Main results

Cultural workers as political prisoners

Criminal prosecution of cultural workers

Conditions of detention and the practice of repressions in detention facilities

Persecution of cultural workers for their anti-war stance and support of Ukraine

Persecution of cultural workers who fled the country

The use of anti-extremist legislation to suppress dissent

Pressure on civil society organisations in the cultural sector

Censorship and administrative obstacles in the cultural sector

Copyright infringement

The right to participate in cultural life

Discrimination against the Belarusian language

Pressure on Polish and Lithuanian national minorities

Historical and cultural heritage

State policy in the field of culture

Instead of conclusions: the detention of culture

About the monitoring report

Since October 2019, PEN Belarus has systematically documented the violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural workers. This monitoring report contains statistics and analyses of violations in the field of culture in 2022. It presents the summarised information collected from open sources and in direct communication with cultural figures.

NB: For users’ information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources if, according to current regulations in the Republic of Belarus, they are subject to restrictions.

Belarus is in a state of political crisis. The falsification of the 9 August 2020 presidential election results triggered the largest protests in the history of independent Belarus, leading to the subsequent persecution of protesters. The level of repression against cultural workers is unprecedentedly high. No less than 108 cultural workers are among the political prisoners, and their number is constantly growing, as is the number of unfair court sentences. Tens and hundreds of cultural workers have gone through detentions and arrests, interrogations and trials, searches and fines, colonies and prisons, and many had to leave the country.

Politically motivated dismissals continued in state institutions, with dozens of public cultural organisations forcibly liquidated, clubs and art spaces closed, and independent publishing houses have lost their licenses. In 2022, culture in Belarus existed in the conditions of the suppression of dissent and freedom of speech, censorship and creation of administrative barriers to activities, and discrimination against the Belarusian language, which is the language of the titular nation, as well as distortion of history, and persecution of ethnic minorities. Attempting to preserve and survive, cultural workers combine self-censorship and anonymity inside the country with transferring products of Belarusian culture abroad.

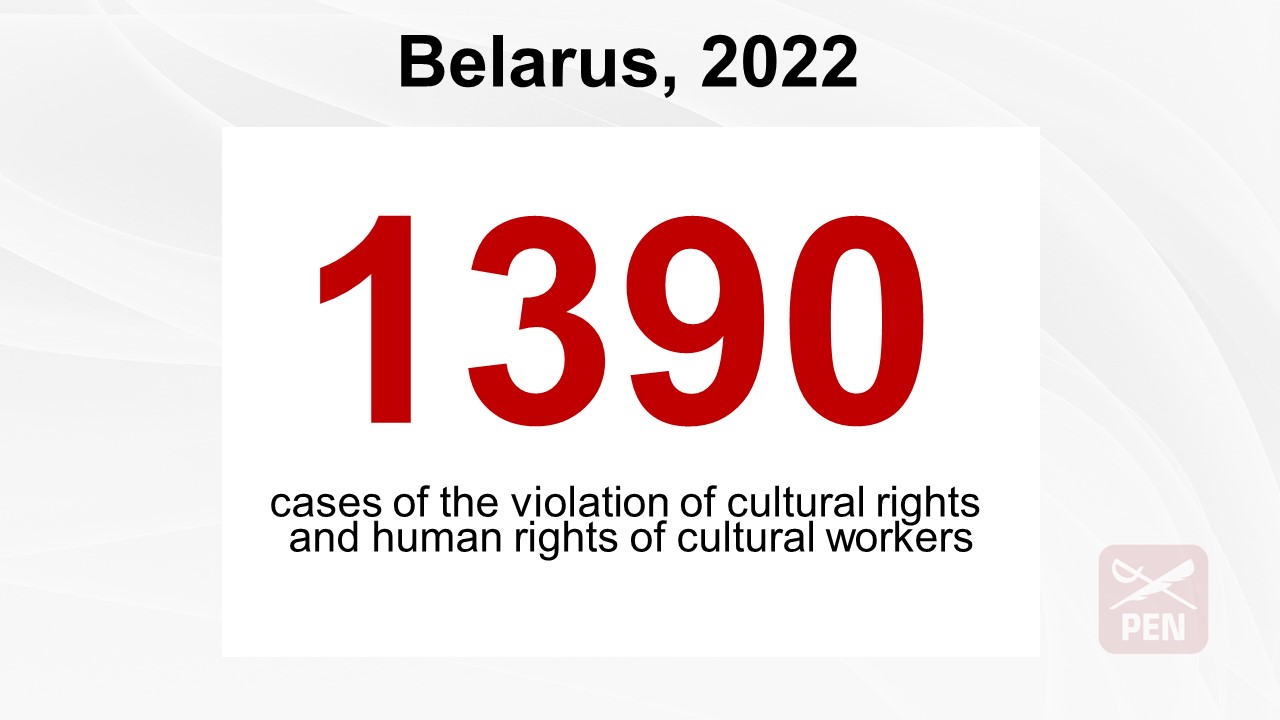

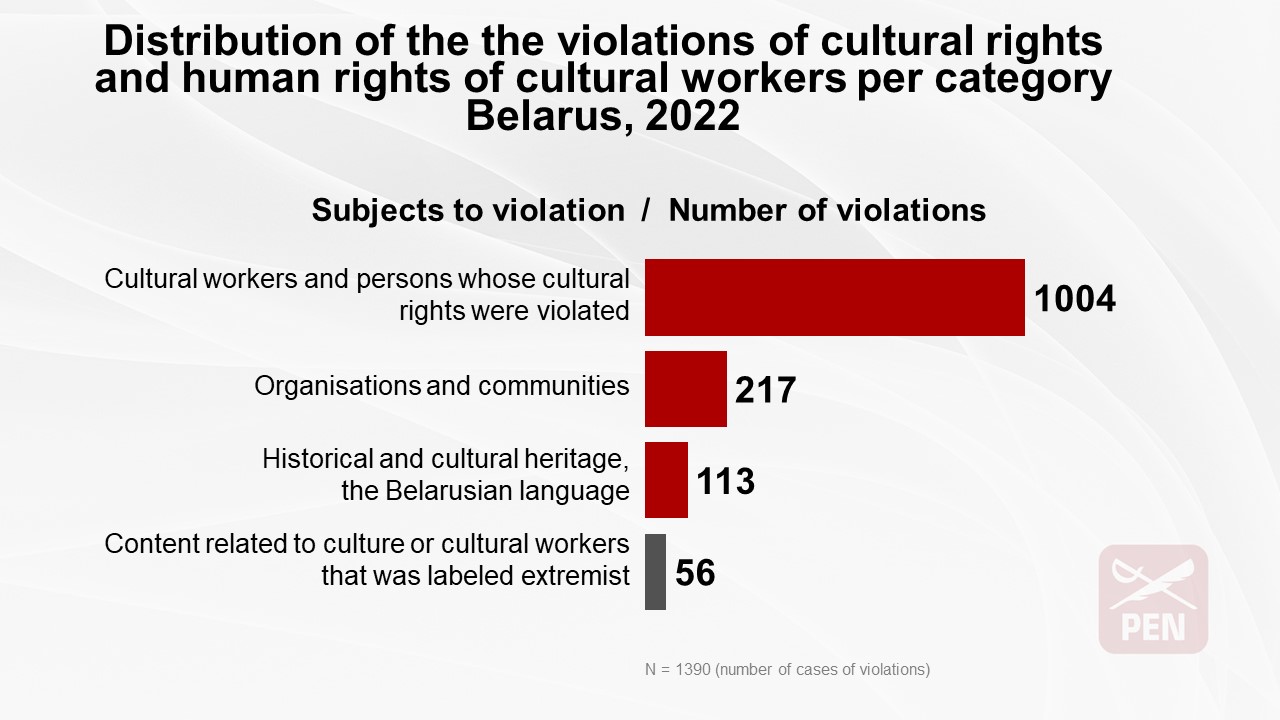

In 2022, we recorded 1,390 cultural rights violations and human rights abuses against cultural workers. Those include:

