully served their criminal sentences – 1-3 years in a penal colony, 1.5-3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility or 1-2 years of home confinement. However, new people of creative professions came into their place, and arbitrary detentions, arrests, and subsequent trials continued in 2023. People were detained and tried for participating in peaceful rallies in 202 and making public statements about any topics and events that resonated with the state, for donations and creativity. They were deprived of the right to the freedom of information and association. In most cases, the authorities disguised their unlawful rulings as a fight against extremism and terrorism. Courts, in such cases, are only a tool to crack down on dissent.

In 2023, new criminal cases were opened against at least 79 cultural figures who remained in Belarus or fled the country. No less than 76 cultural workers were sentenced to between one and 18 years of imprisonment. Many professionals were sentenced to lengthy terms. Cultural manager, founder of the independent cultural platform Art Siadziba and the shop of national symbols Symbal.by, a consistent populariser of Belarusian national culture Paval Bielavus was detained in November 2021 and charged with state treason (Art. 356), calls for actions aimed at harming the national security of the Republic of Belarus (Art. 361), creation of an extremist formation[6] (Art. 361-1), as well as organisation and preparation of actions that grossly violate public order or active participation in them (Art. 342) ” “under the guise of cultural and historical development… he spread the ideas of Belarusian nationalism“, as the prosecution stated. On 11 May 2023, Paval Bielavus was sentenced behind closed doors to 13 years in a medium-security penal colony[7] and a fine of 18,500 BYN.

Aleś Bialiacki, the writer, chairman and founder of the Human Rights Centre “Viasna”, the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, was detained in July 2021 for his human rights activities and assistance to the victims of repression. He was charged with smuggling – illegally transferring funds on a large scale (Art. 228) and financing the group actions that grossly violated public order (Part 2 of Art. 342). On 3 March 2023, a court sentenced Ales Bialiacki to 10 years in a medium-security penal colony and a fine of 185,000 BYN.

Political scientist, publicist, founder and editor of the expert community website Our Opinion, the editor of the Belarusian Yearbook annual collection of analytical reviews of the situation in Belarus, Valeryja Kasciuhova was detained at the end of June 2021 and accused by the regime of calling for actions aimed at harming the national security of the Republic of Belarus (Article 361), conspiracy to seize power by unconstitutional means (Article 357), incitement of hostility or discord (Article 130). On 17 March 2023, a court sentenced her in a closed-door trial to 10 years in a penal colony.

Musician Jaŭhien Hluškoŭ was detained in August 2022 when police were checking the phones of residents in connection with the incident at Ziabroŭka (a military airfield in Homiel region, where Russian troops had been stationed since the beginning of the war with Ukraine and from where Russian forces launched missiles on the territory of Ukraine). For the photos of the airfield found in his phone, he was charged with state treason (Art. 356) and promotion of extremist activity (Art. 361-4). On 20 January 2023, Jaŭhien Hluškoŭ was sentenced behind closed doors to 9 years in a medium-security penal colony.

Members of Tor Band, a music band from Rahačoŭ, Jaŭhien Burlo, Dzmitry Halavač and Andrej Jaremčyk, whose songs became the symbols of Belarusian protests, were detained in October 2022. In November, it became known that 10 songs, YouTube channels, Patreon, and the band’s social networks were included in the “extremist materials” (designated by a court ruling on 29 August 2022). In January 2023, 2.5 months after the musicians’ detention, the KGB designated Tor Band as a” “extremist formation.” The musicians were charged with inciting social hatred (Article 130), creating an extremist formation (Article 361-1), discrediting Belarus (Article 369-1), and insulting Aliaksandr Lukašenka (Article 368). On 31 October 2023, in a trial behind closed doors, a local court sentenced vocalist and songwriter Dzmitry Halavač to 9 years, drummer Jaŭhien Burlo – to 8 years, bass-guitarist Andrej Jaremčyk – to 7.5 years in a medium-security penal colony and a fine of 3,700 BYN each.

Andrej Pačobut (Andrzej Poczobut), a journalist, essayist, and member of the Union of Poles of Belarus, who spoke about the Belarusian protests of 2020, historical events of 1939 and defended the Polish minority in Belarus, was detained in March 2021 as part of a crackdown on the Polish minority activists. The regime charged him with calling for actions aimed at harming the national security of the Republic of Belarus (Art. 361), inciting hatred or discord (Art. 130). On 8 February 2023, Andrej Pačobut was sentenced to eight years in a medium-security penal colony behind closed doors.

Eduard Babaryka, cultural manager, entrepreneur and head of the nomination group for presidential candidate Viktar Babaryka, was detained together with his father in June 2020. Detained for over three years, he was eventually charged with organising and preparing actions that grossly violate public order or actively participating in them (Art. 342), tax evasion (Art. 243), and inciting hatred or discord (Art. 130). On 5 July 2023, Eduard Babaryka was sentenced to eight years in a medium-security penal colony.

Ruslan Labanok, the founder of the Spanish visa centre, and Vaclaŭ Areška, a cultural critic, archivist and activist of the REP independent trade union, were sentenced in 2023 to 11 and 8 years in a medium-security penal colony, respectively. Their trials were held behind closed doors.

44 cultural figures were punished with a penal colony. The researcher and moderator of the “For the Single State Language in Belarus!” group on the VKontakte social networking platform, Uladzimir Butkaviec, was sent to an open-type correctional institution instead of a colony due to the appeal. 31 people were sentenced to home confinement. The outcome of one trial remains unknown to us.

In 2023, the following people were convicted:

January: Vaclaŭ Areška, cultural critic, archivist, activist of the REP independent trade union (8 years in a medium-security penal colony); Aliaksandr Lyčaŭka, local historian and journalist (3 years in home confinement); Valeryja Čarnamorcava, tour guide and researcher (2.5 years in home confinement); musician Jaŭhien Hluškoŭ (9 years in a medium-security penal colony); singer Mieryjem Hierasimienka (3 years in home confinement); Banki-Butylki bar owner Andrej Žuk (2.5 years in home confinement).

February: videographer and musician Hleb Hladkoŭski (5 years in a penal colony); actor and casting director Viktar Bojka (3 years in home confinement); illustrator Vadzim Bahryj (penal colony, the term is unknown); history teacher Siarhiej Koziel (3 years in home confinement); poet, musician, journalist Andrej Pačobut (8 years in a medium-security colony); researcher and moderator of the “For the Single State Language in Belarus!” group on the VKontakte social networking platform Uladzimir Butkaviec (3 years in a medium-security penal colony); architect Valeryja Sokal (2.5 years in home confinement); cultural manager, video blogger and politician Siarhiej Cichanoŭski (retrial: additional 1.5 years in a medium-security penal colony to the initial sentence of 18 years in a penal colony); cultural manager and blogger Mikalaj Klimovič (1 year in a penal colony).

