This report has been prepared based on consolidated information collected by PEN Belarus’ monitoring group from open sources, through personal contacts, and via direct communication with cultural figures. The information reflects the situation as of the time of preparation and may be further updated as new data become available.

Despite measures to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information, certain gaps may remain, including in the identification or classification of individuals as cultural figures, due to limited public information. PEN Belarus welcomes clarifications and additional information you may be able to share. If you wish to report a violation (including confidentially) or clarify information contained in this material, please contact us at: [email protected], t.me/viadoma.

Given the situation in Belarus’s cultural sphere, the role of cultural figures in public life, and the importance of artistic expression for the preservation and development of cultural rights, we recognise Belarusian cultural figures as cultural rights defenders, in line with the approach formulated in the report of the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights (A/HRC/43/50, 2020) [1]. More information about the monitoring methodology is available here.

NB: For reasons of information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources that are subject to restrictions under the legislation of the Republic of Belarus.

Key monitoring findings: statistics and trends

Pardons and forced deportation of cultural figures from Belarus

Arbitrary detentions, administrative punishment and criminal prosecution

Conditions of detention and violation of cultural rights in places of imprisonment

Transnational repression of cultural figures

Censorship, book bans and other violations of cultural rights

Pressure on cultural organisations and communities

Culture-related materials designated as “extremist”

The Belarusian language, historical heritage and destruction of sites of memory

State policy in the cultural sphere

Conclusion

KEY MONITORING FINDINGS: STATISTICS AND TRENDS

The socio-political crisis triggered by the falsification of the 2020 presidential election and the subsequent violent crackdown on peaceful protests in Belarus remains unresolved. Five years on, in 2025, the crisis continues to manifest in systemic repression that profoundly affects the cultural sphere, constraining freedom of expression, narrowing the permissible themes, and curtailing the involvement of cultural figures in public life.

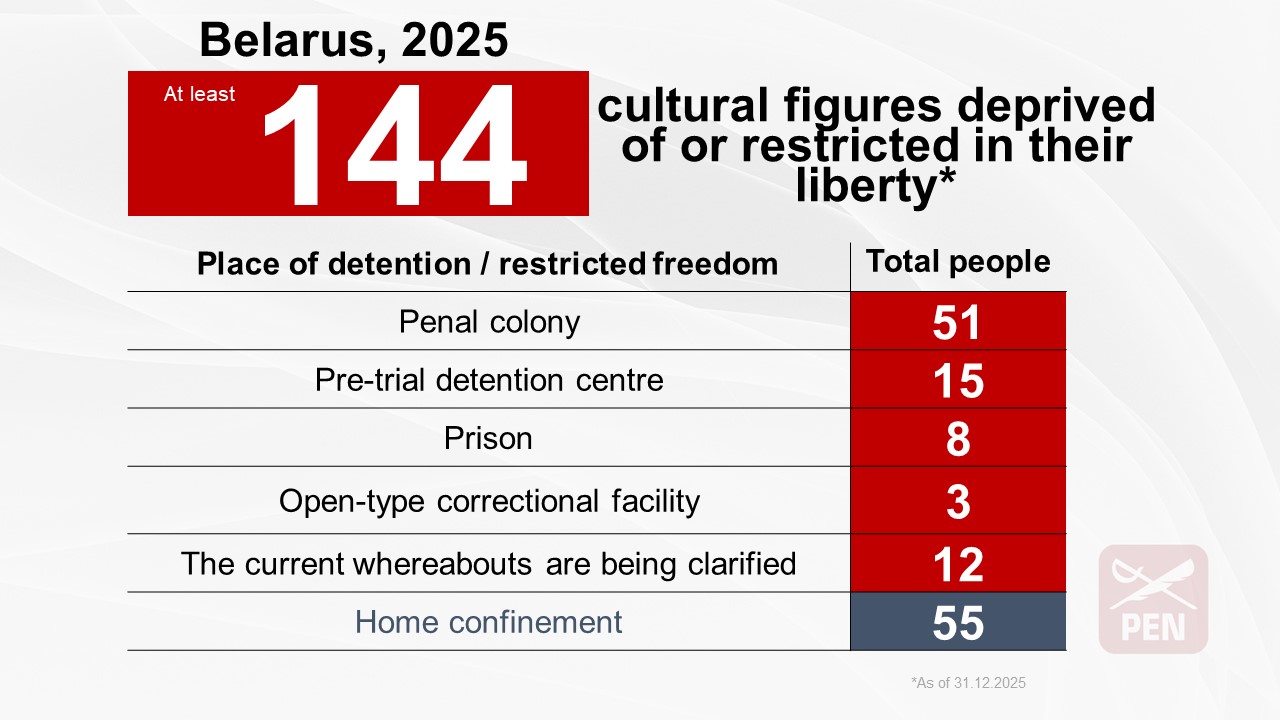

As of the end of 2025, at least [2] 144 cultural figures remained deprived or restricted of their liberty, including those under home confinement [3], among them 30 writers. Pressure within places of imprisonment persists, alongside arbitrary detentions and arrests, politically motivated criminal and administrative prosecutions, dismissals, intimidation, and smear campaigns. The most serious and systemic violation of the rights of cultural figures remains the denial of the right to a fair trial and effective access to justice.

Authorities have further developed the practice of early release combined with forced expulsion of political prisoners. 27 cultural figures were forcibly deported from Belarus. Transnational persecution has not abated and, in some cases, has escalated to threats to life and health.

The Ministry of Culture’s so-called “blacklist” now contains hundreds of names, and opportunities to present one’s creative work are critically restricted. Censorship in its broad sense – cultural, political, and ideological – remains the most widespread violation identified through monitoring.

Cultural initiatives both inside Belarus and abroad continue to be designated by the state as “extremist formations”, while individuals are prosecuted for allegedly facilitating extremist activity. The number of cultural projects, works, and social media accounts belonging to cultural figures that have been declared “extremist materials” continues to grow. In 2025 alone, the list of printed publications allegedly capable of harming the national interests of the Republic of Belarus was expanded six times with new titles.

The Belarusian language, the tongue of the titular nation, continues to face discrimination and remains in a vulnerable position. New cases of improper treatment of objects of historical and cultural heritage and sites of memory have been documented.

In January 2025, state cultural policy was largely oriented towards public support for Alaksandr Łukašenka, who had been in power for three decades, ahead of the presidential election held on 26 January. Other key directions of state policy include tighter control over the cultural sphere, its further ideologisation, the monopolisation by the state of the right to define and interpret historical memory, the strengthening of cooperation with Russian cultural institutions and the replacement of local professionals with specialists from Russia, the promotion of artists loyal to the authorities, and several other related trends.

- The monitors recorded 1,435 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures in 2025.

- The most frequent types of violations identified in the overall monitoring were the designation of culture-related materials or cultural figures’ social media accounts as “extremist” (356 cases), censorship (333 cases), and violations of the right to a fair trial and access to justice (142 cases).

- Regarding individual cultural figures, the most frequently documented violations were breaches of the right to a fair trial (130 cases) and criminal prosecutions (95 cases). Cultural organisations and communities, by contrast, were most affected by censorship (55 cases) and administrative obstruction to their activities (44 cases), including forced liquidation.

- As of 31 December 2025, Belarus held 1,131 political prisoners [4], among them at least 77 cultural figures.

- At least 144 cultural figures are deprived or restricted of their liberty, including those held in prisons, penal colonies, pre-trial detention centres, open-type correctional institutions, or in home confinement. Of these, 51 persons are held in penal colonies, 15 in pre-trial detention centres, 8 in prisons, 3 in open-type correctional institutions, and 55 in home confinement. The current whereabouts of a further 12 individuals remain unknown to human rights defenders.

- Criminal cases were initiated against 95 cultural figures. Nearly every second case involves the prosecution of political emigres.

- At least 66 cultural figures were subjected to criminal liability, including three persons tried in absentia. In addition, no fewer than four former political prisoners who managed to leave Belarus were later prosecuted during in-absentia trials for allegedly “evading the serving of their sentences”.

- At least 62 individuals from the cultural sector were subjected to arbitrary detention, with three people detained twice.

- Administrative persecution was recorded against 24 cultural figures, based on 26 offence reports.

- 27 cultural figures from among those pardoned in 2025 were forced into exile from Belarus.

- 60 individuals were added to the List of Citizens of the Republic of Belarus, Foreign Nationals or Stateless Persons Involved in Extremist Activity, while 10 individuals were included in the List of Organisations and Individuals Involved in Terrorist Activity. At least 61 cultural figures are listed as alleged participants in so-called “extremist formations”.

- 13 cultural civil society organisations were subjected to forced liquidation.

- 222 books – fiction, non-fiction, and historical works – were added either to the List of Extremist Materials or to the list of printed publications whose distribution is deemed “capable of harming the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”.

- 97 cases of improper treatment of historical and cultural heritage sites and sites of memory were documented.

TRENDS AND FORMS OF PERSECUTION:

- Restricted access to information. Since 5 March 2025, public access to the electronic schedule of court hearings on the Supreme Court’s website has been closed. This website was one of the key sources of information on judicial proceedings. Its removal has significantly hindered human rights monitoring of administrative and criminal cases against dissenters, including cultural figures. The section on in-absentia trials titled “Special Proceedings” was also removed from the website.

- Delayed visibility of repression. Information about detentions, arrests, and court rulings is increasingly becoming known to human rights organisations with significant delay (several months).

- Shifts in the structure of violations. Compared to 2024, 2025 saw a marked increase in censorship cases and the designation of materials as “extremist”. For the first time, violations related to the protection of historical and cultural heritage entered the Top 10, alongside the practice of designating cultural figures as participants in “extremist formations”. At the same time, a decline in the number of cases recorded in real time – such as arbitrary detentions, administrative persecution and criminal prosecution of cultural figures – largely reflects restricted access to official and public information and a reduction in available documentation channels.