- 1,004 violations against 518 cultural workers and individuals with violated cultural rights;

- 217 violations against 185 cultural organisations and initiatives;

- 113 violations against historical and cultural heritage sites or the Belarusian language;

- the data also includes 56 sources with content on cultural themes (websites, YouTube channels, articles, clips, books) or those related to cultural workers (their social media accounts) that the Ministry of Information of the Republic of Belarus included in the list of extremist materials.

NB: Due to changes in the research methodology, this report does not present the comparative dynamics of violations for 2020–2022. In 2022, we expanded the definition of cultural workers by including teachers and foreign language instructors and added the topic “culture of memory.” At the same time, we stopped including the forced departure of cultural workers from Belarus in the general statistics of violations. Considering the mass nature of the phenomenon, we classified it as a current trend.

THE RIGHT TO A FAIR TRIAL / ACCESS TO JUSTICE tops the list with 382 instances of violation. In 2022, this violation occurred more than once against 201 cultural workers and 72 organisations in the Belarusian cultural sector.

For the third year in a row, Belarus was a country of courts. Trials in criminal and administrative cases against politically persecuted people resembled a production line. By the end of 2022, we knew of 94 criminal trials against 91 cultural workers who as a result were sentenced to correction in a penal colony, restriction of freedom in an open-type correctional facility (“khimiya” [1]) or put under home confinement (the so-called “domestic khimiya” [2]). These punishments often came together with orders to pay monetary compensation to the state authorities or “injured” members of the security forces, as well as confiscation of property, mainly mobile phones and laptops. We also learned about 150 administrative proceedings against 106 cultural workers, resulting in at least 1,670 days, or more than 4.5 years, of arrest and 24,010 BYN in fines (approximately USD 9,000).

Belarusian trials violate justice administration standards: lasting a few minutes, via video link, with police officers under pseudonyms, with judges rejecting the majority of defence motions. During the year 2022, cultural workers were subject to administrative procedures, mainly for their participation in anti-war protests and use of Belarusian (white-red-white) or Ukrainian symbols, or “an unauthorised mass event, picketing” (Article 24.23 of the Code of the Administrative Offences of the Republic of Belarus) and for reposting content from Belarusian independent media outlets, or “distribution of extremist materials” (Article 19.11). If it was not possible to convict a detained cultural activist under one of those articles, then authorities applied such charges as “disobedience to police” (Article 24.3) or “disorderly conduct” (Article 19.1). Here is an extract from a police report that led to the arrest of a musician for 14 days: “During a conversation in his office, he unreasonably began to behaving aggressively, shouting and using obscene language, intentionally striking the chair at least once, and did not react to requests to calm down.” In numerous cases, court hearings in administrative cases took place without prior announcement of a hearing’s date, time or location.

One of the standard practices in criminal proceedings was to hold trials behind closed doors “in the interest of protecting state secrets and other legally protected secrets.” Such a practice prevented relatives, the media and the interested public from being present in the courtroom and consequently having an understanding of the charges, the parties’ positions and the fairness of the sentence. It also deprived the defendants of moral support.

Another practice affecting the right to a fair trial and access to justice in 2022 was a higher number (seven) of sentence enhancement trials against cultural workers.

Appeals do not lead to the reviews of court decisions. We know of only one case of a review. In October 2022, the Supreme Court considered an appeal against the sentencing of librarian Julia Laptanovič, eventually reducing her sentence from five years to four years and nine months and reducing the fine by almost 1,000 BYN (from 7,650 BYN initially).

In 2022, courts in Belarus forcibly liquidated dozens of non-profit cultural organisations. We know about four appeals against court decisions, none of which were satisfied.

ARBITRARY DETENTIONS

In 2022, we recorded 213 arbitrary detentions of 201 cultural workers. 103 detentions led to administrative proceedings, while 66 led to criminal prosecution. As a result of 15 detentions, cultural workers were released either on the same day or after three to five days; we do not know whether they were held administratively liable. We have no information about the outcome of another 29 detentions that did not result in a quick release.

PERSECUTION FOR DISSENT

In 2021, persecution for dissent topped the ranking of violations. It dropped to third place in 2022 with 197 cases against 178 cultural workers. The change happened not because the scale of persecution was smaller, but because we applied a modified classification of violations in our monitoring work. In 2022, we introduced the notion of administrative persecution, which includes all cases of persecution for dissent that ended with administrative offence reports. At the same time, we started incorporating politically motivated dismissal and demotion, reduced teaching hours, expulsion from educational institutions, “preventive talks”, and summoning for questioning. The Persecution for Dissent category also includes actions against cultural workers who fled the country, namely putting them on an international wanted list, the destruction of an apartment, searches and confiscations of property without subsequent detention, and detentions, the outcome of which are unknown.

The 2022 monitoring report contains information on the following:

- 81 dismissals / non-renewals of contract,

- 56 searches in the houses of cultural workers,

- 32 cases of asset forfeiture,

- 3 deportations.

However, given the current political situation in the country, all categories of violations against cultural workers documented by this monitoring (except for copyright issues) could be regarded as persecution for dissent. Detention, administrative/criminal persecution of cultural workers, denial of quality legal assistance, deportation, “special” conditions of confinement, censorship, author “blacklists”, etc., etc. in essence are forms of persecution for dissent.

THE RIGHT TO LEGAL AID (PROTECTION)

This type of violation ranks 4th with 168 cases against 119 cultural workers. The trend systematic violations of the right to legal assistance in criminal and administrative proceedings, which started in 2020 and 2021, continued. The most common recorded instance of violation is the practice of administrative proceedings, in which the lawyer’s role remains ceremonial.

There are also cases when attorneys are denied meetings with their detained clients, or the time spent with them is reduced to a few minutes. The practice of revoking the licences of lawyers who defend political prisoners continues. The following lawyers defended cultural workers who turned political prisoners in 2022, but did not pass the attestation procedure on the grounds of alleged “systematic violations of the law” or “inability of a lawyer to perform professional duties due to insufficient qualification“: Julia Jurgilevič (Aleś Puškin), Maryja Kolesava-Hudzilina (Eduard Palčys), Vital Brahiniec (Uladzimir Mackievič, Aleś Bialiacki), Uladzimir Pylčanka (Maryja Kaliesnikava, Eduard Babaryka, Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava)), Viktar Mackievič (Viktar Babaryka, Siarhiej Cichanoŭski, Ihar Alinievič, Aleś Bialiacki).

Because of the pressure exerted on lawyers, such as the revocation of licences or administrative and criminal prosecution of lawyers themselves, we noticed an increase in cases of lawyers refusing to defend political prisoners.