March: literary scholar, researcher of the history of Belarusian literature, essayist and human rights activist Aleś Bialiacki (10 years in a medium-security penal colony); director of the event agency KRONA Siarhiej Hun (penal colony, term unknown); cultural manager, Minister of Culture of the Republic of Belarus in 2009-2012, politician Paval Latuška (18 years in a penal colony, convicted in absentia); founder of the Spanish visa centre Ruslan Labanok (11 years in a medium-securty penal colony); philologist and Italian language specialist Natallia Dulina (3.5 years in a penal colony); musicians Dzmitry and Uladzimir Karakin (2.5 years in home confinement each); culture and etiquette expert Aksana Zareckaja (1.5 years in a penal colony); author and editor, political scientist and analyst Valeryja Kasciuhova (10 years in a penal colony); post-graduate student at the History Faculty of Belarusian State University Yury Ulasiuk (3 years in home confinement); photographer and journalist Hienadź Mažejka (3 years in a penal colony); writer and bard Aliaksiej Iljinčyk (2.5 years in a penal colony); photographer Varvara Miadźviedzieva (2.5 years in home confinement).

April: local historian and activist Uladzimir Hundar (third sentence: 2.5 more years in a medium-security penal colony in addition to the initial 18 years – 20 years as a result of the partial addition of sentences); actor Andrei Tryzubaŭ (3 years in home confinement); German language teacher, local historian and bachelor of theology Andrej Pukanaŭ (2 years in a penal colony); musicians Andrej and Vera Mamojka (2.5 years in home confinement each); singer Aliaksandra Zacharyk (3 years in home confinement); writer and activist Alena Hnaŭk (fourth sentence: one more year in a penal colony in addition to the initial sentence of 3.5 years); author of articles for Wikipedia Ivan Marozaŭ (1.5 years in a penal colony); children’s writer and teacher Dzmitry Jurtajeŭ (2 years in a penal colony).

May: administrator of the Telegram channel “Pa-Bielarusku” and programmer Andrej Filipčyk (home confinement, term unknown); artist Hienadź Drazdoŭ (3 years in a penal colony); cultural project manager Paval Bielavus (13 years in a medium-security colony); designer Marharyta Sokal (3 years in home confinement); cultural manager and sociologist Yury Bubnoŭ (2 years in a penal colony); cultural manager and activist Uladzimir Bulaŭski (2 years in a penal colony); local historian and journalist Yaŭhien Merkis (4 years in a medium-security penal colony); literary scholar Jana Cehla (2 years in home confinement).

June: Academy of Arts student Darja Iksanava (2.5 years in home confinement); cultural activist Andrej Prymaka (4 years in a penal colony).

July: Andrej Niesciarovič, owner of the Cudoŭnia ethno shop (sentence unknown); cultural manager and entrepreneur Eduard Babaryka (8 years in medium-security penal colony); designer and tattoo master Illa Akišaŭ (home confinement, term unknown); architect Mikita Kavalenka (2 years in home confinement); singing coach Ladaryja Kuzniacova (one year in home confinement); poet, musician and translator Mikita Najdzionaŭ (3 years in home confinement); writer, photographer and journalist Dzmitry Bajarovič (3 years in home confinement); cultural manager Paval Mažejka (6 years in a medium-security penal colony); professor at the Department of Foreign Literature, Moscow State Linguistic University Natallia Žloba (3 years in a penal colony).

August: singer Patricyja Svicina (2.5 years in home confinement); violinist Natallia Bogush (2.5 years of home confinement); craftswoman Natallia Bielaja (2.5 years in home confinement); historical archive employee Natallia Piatrovič (6 years in a penal colony); urbanist, geographer Hanna Skryhan (2 years in a penal colony); local historian, documentary filmmaker, journalist Larysa Ščyrakova (3.5 years in a penal colony).

September: musician and IT specialist Aliaksiej Kuźmin (7 years in a medium-security penal colony); dancer and entrepreneur Viktoryja Haŭrylina (3 years and three months in a penal colony); Russian language teacher and journalist Tacciana Pytko (3 years in a penal colony)[8].

October: Russian language and literature teacher Ala Zujeva (2.5 years in a penal colony); translator from Spanish, Portuguese and English Vasil Krez (2 years in home confinement); translator from Chinese Kaciaryna Bruchanava (2.5 years in a penal colony); publicist and activist Dzmitry Daškievič (second sentence: one more year in a high-security penal colony after serving the initial sentence of 1.5 years in a penal colony); musician Jaŭhien Burlo (8 years in a medium-security penal colony); musician and author of lyrics Dzmitry Halavač (9 years in a medium-security penal colony); musician Andrej Jaremčyk (7.5 years in a medium-security penal colony); writer, PhD in Philology Nadzieja Staravojtava (3 years in home confinement); writer, PhD in Philology Natallia Sivickaja (3 years in home confinement).

November: founder and editor-in-chief of Rehijanalnaja Hazieta Aliaksandr Mancevič (4 years in a penal colony).

December: choir soloist Kaciaryna Cevan (2 years in home confinement).

In 2023, as in 2021-2022, cultural figures were most often convicted for participating in the 2020 peaceful protests – under Article 342 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (Organising and preparing actions that grossly violate public order or actively participating in them). At least 39 cultural workers were convicted under this provision. Cultural manager and activist Uladzimir Bulaŭski was convicted under Article 342-2 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (Repeated violation of the procedure to organise or hold mass events).

Between November 2020 and the end of 2023, at least 245 cultural figures were convicted under the Criminal Code, 11 of them two or more times. During the three years, the most common reason for prosecution was participation in peaceful protests in 2020 (Art. 342). The specifics of 2022 were an increase in the number of criminal convictions for “creating an extremist formation or participating in it” (Art. 361-1) and under defamation articles (Art. 368, 369). In 2023, the most common charge was “facilitating an extremist activity” (Art. 361-4). The regime treats cooperation with independent media, providing them with up-to-date information and administering chat rooms on social networks as extremism.