- Mass criminal cases. One of the largest criminal cases in 2025 was the so-called Belarusian Hajun case, which centred on the alleged dissemination of socially significant information regarding the movement of Russian troops and military equipment across Belarus. Among those targeted were cultural figures.

- Inadequate conditions of detention. Conditions of incarceration for cultural figures continue to fall short of basic international standards and national legislation and, in some cases, may amount to inhuman treatment. State pressure often continues even after individuals have served their full sentences.

- Control at border crossings. Searches and so-called “interviews” with cultural figures at border crossings persist, alongside arbitrary detentions and arrests of individuals returning from abroad.

- Extra-judicial forms of persecution. These include summonses for “preventive conversations” with law enforcement bodies or workplace “security officers”; coercion into signing pledges not to engage in “extremist activity”; checks of mobile devices and social media accounts; the creation of fake profiles in the names of cultural figures; dismissals or pressure aimed at forcing resignation; as well as persecution of political émigrés and their relatives remaining in Belarus.

- Trials in absentia. The practice of in-absentia trials continues, including proceedings to change the regime of punishment for alleged “evasion” of sentence enforcement.

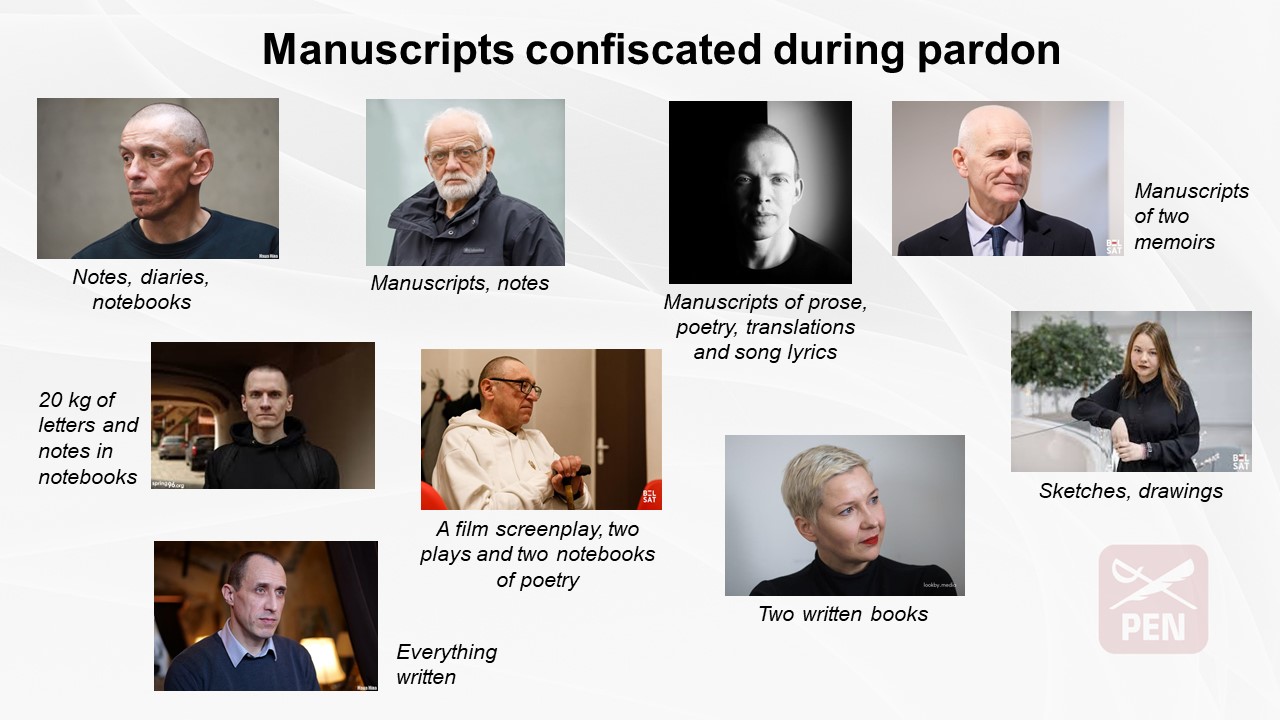

- “Pardons” accompanied by rights violations. Several waves of pardons of political prisoners took place in 2025, some of which were accompanied by forced deportation from Belarus and carried out in violation of basic procedural safeguards. During releases, a significant body of texts and manuscripts created by cultural figures while in prison was confiscated.

- Violations of property rights. Repression has extensively affected the property sphere, including the confiscation of real estate and other assets of convicted individuals, followed by their sale at auction. In October 2025, for example, Viktar Babaryka’s art collection was put up for auction.

- Dismantling of non-state cultural infrastructure. Kvitki.by, the largest ticketing operator in Belarus, stopped selling tickets and was placed into liquidation.

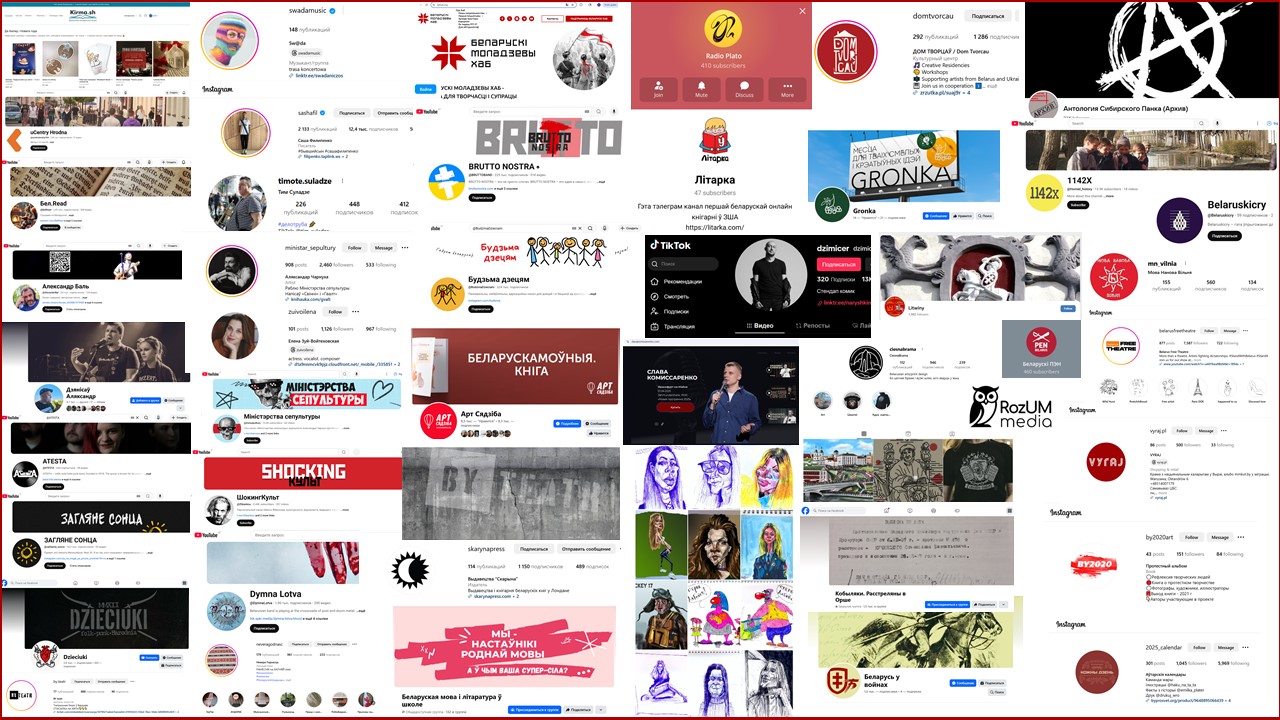

- Designation of cultural initiatives as “extremist”. In 2025, this practice affected not only projects operating in exile – such as Gronka, Žyccio-Malina, and the music band Dzieciuki – but also initiatives operating within Belarus, including Skład Butelek, Radio Plato, Borysthenis, and Da Zoraŭ.

- Expansion of the practice of designating “extremist materials”. Books and social media accounts of cultural figures were declared “extremist”, including those belonging to individuals in prison or shortly before their release (such as Zmicier Daškievič, Uładzimir Mackievič and Mikoła Dziadok), as well as individual names and nicknames, including kasiavadanosava and dzimicer (associated with Kaciaryna Vadanosava and Dzmitry Naryškin).

- Exclusion from public activity. The practice of barring “unreliable” artists from public performances continues, justified by alleged threats to “national security and public order”.

- Bans on literature. The list of books prohibited from distribution on the grounds of alleged threats to the “national interests” of the Republic of Belarus has expanded significantly.

- “Normalisation” of creative unions. Pressure on creative unions continues, including the use of coercive measures such as preventive detentions ahead of congresses and electoral procedures of the Belarusian Union of Artists.

- Distortion of historical memory. A persistent trend is observed towards the displacement and distortion of historical memory through the dismantling or disappearance of memorial signs, the closure of exhibitions, and the replacement of specific historical narratives with uniform state ideological rhetoric.

- Vulnerability of the Belarusian language. The status of the Belarusian language remains problematic, characterised not only by insufficient institutional support but also by practices of restriction, marginalisation and persecution of its use in key areas of public and cultural life.

- Ideological control of cultural institutions. State cultural institutions remain subject to strict ideological oversight, including informal bans on cooperation with non-state organisations and a structured system of support and incentives for regime-loyal actors.

- Slowdown in the liquidation of NGOs. The slowdown in the campaign of forced liquidation of non-governmental organisations, including cultural bodies, first observed in the first quarter of 2025, persisted through to the end of the year. This appears to have been largely because the pool of organisations still vulnerable to such measures had been effectively exhausted.