ADMINISTRATIVE OBSTACLES TO IMPLEMENTING ACTIVITIES / LIQUIDATION OF ORGANISATIONS

Our monitoring team obtained information on 150 cases of this type of obstruction concerning 133 organisations and communities in the country’s cultural sector. The number includes 75 instances of forced liquidation and 75 cases of ad-hoc inspections by the Ministry of Justice, refusal to issue a touring certificate, cancellation of events, orders to suspend activities, refusal to register, orders to close down, etc.

CULTURAL WORKERS AS POLITICAL PRISONERS

According to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, as of 31 December 2022, there were 1,446 political prisoners in Belarus [3]. This number includes 108 cultural workers: 41 are serving criminal sentences in penal colonies, 7 have their freedom restricted in open-type correctional facilities (“khimiya“), 14 are in prisons, 45 are in pre-trial detention centres of the Ministry of Interior and KGB waiting for either trial or transfer to places of serving their sentences, 1 is under house arrest.

The following cultural workers are in the colonies: architect Arciom Takarčuk (sentenced to 3.5 years); singer, songwriter and IT specialist Anatolij Hinievič (2.5 years); concert agency director Ivan Kaniavieha (3 years); documentary filmmaker and blogger Paval Spiryn (4.5 years); UX/UI designer Dzmitry Kubaraŭ (7 years in a reinforced regime); drummer Aliaksiej Sančuk (6 years in a reinforced regime); culture manager Mia Mitkievič (3 years); writer and public figure Paval Sieviaryniec (7 years in a reinforced regime); dancers Ihar Jarmolaŭ and Mikalaj Sasieŭ (5 years in a reinforced regime); philanthropist and politician Viktar Babaryka (14 years in a reinforced regime); actor Siarhiej Volkaŭ (4 years in a reinforced regime); musician Paval Larčyk (3 years); designer and architect Rascislaŭ Sciefanovič (8 years in a reinforced regime); musician and DJ Artur Amiraŭ (3.5 years in a reinforced regime); history and social studies teacher Andrej Piatroŭski [4] (1.5 years); poet, bard and lawyer Maksim Znak (10 years in a reinforced regime); musician and manager of cultural projects Maryja Kaliesnikava (11 years); musicians Uladzimir Kalač and Nadzieja Kalač (2 years each); writer, musician and author of the “Our History” (Naša Historyja) magazine Andrej Skurko (2.5 years); author of the music project and director of the print shop Arciom Fiadosienka (4 years); history re-enactor and activist Kim Samusienka (6.5 years); author of texts for the magazines Naša Historyja and Arche Andrej Akuška (2.5 years); musician and activist Siarhiej Sparyš (6 years); non-fiction Internet author and blogger Paval Vinahradaŭ (5 years); poet, translator and journalist Andrej Kuźniečyk (6 years); architect Ivan Paršyn (2 years); writer and activist Aliena Hnaŭk (3.5 years); jeweller and history re-enactor Michail Laban (4 years); writer and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava) (8 years and 3 months in a reinforced regime); author and editor of the Wikipedia Paval Piernikaŭ (2 years); former teacher of the Belarusian language and literature Emma Sciepulionak (2 years); philosopher, methodologist and journalist Uladzimir Mackievič (5 years in a reinforced regime); librarian Julija Laptanovič (4 years and 9 months); publicist, author of prison literature and activist Dzmitry Daškievič (1.5 years); local historian and traveller Ihar Haluška (2.5 years); writer, translator and literary critic Aliaksandr Fiaduta (10 years in a reinforced regime); administrator of the cultural and historical Telegram channel Rezystans Mikita Sliapionak (3 years in a reinforced regime); artist Hanna Kisialiova (1.5 years); Danuta Piarednia, a student of Roman-Germanic philology, expelled from the Kuliašou Mahilioŭ State University (6.5 years).

The following cultural workers are serving criminal sentences of restriction of freedom in an open-type correctional facility: director Ihnat Sidorčyk (sentenced to 3 years); designer Maksim Taccianok (3 years); film actor Dzianis Ivanoŭ (2 years); researcher at the Centre for Research of Belarusian Culture, Language and Literature of the Academy of Sciences Aliaksandr Halkoŭski (1.5 years); web design studio director Hlieb Kojpiš (2 years); cellist Illia Hančaryk (4 years); cultural project manager, sociologist Tacciana Vadalažskaja (2.5 years).

Detained in prisons: artist Aliaksandr Nurdzinaŭ (sentenced to 4 years in a reinforced regime colony); artist and cartoonist Ivan Viarbicki (8 years and 1 month in a reinforced regime); author of prison literature, anarchist activist Mikalaj Dziadok (5 years); history promoter, blogger Eduard Palčys (13 years in a reinforced regime); author of prison literature, anarchist activist Ihar Alinievič (20 years in a reinforced regime); cultural manager, video blogger, politician Siarhiej Cichanoŭski (18 years in a reinforced regime); the artist Aleś Puškin (5 years in a reinforced regime); local historian and activist Uladzimir Hundar (18 years in a reinforced regime); fiction writer and journalist Siarhiej Sacuk (8 years); street artist and IT specialist Dzmitry Padrez (7 years in a reinforced regime); architect Aliaksiej Parecki (3 years); DJ and event host Kiryl Žaludok (1 year); cultural managers Paval Mažejka (from 30.08.2022) and Siarhiej Makarevič (from 04.11.2022).

Cultural workers put on remand by the Interior Ministry and the KGB: cultural manager Eduard Babaryka (from 18.06.2020); poet and member of the Union of Poles in Belarus Andrzej Poczobut [5] (from 25.03.2021); author and editor, political scientist and analyst Valieryja Kasciugova (from 30.06.2021); literary scholar, researcher of the history of Belarusian literature, essayist and human rights activist, Nobel Peace Prize winner Aleś Bialiacki (Ales Bialatski) (from 14.07.2021); videographer and cover-performer Hlieb Hladkoŭski [6] (from 30.09.2021); photographer and journalist Gennady Mozheiko (from 01.10.2021); founder of Symbal.by, cultural project manager Paval Bielavus (from 15.11.2021); archivist, cultural historian Vaclaŭ Areška [7] (from 19.04.2022); former director of the event agency KRONA Siarhiej Huń (from 03.06.2022); artist Hienadź Drazdou (no information); singer Meryem Herasimienka [8] (from 04.08.2022); Andrej Žuk, owner of Banki-Butylki bar (from 04.08.2022); actor, casting director Viktar Bojka [9] (from 28.08.2022); local historian and journalist Jaŭhien Mierkis (from 13.09.2022); philologist, Italianist Natallia Dulina (from 03.10.2022); local historian and journalist Aliaksandr Lyčaŭka [10] (from 06.10.2022); musicians Uladzimir and Dzmitry Karakin (from 13.10.2022); tour guide and researcher Valieryja Čarnamorcava [11] (from 18.10.2022); musician Aliaksiej Kuzmin (from 26.10.2022); documentary filmmaker Larysa Ščyrakova (from 06.12.2022). Also author of prison literature, anarchist Aliaksandr Franckievič (sentenced to 17 years in a strict regime colony); artist and interior designer Kanstancin Prusaŭ (3.5 years in colony); sound engineer Vadzim Dzianisienka (2.5 years); bass player Viktar Katoŭski (3 years); DJ Ihar Falievič (2 years); librarian Julija Čamlaj (2 years); musician Uladzislau Pliuščaŭ (3 years); photographer Aliaksandr Kudlovič (2 years); digital artist Viktar Kulinka (3 years in a reinforced regime colony); designer Maryna Markievič (2.5 years); documentary film director and journalist Ksienija Luckina [12] (8 years); poet, journalist and media manager Andrej Aliaksandraŭ [13] (14 years) musician Siarhiej Daliviel (2 years); musician Kryscina Čarankova (2,5 years); teacher-artist Andrej Raptunovič (4 years); poet, producer and blogger Uladzislaŭ Savin (10 years in a reinforced regime); designer and photographer Dzianis Šaramieccieŭ (2 years); former history teacher, librarian and journalist Edhar Šyrko (3 years); light artist Vadzim Vasilieŭ (12 years in a reinforced regime); musician Siarhiej Nikiciuk (3 years); former English teacher Iryna Abdukieryna (4 years); writer Aliaksandr Novikaŭ (2 years); participant of folk arts festivals Aliaksiej Viačerni (1 year and 9 months); photographer Valieryj Klimienčanka (1.5 years).