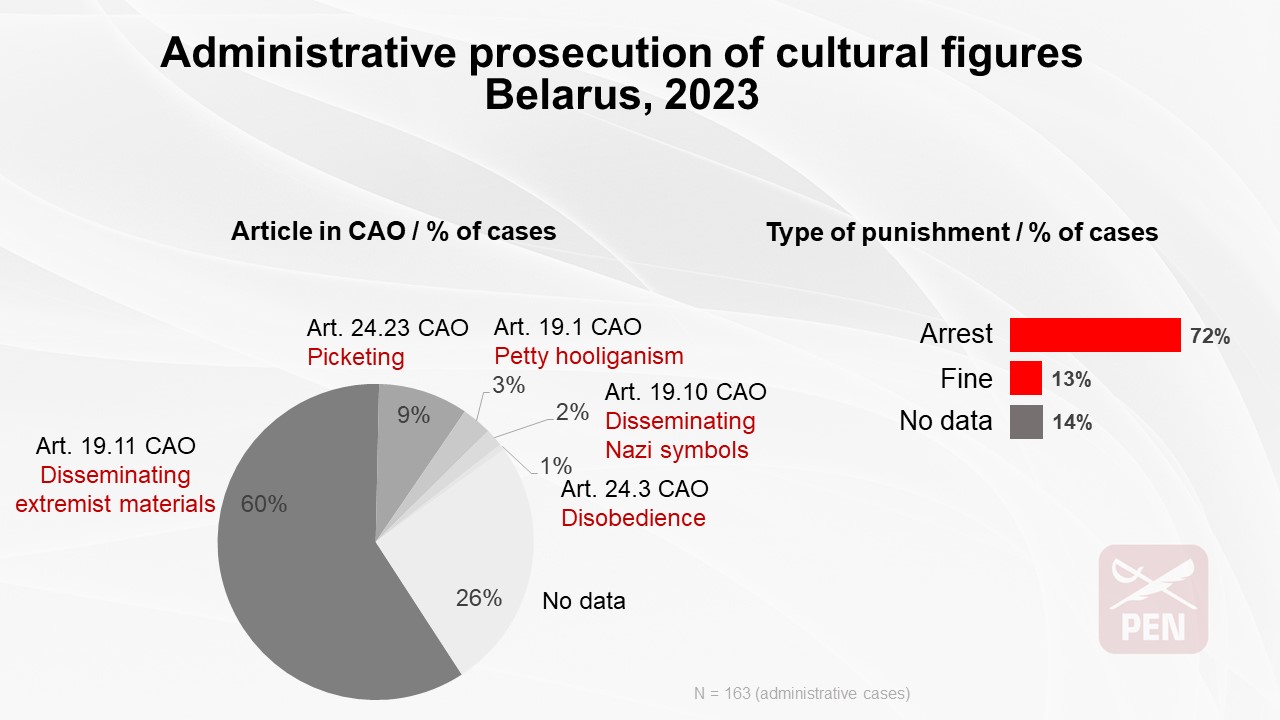

ADMINISTRATIVE PROSECUTION AND DETENTIONS

In 2023, 143 cultural figures were subjected to administrative prosecution (163 offence reports) for subscribing, liking, commenting or sharing the publications of exiled independent media on social networks. Most cases fell under Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences, which deals with “distribution, production, storage, transportation of information products containing calls to extremist activities or promoting such activities.” Belarusian courts did not care if the media outlets had been designated “extremist” during an interaction. Neither did it matter that their materials were not “extremist” – articles and videos with political, informational or cultural content, logos of independent media, etc.

There were cases when cultural figures faced administrative responsibility under Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences as a result of the police monitoring their social network profiles”(“in the course of carrying out a set of measures on the Internet”). It also happens due to the inspection of phones – a procedure that has become, in many respects, a parable of our time and the everyday life of Belarusians. Special services agents check the content of subscriptions on social media, personal correspondence and contacts when people of culture cross the Belarusian border. They also check the phones of students and lecturers at educational institutions during individual or mass detentions of employees with cultural and educational institutions either at work or home.

On 29-30 March, at least eight National Polack Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve employees were detained. Approximately the same number of professionals were arrested on 29 April at the Viciebsk State Technological University. At least four state-owned radio station Gomel FM employees were detained on 5 May. About fifteen employees of the Polack State University were detained on 23 May. At least seven specialists of the National Historical Archive of Belarus were arrested on 16 August. Seven employees of the Braslaŭ Museum of Traditional Culture were detained on the night of 21 to 22 December. Among the detainees were many representatives of our target group, most of whom were eventually punished in administrative proceedings for allegedly distributing extremist materials.

A total of 216 arbitrary detentions were recorded concerning 206 cultural figures.

PROSECUTION FOR DONATIONS

August 2020 was the time of the highest peaceful protest upsurge and an unprecedented[9] wave of solidarity. It was expressed, among other things, in lightning-fast collections of funds to help the victims of police violence. Belarusians, including Belarusian cultural figures, actively donated small and large sums to BYSOL, By_help and other solidarity funds using the Facebook payment system. 2023 is the year of criminal cases opened “based on the facts of providing money or other property for knowingly facilitating the extremist activity of extremist formations BY_help, BYSOL.”[10]

Donations were primarily made in 2020. The regime designated BYSOL and By_help as “extremist formations” in December 2021 and the Honest People and Country for Life initiatives – in February and November 2022, respectively.

The monitors recorded the first cases of persecution of cultural figures for their donations in April 2023. The regime has developed the following pressure scheme: to avoid a criminal case, it requires “active repentance,” i.e. signing a confession of guilt and X-fold compensation – a supposedly voluntary donation to an account proposed by the investigator. Many people are forced to agree to these conditions. At the same time, there were cases of criminal liability for donations. For example, on 6 October 2023, senior lecturer of the Foreign Literature Department at Minsk Linguistic University Natallia Žloba was sentenced to three years in a penal colony under the same article 361-2 of the Criminal Code (Financing the activities of an extremist group). On 18 September 2023, dancer and businesswoman Viktoryja Haŭrylina was sentenced to three years and three months in a penal colony under a combination of three articles of the Criminal Code). On 6 December 2023, former English teacher Iryna Abdukeryna received four years in a penal colony on a combination of four criminal charges. Belarusian human rights defenders stress that prosecution for donating to organisations not labelled as extremist (or terrorist) at the time of donation violates the law.

VIOLATION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT

Questioning at border checkpoints while crossing the Republic of Belarus state border became standard in 2023. An exhaustive search at the border of all cultural workers who went through administrative courts during and after the 2020 events has a recurring character. It happened on every foreign trip. For many, it has become a standard procedure and a new reality. However, in 2023, the situation took a turn for the worse. Sometime in May, a significantly more comprehensive range of people began to send reports about forced “conversations” with law enforcement officials and phone checks at border controls. The “conversation” is usually conducted by two special service agents. One checks the contents of a mobile phone – photos, subscriptions, browser history, and personal messages. The other asks questions:

- Where are you travelling from, and where are you going? What was the purpose of travelling abroad? Who did you meet, and what issues did you discuss?

- Where do you work? What is your source of income in Belarus? Marital status? Where and with whom do you live in Belarus?

- Do you have relatives abroad? And in Ukraine?

- Were there any problems with the law? Active in 2020, participation in yard chats, donations to funds, etc.?

- Why do you think you’re on our radar?

- Clarifying questions about the phone’s contents (from the agent who examined the phone).

We consider such treatment of cultural figures as a violation of the right to freedom of movement. It also includes banning them from leaving Belarus after their release from prison. In other situations, the exit of cultural figures is restricted, or they are refused entry into the country.

PERSECUTION OF CULTURAL WORKERS WHO FLED THE COUNTRY

The persecution of cultural workers who were forced to leave Belarus and carry out their activities from abroad continues.

