Belarus, January – September 2023

Since October 2019, PEN Belarus has systematically documented the violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures. This monitoring report contains statistics and analyses of violations in the field of culture in January–September 2023. It summarises information collected from open sources (80% of cases), through personal contacts (11%) and in direct communication with cultural figures during the study of hidden repression “The Cultural Sector in Belarus in 2022 – 2023. Repressions. Trends” (9%).

NB: For users’ information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources if they are subject to restrictions under the current regulations in the Republic of Belarus. More on the monitoring here.

The main results of the monitoring

Cultural figures behind bars: inhuman and degrading treatment

Arbitrary detentions, criminal and administrative prosecution of cultural figures

Persecution for donations

Censorship: a ban on unloyal artists, restrictions on dissemination of cultural product

State policy in the field of culture

THE MAIN RESULTS OF THE MONITORING

We continue to record violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural figures. The ongoing crackdown and new forms of pressure are becoming less and less visible (public). Still, they are impacting the state of the cultural sphere, activity and creativity of people of culture in Belarus.

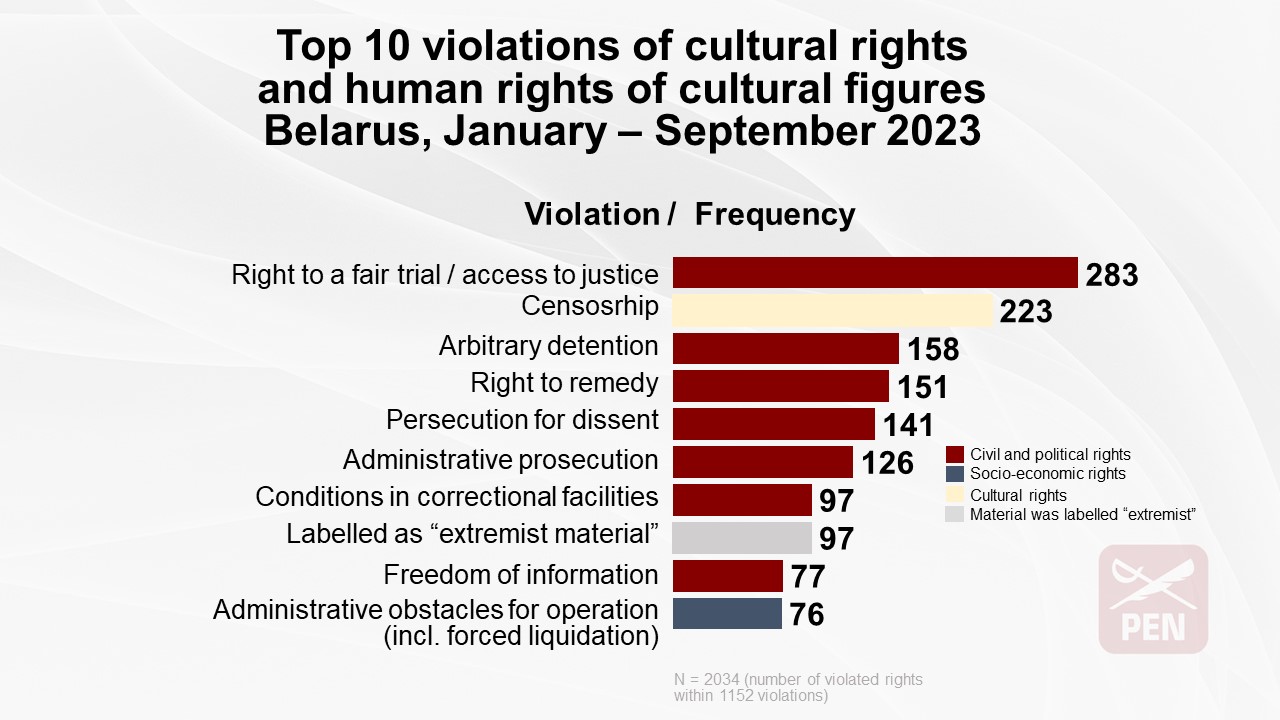

- In January – September 2023, 1,152 violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural workers were recorded in Belarus.

- Violation of the right to a fair trial/access to justice and censorship were the main violations against cultural figures during this period.

- Several cultural figures died behind bars: artist Ruslan Karčauli (in a Hrodna prison), cultural manager and blogger Mikalaj Klimovič (in a Viciebsk penal colony), artist and performer Aleś Puškin (in a Hrodna prison). Human rights activists and the general public attribute these tragic deaths to the conditions of detention and inadequate medical care in closed institutions of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Poet Dzmitry Sarokin died in the Lida District Department of Internal Affairs under unclear circumstances.

- Cultural figures persecuted for political reasons are subjected to inhuman treatment and constant physical and psychological pressure. Transfer to a punishment cell, punitive confinement cell or a cell-type room, stricter prison routines, fresh charges in new criminal cases, and blocking of correspondence and communication with the outside world and families are stable and widespread practices of the penitentiary system. At least 25 people have been behind bars for more than 1,000 days – almost three years.

- As of 30 September 2023, at least 149 cultural figures were in penal colonies, prisons, pre-trial detention centres, open-type correctional facilities or home confinement. 106 of them are recognised as political prisoners.

- 152 cultural figures were arbitrarily detained, some twice or thrice during the analysed period. New criminal cases were initiated against 49 people. 110 people faced administrative proceedings.