The Chairperson of the Union of Poles in Belarus, Andżelika Borys, was transferred to house arrest on 25 March after one year in pre-trial detention. She remains a political prisoner.

Along with 108 political prisoners, at least 17 other cultural workers [those we know about] are in criminal detention: DJ Vitali Kaliesnikaŭ (in colony); history re-enactor Vadzim Šylko (in prison); graphic designers Uladzimir Jaršoŭ (in colony) and Siarhiej Stocki (no information); musician and IT specialist Vadzim Hulievič (in pre-trial detention); literature writer and bard Aliaksiej Ilinčyk (in pre-trial detention); illustrator Vadzim Bahryj (no information); musician Jaŭhieni Hluškoŭ (in pre-trial detention); children’s writer and teacher Dzmitry Jurtajeŭ (in pre-trial detention); cultural manager and director of the initiative “Majontak Padarosk” Jury Mieliaškievič and their financial director Dzmitry Karabač (in pre-trial detention); graduate student of history at Belarusian State University Jury Ulasiuk [14] (in pre-trial detention); history teacher Siarhiej Koziel [15] (in pre-trial detention); cultural scientist and etiquette expert Aksana Zareckaja [16] (in pre-trial detention). And serving a home confinement sentence: Rehina Lavar, the creator of Iŭje’s Museum of National Cultures; Jury Zialievič, former director of the Pružanski Palacyk museum; and Mark Biarnštejn (Bernstein), author, editor of Wikipedia and IT expert.

We do not have information about the whereabouts of the following cultural workers sentenced to the restriction of freedom under home confinement: designer Tacciana Minina; comedian Vasil Kraŭchuk; librarian and tour guide Iryna Koval; comedian, art director and presenter Aliaksandr Tolmačaŭ; ceramist Anastasija Malašuk; craftswoman and administrator of the “Alpha Business Hub” space Alesia Kureičyk; teacher of the Belarusian language and literature Halina Tarnoŭskaja; ceramist Natallia Karniejeva; local historian and guide Ihar Chmara; architect and musician Aliaksandr Kucharenka. The sentences handed down against designer Alina Kaŭtunoŭskaja and architects Tacciana and Ihar Kaliesnik are still unknown.

Due to the difficulty in obtaining information, the consequences of reprisals against some cultural workers are unknown. During 2022, we recorded the following detentions, the results of which we do not know: musicians Kanstancin Zimnicki (detained in February) and Andrej Zadziarkoŭski (May); history teacher Andrej Darachovič (May); history re-enactor and owner of the karaoke bar “Šum” Aliaksiej Hurski (June); an employee of the Maslennikau Regional Museum in Mahilioū Dzmitry Žuraŭski (June); manager of cultural projects and activist Dzmitry Bandarčuk; director and founder of the tourist company “Viapol” Halina Patajeva (August); musician Alieh Samsounaŭ (September); writer and engineer Vadzim Kruk (October); photographer Ruslan Mazanik (October); musicians Andrej Havaruška and Aliaksiej Varancoŭ (October); photographer Andrej Salaŭ (October); singer Antanina Valkava (November); historian and teacher Vitald Jermalionak (November); festival organiser Siorhiej Sadoŭski (December); history teacher Vitali Mahučaŭ (December); photographers Varvara Miadzviedzieva and Paval Miadzviedzieŭ (December).

CRIMINAL PROSECUTION OF CULTURAL WORKERS

From November 2020 to late 2022, at least 164 cultural workers were convicted in criminal trials, eight of them more than once: literary scholar and activist Aliena Hnaŭk – three times; author of texts for Naša Historyja and Archemagazines Andrej Akuška, musicians Uladzislaŭ Pliuščau and Aliaksandr Kazakievič, local historian and activist Uladzimir Hundar, literary scholar and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava), poet, producer and blogger Uladzislaŭ Savin and librarian Julija Laptanovič – twice.