- Defamation and discrediting in the state media are the practices that started back in 2020. The writer and Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Svetlana Alexievich, publisher of Belarusian literature Andrej Januškievič, opera singer Marharyta Liaŭčuk, the former director of the Kupala Theatre, ex-Minister of Culture of the Republic of Belarus Paval Latuška, and many other cultural figures, masters of their craft, specialists of the highest qualification and worthy Belarusians “re “washed” by propagandists in TV broadcasts, press, social networks – insultingly, rudely, contemptuously, nastily and with impunity.

- The initiation of criminal cases, searches at the place of residence, smashing of flats, seizure of property (houses, flats, equipment), use of special proceedings, and international wanted list are the forms of persecution and pressure that the regime has actively employed since 2021. In 2023, cultural figures were involved in criminal cases individually and when charged as a group of people. In November, it became known about fresh charges against cultural manager and former political prisoner Illa Mironaŭ, who left Belarus in June 2023. Writer, journalist and human rights defender Uladzimir Chilmanovič left the country 2.5 years ago. His flat was seized and searched in November; the furniture and household appliances were listed, and books, discs and many personal belongings were confiscated. When security agents visited his parents, writer Sasha Filipenko learned about the criminal cases opened against him. After the 29 July 2023 12-hour marathon “We are not all alone” to raise funds to support political prisoners, it became known in October that the Investigative Committee initiated a criminal case under part 2 of article 361-2 (financing of extremist activity) against about 60 people (“among the organisers and their accomplices“, as it is said in the IC report). It is known that they included musician and journalist Kaciaryna Pytleva, philologist and journalist Siarhiej Padsasonny (who has been living in Poland since 2008), and other participants in the charity marathon. On 28 November, a series of searches and property seizures occurred concerning the criminal proceedings over the attempted seizure of power against members of the Coordinating Council[11] – more than 100 people, according to the data from the Investigative Committee. Among them are many representatives of our target audience: cultural manager and politician Paval Latuška, historian Paval Cieraškovič and others. It was also reported that a procedure of special proceedings against the “defendants” of the case was being prepared. The practice, approved in July 2022, allows the trial of Belarusians disloyal to the regime and outside the country in absentia. In parallel with the wave of searches and seizure of real estate, there were threats to confiscate the flat of Svetlana Alexievich, a member of the Presidium of the Coordinating Council and a laureate of the Nobel Prize in literature.

- The pressure on relatives and visits of security agents to the places of residence of cultural figures who have left Belarus continues. In March, criminal investigation officers came to question the parents of opera singer Marharyta Liaŭčuk. They had already been detained in May 2022 and fined under an administrative offence report. In November, seven people with automatic rifles searched the flat of Sasha Filipenko’s parents. He is a writer and outspoken critic of the situation in Belarus in the European press. “They took the father away and told my mother: Say thank you to the “on,” Filipenko wrote on his Facebook page at the time. They seized the equipment but did not present a search warrant or a confiscation protocol. As a result, the father spent 13 days in a detention centre technically for reposting an article from “an “extremist channel.” In reality, he was punished for his son’s public statements. There were other cases of police searching for cultural figures living outside Belarus, visits of security officers to the relatives with threats and detentions, “inspections” of flats and searches. Another form of pressure is sending letters to the relatives from the Commission on Return, established under the Prosecutor General’s Office and operational since the beginning of 2023. Relatives of political migrants receive letters urging those who left to turn to the commission with a confession, describe the reasons for leaving the country and possible reasons for administrative or criminal prosecution, repent sincerely and declare their desire to return to Belarus. In practice, it is known that compliance with all the requirements of the commission does not guarantee that a person will remain free.

- Designating the statements of cultural figures on social networks as “extremist”. In 2023, the Ministry of Information’s list of labelling the personal social media pages of cultural figures in exile as “extremist” grew exponentially. The social media profiles of local historian and journalist Ruslan Kulevič, musician and activist Andrej Pavuk, musician and journalist Kaciaryna Pytliova, writer, art historian and politician Zianon Pazniak, musician and journalist Ihar Palynski, musician Andrej Ciapin, poet and media activist Valer Rusielik, singer Marharyta Liaŭčuk, writer and journalist Sieviaryn Kviatkoŭski, director and artistic director of the Free Theatre Mikalaj Chalezin, poet and translator Andrej Chadanovič, musician Liavon Volski and others were recognized as “extremist.”

DISMISSALS AND A BAN ON PROFESSION

Politically motivated dismissals of “he “unreliable” continue day after day. The scale can hardly be assessed fully, as the further we get from 2020, the less cultural figures publicly report being deprived of their jobs. However, even the publicised facts confirm that the “purges” in the system as part of the state policy in the cultural sphere do not stop. In February 2023, speaking at the board of the Ministry of Culture meeting on the work results in 2022, Culture Minister Anatol Markievič reported on the rejuvenation of the staff. It was due to the hiring of yesterday’s graduates of educational institutions in place of the dismissed “unreliable” specialists. The official also outlined a prospect for 2023, stressing that “traitors have no place on stage, whether it’s a state-sponsored special event or a concert in a rural settlement.” Artists willing to work for the state should either publicly repent of dissent or leave the cultural sphere forever. One of the disastrous consequences of such dismissals is the shortage of specialists and the de-professionalisation of the state cultural sector. It is often the best, most experienced and engaged workers who are affected by the crackdown.

This monitoring data contains information about 85 dismissals for political reasons in 2023. Early in the year, it became known that the authorities began purges at the Zair Azgur Memorial Museum-Workshop because of “destructive” cultural workers. On 1 February, director Aksana Bahdanava lost her position. During the 19 years of her leadership, the museum succeeded as a modern art platform. Several specialists were fired after the force raid, detentions and administrative arrests of Polack Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve employees. Among them were PhD Ihar Bortnik and PhD in Cultural Studies Tamara Džumantajeva, who in 2021 was awarded the sign “For Contribution to the Development of Belarusian Culture” and “Person of the Year in Viciebsk Region “014” in the Culture, Art, Spiritual Revival nomination from the Ministry of Culture. In December, it was reported about the non-renewal of the contract with the director of the Vetki Museum of Old Believers, Piotr Calko. During the year, the Belarusian State Puppet Theatre lost the talented theatre designer Liudmila Skitovič, one of the leading actresses Sviatlana Cimochina, the legendary director and one of the founders of the Belarusian puppet theatre Aliaksiej Leliaŭski. It is known about dismissals in 2023 from the Bolshoi Theatre of Belarus, Jakub Kolas National Academic Drama Theatre, Belarusian State Philharmonic Society, National Historical Archive of Belarus, Institute of Philosophy and Institute of Linguistics of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, National Film Studio “Belarusfilm”, Belarusian State Academy of Arts, Polack, Homiel and Belarusian State Universities, Lyceum of Belarusian State University, state archives, literary publications and other institutions of culture and education.