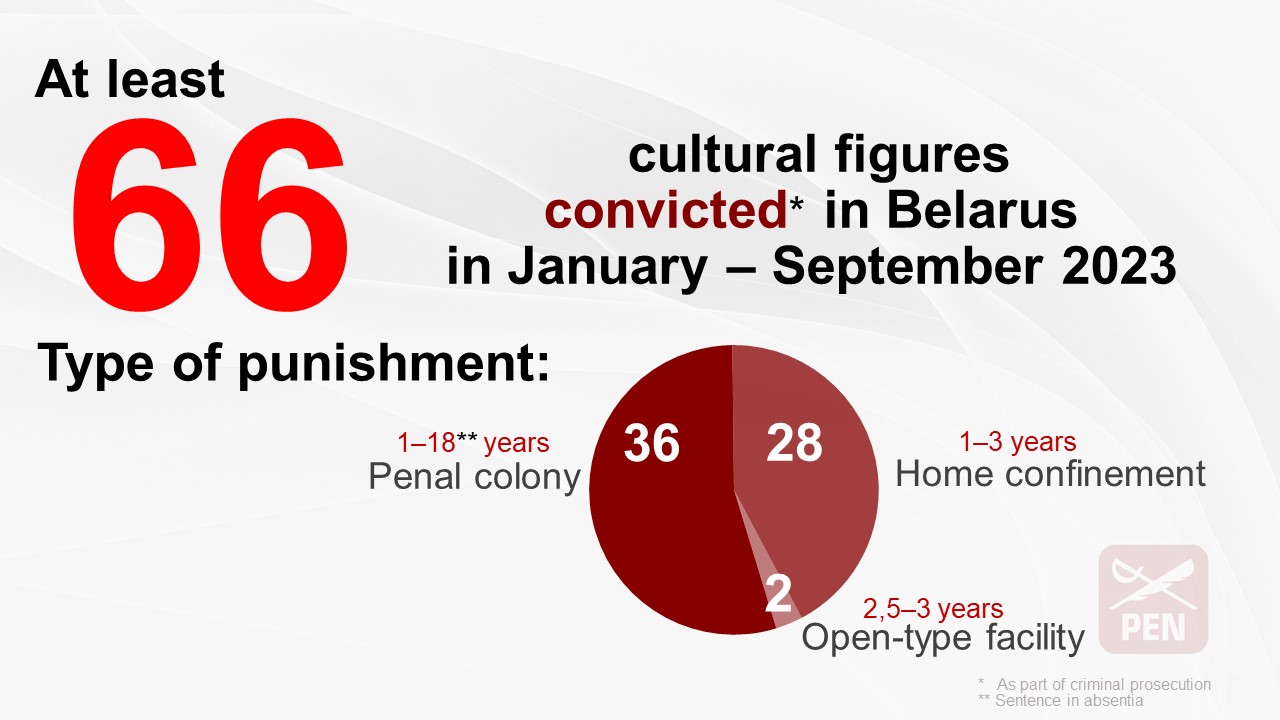

- At least 66 cultural figures were convicted in criminal trials. Almost one in two (29 out of 66) was convicted for participation in peaceful assemblies (protests) back in 2020. The charges were based exclusively on Article 342 of the Penal Code of the Republic of Belarus (organising and preparing actions that grossly violate public order or actively participating in them). 36 cultural figures were sentenced to imprisonment in a penal colony. At least 230 cultural workers have been criminally prosecuted since the end of 2020.

