October in Europe is a true explosion of various cultural events. Among them was the Revolutionale festival in Leipzig, which this year was held under the theme “Challenges of Conditions.” Participants explored the consequences of social division, authoritarian repression, and totalitarian rule. It is no coincidence that, in addition to German participants, guests from Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, Turkey, and Ukraine were invited to the festival.

Most of the events took place on Wilhelm-Leuschner Square, in the city center, where 35 years ago numerous demonstrations called for a transition from “socialism with a human face” to a democratic system. Incidentally, a monument to Freedom and Unity will soon be built there.

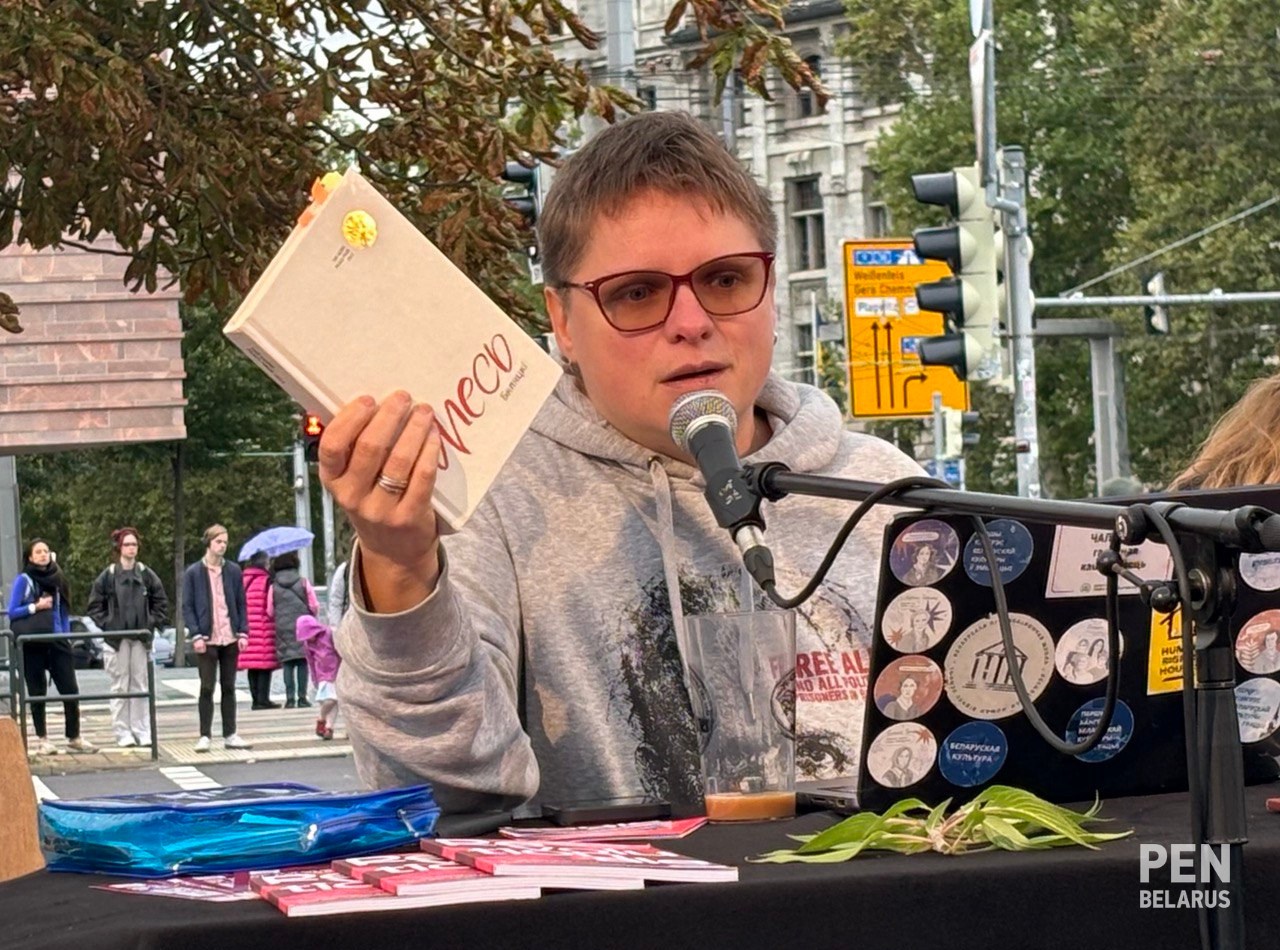

Belarus was represented by PEN members Taciana Niadbaj, Iryna Kozikava, and Dzmitry Strotsev. They spoke about the catastrophic situation of political prisoners, shared works by their colleagues dedicated to Belarusian political issues, and read poems of resistance.