Employees’ loyalty at state institutions is under the control of HR officers, who are assisted by specially introduced ideologues as deputy directors in charge of “ideological work and security.” The head of the institution also plays an essential role in the issues of “personnel security in the area of work entrusted to him.” That’s why former law enforcement officers are often appointed as new top managers of various cultural institutions. The reasons for dismissal (technically more often formalized as “by agreement of the parties”) or non-renewal of the contract are the facts of detention, administrative arrest, criminal prosecution, donations to funds later designated by the regime as “extremist,” statements on social media and earlier statements made in the professional sphere, denunciations (including of colleagues), defamatory publications against cultural figures, refusals to join trade unions, as well as other reasons (sometimes not evident to the victim). In 2021, the dismissal of an employee on the employer’s initiative was justified by the following paragraph: “absence from work in connection with serving an administrative punishment in the form of administrative arrest.” Dismissal from a state institution for one of these reasons gives the specialist what is called in Belarus a “wolf’s ticket.” It means that any other state institution in the country is banned from employing such a person (rare exceptions are known). This procedure was legalised by the introduction in October 2021 of the practice of providing a character reference from the previous place of work, which should reflect the professional, business and moral qualities of the employee, information about their compliance with labour and executive discipline, attitude towards state and public institutions. The state establishes liability for providing characteristics containing knowingly unreliable information. The HR specialists bear responsibility for failing to filter out a “wrong” staffer.

Politically motivated dismissals and professionals’ problems with subsequent employment are repressive actions on the part of the state, known as the “ban on the profession.” More details about it and its implementation in modern Belarus can be found in the Centre for European Transformations’ report “The employment ban in Belarus – returning to the Soviet practices and unique features” (2023). The researchers note that the ban on the profession is a generalised phenomenon. Concerning the cultural sphere, it implies not only dismissals but also expulsions from universities and other professional educational institutions of creative orientation, withdrawal of licenses for publishers, accreditation for tour guides and guides-translators, “blocklists” of cultural figures, liquidation of public organisations and other ways to depriving professionals of the opportunity to carry out their professional activities legally in the country.

ADMINISTRATIVE OBSTACLES, CENSORSHIP AND A BAN ON THE DISSEMINATION OF BELARUSAN CULTURE

In 2023, the authorities continued to eliminate independent cultural activities while tightening control over the state-owned cultural sector in Belarus. The current conditions for the cultural sphere and the dissemination of Belarusian cultural products can be characterised by the following: total censorship of the book market and library funds, theatrical performances, concerts and exhibitions, film screenings, museum excursions and tourist routes, creative unions and public organisations; a ban on the titles and popularisation of works created by the cultural figures disloyal to the regime; raids of cultural venues and events by security forces; censorship of propagandists. The lists of “unreliable” cultural workers, “stop-lists” of performers, lists of “extremist” literature, forced liquidation of organisations, changes in the Code on Culture, registers of vetted specialists and “phone calls” from the Ministry of Culture, monitoring commissions and inspection visits, verbal warnings, “green light” for pro-Russian propagandists to attack Belarusian authors and their works constitute the formal and informal mechanisms of repressions and the nature of current state policy in the sphere of culture in Belarus.

A special mention should be made of the attacks by pro-government bloggers against national art. The opinion of propagandists influences the decision-making of state censors. Exhibitions permitted by the Ministry of Culture can suddenly be cancelled after being publicly criticised” by “experts” like Volha Bondarava [one of the pro-Russian activists]. The same applies to situations with other cultural events, books, objects of tangible heritage and other events that they have drawn attention to and complained about to the authorities.

In 2023, the monitors recorded 237 cases of censorship of cultural figures and organisations and 92 cases of administrative obstacles to the latter’s activities.

The repressions against the book publishing houses that published books by Belarusian authors and in the Belarusian language continued. On 10 January, Minsk’s Economic Court ruled to invalidate the certificate of state registration for self-employed entrepreneur Andrej Januškievič. The Januškievič publishing house was liquidated. The formal reason was the publication of Alhird Bacharevič’s novel The Dogs of Europe, a children’s book based on Joseph Brodsky’s poem Ballad about a Small Tugboat and Sviatlana Kozlava’s scientific monograph about the war Agrarian Policy of the Nationalists in Western Belarus: Planning. Transparency. Aggravation (1941-1944). In October 2022, the Ministry of Information labelled these three books “extremist materials.” In January, the forthcoming liquidation of the publishing house Knihazbor became known. The founder and publisher, Hienadź Viniarski, wrote about it on Facebook. In October 2023, the process was completed. On 11 April, the Minsk Economic Court ruled to terminate the certificate of state registration of self-employed entrepreneur Dzmitry Kolas. The oldest private publishing house, Zmicier Kolas, which has been operating in Belarus since the late 1980s, was liquidated. The reason is the publication of the collection of documents about the Polish-Belarusian borderline in 1939-1941, Liberated and Imprisoned, scientifically edited by Doctor of Historical Sciences Aliaksandr Smaliančuk. In January this year, the Ministry of Information added the collection to the list of “extremist materials.” Two other independent publishing houses – Goliaths and Limarius –were liquidated in 2022. We also note the liquidation of the Vita Publishing House. The information about it became known from the response of the Ministry of Information to the appeal of pro-Russian activist Volha Bondarava, who complained about the distribution of the book Where Did I Come From? published by this publishing house.

The monitors also recorded censorship of the school curriculum. Since the new academic year 2023/2024, Artur Volski’s fairy tale Native Words and Uladzimir Jahoŭdzik’s story Lark have been excluded from the list of works recommended for study in the framework of the subject “Literature” for the 4th grade of general secondary education institutions (another successful “case” of Volha Bondarava). Uladzimir Karatkievič’s historical novel Ears Under Your Sickle (replaced by The Black Castle of Alšany) and Aleś Razanaŭ’s poem Ragvalod Rules in the City (for additional reading) were removed from the curriculum of Belarusian literature for the 11th grade. The rejection of Karatkievič’s work was initiated by the pro-government propagandist historian Vadzim Gigin because of its alleged inconsistency with the “correct” historical memory. The novel mentions the rebel Kastuś Kalinoŭski, Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko, and the anti-Russian uprising in Poland in 1863-1864.

The state continues to interfere in what is on offer at bookshops. The products of liquidated publishing houses, writers disloyal to the regime, and historians, whose vision of specific periods of Belarusian history – in particular, the 1930s and the times of World War II – differs from the ideological line of the state, are withdrawn from the sales system. There is a tendency to purge the library collections. In 2023, it was not once heard that some city libraries, schools, and gymnasiums had removed the books by Svetlana Alexievich, the first Nobel laureate in the history of independent Belarus. The works labelled “extremist materials” disappear from the shelves and electronic catalogues.

The blockage of websites with materials on cultural topics happened again. In March 2023, it occurred to the Belarusian independent scientific, popular science, socio-political and literary-artistic magazine ARCHE arche.by (the blockage remains in place). In April, the website with audiobooks in Belarusian audiobooks.by was blocked. In July, it happened to the most extensive online library of Belarusian literature, kamunikat.org.