PARDONS AND FORCED DEPORTATION OF CULTURAL FIGURES FROM BELARUS

In 2025, several waves of pardons for political prisoners took place in Belarus, including cultural figures. On 22 January, Belarusian language and literature teacher Alena Stachiejka was released. On 8 May, photographer Alaksandr Ziankoŭ was freed. The former chair of the Jewish community, Raman Smirnoŭ, was released on 2 July.

The pardons covered at least 30 cultural figures. In addition to the three individuals mentioned above, a further 27 representatives of the cultural sector — including 14 writers — were released following mediation by the United States government, following visits to Minsk by John Coale, Donald Trump’s Special Envoy for Belarus. All were freed on condition of subsequent forced deportation from the country.

On 12 February, poet, translator, and journalist Andrej Kuzniečyk was pardoned and transferred to Lithuania, along with two other political prisoners.

On 21 June, philologist and Italianist Natalla Dulina, journalist and cultural writer Ihar Karniej, and cultural manager and blogger Siarhiej Cichanoŭski were released, along with 13 other political prisoners.

On 11 September, released were philosopher Uładzimir Mackievič; journalist, cultural manager and publisher Pavieł Mažejka; publicist Zmicier Daškievič; prison prose writer and blogger Mikoła Dziadok; non-fiction internet author and blogger Pavieł Vinahradaŭ; documentary filmmaker Łarysa Ščyrakova; local historian and journalist Jaŭhien Mierkis; founder and editor-in-chief of Rehijanalnaja hazieta Alaksandr Mancevič; architect and musician Alaksiej Silenka; cameraman and cover performer Hleb Hładkoŭski; and activist and author of musical works Siarhiej Sparyš. Altogether, 52 people were released that day, 40 of whom were recognised as political prisoners.

On 13 December, 123 individuals were released and deported to Lithuania and Ukraine. Among them were literary scholar and human rights defender, Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aleś Bialacki; lawyer, writer and bard Maksim Znak; philanthropist, businessman and politiсian Viktar Babaryka; musician, cultural project manager and public figure Maryja Kalesnikava; writer and civic activist Pavieł Sieviaryniec; publicist and activist Alena Hnaŭk; writer, translator and journalist Alaksandr Fiaduta; translator Siarhiej Paŭłavicki; DJ Arciom Makaviej; musician and screenwriter Kirył Vieviel; Japanese language lecturer and Japanese citizen Nakanishi Masatoshi; and Baranavičy State University linguistics student Hanna Kurys.

Among those released were several individuals whose prison terms were close to completion. Natalla Dulina, for example, told independent media that she had only a few months left in her sentence, after which she would be able to decide for herself whether to remain in her country or leave.

During deportation, political prisoners were not informed of what was happening until the moment they crossed the border into Lithuania or Ukraine and were handed over to diplomatic representatives. In several cases, transportation involved degrading treatment, including the use of hoods, blindfolds and handcuffs. Some individuals were transferred to Ukraine, a state currently engaged in armed conflict.

Forced deportations were carried out without the issuance of official documentation confirming release. Some individuals were not even in possession of their primary identity document – their passport – which subsequently creates serious obstacles to legalisation outside the Republic of Belarus.

Forced displacement, uncertain legal status, confiscation of passports and other violations affected a range of rights of former political prisoners, including freedom of movement, freedom to choose one’s place of residence, the right to nationality, and a wide spectrum of fundamental human rights related to family life, property, employment, healthcare and social protection. In response to the intensification of forced expulsions of pardoned political prisoners, a coalition of Belarusian human rights organisations issued a joint statement [5].

It must be emphasised that, despite the series of releases in 2025, there are no grounds to speak of a reduction in repression in Belarus – either generally or within the cultural sphere. During the same period in which 30 cultural figures were pardoned, at least 34 cultural workers were newly recognised as political prisoners, and at the end of 2025, there were a total of no less than 1,131 political prisoners in Belarus.

The releases were welcomed, though with caution, by the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Belarus, Nils Muižnieks. He noted that “the Belarusian authorities show no signs of changing their policies or practices of repression and have made no statements in this regard”, providing no grounds to speak of any normalisation of the situation in the country [6].

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS, ADMINISTRATIVE PUNISHMENT AND CRIMINAL PROSECUTION

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS

In 2025, at least 62 cultural figures were subjected to arbitrary detention or arrest, three of them more than once. In approximately two-thirds of documented cases, detention led to the opening of criminal proceedings.

Those detained included non-fiction writer Cina Pałynskaja; musician, radio host and composer, and leader of the folk-modern band Palac, Aleh Chamienka; artist Aksana Šalapina; head of the medieval re-enactment club Borysthenis, Pavieł Pastuchoŭ (Stankievič); street artist Aleh Łaryčaŭ; director of the liquidated Ukrainian Cultural Centre Sich, Valancina Łohvin; gusli player and vocalist of the medieval music group Stary Olsa, Aleś Čumakoŭ; and dozens of other representatives of the cultural sphere.

In parallel, 2025 also saw detentions among cultural workers previously regarded as loyal to the authorities, primarily in the concert and events sector. According to the independent outlet Naša Niva, the trigger was the discovery on one detainee’s phone of a Telegram chat called “Org BY”, created in early 2020 to exchange experience in organising events during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was followed by the detention of managers and representatives of major event companies, including Illa Pijatroŭski, director of Blackout Studio; Alaksandr Manyšaŭ, associated with the agencies Atom Entertainment and Unbreakable; and members of the management of the country’s largest ticket operator, Kvitki.by. The chat itself was designated an “extremist formation”. In the related cases, corruption, economic and anti-monopoly charges were also invoked; some detainees were released after “cooperating” with the investigation.

ADMINISTRATIVE PUNISHMENT

Administrative proceedings were recorded against 24 cultural figures in 2025, based on at least 26 administrative offence reports. In several instances, administrative measures preceded the opening of criminal cases.

Since 2022, the most frequently used ground for administrative persecution has remained Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Distribution of extremist materials”), the application of which is directly linked to the rapid expansion of the “National List of Extremist Materials”. Article 24.23 (“Violation of the procedure to organise or hold mass events”) also continues to be widely applied, now primarily in the form of so-called “picketing on social media”.

A key highlight of 2025 was the official documentation of an administrative prosecution, initiated under Article 10.9 of the Code of Administrative Offences for “Violation of electoral legislation”. On 26 January 2025, Belarus held its presidential elections, and the Central Election Commission noted several instances of ballot papers being photographed on election day. We are aware of at least one administrative charge under this provision against a cultural figure, though more such cases may exist.

Each year, establishing the precise grounds and circumstances of administrative prosecution becomes more difficult. In 40 % of the cases recorded in the reporting period, the specific articles under which offence reports were filed remain unknown, and the outcome of every second court decision could not be established. Available data, however, indicate that the most common sanction remained 15 days of administrative arrest – imposed in at least one-third of cases.

Administrative arrest or state-imposed fines affected cultural figures from a wide range of fields, including librarians, poets, history teachers, actors, guitarists, cultural scholars, conductors, photographers, musicians and historical re-enactors.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION

In 2025, criminal proceedings were recorded against 95 cultural figures, 55 of whom were in Belarus and 40 abroad. Transnational repression is examined in a separate section; the focus here is on the situation within the country.

Of the 55 cultural figures subjected to politically motivated criminal prosecution within Belarus in 2025, 47 faced such charges for the first time. Six were already serving prison sentences and recognised as political prisoners when new charges were brought against them. Two others – Wikipedia contributor Ivan Marozaŭ and journalist and local historian Alaksandr Lubiančuk – were detained again after fully serving their previous sentences.

The reasons for bringing criminal charges have not changed and consistently involve expressing views and alleged political disloyalty. These reasons cover participation in the 2020 protests, openly criticising authorities, involvement in pro-democracy or other civic activities, and ongoing prosecutions in prisons, such as the deliberate extension of sentences under Article 411 of the Criminal Code (“Malicious disobedience to the administration”). It appears that the approaching deadline for the statute of limitations on participation in the 2020 protests (Article 342 of the Criminal Code), set for the end of 2025, has spurred a rapid increase in its use to prosecute as many individuals as possible before its expiration.

Among the most extensive collective criminal proceedings in 2025 was the “Belarusian Hajun” case, which involved individuals from the cultural sphere. This segment also examines the detentions of editors responsible for the Belarusian-language version of Wikipedia.

The “Belarusian Hajun” case

In January 2022, shortly before the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, civic activist and cultural manager Anton Matolka launched the OSINT monitoring project Belarusian Hajun [7], aimed at tracking the movement of Russian military equipment and troops across Belarusian territory. In February, the initiative launched a Telegram channel to publish collected information. As early as March 2022, the Ministry of Internal Affairs designated the channel an “extremist formation”.

Three years later, in February 2025, the initiative reported unauthorised access by security services to its chatbot data and the risk of identifying users who had submitted information. Shortly thereafter, the project ceased operations. Mass detentions of individuals suspected of submitting information to the chatbot occurred, followed by criminal prosecution under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code (“Facilitating extremist activity”).

As of the end of 2025, nearly 200 individuals are known to have been implicated in the “Hajun case”, including at least 11 cultural figures – among them historians, local historians, musicians and photographers. Eight of them were reportedly sentenced in 2025 to various penalties ranging from restriction of liberty in an open-type facility or home confinement to imprisonment in a correctional colony.

The prosecution of individuals who provided information via the project’s chatbot is repressive. It criminalises actions that constitute the exercise of the right to seek and impart socially significant information. The criminal cases brought against those involved, including cultural figures, represent yet another example of the systemic restriction of freedom of expression and the right to information, and of the use of “extremism” legislation as a tool of political repression.