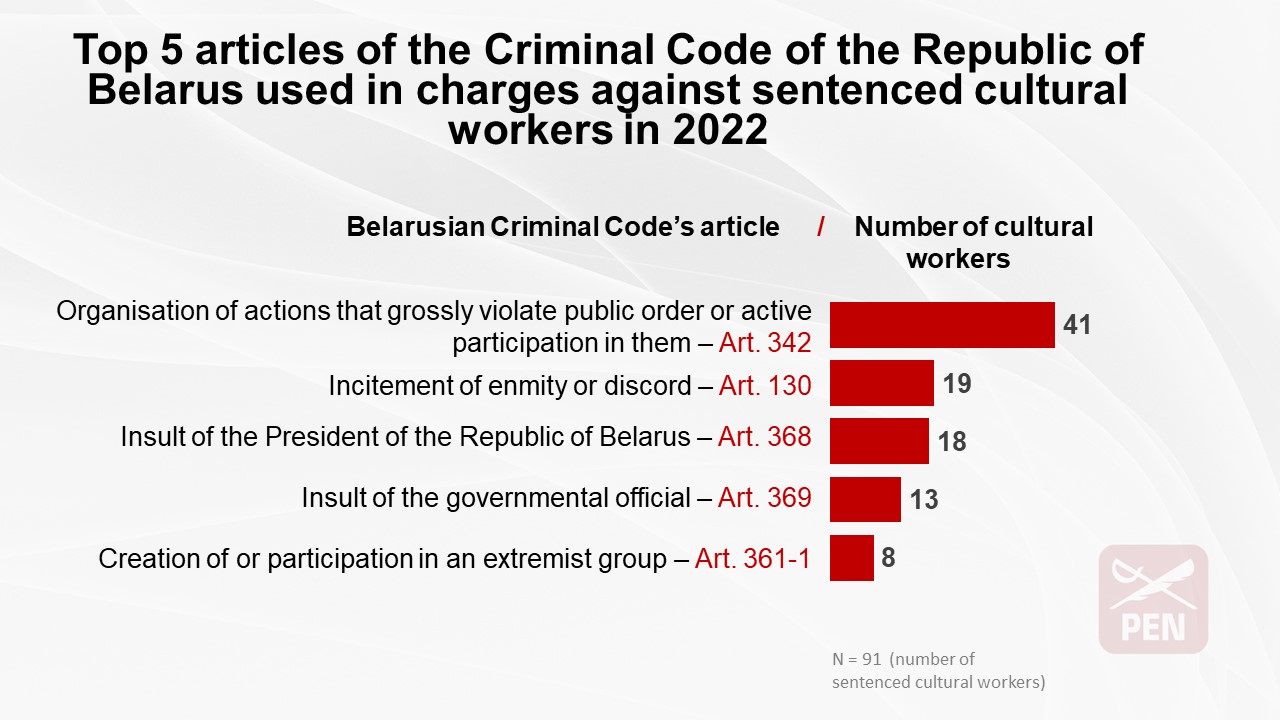

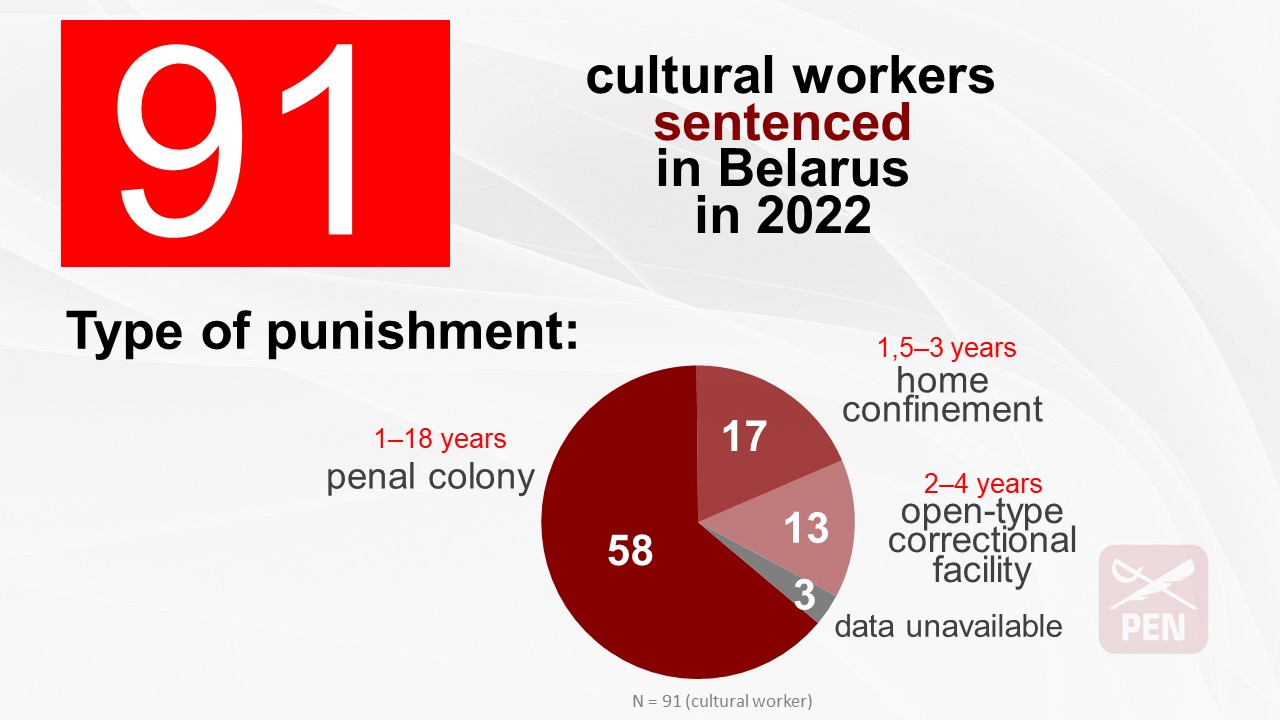

At least 91 cultural workers were convicted in 2022, three of them twice during the year: musicians Uladzislaŭ Pliuščau and Aliaksandr Kazakievič and poet, producer and blogger Uladzislaŭ Savin.

Regarding the number of articles in the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus applied, 59 cultural workers were charged under one, with Aliaksandr Franckievič charged under as many as 14 articles. Most frequently, charges were brought under Article 342 (“Organisation of actions that grossly violate public order or active participation in them”), which means criminal charges for participation in peaceful assemblies at the 2020 protests. At least 32 cultural workers were convicted solely under this article, and nine had these and other charges as part of their “crime.” The criminal prosecution under Articles 130 (“Incitement of enmity or discord”) and 368 (“Insult of the President of the Republic of Belarus”) take the second and third places in this ‘ranking’. The judicial system of Belarus uses them as a punishment for criticism of decisions and actions of representatives of the state and the country’s power structures. These articles were present in the charges against 19 and 18 culture workers, respectively, usually as part of the more extensive set of charges.

The imprisonment terms for convicted cultural workers ranged between 1 and 18 years, mostly in penal colonies. Twelve (12) were or will be sent to a strict-regime penal colony and 46 to a general-regime colony. Thirteen (13) cultural workers were sentenced to restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility, while seventeen (17) were sentenced to restricted freedom in a home confinement. We do not have any information on the court rulings for three (3) cultural workers who received sentences.

During 2022, the following convictions took place:

January: Kiryl Saleeŭ [17], sound engineer (3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility); Arciom Fiadosienka, music project author and print director (4 years in colony); Kim Samusienka, history re-enactor and activist (6.5 years in colony).

February: manager of cultural projects, author of a book of fairy tales written in captivity, businessman Aliaksandr Vasilievič [18] (3 years in colony); stage assembler Andrej Ščyhiel (2.5 years in an open-type correctional facility); cellist Illia Hančaryk (4 years in an open-type correctional facility); comedian Vasil Kraŭčuk (2 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); artist and interior designer Kanstancin Prusaŭ (3.5 years in colony).

March: history teacher Artur Eshvajeŭ [19] (3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility); author of a non-fiction book, journalist Alieh Hruzdzilovič [20] (1.5 years in colony); author of texts for Naša Historyja and Arche magazines Andrey Okushko (2.5 years in colony); Andrej Skurko, writer, musician and author of the magazine Naša Historyja (2.5 years in colony); street artist and IT specialist Dzmitry Padrez (7 years in a reinforced regime colony); non-fiction Internet author and blogger Paval Vinahradaŭ (5 years in colony); sound engineer Vadzim Dzianisienika (2.5 years in colony); amateur theatre actor Kanstancin Šulga [21] (3 years in an open-type correctional facility); director Dzmitry Pancialiejka [22] (1 year in colony); artist Aleś Puškin (5 years in a strict regime colony); poet, blogger and producer Uladzislaŭ Savin (8 years in a reinforced regime colony).

April: author and editor of “Wikipedia” Paval Piernikaŭ (2 years in colony); bass-guitarist Viktar Katoŭski (3 years in colony); former director of the museum “Pruzhanskі palacyk” Jury Zialievič (1,5 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); musician Vasil Jarmolienka [23] (3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility).

May: graphic designer Halina Siemiačka [24] (3 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); theatre performer Viera Cvikievič [25] (1 year in colony); former Russian language and literature teacher Anastasija Kucharava [26] (3 years of home confinement); jeweller and history re-enactor Michail Laban (4 years in colony); architect Ivan Paršyn (2 years in colony).