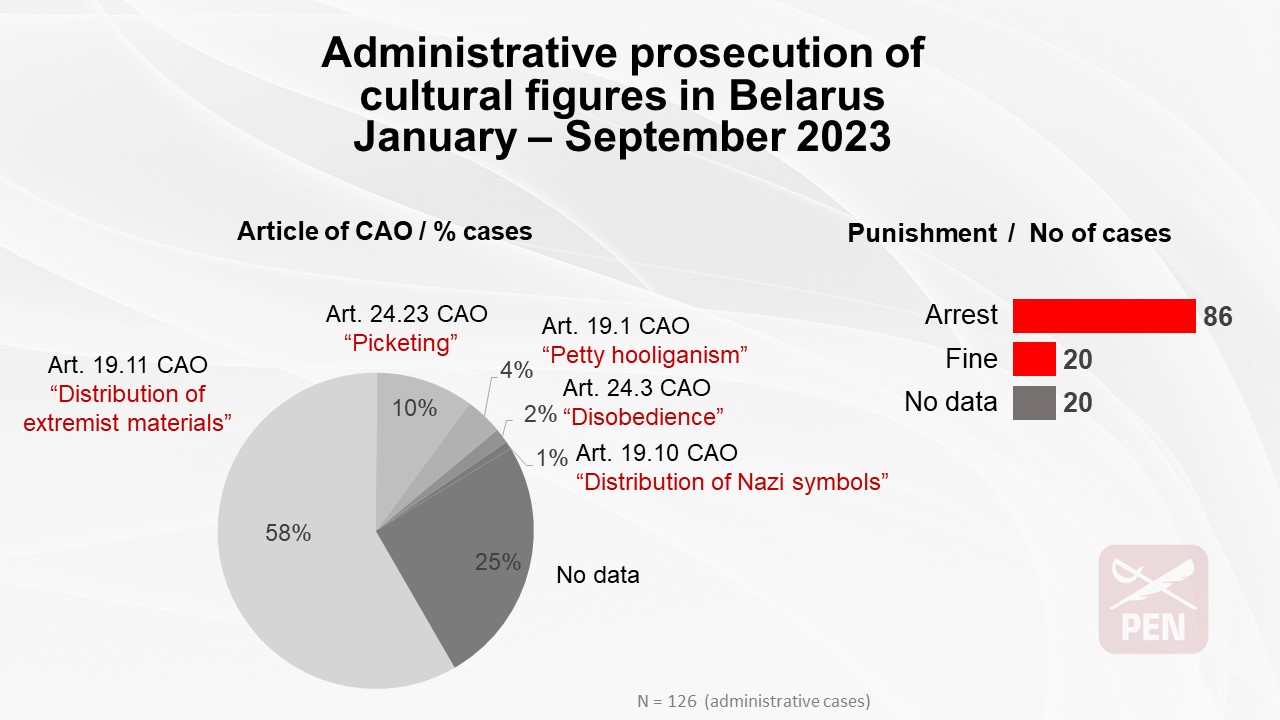

- Information was recorded on 126 administrative cases against 110 cultural figures. No less than one in two cases (58%) was for alleged “distribution of extremist materials” (Article 19.11 in the Code of Administrative Offences “Distribution, production, storage, transportation of information products containing calls for extremist activities or promoting such activities”), i.e. subscription and reposting news from Belarusian independent media outlets. Administrative arrest is the most common punishment for the administrative prosecution of cultural figures (two out of three protocols).

- The Ministry of Internal Affairs included 175 cultural figures (+19 in the previous quarter) in the List of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, foreign citizens and stateless persons involved in extremist activities.” 24 (+1) were included by the State Security Committee in the List of organisations and physical persons engaged in terrorist activities.” The names of another 10 (+2) appear in the List of organisations, formations, and self-employed entrepreneurs involved in extremist activities” as participants in such “formations.” In practical terms, being on these lists means additional discrimination for people.

- Politically motivated dismissals of cultural figures from state-run institutions continue. There were mass detentions of specialists at workplaces with subsequent layoffs. For example, in Q3 2023, at least seven employees of the National History Archive of Belarus were dismissed this way.

- One of the most common practices this year has been the persecution of cultural figures for donations to solidarity funds helping the victims of repression in 2020–2021.

- There is an increasing number of repressions associated with oral communication. This type of repression applies to professional communities. It includes a summons for meetings with officials at the Ministry of Culture, threats and pressure from management, whipping up a hostile attitude towards particular employees, “recommendations” to site curators not to hold certain events and similar techniques. Also widespread is the practice of so-called conversations with citizens at the Ministry of Internal Affairs and KGB stations either through summons or after a preliminary inspection of home premises and equipment (computer, telephone), after which a cultural figure is taken from the home. In the latter case, the procedure can last up to 10 hours, and people do not understand whether they are detained or not, nor do they have the opportunity to contact relatives and a lawyer.

- Another 35 non-profit organisations (+15 in the previous quarter) dealing with dance, local history, ethnic minorities, those working in the field of heritage protection and other areas of culture – were forcibly liquidated. In total, since the targeted campaign to liquidate civil society in Belarus started in late 2020, at least 218 NGOs related to the cultural sphere of Belarus have been subjected to forced liquidation.

- At least 97 culture-related materials (including social media pages of cultural figures) were included by the Ministry of Information in the “National List of Extremist Materials.” The ministry also criminalised some particular chapters in a book for the first time. On 15 August, Minsk’s Centralny District Court labelled as “extremist” the poems “Plyvuć Viatry” (Winds are Blowing) and “Hutarka Staroha Dzieda” (An Old Man is Talking) by a 19th-century classic of Belarusian literature Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič, and the preface by Jazep Januškievič in the book “Selected Works / Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič” – the hundredth volume of the Belarusian Book Collection project, published by Belaruskaja Navuka (Belarusian Science) in 2019. In addition, 22 books – works of fiction, historical or scientific materials – were labelled as “extremist” in 2023. Since March 2021, this number has increased to 33 books.

- Authorities continue blocking Belarusian content and independent information sources. The Ministry of Information again blocked the website of ARCHE, an independent popular science magazine. Access to the website of the Belarusian Council of Culture (designated as an “extremist formation” in June 2022) is limited. The site https://audiobooks.by/, which hosts audiobooks in the Belarusian language and by Belarusian authors, stopped opening from Belarus. The website https://horki.info – an information resource about the Horki, Drybin and Mscislaŭl districts of the Mahilioŭ region with a special section History dedicated to the history of this region – is blocked. Access to the Belarusian online library kamunikat.org is blocked.

- Crackdown on “unnecessary memory”, especially about the national liberation movement and the Polish historical and cultural heritage, is ongoing. In Hrodna, the local authorities removed a memorial about the 1863–1864 [anti-Russian] uprising from the railway station and replaced it with a plaque about Soviet [anti-Nazi] underground fighters. The memorial plaques were removed from the graves of Polish soldiers at the Hrodna military cemetery. Ten tourist stands installed for the 180th birthday anniversary of Eliza Ažeška (Orzeszkowa) (1841–1910), a Hrodna region-born Polish-speaking writer and public figure, have disappeared. In Minsk, a cross erected in memory of Belarusian Roman Catholic priest Vincent Hadleŭski, one of the leading figures in Western Belarus in the 1930s, was removed from the territory of the St. Roch Church.

- The state implements the policy of discriminatory attitude towards the Belarusian language and Belarusian identity, while Russification of the cultural sphere continues in all its sectors.