Arrests of Belarusian Wikipedia administrators

The repressive policies of 2025 also included the arrest of those managing the Belarusian Wikipedia section.

After 13 March, the community lost contact with Kazimier Lachnovič, one of the four administrators of the section using Taraškievica orthography. For more than six months, neither his detention nor even his identity was confirmed. Only in November did the Prosecutor General’s Office announce [8] that a university lecturer had been sentenced to two years’ imprisonment and a fine for “discrediting the Republic of Belarus”. According to the charges, between 2020 and 2025, he posted 25 text entries on Wikipedia, allegedly containing “knowingly false information” about history, state symbols, presidential elections, referendums, and the activities of state bodies and paramilitary organisations. Journalists from Naša Niva later identified him as Illa Baryskievič, who had long maintained anonymity while publishing critical materials on political topics.

On 17 April, another administrator, Volha Sitnik (username “Homelka”), also ceased communication. She was detained that same day and soon released, but re-detained on 7 May. In June, one of her accounts was reportedly used to disseminate false information in Belarusian diaspora chat groups. Sitnik spent around six months in detention before being sentenced under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code (“Facilitating extremist activity”) to home confinement.

On 15 May, the editor and longest-serving administrator of Belarusian Wikipedia, Maksim Lepušenka, was detained. He was later sentenced to two and a half years in home confinement under Article 342 of the Criminal Code for participation in the 2020 protests.

The detention of several administrators of the Belarusian-language Wikipedia within a short period bears the hallmarks of coordinated pressure, a conclusion reinforced by publications in state propaganda media. Shortly after the disappearance of the first administrator, the state outlet Belarus. Today published an article [9] portraying Wikipedia as a “weapon of information warfare” and the Belarusian-language section as a project allegedly edited from Poland.

CRIMINAL CONVICTIONS

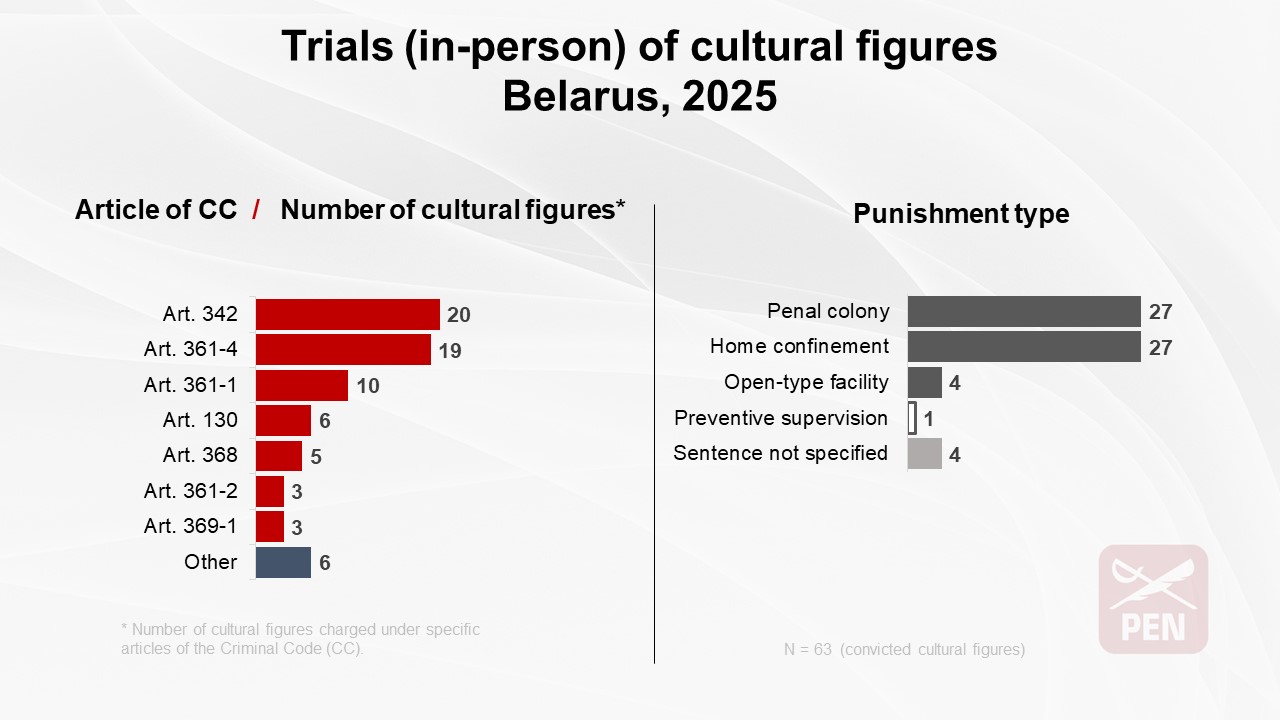

In 2025, verdicts were handed down against at least 66 cultural figures, including three sentences delivered in absentia under special proceedings. For six of those convicted, this was not their first politically motivated sentence.

The three most frequently applied provisions [10] in in-person criminal prosecutions were:

- Article 342 of the Criminal Code (“Organising, preparing or actively participating in actions that grossly violate public order”) – 20 individuals.

- Article 361-4 (“Facilitating extremist activity”) – 19 individuals.

- Article 361-1 (“Creation of or participation in an extremist formation”) – 10 individuals.

At least 27 cultural figures received prison terms in minimum- and medium-security penal colonies. 27 were sentenced to home confinement. Four were sentenced to restricted freedom in open-type correctional facilities. In four cases, human rights defenders have not yet received information about the court’s ruling; these cases are likely to have involved either imprisonment or restricted freedom in an open-type facility. In one case, preventive supervision was imposed.

The sentence of Nina Bahinskaja

The legal pursuit of Nina Bahinskaja, a 78-year-old civic activist who personifies peaceful resistance in Belarus, represented one of the most noteworthy criminal cases of early 2025. Over the decades, she has publicly defended the right to display national symbols, resulting in repeated state-sanctioned persecutions, including detentions, financial penalties, property confiscation, and reductions in her retirement income.

In early May, information emerged that criminal proceedings had been initiated against Bahinskaja under Article 342-2 of the Criminal Code [11] (“Repeated violation of the procedure for organising or holding mass events”), based on administrative penalties imposed in 2024 under Article 24.23 of the Code of Administrative Offences for using national symbols. Case materials also included a white-red-white flag and a poster bearing the historic Pahonia (Pursuit) coat of arms, seized during a search.

During the investigation, Bahinskaja was repeatedly referred for psychiatric examination. On 30 May, the court found her guilty in a closed hearing but applied Article 79 of the Criminal Code (“Conviction without sentencing”), limiting the penalty to preventive supervision.

The following cultural figures were convicted in 2025:

– Librarian Julija Łaptanovič (Art. 361-4 CC, 2.5 years in a penal colony) [12];

– Choir member Daniel-Landsey Keita (Art. 342 CC, 2 years in a penal colony);

– Artisan and owner of the jewellery workshop Samarodak, Michaił Łabań (Art. 361-2 CC, 2.5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type facility) [13];

– Cultural manager and businessman Eduard Babaryka (Art. 411 CC, sentence unspecified);

– Musician and screenwriter Kirył Vieviel (Arts. 361-1 and 130 CC, additional 1.5 years in a penal colony);

– Writer and anarchist Alaksandr Franckievič (Art. 411 CC, sentence unspecified);

– Belarusian language and literature teacher Anžalika Alasiuk (Art. 368 CC, sentence unspecified);

– Actress, model and flight attendant Vieranika Žałuboŭskaja (Art. 342 CC, 1 year in a penal colony);

– Writer and journalist Palina Pitkievič (Art. 361-1 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Historian and teacher Viktar Kucharčuk (Art. 130 CC, home confinement);

– Japanese language lecturer Nakanishi Masatoshi (Art. 358-1 CC, 7 years in a penal colony);

– Writer and journalist Alena Pankratava (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Owner of the ethnographic shop Cudoŭnia, Andrej Niesciarovič (Art. 342 CC, 1.5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility);

– Civic activist Nina Bahinskaja (Art. 342-2 CC, preventive supervision);

– Cultural activist Jaŭhien Bojka (Arts. 361-1 and 361-3 CC, 5 years in a penal colony);

– Former director of publishing houses Vadzim Pažyviłka (Art. 361-2 CC, home confinement);

– English teacher Alena Brazinskaja (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– IT specialist and dance competition prize-winner Siarhiej Sałažencaŭ (Art. 361-2 CC, penal colony);

– Founder of Devil Dance Studio Alaksandra Ašurka (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Head of the historical club Mindoŭh, Aleh Zielanko (Art. 361-4 CC, sentence unspecified);

– Local historian and religious studies scholar Pavieł Łaŭrynovič (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Student of Minsk State Linguistic University Alina Šaŭcova (Art. 361-1 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Belarusian Wikipedia administrator Maksim Lepušenka (Art. 342 CC, 2.5 years of home confinement);

– Journalist and local historian Aleh Supruniuk (Art. 361-1 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Actress and model Kaciaryna Javid (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Writer and journalist Rusłan Raviaka (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Librarian Iryna Kiškurna (Art. 361-1 CC, 2 years in a penal colony);

– Non-fiction author Ivan Marozaŭ (Art. 368 CC, 2.5 years in a penal colony);

– Artist Ihar Rymašeŭski (Art. 130 CC, 1 year and 2 months in a penal colony);

– Artist Ludmiła Ščamialova (Art. 130 CC, 1 year and 2 months in a penal colony);

– Jazz singer Vieranika Janoŭskaja (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Vocal teacher Maryna Rapaviec (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Amateur drummer Volha Mikałajeva (Arts. 361-1 and 342 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Librarian Anastasija Trubčyk-Dzivakova (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Musician Michaił Stocik (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Accordion teacher Lilija Pažaryckaja (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Accordion teacher Alaksandr Pažarycki (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– Local historian Jaŭhien Staravojtaŭ (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Journalist and writer Ihar Iljaš (Arts. 361-4 and 369-1 CC, 4 years in a penal colony);