June: music college student Tacciana Barysovič [27] (3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility); cultural project manager and sociologist Tacciana Vadalažskaja (2.5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility); poet, translator and journalist Andrej Kuźniečyk (6 years in an enforced regime colony); former French teacher Iryna Jaŭmienienka [28] (3 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility); chief editor of the Belarus newspaper “Novy Chas” Aksana Kolb [29] (2,5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility); writer and activist Aliena Hnaŭk (3,5 years in colony); librarian and tour guide Iryna Koval (3 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); comedian, art director and TV presenter Aliaksandr Talmačoŭ (3 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); philosopher, methodologist and publicist Uladzimir Mackievič (5 years of reinforced regime colony); author, editor of Wikipedia and IT specialist Mark Biarnštejn (Bernstein) (3 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); writer Aliaksandr Novikaŭ (2 years in colony); musician and violin teacher Aksana Kaspiarovič [30] (1 year and two months in colony); designer Alina Kautunoŭskaja (sentence unknown).

July: Danuta Piarednia [31] (6.5 years in colony), a former student of Roman-Germanic philology at Mahilioŭ State University named after Kuliašoŭ; DJ Ihar Faliejčyk (2 years in colony); participant in folk art festivals Aliaksiej Viačerni (1 year and nine months in colony); writer and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava) (8 years and three months in a reinforced regime colony); journalist, author of prison literature and activist Dzmitry Daškievič (1.5 years in colony); local historian and traveller Ihar Haluška (2.5 years in colony); ceramist Anastasija Malašuk (3 years of home confinement); librarian Julija Čamlaj (2 years in colony); librarian Julija Laptanovič (5 years in colony); musician Aliaksandr Kazakievič (1.5 years of home confinement); architect Aliaksiej Parecki (3 years in colony); craftswoman and administrator of the Alfa-Business Hub space Alesia Kurejčyk (3 years of home confinement).

August: photographer Valieryj Klimienčanka (1.5 years in colony); musician Uladzislaŭ Pliuščaŭ (2 years in colony); photographer Aliaksandr Kudlovič (2 years in colony); creative director of the architectural bureau Kanstancin Vysočyn [32] (3 years of restricted freedom in an open correctional facility); commercial director of the Silver Screen cinema chain Aliaksandr Dziemidovič [33] (2.5 years of restricted freedom in an open-type correctional facility).

September: Viktar Kulinka, a digital artist (3 years in a reinforced regime colony); Aliaksandr Fiaduta, a writer, translator and literary scholar (10 years in a reinforced regime colony); Mikita Sliepianok, administrator of the cultural-historical Telegram channel Rezystans (3 years in a reinforced regime colony); author of prison literature, anarchist activist Aliaksandr Franckievič (17 years in a strict regime colony); artist Hanna Kisialiova (1.5 years in colony); designer Maryna Markievič (2.5 years in colony); musician Aliaksandr Kazakievič (2 years of home confinement); documentary filmmaker and journalist Ksienija Luckina (8 years in colony).

October: poet, journalist and media manager Andrej Aliaksandraŭ (14 years in colony); musician Siarhiej Daliviel (2 years in colony); local historian and activist Uladzimir Hundar (18 years in a reinforced regime colony); designer and photographer Dzianis Šaramieccieŭ (2 years in colony); Belarusian language and literature teacher Halina Tarnoŭskaya [34] (home confinement); concert organiser and activist Illia Mironaŭ [35] (1.5 years in colony); fiction writer and journalist Siarhiej Sacuk (8 years in colony); poet, producer and blogger Vladislav Savin (retrial, total – 10 years in a reinforced regime colony); history teacher and librarian Edhar Šyrko (3 years in colony).

November: ceramist Natallia Karniejeva (3 years of home confinement); musician and social activist Barys Kučynski (3 years of home confinement); local historian, tour guide and journalist Ihar Chmara (2.5 years of home confinement); Vadzim Vasiljeŭ, a lighting designer (12 years in a reinforced regime colony); Andrej Raptunovič, a teacher-artist (4 years in colony); musician Kryscina Čarankova (2.5 years in colony); architect and musician Aliaksandr Kucharenka (2 years in an open-type correctional facility); former teacher of Belarusian language and literature Emma Sciepulionak (2 years in colony); musician Siarhiej Nikiciuk (3 years in colony); re-enactor on Stalin’s Defense Line Vadzim Šylko (3 years in colony); musician Uladzislaŭ Pluščaŭ (repeated trial, total – 3 years in colony); former English teacher Iryna Abdukieryna (4 years in colony); English teacher Darja Cyrkun (3 years of home confinement); architects Tacciana and Ihar Kalesnik (sentences unknown).

December: musician and IT specialist Vadzim Hulievich (18 years in a reinforced regime colony); DJ and event host Kiryl Žaludok (1 year in colony); tour guide Oksana Mankievič (3 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement); historian Jaŭhieni Hurynaŭ (2.5 years of restriction of freedom under home confinement)

CONDITIONS OF DETENTION AND THE PRACTICE OF REPRESSION IN DETENTION FACILITIES

In 2022, we recorded 117 violations of the conditions of detention of cultural workers in detention facilities of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB. This is only a tiny fraction of what happens with political prisoners behind the walls of prisons.

Prisoners under administrative offences are placed in the following conditions in detention: total lack of sanitation, repeated overcrowding, cold, draught, lack of mattresses and bed linen, lights on around the clock, inedible food, homeless people “planted” in their cells to infest inmates with lice, night checks, refusal or poor quality of medical care, harsh and rude treatment by prison staff and other facts of pressure. We receive reports from detainees and criminal convicts about restrictions on walks, reading, exercise, refusal of calls and visits from relatives, denial of hospitalisation and parcels, and blocking correspondence. From 1 June 2022, authorities cancelled an additional “vitamin” package, which allowed prisoners to receive a specific set of fruit and vegetables weighing up to 10 kg once every 30 days. We collected evidence of problems with correspondence from dozens of imprisoned cultural workers. This is also confirmed by the termination of the project “Squared Letters” (Pisma v kletočku) [36], which cited the lack of feedback from political prisoners for more than six months as one of the reasons for this decision. Correspondence was significantly curtailed after Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine.

Prison administration routinely subjects inmates to various kinds of pressure, such as searches, provocation, overwork, miserable wages and difficult working conditions both in colonies and open-type correctional facilities. Nevertheless, penitentiary administrations apply additional methods of pressure: issuing reprimands for spurious reasons; placement on a preventive register of inmates “prone to extremism and other destructive actions” (entails extra work, checks, deprivation and control for such prisoners, their clothes and beds marked with yellow tags), which is the most common category for political prisoners; placement in a punitive isolation ward (SHIZO) or a punishment cell.

Political prisoners routinely end up in a cell-type facility (CTF) for “systematic” violations of the penal colony rules. CTF is a prison cell that can only be left for work or a half-hour daily walk, where parcels, letters, and shopping in the prison shop are restricted. During the analysed period, the following cultural workers were put (or remain) there: the author of prison literature and anarchist activist Mikalaj Dziadok (for four months), cameraman Viačaslaŭ Lamanosaŭ (term unknown), artist Aleś Puškin (for five months), UX/UI designer Dzmitry Kubaraŭ (six months), writer, bard and lawyer Maksim Znak (term in unknown), writer and activist Aliena Hnaŭk (two months).