The world was moved by Belarusians and Belarus in 2020. And although times have changed, we have not: we remain as courageous and peaceful as we were then, even though the repressions have continued for four years. Today, we have more than 1,400 political prisoners, and people are detained every day.

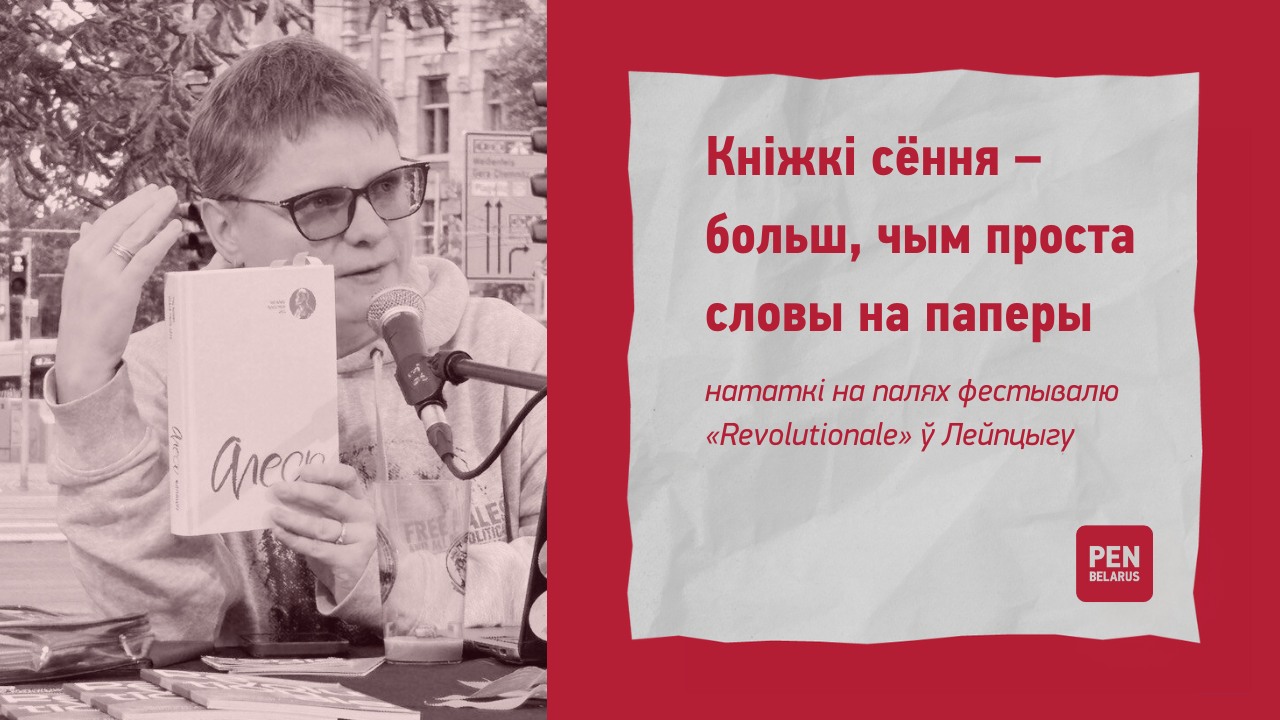

This dramatic situation has given rise to a literature of protest and resistance, filled with powerful reflections. This is especially true of books created in prison. These works are more than just words on paper—they reveal the strong and unbreakable spirit of our people. They hold not merely hope but faith in something better, in the belief that the people’s struggle will ultimately lead to a free and just world.

In the hardest, darkest times, our writers prove that the need for self-expression cannot be imprisoned. It can change society’s thinking, awaken and stir emotions, and evoke deep feelings. Through remarkable new works, Belarusian authors demonstrate again and again that no restrictions on creators can stifle freedom of speech, and that the arbitrariness and ruthlessness of totalitarian power are successfully challenged by the force of a talented pen.

One of the regime’s propagandists recently made a cynical statement about the regime’s attitude toward those political prisoners who were at the forefront of the 2020 revolution. The conclusion was stated openly: if they are ever released, it will only be as part of a major political bargain. And perhaps the main “asset” in this trade will be the Nobel laureate Ales Bialiatski.