– Poet and bard Valeryj Pazniakievič (Art. 368 CC, 3 years of restricted freedom);

– Musician and cultural manager Anatol Volski (Art. 361-4 CC, sentence unspecified);

– Historian and tour guide Anton Arciuch (Art. 361-4 CC, 3 years of restricted freedom);

– Artist Pavieł Ksiandzoŭ (Art. 361-1 CC, 2.5 years in a penal colony);

– Belarusian Wikipedia editor Volha Sitnik (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Designer Dzmitry Caruk (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Artist Aksana Šalapina (Art. 361-4 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Photographer Vadzim Zdaraviennaŭ (Art. 368 CC, 2 years in a penal colony);

– Founder of the art village Čyrvony Kastryčnik, Kirył Kraŭcoŭ (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Historian and ethnographer Alaksiej Drupaŭ (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Actress Alena Barsukova (Art. 342 CC, home confinement);

– German language teacher Jarasłava Chromčankava (Arts. 361-4 and 369-1 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Belarusian Wikipedia editor Illa Baryskievič (Art. 369-1 CC, 2 years in a penal colony);

– Musician and dancer Tacciana Łukjanava (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– English teacher Alaksandra Dubroŭskaja (Art. 361-1 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– Senior lecturer Alena Safronava (Art. 361-1 CC, sentence unspecified);

– Choreographer Vojciech Hrabicki (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Former head of the Ukrainian Cultural Centre “Sich”, Valancina Łohvin (Arts. 368, 130 and 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– IT promoter of the Belarusian language Viktar Haŭryłaviec (Art. 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Archivist Uładzimir Monzul (Arts. 130 and 361-4 CC, home confinement);

– Musician and event organiser Ivan Falitar (Art. 361-4 CC, 3 years in a penal colony);

– as well as at least three other cultural figures.

Under special proceedings, at least three cultural figures in exile were sentenced in absentia.

CONDITIONS OF DETENTION AND VIOLATIONS OF CULTURAL RIGHTS IN PLACES OF IMPRISONMENT

CONDITIONS OF DETENTION IN PLACES OF IMPRISONMENT

In 2025, 76 violations of detention conditions in closed institutions were documented involving 36 cultural figures. The most common practices included arbitrary placement in punishment cells and cell-type premises; fabricated disciplinary charges; psychological pressure; isolation and prolonged incommunicado detention; inadequate medical care; forced labour in harsh conditions; censorship and severe restrictions – or complete bans – on correspondence; deprivation of parcels and visits; and constant, penetrating cold. Within the Belarusian penitentiary system, a political prisoner is effectively presumed to be a “violator”, and the label of “extremist” is persistently emphasised. Daily life unfolds under a state of permanent anxiety.

Writer, human rights defender and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aleś Bialacki, released by pardon at the end of 2025, spent more than seven years in Belarusian prisons, including four years and four months during his second imprisonment. In interviews, he noted that both fifteen years ago and today, the penitentiary system is designed to restrict the individual and erode human dignity – particularly in the case of political prisoners.

Publicist and anarchist Mikoła Dziadok, also twice a political prisoner, speaks of a sharp intensification of pressure within the system after 2020. During nearly five years of his second imprisonment, he reports experiencing physical beatings, cold torture, gas sprayed into his eyes, insults and humiliation, provocations by cellmates, attempts to force him into a “low social status” [14], deprivation of parcels, letters and phone calls, and almost a year spent in punishment cells. Publicist and activist Alena Hnaŭk spent nearly half of her four-year sentence in punitive confinement and cell-type premises.

In 2025, musician and IT specialist Vadzim Hulevič remained in a cell-like room. Journalist and publicist Andrzej Poczobut, after another term in a punitive confinement, had his cell-type regime extended for a further six months; throughout his imprisonment, he has not had a single visit from his family. After completing a three-year prison regime, prison prose author and anarchist Ihar Alinievič and history promoter Eduard Palčys were transferred to penal colonies, where they were again placed in punitive confinement and cell-type premises. Poet, blogger and journalist Dzianis Ivašyn is regularly sent to punishment cells and has been deprived of telephone calls with his family for over a year.

The practice of deliberately extending prison terms continues. In 2025, cultural manager and businessman Eduard Babaryka and prison prose author and anarchist Alaksandr Franckievič faced repeat trials under Article 411 of the Criminal Code (“malicious disobedience to the administration”). Franckievič was additionally assigned a three-year prison regime and has been held incommunicado for over a year; his mother also remains in politically motivated detention.

Prolonged isolation was applied to other prominent figures. Maksim Znak spent more than five years in prison, nearly three of them without contact with family or lawyers. A similar regime was imposed on Viktar Babaryka and Maryja Kalesnikava before their pardon.

Systemic restrictions on correspondence have also been documented. According to available information, Andrzej Poczobut has been denied contact with his family. Journalist and writer Ihar Iljaš has been unable to correspond with his wife, the political prisoner Kaciaryna Bachvałava (Andrejeva), despite the absence of any formal prohibition on correspondence between prisoners. In the entire year of 2025, Aleś Bialacki received one letter from his wife, and not a single one was sent from him from the colony. Local historian and activist Uładzimir Hundar was allowed to receive his first food parcel in two years.

Throughout 2025, alarming reports continued regarding the health of political prisoners and inadequate medical care. Information emerged about vision loss suffered by cultural expert Vacłaŭ Areška; deteriorating eyesight in Uładzimir Hundar; fainting spells experienced by political analyst and publicist Valeryja Kasciuhova; denial of access to essential medication and chronic illnesses affecting writer and journalist Siarhiej Sacuk.

Forced labour under harsh conditions for token pay remains a serious concern. Documentary filmmaker Łarysa Ščyrakova worked full-time in a sewing workshop in a women’s colony, receiving only a negligible wage. Poet Andrej Kuzniečyk, released in February 2025, recalled his work in the colony during an interview for the Mediazona. Belarus:

“The work kept changing, but it was almost always outdoors, under the open sky. I carried sawdust to the boiler room, loaded pallets, cut production waste for burning, and cleaned wires. Always outside, in the snow, in the cold. We were not allowed to go indoors to warm up. The only shelter from rain was beneath technical structures”.

VIOLATIONS OF CULTURAL RIGHTS IN PLACES OF IMPRISONMENT

Violations of the cultural rights of political prisoners constitute a distinct and serious problem requiring dedicated analysis. In 2025, numerous restrictions were recorded, including bans on attending language courses and studying foreign languages; confiscation of textbooks and books in foreign languages – sometimes leading to placement in a punishment cell for possession of such materials (Correctional Colony No. 15) or the removal of relevant sections from prison libraries (Women’s Colony No. 3); prohibition on access to psychology books; confiscation of specific works, including The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn; and a general ban on library use for prisoners designated as “extremists” (Colony No. 17).

Reports also indicated the confiscation of manuscripts written in prison, the systematic destruction of books, and bans on political prisoners participating in cultural activities such as concerts, clubs, and other collective events.

Particular concern arises from cases of persecution for the use of the Belarusian language in places of imprisonment. After release, Łarysa Ščyrakova reported that the prison governor viewed her use of Belarusian as an attempt to “set up the administration”. Local historian and journalist Jaŭhien Mierkis stated that prisoners using Belarusian were placed on “preventive supervision lists” and threatened with punishment cells. It is also known that public activist Vitold Ašurak and artist Aleś Puškin, both of whom died in prison, were subjected to intensified pressure, including because of their principled use of the Belarusian language.

Cases have also been documented of persecution linked to the use of national symbols, including demands by prison authorities that prisoners remove tattoos depicting the Pahonia coat of arms – a national symbol recognised as part of Belarus’s historical and cultural heritage but treated by the authorities as “oppositional”.

TRANSNATIONAL REPRESSION OF CULTURAL FIGURES

The Belarusian authorities continue to pursue repressive measures against cultural figures living in political exile. Such persecution takes the form of new criminal cases initiated in Belarus, trials held in absentia, seizure of property, public defamation, inclusion on lists of “extremists” and “terrorists”, designation of initiatives as “extremist formations”, and pressure on relatives who remain in the country.

THREATS TO LIFE

Since autumn 2020, opposition politician and former Minister of Culture Pavieł Łatuška has been subjected to targeted and systematic pressure by the Belarusian security services. He has already received dozens of threats aimed at forcing him to cease his political activities abroad.

In 2025 alone, there were documented threats of physical liquidation and abduction, attempts to determine his whereabouts through fake journalistic enquiries, and public defamation at the highest level of state authority. After the United Transitional Cabinet [15] was designated a “terrorist organisation” and Pavieł Łatuška was added to the “terrorist list”, he faced direct death threats, a physical attack in Warsaw, an extensive propaganda campaign involving former and current security officials, and intensified pressure from the security services, including threats directed at his relatives.

PRESSURE ON RELATIVES IN BELARUS

Pressure on the relatives of political exiles based in Belarus remains widespread. It includes visits from law enforcement officials, threats, interrogations and other forms of harassment.

After blogger and musician Andrej Pavuk took part in a Pride march in Vilnius wearing a Belarusian police uniform and carrying the official red-and-green state flag, security officers visited his elderly parents. They recorded a “repentance video” with them. The video was later broadcast during a pro-government propagandist’s livestream, Ryhor Azaronak.

Musician Alaksandr Dzianisaŭ reported that security officers visited his mother, warning her that “serious problems” would befall her son if he continued his public activities. Journalist and philatelist Andrej Mialeška, who has been outside Belarus for more than four years, described a search conducted at the home of his ill mother. The relatives of poet and blogger Valery Rusielik (Daroha) have also been questioned about him and his family, without any explanation for the visits.