In late December 2023, the literature and art magazine Dziejasloŭ, in operation since September 2002, announced its closure. “With this issue, Dziejasloŭ is saying goodbye to you. Moving on, it will no longer be published as a magazine. It is a world trend that literary publications and printed publications, in general – some of them started hundreds of years ago, and some started dozens of years ago – now give way to electronic publications. But in our case, the main reason is different. We believe it is obvious and known to you,” the authors wrote in the last printed issue of the magazine.

***

In February, “the “stop-list” of performers banned in Belarus, containing 87 names of bands and artists, was published. Almost one in two (38 out of 87) of the listed performers/groups represents the Russian scene, every third (29 out of 87) is a Belarusian artist, and every fifth (18 out of 87) is a Ukrainian performer. During the year, we received confirmations from several sources about the prohibition of rotation on the radio, in clubs and other places of the performers whose names are on the “stop list”, so we consider this list reliable. The list of Belarusian performers included N.R.M., Dzmitry Vajciuškievič, Krambambulia, Palac, Navi Band, Hanna Šarkunova, Max Korž, Litesound and others.

In early January, a concert in Homiel dedicated to the 10th anniversary of the folk band Jahorava Hara was cancelled. Simultaneously, the musicians announced the forced suspension of their concert activities. Prime Hall, one of Minsk’s most famous concert venues, didn’t work for six months. In mid-January, the information about the temporary closure of the club “for technical reasons” appeared on the organisation’s website. According to the versions voiced in the media, Prime Hall had to suspend operations because of the performance by an artist from the “blacklist” at the New Year’s corporate party of the company that rented the venue. In June, Prime Hall resumed work.

In 2023, criminal prosecution for musical creation was recorded. The Tor Band members were charged with creating an “extremist formation” and sentenced to between 7.5 and 9 years in a medium-security penal colony for their songs.

***

The Ministry of Culture used a phone call to cancel the 9th edition of the independent offline festival of auteur film Non-Filtered Cinema, scheduled to take place at Minsk’s Mooon cinema in Dana Mall shopping centre on 24-26 March. Similarly, the festival’s educational film lectures were disrupted three times. In December, participants in the screening of “A Session of Unfilmed Cinema” were detained (also mentioned below in connection with the persecution of consumers of a cultural product). The Russian film What Men Talk About was removed from distribution by orders from the Ministry of Culture. The premier screening of the Belarusian psychological thriller Strange House, released in Russian distribution on 6 April, was cancelled and sent “for additional inspection.” At the request of the Ministry of Culture, the Russian-Belarusian series “For Half an Hour to Spring,” dedicated to the legendary Soviet times band Pesniary, was released in Belarus in a censored form. The faces of actors Dzmitry Jesianievič and Hieorhi Piatrenka were redacted. The primary exposition was significantly reduced during the transfer to another floor due to renovation works at the Museum of the History of Belarusian Cinema. Characteristically, it happened at the expense of “suspicious elements” both in the exposition itself and in the history of Belarusian cinema.

***

Ivan Kirčuk’s mono-performance at the Janka Kupala National Theatre did not occur. The National Theatre of Belarusian Dramaturgy stopped showing the play It’s All Her by Andrej Ivanoŭ. The productions, based on the plays by Julia Čarniaūskaja, directed by the former artistic director of the theatre, Aliaksandr Harcujeŭ, fired for political reasons at the end of December 2021, and other names, disappeared from playbills and posters. For reasons beyond the control of the organisers, the premiere of the interactive theatrical tour based on Uladzimir Karatkievič’s King Stakh’s Wild Hunt, scheduled for 4-6 November, was cancelled in the park “Grand Duchy of Sula.” The Ministry of Culture interfered and censored the exhibitions of Belarusian painting “Leanid Ščamialioŭ…Dedication” and “Exhibition of Belarusian Easel and Book Graphics of the XX-XXI Centuries” organised by the Union of Artists at the Palace of Arts. The opening of the exhibition “Forest” by the artist under the pseudonym Vova Televerdok did not take place. In December, the team of the cultural venue Vieršy, a space that hosted many concerts, film screenings, lectures and master classes, announced its forced closure.

***

Book presentations, lectures, and round tables were cancelled in Minsk and other cities of Belarus. Plays were removed from the repertoires, new productions were not allowed on stage, touring certificates were not given, and cultural figures “unreliable” for the regime were not allowed to participate in exhibitions, conferences, festivals, meetings and other events. “They were not selected”, “urgent repair of the premises”, “they are on the lists”, “we will not work with this moderator”, “they have not been checked”, “we cannot include your report” and other pretexts were used. Sometimes, authorities would respond with official replies to a request for an event permit, citing “violation of other requirements of legal acts” of Article 215, paragraph 1 of the Culture Code – without explanation. Due to the confidential nature of the information provided, we cannot voice a significant part of the censorship cases in this material.

Censorship and numerous cancellations of concerts, exhibitions, productions, film screenings and other similar events also affect the audience. All such events become inaccessible to people. The forceful persecution of consumers of cultural products is an extreme form of state interference in realising the right to participate in cultural life. On 13 January, about 80 people were detained and spent 5 hours in a bus – until all of them had their documents and phones checked. The group travelled with three guides to Siemiežava, Minsk region’s rural settlement, to attend the rile Kaliadnyja Cary (Christmas Kings), included in the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage. For the guides Ivan Sacukievič and Aleś Varykiš, the trip ended with 15 and 9 days of administrative arrest. On 10 June, the riot police from Brest stormed the territory of the estate “Stuly” and disrupted the performance of the folk puppet theatre Batlejka. All adult participants were ordered to go outside and lie on the ground face down in a “hands behind the head” position. Following their phone checks, six people were detained, including the manor’s owner, Larysa Byćko and musician Ihar Paliašenka. Several spectators received between 3 and 15 days in a detention centre. On 21 December, the organisers and spectators who came to the event of Unfiltered Cinema festival – A Session of Unfilmed Cinema – were detained. The detainees were sentenced to days of arrest. One should also mention the situation with the Redan youth subculture of Japanese animation fans. When teenagers attempted to gather in a shopping mall in Homiel (28 February) and Brest (1 March), they were detained en mass. The Investigative Committee described the incident as a crackdown on an attempted unauthorised mass event.