CULTURAL FIGURES BEHIND BARS: INHUMAN AND DEGRADING TREATMENT

Since this monitoring project started in October 2019 and the 2020 largest protests against the current regime in the history of Belarus, no less than 45 cultural figures, who in one way or another supported the movement for change, have walked out free, having fully served their criminal sentences – between one and three years in a penal colony, 1.5-three years of restricted freedom in an open-type facility or between one and two years of home confinement. However, the number of cultural figures imprisoned for political reasons is not decreasing. More and more people from creative professions are replacing those convicted in 2020/21. Detentions do not stop. As of 30 September 2023, at least 149 cultural figures are in prison due to unfair detentions, arrests and subsequent trials. 106 of them are recognised as political prisoners.

Four cultural figures have died in Belarusian prisons – history promoter and activist Vitold Ašurak in 2021; artist Ruslan Karčauli, cultural manager and blogger Mikalaj Klimovič; artist and performer Aleś Puškin in 2023. The regime did not leave them alone even after death. The farewell rituals for Mikalaj Klimovič (in May) and Aleś Puškin (in July) took place under the supervision of plainclothes “law enforcement” officers, who recorded on camera those who came to say goodbye to the people of culture killed by the regime. The relatives and colleagues were strongly advised to refrain from comments and interviews.

As of writing, at least 25 Belarusian cultural figures have remained in prison for more than 1,000 days. This number includes culture manager, video blogger and politician Siarhiej Cichanoŭski; writer and political activist Paval Sieviaryniec; philanthropist and politician Viktar Babaryka; culture manager Eduard Babaryka; musician and activist Siarhiej Sparyč; dancers Ihar Jarmolaŭ and Mikalaj Sasieŭ; author of prison literature and activist of the anarchist movement Aliaksandr Franckievič; musician and manager of cultural projects, public figure Maryia Kalesnikava; writer, bard and lawyer Maksim Znak; documentary film author and blogger Paval Spiryn; UX/UI designer Dzmitry Kubaraŭ; architect Arciom Takarčuk; history promoter, blogger Eduard Palčys; designer and architect Rascislaŭ Stefanovič; artist and animator Ivan Viarbicki; artist Aliaksandr Nurdzinaŭ; author of prison literature and activist of the anarchist movement Ihar Alinievič; historical reconstructor and activist Kim Samusienka; drummer Aliaksiej Sančuk; author of prison literature and activist of the anarchist movement Mikalaj Dziadok; writer and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava); concert agency director Ivan Kanievieha; documentary film director, journalist Ksenija Luckina; local historian and activist Uladzimir Hundar.

Already back in 2021, reports coming from prisons indicated that all political prisoners wore a yellow tag so that those disloyal to the regime could be segregated. They undergo persecution throughout their entire sentence terms. Prison administrations put them on the preventive register, which entails additional control and deprivations. They place them in a punishment cell and punitive confinement. Political prisoners are deprived of parcels, packages and meetings with relatives. Walking, playing sports and communicating with other prisoners are restricted. Prisons block their correspondence and impose administrative penalties for far-fetched reasons. Political prisoners are summoned for interrogation and subjected to routine searches in cells. Prison administrations provide inappropriate medical care and put pressure on people physically and psychologically in many other ways. Those speaking Belarusian also undergo persecution in prisons due to their language of communication.

The paragraphs below analyse various types of pressure on the cultural figures as political prisoners – the transfer to a cell-type room (prison cell), a stricter prison routine (from a penal colony to a prison, from an open-type facility or home confinement to a penal colony), fresh charges under Article 411 of the Criminal Code (“Malicious disobedience to the requirements of the administration of a correctional institution”), the blockage of the incoming and outgoing correspondence.

- Transfer to a cell-type room

During the analysed period, at least six cultural figures were transferred to a cell-type room, where the routines and conditions are comparable with a maximum-security penal colony: philosopher and methodologist Uladzimir Mackievič (for three months); musician Aleś Papkovič, musician and public activist Maryja Kalesnikava (not fully confirmed); writer and political activist Paval Seviaryniec (for three months); philanthropist and politician Viktar Babaryka, poet, journalist and Polish community activist Andrej Pačobut (Andrzej Poczobut) (for six months). In total, at least eleven cultural workers have already been subjected to this type of persecution.

- Stricter confinement routines

In January, after the prosecutor appealed, the Hrodna Regional Court ruled to replace two years of home confinement with two years in a penal colony for 73-year-old musician and public figure Barys Kučyński. In February, the Škloŭ District Court ordered stricter confinement routines for 66-year-old philosopher and methodologist Uladzimir Mackevič. He was transferred from the penal colony to a prison. In March, following the ruling by the Navapolack City Court, UX/UI designer Dzmitry Kubaraŭ had his confinement changed from the penal colony routines to the prison regime for three years. In May, the Mozyr District Court replaced the restriction of freedom in an open-type facility with one year in a penal colony for the director of the web design studio Hleb Kojpiš. In June, the Škloŭ City Court held a session to change the imprisonment routines for writer and political figure Paval Sieviaryniec. As a result, he was transferred from the penal colony to a prison for three years. In total, at least ten cultural figures have had their prison routines changed to stricter ones.