Other cases are known in which relatives of cultural figures in Belarus have been summoned for questioning, subjected to searches and exposed to other forms of pressure, used as a means of exerting influence over political exiles abroad.

DISCREDITATION AND FAKE COMMUNICATIONS

In September 2025, fake emails were circulated to European politicians and public authorities in the name of political activist, blogger and cultural manager Siarhiej Cichanoŭski. The messages called for cooperation and included specific appeals, among them a letter to the Lithuanian Prosecutor’s Office demanding an investigation into a Seimas member for statements and actions directed against Siarhiej Cichanoŭski and Śviatłana Cichanoŭskaja. Neither Cichanoŭski nor his team had any connection to these mailings.

In November 2025, it was announced that the German Ministry of Culture had allocated €500,000 in funding for the film project Spadčyna (Heritage) by Belarusian director Andrej Pałujan, addressing intergenerational conflict against the backdrop of the revolutionary summer of 2020. Shortly thereafter, Belarusians began receiving fake casting invitations accompanied by questions about their participation in the 2020 protests. The director publicly stated that these messages were fraudulent and had nothing to do with him or his team.

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION IN ABSENTIA, TRIALS AND ALTERATION OF SENTENCES

In 2025, criminal prosecution was recorded against 55 cultural figures living in exile. In most cases, individuals learned of criminal proceedings against them through their inclusion on wanted lists and databases, including public noticeboards titled “Wanted by the Police” and the Russian Federation’s wanted persons database, where Belarusian citizens are listed at the request of Belarusian security agencies. Given the close cooperation between Belarusian and Russian law enforcement authorities, this creates a risk of detention and extradition, including from so-called “friendly” states.

In 2025, comedian Vasil Kraŭčuk was extradited from Russia. He had been sentenced in February 2022 to two years of home confinement. Three months after the verdict, he stopped communicating, was declared wanted, and three years later was detained in Saint Petersburg and extradited to Belarus.

Trials in absentia constitute another distinct form of repression. On 3 June 2025, activist, cultural manager and founder of the monitoring project “Belarusian Hajun”, Anton Matolka, was convicted in absentia under 13 articles of the Criminal Code, including “high treason” (Article 356), and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment and a fine of BYN 84,000 (approximately USD 25,500).

In absentia, activist and cultural manager Alaksandr Łapko was sentenced to 16 years’ imprisonment and fined BYN 231,000 (approximately USD 70,500) under 15 articles of the Criminal Code, also including “high treason”. Artist Vijaleta Majšuk was sentenced in absentia to three years’ imprisonment under articles dealing with the “creation of an extremist formation” (Article 361-1) and “insulting the president” (Article 368).

Courts also conducted proceedings in absentia to alter previously imposed sentences. In cases where cultural figures who had been sentenced to restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility or home confinement left the country and were deemed to have “evaded” their punishment, courts replaced the original sentence with imprisonment in a correctional colony. In 2025, such decisions were taken against poet, musician and translator Mikita Najdzionaŭ, Novy čas editor-in-chief Aksana Kołb, architect Raman Zabieła and history teacher Artur Ešbajeŭ.

DESIGNATION AS “EXTREMIST” OR “TERRORIST”

Following convictions in absentia, cultural figures in exile are, like those convicted inside Belarus, added to official lists of “extremists” and “terrorists”. The practice of designating initiatives operating outside Belarus as “extremist formations” and naming cultural figures as participants in them continues. For the first time, the KGB’s list of organisations classified as “terrorist” has included specific individuals identified as allegedly authorised representatives of those initiatives.

Pavieł Łatuška and Alina Koŭšyk, a journalist and cultural manager, were among those linked to the United Transitional Cabinet, which the Supreme Court of Belarus on 9 July 2025 declared a “terrorist organisation”.

In 2025, those designated as “participants in extremist formations” included actress Kryscina Drobyš (crowdfunding platform Gronka), politician, art historian and writer Zianon Pazniak (“Free Belarus” initiative), art historian Mikita Monič, music critic Alaksandr Čarnucha, cultural analyst Maksim Žbankoŭ (“Democratic Media Institute” project), six members of the Dzieciuki music band and other cultural figures.

The practice of designating cultural initiatives as “extremist formations” and cultural products and social media accounts as “extremist materials” is examined in greater detail in the relevant sections.

INTIMIDATION AND PERSECUTION FOR EVENTS ABROAD

An additional method involves proactively intimidating and subsequently verifying individuals participating in protests and cultural gatherings held outside Belarus. For example, on 27 January, the Investigative Committee announced [16] the identification of 365 participants and organisers of actions abroad on 26 January, the day of the Belarusian presidential election; this figure later increased to “roughly 400”. Before Freedom Day commemorations, analogous threats [17] were conveyed, after which state propaganda outlets reported the identification of 260 participants from the 25 March events.

Research into the consequences of these practices for cultural figures remains ongoing.

CENSORSHIP, BOOK BANS AND OTHER VIOLATIONS OF CULTURAL RIGHTS

Based on our monitoring’s classification of violations, censorship ranked as the second-most prevalent infringement of the rights of cultural figures in 2025 and has consistently remained among the most widely applied forms of repression in recent years. Given that the largest number of documented cases concerns the designation of cultural materials and the social media accounts of cultural figures as “extremist materials” (which we classify as a separate category), it may be concluded that censorship, in its broader cultural and ideological sense, constitutes the most frequently recorded violation over the year.

Performance and exhibition venues remain closed to cultural practitioners included on informal “unreliable” lists. However, isolated cases have been recorded in which authors previously denied permission were approved to perform or exhibit. Cultural figures deemed “banned” continue to be prohibited from publishing in state-run periodicals; previously issued touring licences are revoked; and exhibitions that had already been approved are closed prematurely. At the same time, the list of literature prohibited from distribution on the grounds of threats to national security continues to expand, as does the list of cultural materials designated as “extremist”.

Censorship has affected virtually all spheres of cultural life – literature, theatre, visual arts, museum work, academic education, and even traditional Belarusian culture. Certain subjects have become taboo, and a multi-layered system of ideological censorship has emerged. In the academic sphere, reports indicate that publications are subject to de facto vetting of referenced individuals and that informal lists of authors who may not be cited or researched exist. As a result, censorship – and often self-censorship – within professional communities has intensified significantly over recent years.

Among the documented instances of censorship in 2025 were:

- the inclusion of cultural figures on “blacklists” (stop-lists or lists of “unreliable” persons), resulting in refusals to issue touring licences, exclusion from radio rotation, prohibition on participation in exhibitions and other public events, and a general ban on the dissemination of creative works;

- the cancellation of previously approved events, revocation of touring licences, and removal of works from exhibitions that had already been prepared;

- the confiscation of intellectual property – including authors’ manuscripts and other creative materials – upon the release of political prisoners who are cultural figures from places of imprisonment;

- the inclusion by the Ministry of Information of books in the list of printed publications “the distribution of which is capable of causing harm to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus”.

The practice of designating cultural products and digital resources as “extremist materials” is also examined in this section.

“BLACKLISTS” AND “STOP-LISTS” IN THE CULTURAL SPHERE

Following the full entry into force in 2023 of amendments [18] to the Code on Culture, which substantially expanded state control over the cultural sphere, a key regulatory element became the mandatory prior vetting of participants in cultural events – including performers, authors and organisers – with the involvement of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and other state bodies. As a result, formal legal restrictions have become closely intertwined with the practice of informal “blacklists”, which have become one of the principal tools for excluding ideologically “unreliable” authors from public cultural life.

In practice, organisers of cultural events are generally not provided with explanations for refusals to approve a particular artist’s participation, since decisions are not made based on artistic or professional criteria but rather on the results of external vetting of the individual concerned. A documented case exists, however, in which an official response cited Article 81 of the Code on Culture, stating that the author’s activities “pose a threat to national security and public order” [19].

No official data on the number of cultural figures subject to such personal bans is publicly available. In certain instances, information about such lists becomes public. For example, in February 2023, a “stop-list” of 87 performers prohibited from performing or receiving radio rotation in Belarus appeared in the public domain. During 2025, this list resurfaced in public discourse – including in connection with the organisation of school graduation events – and at the end of the year, the editorial team of the portal CityDog obtained an updated “stop-list” [20] comprising 160 entries (including duplicates and errors in names).

Analysis of this list led to the inclusion of performers who had not previously appeared in it in the monitoring. A significant proportion are Russian artists (Boris Grebenshchikov, Yuri Shevchuk, Maksim Leonidov, Semyon Slepakov, the bands Aigel and Gorky Park, among others), as well as Ukrainian (Artem Pivovarov, Dasha Dorofeeva, the bands Griby and Quest Pistols), Armenian (Jaro & Hanza), Uzbek (Nargiz), Kazakh (Scriptonite), and German (Rammstein) performers. Among Belarusian artists listed are the bands Gryaz, Dai Dorogu!, LSP, Tima Belorusskikh and others.

Restrictions on access to stages and audiences are not limited to formal “stop-lists”. Representatives of the cultural sector report the existence of several levels of informal classification determining the degree to which artists are permitted to engage in public activity.

Certain reports suggest that more than one-third of the members of the Belarusian Union of Artists may be included in “blacklists”, and the total number of effectively banned artists may amount to several hundred. No public register of such individuals exists; however, new names are recorded annually during monitoring.