Following the SHIZO and CTF punishment types are the transfer to the prison regime or initiation of a new criminal case under Article 411 of the Criminal Code (“persistent disobedience to the demands of the administration of a penal institution”). These two types of penalties became widely practised during the analysed period. According to the Human Rights Centre “Viasna”, in 2022, at least 41 political prisoners, including six (6) cultural workers, were transferred to the prison regime: artist and cartoonist Ivan Viarbicki (the term unknown), artist Aliaksandr Nurdzinaŭ (2 years), author of prison literature Mikalaj Dziadok (2 years and 10 months), cultural manager, video blogger and politician Siarhiej Cichanoŭski (3 years), author of prison literature Ihar Alinievič (the term unknown), history promoter and blogger Eduard Palčys (the term unknown) and artist Aleś Puškin (1.5 years). New criminal cases under Article 411 of the Criminal Code were initiated against 16 [by the end of 2022] political prisoners, including Ivan Viarbicki. [In January, it became known that Siarhiej Cichanoŭski and Aliena Hnaŭk faced similar charges]. In April 2022, poet Mikalaj Papieka saw his sentence replaced from restriction of freedom in an open-type correction facility to 8.5 months in prison.

PERSECUTION OF CULTURAL WORKERS FOR THEIR ANTI-WAR STANCE AND SUPPORT OF UKRAINE

On 24 February 2022, the Russian Federation launched military action against Ukraine. Belarus provided its territory to Russian forces for missile launches and the movement of military equipment. On 27-28 February, against the background of the referendum on amending the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus, rallies against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Belarus’ complicity in the war took place, resulting in the detention of at least 1000 people, according to the Human Rights Centre “Viasna”. In total, at least 2,000 people, including cultural workers, were detained during such protests in 2022.

In 2022, cultural workers were detained for anti-war statements and supporting Ukraine and its culture: for participating in anti-war rallies, praying for peace, publishing and making statements on social media, posting “fake” materials about the war, sending anti-war letters to state authorities, using official Ukrainian (blue and yellow) symbols and a combination of these two colours, writing in support of Ukraine, laying flowers at the monument to the Ukrainian classicist Taras Shevchenko and performing songs in the Ukrainian language.

In most cases, detained cultural workers were charged with such administrative offences as “unauthorized mass event” and “disobedience to police officers.” After their release, some would also experience dismissal from a state organisation, or an educational institution, deportation or a 10-year ban on entry into Belarus for foreign nationals (as was the case with theatre actor Maksim Shishko). Some administrative proceedings have since transformed into criminal cases, mainly under the “popular” Article 342, based on evidence of cultural workers’ participation in street protests back in 2020. Those examples include Wikipedia author and editor Mark Biarnštejn (Bernstein) (initially detained for editing articles on Wikipedia about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine), French language teacher Iryna Jaŭmienienka (detained on the referendum day), singer Meryem Herasimienka (detained for performing, among other things, the song “Obiymy” by Ukrainian band Okean Elzy).

Authorities initiated criminal prosecution against Danuta Piarednia, a student of Romance-Germanic philology at Kuliašoŭ Mahilioŭ State University with the record of excellent academic performance [expelled], who reposted an anti-war text calling to speak out against the war in Ukraine. She was convicted under Articles 368 (insulting the President of the Republic of Belarus) and 361 (calls to actions aimed at harming the national security of the Republic of Belarus) in the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus and sentenced to 6.5 years in prison. In June, Danuta Piarednia was placed on the list of “persons involved in terrorist activities.” A 20-year-old artist Andrej Raptunovič was sentenced to 4 years in prison under two articles of the Criminal Code, including Article 361-3 in the Criminal Code, for the attempt to join the regiment of Belarusians fighting for the independence of Ukraine. This article punishes for the participation in an armed formation or armed conflict, military actions, and recruitment or training of persons for such involvement on the territory of a foreign state.

PERSECUTION OF CULTURAL WORKERS WHO FLED THE COUNTRY

Persecution of disloyal cultural workers, who were forced to leave Belarus, took new forms in 2022. The previous practice of spreading insulting statements [defamation and discrediting in the state media], criminal prosecution, searches of the places of residence, destruction of apartments, arrest of property, pressure on relatives and international wanted listings evolved into introducing an ad-hoc procedure of trial in absentia. On 21 July 2022, Lukashenka signed the Law “On Amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code of the Republic of Belarus” [37] , which allows for the trial of Belarusians who are currently abroad, if they are accused of mass disorder, terrorism, and state treason. Thus, the case against Paval Latuška (Pavel Latushko), the former director of the Kupalaŭski Theatre (2019-2020) and Minister of Culture of the Republic of Belarus (2009-2012), will also be considered in these ad-hoc proceedings.

THE USE OF ANTI-EXTREMIST LEGISLATION TO SUPPRESS DISSENT

In 2022, authorities continued using anti-extremist legislation against opponents of the regime. Under the disguise of combating extremism and terrorism, they suppressed all forms of expression. Human rights organisations (Viasna, Human Constanta, BAJ, Sova) point to a new trend of the extremely broad interpretation of extremism legislation, which started after the August 2020 protests. The current law enforcement practice in Belarus treats as “extremism” participation in peaceful demonstrations, writing comments condemning violence on social media, or leaving emotional remarks about a representative of the authorities. On 5 January 2022, Lukashenka signed the Law on Amendments to the Law “On Citizenship of the Republic of Belarus” [38], which includes an option to deprive Belarusians of their citizenship for “extremist” activities.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA) of Belarus maintains three lists [39] : “List of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, foreign persons or stateless persons involved in extremist activities”, “List of organisations, individual entrepreneurs involved in extremist activities” (introduced without a court decision) and “The National List of Extremist Materials” (by court decision). All three lists are being constantly updated with new entries.

The first 140 names in the list of “citizens involved in extremist activities” were made public in March 2022. At the end of the year, this number was already 2,236, including at least 102 cultural workers.

The “list of organisations and self-employed individuals involved in extremist activities”, similar to the list of citizens mentioned above, was introduced in June 2021 after the amendment of the Law “On Countering Extremism”. It contains new initiatives which emerged in the wake of the 2020 protest movement and such long-established independent organisations as the BelaPAN news agency, Belsat satellite TV channel, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Belarusian service and others. 107 entities were on the list by the end of the year, including those 80 added during 2022. Of these, 10 “extremist organisations” belong to the field of culture: Belarusian Council for Culture, an initiative that supports and promotes Belarusian culture; the Internet portal Tut.by, which had the Playbill (Afisha) section dedicated to culture; Naša Niva, European Radio for Belarus (Euroradio) and Kyky.org, which have Culture sections on their websites; regional media outlets Flagštok (Homiel) and Hrodna.life (Hrodna), which, among others, covers culture and preservation of historical heritage; the Telegram channels about Belarusian history and culture Historyja and Rezystans; the VKontakte group “Let’s Make Belarusian the Only State Language!”