- Criminal prosecution under Article 411 in the Penal Code

The initiation of new criminal cases for “malicious disobedience to the requirements of the administration of the correctional institution” (Article 411 of the Criminal Code) is another form of persecution within the penitentiary system. In practical terms, it means extending imprisonment terms but also another way to prevent people from being released after having fully served their sentences. That happened again with the publicist and activist Dzmitry Daškevič (the first time was in 2012). On 11 July 2023, he was scheduled to walk out free after 1.5 years in a colony. However, it became known on that day that he was transferred to a remand prison, facing fresh charges under Article 411. Belarusian human rights activists have repeatedly spoken about the arbitrary practice and selectivity of the application of this article by the administrations of prisons and colonies – in particular, “for example, against an undesirable prisoner or for political motives of the authorities“. Authorities have opened new criminal cases against four cultural figures under this article since after the 2020 protests.

- Restrictions on correspondence

Depriving political prisoners (cultural figures) of contacts and support from the outside world (family, friends, people expressing solidarity with them) is one of the most widespread forms of pressure. No logic can explain the rules of prison correspondence. What is known is that letters get restricted selectively. In most cases, letters from close relatives are only relayed to inmates (but not all, even in such cases).

During the analysed period, the monitors regularly spotted the following messages in independent media reports or Facebook posts: “No letters come from him to anyone except his family” (Jaŭhien Merkis); “we know nothing about the state of his health” (Uladzimir Mackievič); “this year I have not received a single letter or greeting” (Ihar Alinievič); “letters come to her, perhaps, only from relatives” (Natallia Dulina); “alas, almost everything went down the drain” (Viktar Bojka), “he doesn’t receive letters – only from his brother” (Uladzimir Bulaŭski). There has been no contact with some political prisoners (cultural figures) for months – not just for days and weeks. Since February (already eight months), the relatives of Maksim Znak and Maryja Kalesnikava have not heard from them. For several months, there has been no information about Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, Viktar Babaryka, Uladzimir Hundar, and Aliaksandr Franckievič. The restrictions on correspondence affect both political prisoners and members of their families, who, for a long time, may be entirely in the dark about what is happening to their loved ones. Belarusian human rights activists tend to classify this type of pressure as torture.

- Other forms and types of pressure on political prisoners (cultural figures)

Cultural manager Uladzimir Bulaŭski could not attend his father’s funeral in April. In June, local historian and journalist Larysa Ščyrakova could not bid farewell to her deceased mother. Imprisoned cultural figures are deprived of meetings with lawyers. The latter, in turn, may be refused meetings with their clients for weeks under various pretexts. As before, there is direct pressure on the lawyers representing the interests of political prisoners (cultural figures). They undergo detentions, administrative and criminal prosecution, unscheduled re-certification, and deprivation of licences. All of these directly violate the right of imprisoned cultural figures to legal assistance. During the analysed period, the Qualification Commission for Defense Attorneys revoked the licenses of lawyers representing the interests of Paval Seviaryniec, Paval Vinahradaŭ and Tacciana Vadalažskaja (lawyer Tacciana Lišankova), Maksim Znak and Paval Belavus (Yury Kozikaŭ), Andrej Pačobut (Aliaksandr Birylaŭ), Siarhiej Cichanoŭski (Inesa Alenskaja).

***

Persecution and psychological pressure do not end with the release of cultural figures from prison. Once released, they face additional controls and restrictions. Former political prisoner, bard and programmer Anatol Chinievič, released in February 2023 after serving his 2.5-year sentence, had to leave Belarus shortly after. He was under constant stress due to visits by police officers at his house (sometimes even at night), summons to the inspectorate, conversations with the local police department and other forms of pressure. Another type of persecution after release is a ban on leaving the country. Irdorath musicians Nadzieja and Uladzimir Kalač, released last April after 2.5 years in a penal colony, faced it. The musicians eventually managed to flee Belarus. However, one must remember that in such cases, leaving the country implies violating the travel ban and, as a consequence, the inability to return to the country due to potential punishment.

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS, CRIMINAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PROSECUTION OF CULTURAL FIGURES

- Arbitrary detentions

For nine months of 2023, the monitors recorded 158 detentions of cultural figures (the same number was for the same period in 2022). They also collected facts of criminal prosecution against 49 people and administrative prosecution against 110 people.

- Criminal prosecution

At least 66 cultural figures were convicted in criminal prosecutions during the analysed period. At least one in two persons (36 people) was sentenced to a penal colony, 28 to home confinement and two people to the restriction of freedom in an open-type facility.

28 cultural figures were convicted solely under Article 342 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (Organising and preparing actions that grossly violate public order or actively participating in them). Cultural manager and activist Uladzimir Bulaŭski’s conviction on 26 May 2023 to two years in a penal colony under Article 342-2 (Repeated violation of the order of organising or holding mass events) was the first case a cultural figure was charged with “repeated violation”. In the realities of Belarusian “justice”, prosecution under these articles is the punishment of disloyal citizens for their participation in the 2020 protests. In essence, it violates the right to freedom of peaceful assembly. All in all, Articles 342 and 342-2 featured in the charges against 38 cultural workers.

The second most frequently applied for criminal prosecution is Article 130 (Inciting racial, national, religious or other social hatred or discord). It appeared in the case files among two to five additional indictment charges during the analysed period. One exception was with PhD in geographical sciences, urban planning specialist Hanna Skryhan, who received two years in a penal colony under Article 130 of the Criminal Code. She stood trial behind closed doors.

Violation of the right to access to justice:

- Courts continue the practice of hearing criminal cases and appeals in closed trials. It deprives defendants of the right to publicity of court proceedings. The public’s right to receive information is also violated.