An illustrative example is Art-Minsk, one of the largest festivals of Belarusian visual art, held annually since 2018 and highly sought after among artists. In 2025, approximately 1,300 applications [21] were submitted (compared to over 1,200 in 2024; over 1,000 in 2023; … and 810 in 2018), of which around 700 were approved. According to artists, applying effectively became a way of testing whether one was subject to a personal ban. Some authors in recent years have refrained from applying, aware that their submissions would not be considered:

“For me, this has been ongoing since 2022, when this law was introduced. At that time, about 30 artists, including myself, were asked not to bring our works [to Art-Minsk] [22].”

CANCELLATION OF CULTURAL EVENTS

In 2025, censorship affected several previously approved cultural events, including exhibitions and concerts. Cancellations and postponements occurred following criticism by pro-government activists, revocation of permits by the Ministry of Culture, and other purportedly “technical” reasons.

On 11 March, the exhibition Belarusian Bestiary, dedicated to mythological figures of Belarusian folklore, opened at the Mastactva Gallery in Minsk. The following day, pro-government Telegram channels accused [23] the authors of conducting a “Satanic sabbath” and “fighting against Christian values”. Two days after the opening, the organisers – Jaŭhien and Jaŭhienija Kot – announced [24] its premature closure for reasons beyond their control and began dismantling the exhibition, which had been scheduled to run until 22 March.

On 19 March, it became known that the traditional festival Sviata Sonca at the Dudutki museum complex, dedicated to Kupała Night, had been cancelled. The touring licence for the event, planned for 21–22 June 2025, was revoked following criticism by pro-government activist Olga Bondareva, who described [25] the festival as a “neo-pagan sabbath with swastikas and runes”. The state news agency BelTA removed [26] a previously published article about the festival from its website. The organisers subsequently secured a new permit, and the Kupała folk-rock festival took place on 14 June, one week earlier than initially scheduled.

On 8 July, a memorial evening dedicated to the Belarusian poet Łarysa Hienijuš was cancelled at the Parason Gallery in Minsk. The event, at which poet and literary scholar Michaś Skobła had planned to speak about the life and work of the dissident writer, became the target of harsh criticism from pro-government Telegram channels [27] and, as a result, did not take place.

On 13 September, at the start of the new theatre season, the premiere of Grimm Sisters, directed by Jaŭhien Karniah, was scheduled to take place at the Minsk Puppet Theatre. However, one day before the performance, it was announced [28] that all scheduled showings had been cancelled due to “technical reasons”. It later emerged that the production had failed to pass review by a state commission, which reportedly deemed it “too dark”.

On 11 October, the Minsk club Reaktor announced the cancellation of a concert by the Homiel-based hardcore band TORF after the touring licence for the event was withdrawn on the day of the concert without explanation. The club’s administration emphasised that the cancellation caused significant harm to both the audience and the venue. The Minsk-based bands Kukly and Broneparovoz had also been scheduled to perform.

On 24 November, the artist Ihar Rymašeŭski announced the cancellation [29] of his exhibition Cardiogram, which had been scheduled to run at the Mastactva Gallery from 25 November to 13 December.

There have also been reported cases of exhibitions by artists Ała Škaradzionak, Valeryj Viadrenka, and others being cancelled without explanation, as well as the removal of works already displayed at the collective exhibitions Viva Kola Art and Colours of the Great Victory.

CONFISCATION OF MANUSCRIPTS

Particular attention should be paid to the practice of confiscating manuscripts and other intellectual output created by cultural figures during their incarceration. Cases of seizure immediately before release were reported by Ihar Karniej (all notes, diaries and notebooks confiscated), Uładzimir Mackievič (all notes and drafts, including texts he described as his best philosophical work), Mikoła Dziadok (approximately 20 kilograms of letters and notebooks), Maksim Znak (manuscripts of literary works, poems, translations and song lyrics), Alaksandr Fiaduta (a screenplay, two plays and two pages of poetry), Aleś Bialacki (manuscripts of two memoirs), Pavieł Sieviaryniec (all written work), Maryja Kalesnikava (two books), Alena Hnaŭk (all correspondence), and Hanna Kurys (sketches and other forms of “prison art”).

The confiscation of authors’ manuscripts constitutes a violation of fundamental cultural rights. In its statement [30] “On the Systematic Confiscation and Disappearance of Authors’ Manuscripts”, PEN Belarus described this practice as “an act of cultural vandalism comparable to the destruction of historical archives or works of art”.

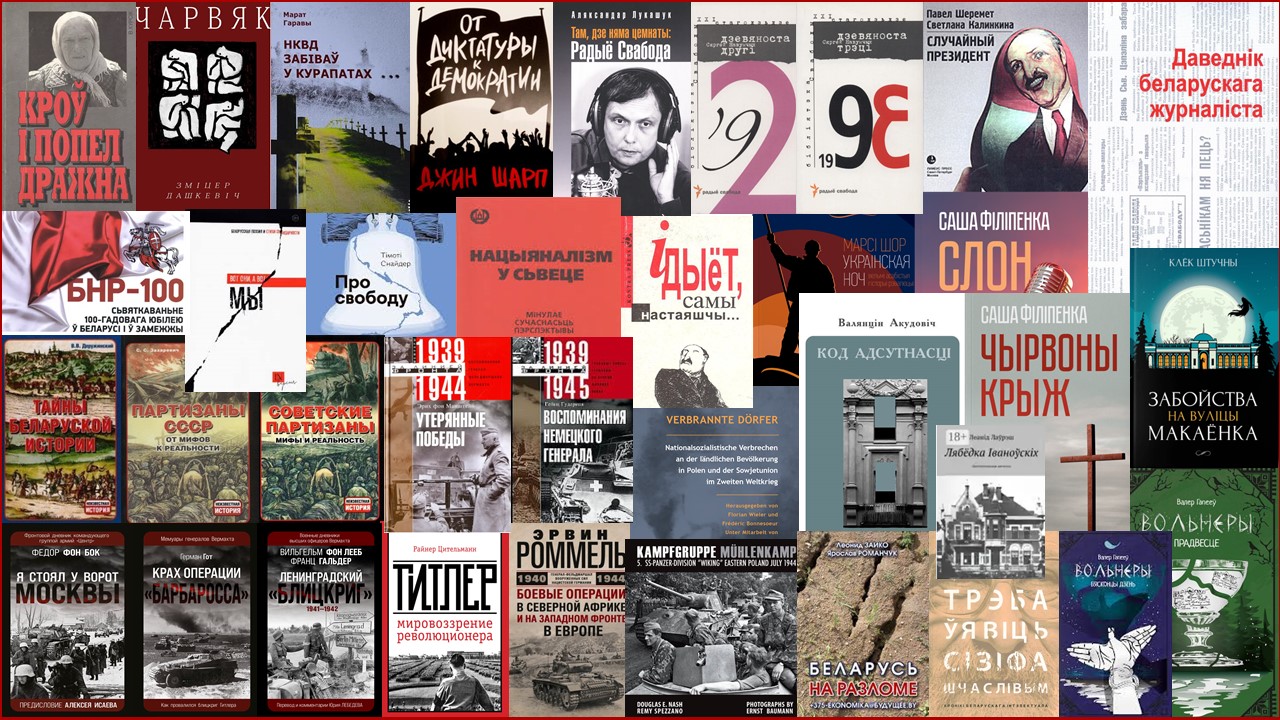

BOOK BANS

Literature is “harm to national interests”

A key instrument of state information control and ideological censorship is the list of printed publications “the distribution of which is capable of causing harm to the national interests of the Republic of Belarus” [31], published on the website of the Ministry of Information. This mechanism became possible following amendments to the Law “On Publishing in the Republic of Belarus” [32], which entered into force on 22 October 2023. First published in November 2024, the list continued to expand steadily throughout 2025.

Members of the Commission for the Evaluation of Symbols, Attributes and Information Products claim that the books included allegedly promote non-traditional sexual relations, pornography, violence and cruelty, drug use, and “subcultures not traditional to Belarusian society” [33].

In 2025, the list was updated 6 times, averaging 32 books per update. A total of 189 publications were added during the year (nominally 190, as Sergey Vereskov’s In the Land of Milk Rivers appears twice).

Among the banned titles are works by Anne Applebaum (Gulag, Iron Curtain); James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room; and widely known works by Iain Banks (The Wasp Factory), Chuck Palahniuk (Lullaby, Invisible Monsters), David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas), and Hanya Yanagihara (A Little Life, To Paradise). The list also includes Naked Lunch and three other novels by William Burroughs, ten works by Irvine Welsh, five by Ryū Murakami, four by Vladimir Sorokin, three by Fredrik Backman, and dozens of other widely read books that address themes of “inconvenient” history, addiction, sexuality, religion, and trauma.

Also featured in the list are the works by Belarusian authors, such as Saša Filipienka’s (Sasha Filipenko) novels The Elephant and The Red Cross, Uładzimir Karkunoŭ’s anthology Here They Are, and Here We Are: Belarusian Poetry and Poems of Solidarity, and Dorota Michaluk’s The Belarusian People’s Republic 1918–1920: At the Origins of Belarusian Statehood.

“Extremist” literature

Additionally, in 2025, 36 documentary, historical and literary books were added to the “List of Extremist Materials” [34], also published by the Ministry of Information. These include works by philosopher Valancin Akudovič (The Code of Absence, One Must Imagine Sisyphus Happy), novelist Valery Hapiejeŭ (Volnery. The Forewarning; Volnery. The Endless Day), Saša Filipienka (The Elephant, The Red Cross), Siarhiej Navumčyk (Ninety-Two; Ninety-Three), Zmicier Daškievič (The Worm), Klok Štučny (Murder on Makajonka Street), and Timothy Snyder (On Freedom), among others.

Since its inception, the method for categorising literature as “extremist”, along with the criteria used, has consistently drawn condemnation from human rights advocates. Nonetheless, the Ministry of Information, the Union of Writers of Belarus, and various law enforcement agencies regularly inspect physical bookstores and digital platforms to detect the circulation of forbidden publications. A notable instance occurred in 2025, when the Mahiloŭ Regional Prosecutor ordered the restriction of access to the online resource kirma.sh, purportedly because it offered for sale content designated as “extremist”, including two books [35].