PRESSURE ON CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN THE CULTURAL SECTOR

Liquidation of non-profit organisations

According to Lawtrend monitoring, between the first liquidations in 2020 and late 2023, the non-profit sector in Belarus lost 958 organisations, including at least 228 that belonged to the cultural sector or had a cultural component in their activities. In 2023, 45 cultural organisations were forcibly liquidated. Among the most affected during this period was the historical and cultural heritage. On 10 January 2023, the Supreme Court ruled to liquidate the oldest public association, “The Belarusian Voluntary Society for the Protection of Monuments of History and Culture”, founded in Minsk in 1966 and headed by cultural historian Anton Astapovič since 2007. In April, Homiel regional court liquidated the historical and cultural public association “Heritage of Palessie.” The organisation’s enthusiasts were engaged in restoring the former building of the early 18th-century Catholic monastery in Mozyr and the 19th-century Gorvatt estate in Naroŭlia from the ruins. Also, in April, the Minsk Regional Court forcibly liquidated the local fund to restore the building of the architectural monument – the 16th-century former Bernardine monastery in Niaśviž. In May, the Minsk City Court liquidated the local “und “Cultural Heritage and Modernity”, chaired by Ala Staškievič, an expert of UNESCO and ICOM since its foundation in 2014. In June, the Hrodna Regional Court ruled to liquidate the local charitable foundation “Kreva Castle”, which was engaged in preserving this oldest 14th-century Belarusian architectural monument. In August, the Minsk Regional Court liquidated the local historical and cultural fund “LELIVA”, which was engaged in preserving the heritage of Čapskis’ family, including the improvement and reconstruction of the 17th-century manor complex in the village of Pryluki.

One should also note the facts of pressure and selective application of legislative norms by the state concerning organisations working with cultural heritage objects. For example, the executive authorities seized the property of Manors and Castles Ltd., which had bought and been restoring Platters’ manor in the Opsa settlement of Braslaŭ district, and the private unitary enterprise Majontak Padarosk, which was dealing with the manor complex in the same-name rural settlement in Vaŭkavysk district. The practice shows that the local vertical “takes care” of the owners of some objects and does nothing about others, which can remain neglected for years.

The forced liquidation also affected organisations that focused on preserving and developing national cultures and traditions. In April 2023, the Hrodna Regional Court ruled to forcibly liquidate the public association “Gimtine” in the village of Pielesa, the first Lithuanian organisation officially registered in Belarus back in 1993. In August 2022, the authorities closed down the Pielesa secondary school following an inspection from the Ministry of Emergencies, which allegedly revealed several fire safety violations. In November, the same court ordered the liquidation of another oldest Lithuanian organisation – Club Gervėčiai, registered in the village of Rymdzjuny in 1994. Thus, between 2021 and 2023, the history of at least four Lithuanian national CSOs was forced to end, and at least four more organisations decided to self-liquidate. Out of 11 non-profit organisations of Poles registered in Belarus, only two remained. Six were closed down forcibly, and three more self-dissolved. In 2023, the Belarusian-Iranian Friendship Society, the Ašmiany Roma Community, the Belarusian Association of Roma, the Centre of Ukrainian Culture “Sich”, the public association “Syrian Community”, and the International Public Organisation of Armenians “Urartu” were forcibly liquidated.

We also note the destruction by administrative coercion of public organisations preserving historical memory. Among them are the Belarusian Public Association of Victims of Political Repressions of the 1920-80s, the Hrodna historical-patriotic search club Arkona and the Homiel regional search public association Memory of the Fatherland. In February 2022, Ihar Svirydzienka, the head of the latter, publicly condemned Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine. It did not go unnoticed by the regime.

On 14 February 2023, Law No. 2″1-3 “On Amendments to the Laws on the Activities of Political Parties and Other Public Associations” was adopted. Under the revised law, public associations need to bring their statutes into compliance with the new requirements. It means additional leverage for the state in dealing with not-for-profits. Lawtrend experts predict that the completion of harmonizing statutes with the latest amendments will lead to more closed associations. As of today, according to Volha Smalianka’s estimates, about 25 per cent of registered NGOs have already disappeared.

Self-liquidation

At the end of 2023, Lawtrend listed 552 civil society organisations that decided to self-liquidate. We attribute at least 110 of those to the cultural sector. In 2020–2023, due to forced and self-liquidation (we do not include violations in the statistics), the non-profit sector of Belarus lost 1,510 public organisations, including at least 338 cultural or culture-related organisations.

Pressure on creative unions

In 2023, the pressure on creative unions (Union of Artists, Union of Designers and others) continued. On orders from the Ministry of Culture, a dossier was drawn up for each chairperson of a creative union to assess how well they meet the ideological requirements of the state. One of the consequences is the practice of membership suspension. To date, at least two dozen masters who, in one way or another, expressed their civic position have been unjustifiably expelled from the Union of Artists. Uladzimir Ceslier, Sviatlana Pietuškova and other artists, as well as political prisoners Aleś Puškin and Hienadź Drazdoŭ, who left Belarus, were among the first expulsions.

Moreover, it became known on 11 December that the Ministry of Culture demanded to destroy the art group “Pahonia,” created in 1990. In 2011-2016, the group was headed by artist Hienadź Drazdoŭ. On 4 May 2023, he was sentenced to three years in a penal colony. The details of his trial are unknown. The art group united about 50 people.

This is how the “normalised” logo of the Belarusian Union of Artists looks like (website http://belartunion.by/)

This is how the “normalised” logo of the Belarusian Union of Artists looks like (website http://belartunion.by/)

“EXTREMIST MATERIALS“

In 2023, the practice of adding texts, musical compositions, videos, and pages of cultural figures in social networks to the “List of Extremist Materials” was further developed. This is one of the ways the regime persecutes dissent under the guise of the fight against extremism. Before 2020, the list mainly contained neo-Nazi, nationalist or radical-religious materials. Since then, most materials have been included for political reasons. In 2023, the Ministry of Information added to the “extremist” list at least 182 books, magazines, music videos, websites, YouTube and Telegram channels, other materials on the topic of culture, history, Belarusian language, as well as the social media profiles of Belarusian cultural figures. The latter are partially mentioned in the section Designating the statements of cultural figures on social networks as “extremist.” We record all these cases for monitoring purposes with the wording “designated as extremist material.” It is important to note that the grounds on which the list is added to the list conflict with the standards of administration of justice and create harmful law enforcement practices. This list is not exhaustive: not all materials can be identified as cultural or related to cultural figures, and some pages have already been removed.

- Literature and history

In 2023, the Ministry of Information designated as “extremist” 26 fiction, historical or scientific books, the poems Winds Are Blowing and An Old Man is Talking by a 19th-century classic of Belarusian literature, Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič, and the preface by Jazep Januškievič in the book “Selected Works / Vincent Dunin-Marcin”ievič” – the hundredth volume of the Belarusian Book Collection project, published by Belaruskaja Navuka (Belarusian Science) in 2019. The full list of works of Belarusian classics, historians and other authors, labelled by the regime as “extremist materials”, can be seen on the website of PEN Belarus.

37 books (fiction, journalistic, scientific), poems and one book preface have been labelled “extremist” since 2021.

On 6 March, the list was supplemented with nine issues of the popular science journal Naša Historyja (Our History) and three issues of the independent scientific, popular science, socio-political and literary-artistic journal ARCHE, published in 2018–2020.