- Appeals are not satisfied. Almost all verdicts by first-instance courts remain in force. If exceptions do occur, they are the following. In February, the Supreme Court “commuted” by three months the sentence of 17 years in a medium-security colony for the author of prison literature and anarchist Aliaksandr Franckievič. In April, the Supreme Court replaced three years in a medium-security penal colony with three years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility for the moderator of the “FOR THE SINGLE state LANGUAGE in Belarus!” group on the VKontakte social networking platform, researcher Uladzimir Bućkaviec.

- Publicist and activist Alena Hnauk was removed from her trial in a new criminal prosecution. Defendant Ksienija Luckina was not allowed to speak during her trial. Viktar Babaryka, included as a witness in the list of the state prosecutor in the case of Eduard Babaryka, was not questioned during his son’s trial and thus could not testify despite numerous requests from lawyers.

- Administrative prosecution

The monitors collected cases of administrative prosecution of 110 cultural figures, recording 126 protocols against them. The most frequently applied article (at least every three in five cases) is 19.11 (Distribution, production, storage, transportation of information products containing calls for extremist activities or promoting such activities). It envisages punishment for subscribing to independent Belarusian media (added by the regime to the list of “extremist materials”) and sharing news from those outlets. The most common type of punishment is administrative arrest (at least two protocols out of three) for 15 days (almost every second case) or ten days – a little less often (practically every fifth). In approximately one in six administrative cases, courts awarded fines to detained cultural figures. During the analysed period, fines ranged between BYN 111 (~$33) under Article 19.10 of the Code of Administrative Offences and BYN3,700 (~$1110) under Article 24.23 of the Code of Administrative Offences.

Initiating criminal cases for donations [to solidarity funds] is one of the trends of 2023 and one of the most widespread methods of persecuting Belarusian cultural figures at the moment. “Now, as it turned out, many people have suffered because of their donations via Facebook. I have four very close friends who were summoned over this… the authorities started doing this a long time ago, but now the scale has become massive… There are 63,000 people in this database of donations via Facebook. The authorities have begun coming for them almost like in alphabetical order.”

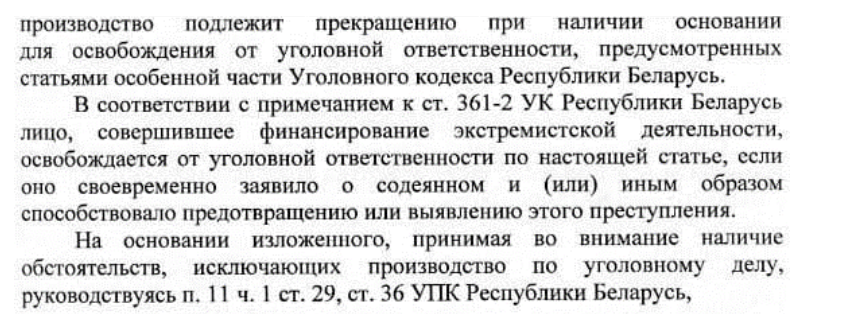

The first cases of persecution of cultural figures for money transfers to BySol, ByHelp and other funds helping Belarusians who suffered from the police violence during the protests were recorded in April of this year. Here is an excerpt from a typical police report: “In a criminal case… under Article 290-1, 4.4.1 2 of Article 361-2 and 4.2 of Article 361-3 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus, concerning the provision of monetary or other means to deliberately support the extremist activities of extremist formations BYSOL, BYHELP, Honest People…” It is characteristic that donations were mainly made in 2020, and the solidarity funds were designated as “extremist formations” in 2021–2022: BySol and ByHelp – on 3 December and 14 December 2021, respectively, “Honest People” – on 4 February 2022. However, it does not prevent the Investigative Committee from initiating criminal cases against Belarusians who donated in 2020. It has become a common practice today. A similar thing happens in situations when cultural figures are charged under Art. 361-1 (Founding an extremist formation or participating in it) – one of the charges brought against cultural manager Paval Belavus. He was sentenced on 11 May 2023 to 13 years in prison, among other things, for allegedly leading the Belarusian Culture Council initiative, designated as an “extremist formation” in June 2022 – seven months after Paval’s arrest. Similarly, private publishing houses are liquidated for publishing “extremist materials” labelled as such by the regime several years after the date of publication. The termination of state registration certificates of entrepreneurs Andrej Januškievič and Dzmitry Kolas led to the closure of the Januškievič and Zmicier Kolas publishing houses.

Back to the context of persecution for donations, cultural figures are invited for a conversation at the KGB (and, most recently, also at the Financial Investigation Department). During those “interviews,” the investigator proposes to close the criminal case against the person if they compensate for the previously made voluntary donation by transferring an amount exceeding X-fold the paid donation to a specified bank account. This is an offer to pay off further criminal prosecution: “… those who were forced to pay some significant money for such a payoff have no guarantees in the future. There is no receipt or some evidence that, for example, 500 euros were paid… 500 euros is the minimum; people pay thousands of euros… They just tell them: “Come there, there’s a cash register. Give this money to the cash register.” They are not given a slip, nothing… They are told that “you will pay, and that’s it, we will leave you alone,” but this makes no sense… it’s just a robbery, and there is no guarantee it won’t happen again tomorrow…” And in most cases, people are given a template to write a “guilty letter,” pay the specified amount (“active repentance”) and leave with a written statement that they are relieved of criminal responsibility:

As of writing, Natalla Žloba, a senior lecturer at the Department of Foreign Literature at Minsk State Linguistic University, has been in pre-trial detention for more than 200 days. On 27 July 2023, she was sentenced to three years in prison under Article 361-2 of the Criminal Code (Financing the activities of an extremist formation) for sending money to the initiatives labelled as “extremist.” On 18 September 2023, dancer and entrepreneur Viktoryja Haŭrylina was sentenced to three years and three months in a penal colony under three articles of the Criminal Code for donations. On 6 December 2022, former English teacher Iryna Abdukieryna received four years in a colony under four charges.