Libraries must remove books included in the “List of Extremist Materials” and store them in closed collections pending the establishment of an official destruction procedure. Reports also indicate that the KGB has conducted inspections of libraries to ensure that such books are not available in open access to readers.

***

Further information on the two lists of prohibited literature – publications deemed “harmful to national interests” and those classified as “extremist materials” – as well as the legal consequences of such bans, is available on PEN Belarus’s dedicated page Belarus. Banned Books [36]. In 2025, the website also published a special analytical report on pressure on Belarusian books in 2020–2025, entitled The Belarusian book under repression [37].

PRESSURE ON CULTURAL ORGANISATIONS AND COMMUNITIES

In 2025, 44 cases of administrative interference in the activities of cultural organisations and institutions in Belarus were documented.

Despite a decline in the compulsory dissolution of non-profit organisations by 2025, attributed to the segment’s effective depletion, the overarching regulatory authority within this sector has not diminished. Administrative intervention persists, affecting not only the surviving non-profit entities but also commercial cultural enterprises and state-run institutions.

Throughout the year, practices of “normalisation” of creative unions, unequal access to audiences for state and non-state organisations, ideological censorship, personnel purges, inspections, the detention of leaders, and the persistent coercion to close persisted. The practice of designating cultural organisations and initiatives – both those operating in exile and those within Belarus – as “extremist formations” has also continued, entailing serious consequences for their participants and future activities.

INTERFERENCE IN THE ACTIVITIES OF CREATIVE UNIONS

Systemic pressure on creative unions has persisted in Belarus in recent years, and the situation surrounding the Belarusian Union of Artists is among the most illustrative examples. Members have faced bans on participation in exhibitions, manipulation of membership status, direct expulsions, intimidation, and other forms of repressive pressure. Union members have been made to understand that disagreement with the imposed course may result in the loss of the organisation’s independence and its transformation into a structure fully controlled by the state, like the Belarusian Union of Writers. Given artists’ dependence on studio space provided by the Union, such pressure amounts to direct coercion. Official statements by state bodies regarding the “development of the artistic community” stand in stark contrast to actual practice.

A vivid illustration of this policy was the 25th Congress of the Belarusian Union of Artists, held on 23 December 2025, during which the chairperson was elected. Official communications from the Ministry of Culture, whose representatives were present, stated that “key issues of development were discussed” and “strategic decisions were adopted” [38], while entirely disregarding the context of pressure in which the congress took place and the procedural violations that occurred. On the eve of the congress, several participating artists were detained preventively and held at a police station until the vote concluded. An alternative candidate for chair withdrew before the ballot, resulting in the “election” of the sole remaining candidate, Andrej Vasileŭski, Vice-Rector for Administrative Affairs of the Academy of Arts.

IDEOLOGICAL CONTROL AND INSTITUTIONAL PRESSURE ON CULTURAL ORGANISATIONS

State cultural institutions continue to operate under strict ideological control, accompanied by personal attacks on employees, threats of job termination, and the pervasive practice of denunciations. Prominent educational institutions in the cultural field have undergone subsequent personnel purges and the displacement of qualified professionals. Previous occurrences feature the disbandment of the Department of Graphics at the Academy of Arts and the “optimisation” of its theatre faculty. Additionally, a further series of dismissals was reported at the Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts on the eve of the presidential elections.

Participants in private and independent cultural initiatives are regularly summoned for interrogations and “preventive conversations”. State institutions – libraries, museums and bookshops – are informally prohibited from cooperating with non-state initiatives, effectively isolating the latter from public cultural infrastructure.

Searches and pressure targeting independent regional media outlets have been documented, accompanied by public discreditation through state television, where publications by independent media are labelled as “commissioned” or the result of “foreign influence”. In 2025, searches were conducted at the country’s oldest regional outlet, Volnaje Hłybokaje, and its long-serving editor-in-chief, Uładzimir Skrabatun – author of hundreds of local history publications – was interrogated. A report broadcast on the state TV channel ONT [39] accused the outlet of publishing “promotional” articles about Germany funded by the German embassy.

Ideological censorship has also extended to the commercial sector. A notable example involved interference in the activities of the souvenir shop Kaladnaja Krama. Following denunciations by pro-government activists [40], its operations were suspended for selling Christmas ornaments featuring the Belarusian poet and dissident Łarysa Hienijuš. The shop was sealed under the pretext of an inspection for the “rehabilitation of Nazism”. It was only permitted to reopen after removing the “undesirable” items and adding products bearing state symbols to its inventory.

Independent cultural initiatives continue to encounter systemic bureaucratic obstacles. Local authorities refused permission to hold the Energy of Summer festival at the Minsk Sea and did not approve its relocation [41]. In contrast, the Sprava festival has remained on hold for a third consecutive year due to the inability to navigate “various bureaucratic quests and administrative labyrinths” [42]. In December 2025, the independent cultural space Monochrome was forced to close; it had hosted Cinemascope film screenings, classical music concerts and other events.

Another form of pressure remains the use of “anti-extremism” legislation to dismantle cultural infrastructure. After the social media accounts of the independent Minsk-based internet radio station Radio Plato were designated “extremist materials” and the initiative itself declared an “extremist formation”, the project was compelled to switch to a hybrid format and discontinue its original programmes and live broadcasts. Following the detention of its management, the country’s largest non-state ticketing operator, Kvitki.by [43] – a popular online ticket sales platform which had served thousands of events nationwide since 2009 – is in the process of liquidation.

Cyberattacks targeting cultural initiatives have also been recorded. The largest online library of Belarusian literature, Kamunikat.org, was subjected to a major hacking attack that resulted in the deletion of thousands of publications. The authorities had previously included the resource in the list of “extremist materials”, which does not exclude a politically motivated character of the attack.

Pressure extends beyond Belarus’s borders. The European Humanities University in Vilnius has been subjected both to acts of provocative vandalism and to attempts at legal persecution: its website and social media accounts were declared “extremist materials”, and an application was filed with the Supreme Court seeking recognition of the university as an “extremist organisation”. The justification alleged that the university promotes “alternative interpretations” of historical and cultural events and “democratic values”, effectively criminalising academic and cultural autonomy itself.

DESIGNATION OF CULTURAL INITIATIVES AS “EXTREMIST”

Under the pretext of combating extremism, the Belarusian authorities continue to use legislation to persecute cultural and educational activities. Initiatives operating both within the country and in forced exile are systematically designated “extremist formations”, while their websites and other digital resources are declared “extremist materials”.

Such designation entails criminal liability under Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code, regardless of the participants’ location, and renders any interaction with them unsafe – particularly for individuals inside Belarus.

In 2025, a wide range of cultural and educational communities and projects faced such persecution by the State Security Committee (KGB) and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, including:

- On 12 January, the media hub Democratic Media Institute, established in Lithuania in 2023, was designated an “extremist formation”. Among its projects is the Belarusian Content Lab, a competition for independent authors creating media projects related to Belarusian culture and identity.

- On 27 January, the crowdfunding platform Gronka, which was launched in July 2024 to support Belarusian cultural and educational projects, was created.

- On 16 April, the digital platform Vasminoh: Education for Belarusian Children Today and Tomorrow, offering interactive courses in Belarusian language and literature, history and culture, creative writing, geography and other subjects, was designated an “extremist formation”.

- On 27 May, the YouTube channel Žyccio-Malina by Mikita Miełkazioraŭ, a prominent project in the Belarusian YouTube segment that has significantly contributed to the popularisation of the Belarusian language and contemporary culture.

- On 10 July, the Belarusian folk-punk band Dzieciuki, founded in Hrodna in 2012 and known for promoting national identity in their songs, was declared an “extremist formation”.

- On 24 July, the jewellery brand Belaruskicry, founded by Alaksandra Kurkova after the 2020 protests and known for jewellery featuring Belarusian symbols, was designated an “extremist formation”.

- On 2 September, the Telegram chat of concert organisers Org BY, created in 2020 for coordination during the COVID-19 pandemic (although communication had reportedly ceased in 2021), was declared an “extremist formation”.

- On 12 November, the art space Skład Butelek in Barysaŭ, which hosted various cultural events, was designated as an “extremist formation”.

- On 20 November, the independent radio platform Radio Plato was granted the same designation. Since 2018, it had operated as a Minsk-based community radio station for DJs, music producers and participants in the local music scene.

- On 17 December, the historical reenactment club Borysthenis and the media project Da Zoraŭ on Belarusian culture, music and history were designated as “extremist formations”.

FORCED LIQUIDATION OF NON-PROFIT ORGANISATIONS

In 2025, the campaign of forced liquidation of non-profit organisations, initiated in 2021, slowed significantly and became more targeted. This alteration was predominantly driven by the depletion of targets, known as ‘liquidation potential’, following comprehensive purges implemented between 2021 and 2024. Notwithstanding this trend, at least 13 cultural associations, encompassing organisations active in contemporary art, film, local heritage, and tourism, were forcibly dissolved over the course of the year.

Among those liquidated were the Public Association of Contemporary Art Enthusiasts Concept Art, the cultural and educational institution KinoBunker, the Niasviž Tourist Club Vandroŭnik, the Creative Public Association Mastak, the International Foundation for the Revival of the Historic Part of the City of Viciebsk Golden Heritage of Viciebsk, and others.

CULTURE-RELATED MATERIALS DESIGNATED AS “EXTREMIST”

In 2025, at least [44] 356 culture-related materials or social media accounts of cultural figures were added to the “List of Extremist Materials”. In total, more than two thousand materials were designated as “extremist” in Belarus over the course of the year.