The following Telegram channels about the history of Belarus received the status of “extremist mat”rials”: on 27 February – Historyja channel (“Kanał pra našu historyju) on the list (It had already been on the list of “extremist formations” since June 2022); on 6 April – Belarus history (“History of Belarus in photos and short, interesting facts“); 13 April – local historian and guide Cimafiej Akudovič’s channel Belaruski Babylon (“Belarusian History in Extraordinary Angles”); 30 November – “Beer&History” (a historical club founded by Belarusians from Bialystok); 11 May – a closed Facebook group “My Minsk: Politics, History, Sociology“.

- Music

On 7 February, the punk anthem of the late” 1990s ”Our Home is Belarus” was declared “extremist.” On 8 February, the video and lyrics of the song “Extremist” (2023) by the band Dai Darohu! were declared “extremist”. This is the second video to become “extremist.” In August 2021, the video “Baju-baj” (2020) was first. On 17 August and 21 September, the group’s VKontakte and Instagram accounts were added to the list, respectively. 24 February became a black day for the “VKontakte” page of the Belarusian neofolk band Kryvakryž, whose opus magnum album “Malitvy Vainy” (2009) was deemed “extremely politicised, biased and Russophobic.” On 14 March, the list included the video “Sumarok –”Čerci” by the Sumarok band, containing footage of protests in Maladziečna in 2020. A year ago, an article about this video, published in the Rehijanalnaja Hazieta in October 2020, was labelled “extremist.” On 31 March, another video of the band “Sumarok – 2020” was deemed “extremist.” On 12 April, the musical compositions “2020”, “Tarakan”(demo) and “Papitsot” by the Children of Khrushchevka band, as well as its YouTube channel and social media pages, became “extremist”. On 26 April, another Ukrainian song “Ah, Bandero!” appeared on the list. In November”2022, “Our Father is Bandera, Ukraine is Mother” was declared “extremist”. On 25 May, four songs by the faceOFF “and – “Time!!”, “Guardians of the Galaxy”, “Hate” and “Spring” – were added to the list, as well as its VKontakte page. On 23 June, the YouTube channel Tyapin CREW, the website and social media pages of rapper Andrej Ciapin were added to the list.

- Film and other arts

On 24 February, the Salihorsk District Court of Minsk Region, among other things, declared the VKontakte group dedicated to the 2013 feature film Žyvie Bielaruś! || Viva Belarus! as “extremist material.” As the group’s description says, it is “The first fiction film about modern Belarus in the Belarusian language.” On 5 June, the same fate befell the YouTube channel Radio 97 ART, and on 27 July – the Instagram accounts karikatu.rama (illustrations) and belarus_culture_in_photography (Culture of Belarus in photos).

- Belarusian language and culture

On 6 March, the calender “Don’t Keep Silence in Belarusian 2021 in Pictures and Words” was declared “extremist”; 10 April – Telegram channel “Volnajamova” (“A local chat room for everyone who wants to speak Belarusian or is interested in the Belarusian language, literature, history“); On 22 May – Telegram channel “Only About the Language” (“A channel for those who think about the language. The channel is for those who think about and dabble in the language (“Both about the common language as a unique character and quality, and – first of all – about the Belarusian language with its baggage and problems”); on 5 July – Telegram channel, and on 9 October – Instagram “RazMova” (“RazMova’ – an interesting channel about the language”); on 19 December – Instagram “supermovaby” (“Encyclopaedia of good events, events and activities, intended to raise awareness and appreciation of Belarusians for themselves and our Belarusian language”).

The list of “extremist materials” includes the social media pages of the cultural and educational portal about Belarus Budzma Belarusami!; the site Association of Belarusians “Baćkaŭščyna” (“Association of Belarusian Diaspora from more than 20 countries of the world”); Telegram-channel Belarusian Youth Hub in Warsaw (“Assistance, support, implementation of cultural and educational projects”); Free Belarus Museum (“New cultural centre”); Telegram-channel Francišak Skaryna Library and Museum in London; Instagram Fundacja Talaka (“Traditional and contemporary culture, Belarusian language, music, art, theatre, film, or finally a meeting between people”); VKontakte account of Prastora KH (the organisation was forcibly liquidated in June 2021); the website and social media pages of Radio Wnet; Telegram-channel Belaruskaja Rada Kultury (in June 2022, it was designated as a “extremist formation”); social media pages of Spadčyna (“Club of Development and Future”) and others.

ATTACKS ON HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE – NATIONAL HISTORY OBJECTS AND POLISH MEMORIALS

The official policy of the current authorities is anti-national, anti-Western (particularly anti-Polish), and pro-Russian. This section will mention the facts of the fight against the history deemed “unnecessary” by the regime. We will give an example of destroyed objects of Belarusian national and Polish memorial heritage.

On the night of 30 March, in Zelva village, Hrodna region, the monument to the Belarusian dissident poetess Larysa Hienijuš, installed in 2003 on the premises of the Holy Life-Giving Trinity Church, was dismantled. It happened one week before the 40th anniversary of the writer’s death. The dismantling resulted from the actions of pro-government activist Volha Bondarava to denigrate the memory of Larysa Hienijuš. Since autumn 2022, the pro-Russian campaigner had been sending appeals to the ideologues at the Hrodna executive committees, the Office of the President, Minsk Diocese and other authorities, describing the poetess as “an unambiguously negative figure”, “an accomplice of Hitler’s occupiers” and “a Nazi criminal.” Despite the absurdity of the accusations and activist’s intermediate failures (in particular, the response from the Zelva District Executive Committee about the legality of the monument’s installation), the bust was eventually dismantled. In April, the memorial to the Belarusian academician, writer, public and political figure Vaclaŭ Lastoŭski, executed during the Stalinist terror, was vandalised in Kurapaty, the site of mass shootings and burials of the victims of repression. In May, wooden memorial crosses were damaged and desecrated with obscene inscriptions. In July, “through the efforts of the Communist Party,” as Bondarava wrote in her Telegram channel, a cross commemorating the Catholic priest, publicist and translator, one of the leaders of the Belarusian national liberation movement, Wincenty Godlewski, was removed from the premises of St Roch Cathedral in Minsk. “Hienijuš, Godlewski, who is next?” the evil propagandist asked triumphantly. A memorial sign honouring the 1863–1864 uprising rebels was dismantled at the Hrodna railway station. The authors of the Telegram channel Spadčyna noted that Belarusian laws treat it as a work of art theft. In October, new cases of vandalism against the victims of Stalin’s regime were recorded. The crosses commemorating Lastoŭski and repressed Poles were desecrated with insulting inscriptions. In May, such an incident took place in ‘Viciebsk Kurapaty,’ people’s memorial to the victims of Bolsheviks’ terror near the village of Chaisy: the crosses were broken, memorial plaques and signs to the pits where shootings took place in the 1937-40s were destroyed. It is known that the Viciebsk district police department refused to investigate the facts of vandalism.