Taciana Niadbaj spoke about his work, while translator Tina Wünschmann read several excerpts from the book Ales. Iryna Kozikava shared the story of her brother Maksim Znak’s fate. To applause from the festival stage, poems of resistance by Dzmitry Strotsev and Taciana Niadbaj were also recited.

We asked the translators of Belarusian authors into German who attended the festival and helped our delegation hold the attention of a grateful audience to share their impressions of the Belarusian part of the Revolutionale program.

Andreas Vaahe:

“Everywhere in the world there is a circle of people interested in literature—and through it, they connect with information about the country from which the author or their characters come. Belarusian writers are no exception in this regard.”

When you introduce your friend Dzmitry Strotsev to German readers, what are they most interested in?

“Anyone passionate about poetry is drawn to any new, vivid author. And here, it’s that rare situation when a poet addresses political themes while maintaining his own original poetic language.”

In many cases, though, this pushes authors to abandon poetry and turn to plain polemics…

“That’s true, but Strotsev still manages to preserve reality precisely in his distinctive poetic key, even though he is deeply immersed in a dreadful political situation. I see how strongly this immersion affects him. Before my eyes, his poems are becoming more complex, filled with new techniques, intonations, and vocabulary—the realities have clearly transformed his poetics.”

“By the way, right now I am translating an article by Dzmitry for a popular Berlin literary magazine with the unusual title Language in the Technical Era. In it, he reflects a lot about his creative evolution.”

“But I want to stress again: there are always people who, through poetry and literature, filter social and political processes for themselves, and in them—the everyday life in the most extraordinary colors. I can attest that Strotsev succeeds in reaching such readers, including here in Germany.”

Tina Wünschmann recently introduced the German literary community to Eva Vezhnovets’s novella What Are You After, Wolf?. The book was shortlisted for the International Literary Award for an outstanding work of contemporary foreign literature in its first German translation.

“Right now, there is a very clear interest among my compatriots in Belarusian literature and Belarus itself, so I am working on translating several works and authors at the same time. For example, I am in constant contact with Yulia Tsimafeyeva, Alherd Bakharevich, Sviatlana Ben, Dzmitry Strotsev… I’m preparing to read their poems at Berlin’s Poetry Night on October 30. And a little later, I plan to present the book Ales.”

“I see a positive response to the creativity of Belarusian writers. Today’s festival in Leipzig was no exception.”

Isn’t that simply the courtesy of the hosts?

“I have often witnessed how Germans become genuinely interested in the context of a wide variety of works and, after evenings like this, go online to look up Wikipedia and other sources of information about your country and the events taking place there. For many, these books actually become a key to understanding the situation and the spirit, the moral backbone of the Belarusian people.”

“But I also want to emphasize another fundamentally important point: it is truly gratifying that your newest literature is also admired by the current Belarusian émigré community in exile.”

Thomas Weiler this year received the Paul Celan Prize for translating Alherd Bakharevich’s novel Dogs of Europe. It was precisely during this work that the peaceful revolution took place in Belarus, followed by the repressions…

“It was very interesting to me to see who came to today’s event within the Revolutionale festival, which is not only about Belarus and Ukraine. There are many people here who are keenly interested in their own German culture and history—I mean the Leipzig events of 1989. This is a very subtle and important point: people who were previously unengaged with Belarus want to learn about the dramatic events there and compare them with their own recent and more distant experiences.”

And did today’s presentations by Belarusian writers resonate with the audience?

“My neighbor—a regular German, far removed from literature and politics—came here precisely for this. I asked him for his impression, and he said that yes, he learned a lot from the talks by Taciana Niadbaj, Iryna Kozikava, Dzmitry Strotsev. Their poems and reflections awakened memories; he drew historical parallels… This is how literature builds bridges of understanding between cultures and peoples.”

Tina Wünschmann:

“I’d like to add to what Thomas said: many of the excerpts from Bialiatski’s Ales that I translated, about the events of the late 1980s in Belarusian history and the collapse of the Soviet Union, resonate very closely with Germany’s political realities of that era. Our society also longed for change back then—and it happened. It’s a pity that in your country, freedom lasted only a few years… But today, as we listened and felt, it was clear: Belarusians are still fighting for it, for their dignity. People have not surrendered to the new totalitarianism, which means that a better time will come, and the darkness will be defeated.”

Incidentally, one of the goals of Revolutionale was to create a space for mutual solidarity. The Belarusian participants felt that as well…

Just a day later, all three PEN members were already in Vilnius, taking part in the Belarusian intellectual book festival Pradmova. The interest of visitors in this event once again confirmed: the literature of resistance is in demand, free and liberated speech is alive, it sustains faith in Belarus—and it is doing its work.