Although this monitoring has collected only about a dozen cases when cultural figures were persecuted for voluntary donations (many people prefer to keep a low profile about it), one can say with certainty that this type of persecution has been on a massive scale.

CENSORSHIP: A BAN ON UNLOYAL ARTISTS, RESTRICTIONS ON DISSEMINATION OF CULTURAL PRODUCT

The conditions in which the Belarusian cultural field finds itself after 2020 are well described in a quote by one of the Pen Belarus’ study respondents: “You understand that there is a favourable or unfavourable situation. Now, the situation is super unfavourable for cultural events of all kinds because – as V.A. once told me – a police officer is always an enemy of a creator. Currently, cultural figures are not in favour in this country. In general, the situation is totally unfavourable for culture.”

In 2023, Belarusian authorities continued to liquidate private publishing houses (Januškievič, Knihazbor, Zmicier Kolas) and non-profit cultural organisations (at least 35 public associations and foundations). They interfered in all sectors of the cultural sphere – literature, music, fine arts, theatre, cinema, heritage and others (see section ADMINISTRATIVE OBSTACLES TO CULTURAL ACTIVITIES. CENSORSHIP AND “BLACKLISTS” OF CULTURAL FIGURES in the semi-annual monitoring report). Works of fiction and scientific literature designated by the “authorities” as “extremist materials” are confiscated from bookstores and libraries. Works of Belarusian literature contemporary classics (in the first place, those published after 2020) are removed from the sale outlets. Russian authors and publishing houses are filling up the Belarusian book market. “Unreliable” musicians from the so-called “blacklist” are refused access to concert venues and radio broadcasts. Actors, directors, and playwrights are prohibited on the theatre stage and cinema. Artists have no access to exhibitions. Writers have no space in state media. Tour guides are not allowed on tourist routes. It is prohibited to popularise the work of disloyal or undesired artists. By banning cultural figures, the system erases the history of them. State-owned cultural and educational institutions remove from their websites the personal pages of cultural figures fired for political reasons – as if they were never there and did not dedicate decades of their creative life to these institutions.

All the measures that the state employs to ban cultural events are “within the law” (“everything they do is technically legit. One can’t challenge it legally” (©)). Everything is regulated (“and crazy things locally”). There are clear rules for everything (” they are very fertile in regulatory activity”). For example, all necessary amendments were made to the Code of Culture. Every event must be approved and certified with a special permit. This requirement does not apply to state-owned organisations. The government has introduced the Register of Cultural and Entertainment Events and the National Register of Tour Guides and Guides/Interpreters, with discriminatory provisions embedded in them. Authorities have established various commissions and councils to exert ideological control over cultural products and their creators. In the past, it would be just enough for tour guides to say: “Let’s meet near the Marat Kazej monument and have a walk” (©). Today, every step has to be approved – an exam, certification, a permit (“Every small thing. Surprisingly, weddings do not require a permit yet” (©)). Exhibitions and lectures must be approved as well (“lectures – yes, poetry readings – no” (©)). By and large, except the state institutions, “still trying somehow to resist this censorship, there is nothing else, nothing is happening” (©), as respondents put it. At first, the organisers tried to request permission for their events (but they were refused). Now, for the most part, they have already stopped asking. “You are going somewhere, and, in principle, you understand that maybe you will come to something forbidden. When you get to some book presentations, you think: how do people manage to do this?” (©).

The state, represented by officials, pro-government propagandists and often plainclothes agents, is engaged in identifying “illegal” cultural events and services. Thus, the Department of Culture of the Minsk City Executive Committee obliged “Minskconcert” to monitor the social networks of cultural and entertainment institutions and report “wrong” parties. The Ministry of Information “initiated the creation of a commission under the Writers’ Union to monitor printed materials distributed on the territory of Belarus.” The government also monitors companies or entrepreneurs which organise excursions. A known case was when a self-employed tour guide faced administrative proceedings for an “illegal” excursion to the Brest Fortress. Representatives of the Ministry of Culture and plainclothes agents attend events in bookstores, libraries and other venues nationwide for the same purpose. In addition, as mentioned in the previous quarterly reports, there are cases when the participants of cultural events were persecuted. For example, in January, police detained the participants of a sightseeing group travelling to the rite “Kaljadnyja Cary” (Three Kings), included in the UNESCO list of intangible heritage. In June, law enforcement agents raided the territory of the Stuly manor house agricultural centre when spectators had come to watch Batlejka – an amateur puppet theatre show. The presence of government “observers” at cultural events is not uncommon today. The visitors to the traditional Catholic festival “Budslaŭ Fest”, which took place this year on June 30 – July 1, noted the police presence in large numbers. The regime controls its citizens.

By limiting independent culture as much as possible, the government makes full use of the resources of the state apparatus, not only from the point of view of using all legislative preferences in the issue of organising events but also to promote its product. This is how “patriotic trips” imposed on schoolchildren to see productions at the Kupala Theater and organised screenings of the propaganda film On the Other Shore (about Western Belarus under Polish rule) take place. Tickets are not purchased but distributed through local executive committees, the Ministry of Culture, the film distribution network, and such pro-government organisations as Belaja Ruś and Belarusian Youth Union. For the beloved by the authorities annual music festival Slavic Bazaar, Lukashenko’s edict provided visa-free entry into Belarus for participants and guests of the festival from 73 countries “to expand the audience.” A ticket to the festival events served as a pass to cross the border.

STATE POLICY IN THE FIELD OF CULTURE

In the third quarter of 2023, the state continued intervening and strengthening control over the cultural sector. New requirements for tour guides and guide interpreters were introduced. Requirements for organisers of cultural and entertainment events became stricter. Amendments were made to the laws “On languages in the Republic of Belarus” and “On the publishing industry in the Republic of Belarus.” A resolution was adopted to change the historical layout of the Brest Fortress – a tangible historical and cultural heritage. The Ministry of Culture is developing a Cultural Import Substitution Program.

Tour guides

On 4 July 2023, the Ministry of Sports and Tourism approved the resolution “On establishing professional and ethical requirements for tour guides and guide-translators.” The requirements include, among other things, “showing respect for the state symbols of the Republic of Belarus, the history of the development of Belarusian statehood“; preventing “subjective incorrect assessments and statements” about the country, “provocative and other negative statements or actions” by tourists; exclusion of “any form of provocation in clothing and appearance.”

Belarusian language

– According to the 17 July 2023 amendments in the Law on languages,

- the right to receive education in the language of an ethnic minority has been abolished. “Other ethnic groups that live in Belarus are entitled to choose their native language as the language of upbringing and instruction” is absent in the new wording of Article 21 of the Law). It is only possible to organise groups to study the language of a national minority in the preschool education system and to study the language and literature of a national minority in the general secondary education system (“Following the wishes of pupils, students and their legal representatives, by decision of local executive and administrative bodies agreed with the Ministry of Education, groups can be created in preschool and general secondary education institutions, in which pupils learn the language of the national minority, classes in general secondary education institutions, in which students study the language and literature of the national minority.” – Article 22 of the amended Law);

- managers and employees of the education system are no longer required to be proficient in Belarusian and Russian languages. This requirement is left only for the teaching staff. Article 21 before amendments read: “Managers and other education system employees must be proficient in the Belarusian and Russian languages.” The amended Article 21 reads:” The teaching staff of the education system must be proficient in the Belarusian and Russian languages.”

Publishing

– On 17 July 2023, amendments were introduced to Belarus’ Publishing Law,

- expanding the list of grounds for re-registration of “publishers and producers of printed publications;

- introducing more reasons for termination and suspension of the state registration certificate;

- expanding the powers of the Ministry of Information, including the termination of the state registration certificate for publishers of printed publications.

Heritage

– On 22 August 2023, the Ministry of Culture adopted the resolution “On Amending the 19 March 2020 Resolution No 23 of the Ministry of Culture,” which approves amendments in the protection zones the tangible historical and cultural heritage located on the territory of the Brest Fortress in the city of Brest, thus allowing to reduce the protection zone by 3 hectares and change the historical layout for the sake of the National Centre for Patriotic Upbringing of Youngsters on the territory of the fortress complex.

Event management

– On 19 September 2023, the Council of Ministers’ resolution On organising and holding cultural and entertainment events tightened access to the organisation of such events by establishing new requirements for organisers included in the Ministry of Culture’s register (the organisers not on the register cannot carry out their activities). Such requirements include:

- “ activities for organising and conducting cultural and entertainment events should be the main activity for the organiser”;

- an organiser, founder, manager of the organiser and (or) specialist “must have entrepreneurial experience or work experience of at least three years related to organising and holding cultural and entertainment events.”

It is also expected that cultural and entertainment events must meet such criteria as “the aesthetic value of the works performed, the artistic integrity and compositional completeness of the event, its artistic design, and the performing skills of the participants.” Besides, to be included in the register, the organiser must, among other things, provide the Ministry of Culture with an extract on offences committed, a copy of the employment record, letters of proof or copies of contracts confirming relevant experience and duration of employment; information about the events carried out over the past three years.

Cultural import substitution programme

– On 12 September, the Ministry of Culture announced the timeline of public discussion of the draft Concept of Developing the National Cultural Space in All Spheres of Social Life in 2024-2026. The “necessity” of the concept “is determined by a certain negative influence of political, moral, aesthetic views and values of foreign origin and cultural products created on their basis, the results of intellectual and creative activity on the worldview, morality, social behaviour of citizens, representing a potential threat to the political, social and demographic security of the Republic of Belarus.” The main threat, according to the authors of the document, comes from Western culture of English and American origin, “affirming the values of individualism, unlimited freedom of creativity, and the promotion of unnatural relations between the sexes and in the family.” The document, among other things, contains the ideas of “traditional value orientations of the Belarusian people“, “traditional Belarusian-Russian bilingualism“, “revision of museum exhibitions dedicated to the period of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth“, “creation of works of fine art by Belarusian authors on state orders“, “protecting the domestic publishing market from foreign competition“, “forming a repertoire policy for professional and amateur creative teams“, a specific selection of “content in the academic subjects “Belarusian Language”, “Belarusian Literature”, “Russian Language”, “Russian Literature”, “World History”, “History of Belarus”, “Social Studies” and other concepts that primarily refer to the Soviet past and demonstrate the servile attitude of officials to the issue of the role of culture for society as a whole.