“The national list of extremist materials” is the oldest of the three, run since September 2008, after the adoption of the Law “On Countering Extremism” [2007]. It is difficult to calculate the total number of pieces of content in it, as the numbering is not maintained. Still, it is evident that since the second half of 2020, the list has been expanding nearly uncontrollably. During the last year alone, the National Commission on Assessment of Information Products for the Presence or Absence of Extremism reported that it had evaluated 1400 materials and established the existence of extremism and rehabilitation of Nazism features [40] in 1379 of them (98.5%), adding the corresponding titles to the list. Among those added to the list in 2022, we single out 56 items related to the field of culture or cultural workers (although upon closer examination, there could be many more). These include:

- 12 songs: 10 songs by the Tor Band, the song “Our Father is Bandera, Ukraine is Mother”, and the musical sketch “KhaiTak – Quietly On the White Wall of a City Council”.

- 10 books: Viktar Liachar, “The Military History of Belarus. Heroes. Symbols. Colours”; Anatol Taras, “Belarus at the Crossroads. Collection of articles”; Alhierd Bacharevič, “Dogs of Europe”; Zmicier Lukašuk, Maksim Harunoŭ, “Belarusian National Idea”; Kanstancin Zalesski, “Scientific and popular edition: “Heroes” Luftwaffe. First Personal Encyclopaedia”; Anatol Taras, “A Short Course of the History of Belarus in the IX-XXI Centuries”; Sviatlana Kazlova, manuscript “Agrarian Patriotism of the Nation in Western Belarus: Planning. Occupation. Azhytsovlenie (1941-1944)”; Joseph Brodsky, “The Tale of the Little Buksir” (translated by Aleś Alejnik); Uladzimir Arloŭ, Pavel Tatarniokaŭ, “Homeland: A Short History”. In 2 parts. Part 1 “From Rahnieda to Kosciuszko”; Otto Skorzeny, “The Unknown War”. [At the time of publication, the list has grown to 24 books].

- Media websites with content on cultural issues: Bielaruskaie Radio Racyja, Rehijanalnaja Hazieta, Viciebski Kurier, media-polesye.by, nadniemnemgrodno.pl, MOST, Polskieradio.pl, Polskieradio24.pl, The Village Belarus, Carkva newspaper and others.

- Other materials: the websites of shops selling national symbols Symbal.by and Roskvit, the website and social media accounts of the Belarusian Council of Culture, YouTube channel, Patreon and social networks of Tor Band, the clip “Flowers and Bullets” and YouTube channel of Deadfall, YouTube channels “Life is Raspberry” (Zhizn-Malina), “Ms. Anne Nittelnacht” (a Jewish cultural research project), and several others.

“The list of organisations and individuals involved in terrorist activities” [41] is maintained by the Committee for State Security (KGB). Since the autumn of 2020, the list includes not only names of internationally recognised terrorists but also Belarusian public figures and activists, including representatives of the cultural field. In 2022, the list included 14 cultural workers: Siarhiej Sparyš, Maksim Znak, Maryja Kaliesnikava, Danuta Piardenia, Aksana Kaspiarovič, Aliaksiej Parecki, Ivan Viarbicki, Julija Chamlaj, Paval Vinahradaŭ, Siarhiej Cichaŭnoski, Viktar Katoŭski, Ivan Paršyn, Andrej Pačobut and Ihar Haluška. Ihar Alinievič, Paval Latuška, Anton Matolka (Motolko) and Vadzim Hilievič featured in the list as far back as late 2021. In total, at least 18 people associated with the field of culture were declared “terrorists” in Belarus.

13 cultural workers remain on both lists – “extremist” and “terrorist” – due to the similarity of the selection criteria, human rights defenders point out.

As Paval Sapielka, a lawyer with the Human Rights Centre “Viasna”, notes, people on such lists suffer a significant “loss of rights” during the term of conviction and beyond. The lists also affect the ability to engage in certain activities (in particular, publishing and teaching), create difficulties in carrying out financial transactions (blocking bank accounts), and others.

***

In November 2022, authorities added the greeting “Žyvie Belarus!” (Long Live Belarus!) and the response “Žyvie!” to the “list of Nazi symbols and paraphernalia” [42]. The slogan “Žyvie Belarus!” is called by propaganda media “collaborationist greeting” [43] . However, it is not clear from the document whether it is considered “Nazi” to pronounce this slogan without sign accompaniment.

PRESSURE ON CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN THE CULTURAL SECTOR

There were 217 violations concerning cultural organisations recorded in 2022. Almost half of those cases have to do with the activities of non-governmental organisations. The most widespread violations against the rights of civil society organisations and initiatives in Belarus in the last two years are the creation of administrative obstacles to carrying out activities, violation of the right to freedom of association, and censorship.

- Forced liquidation

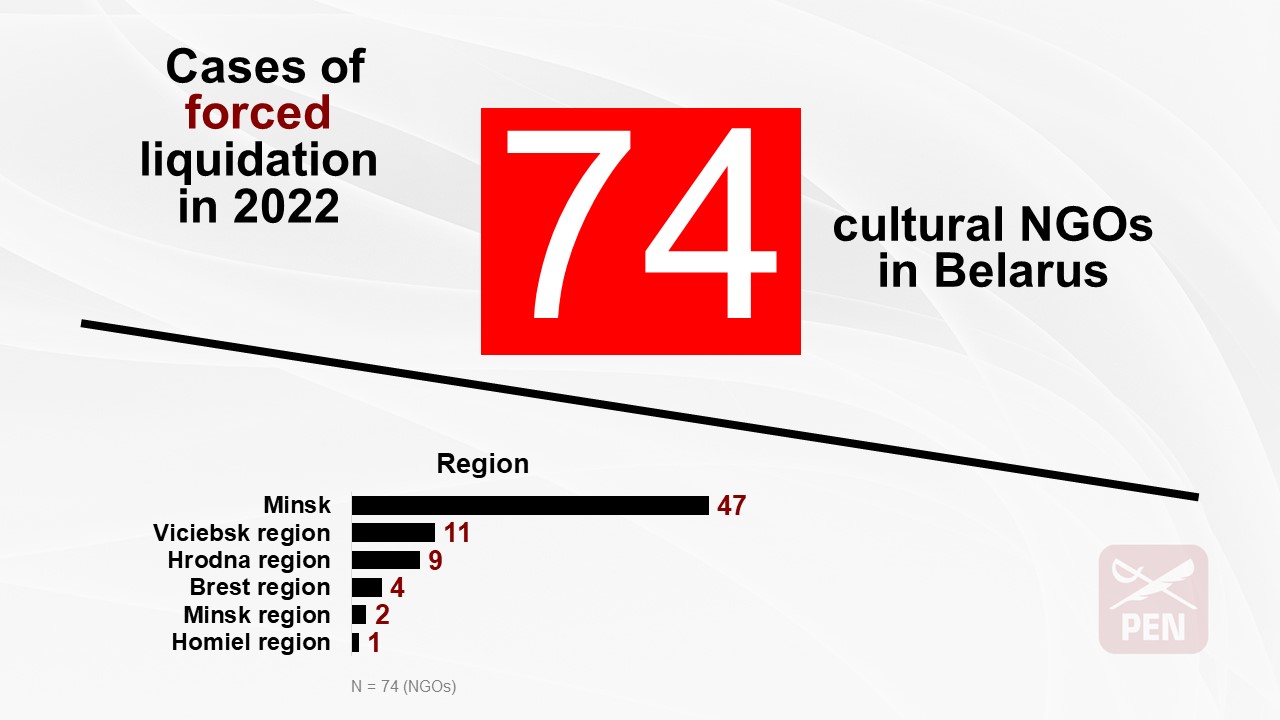

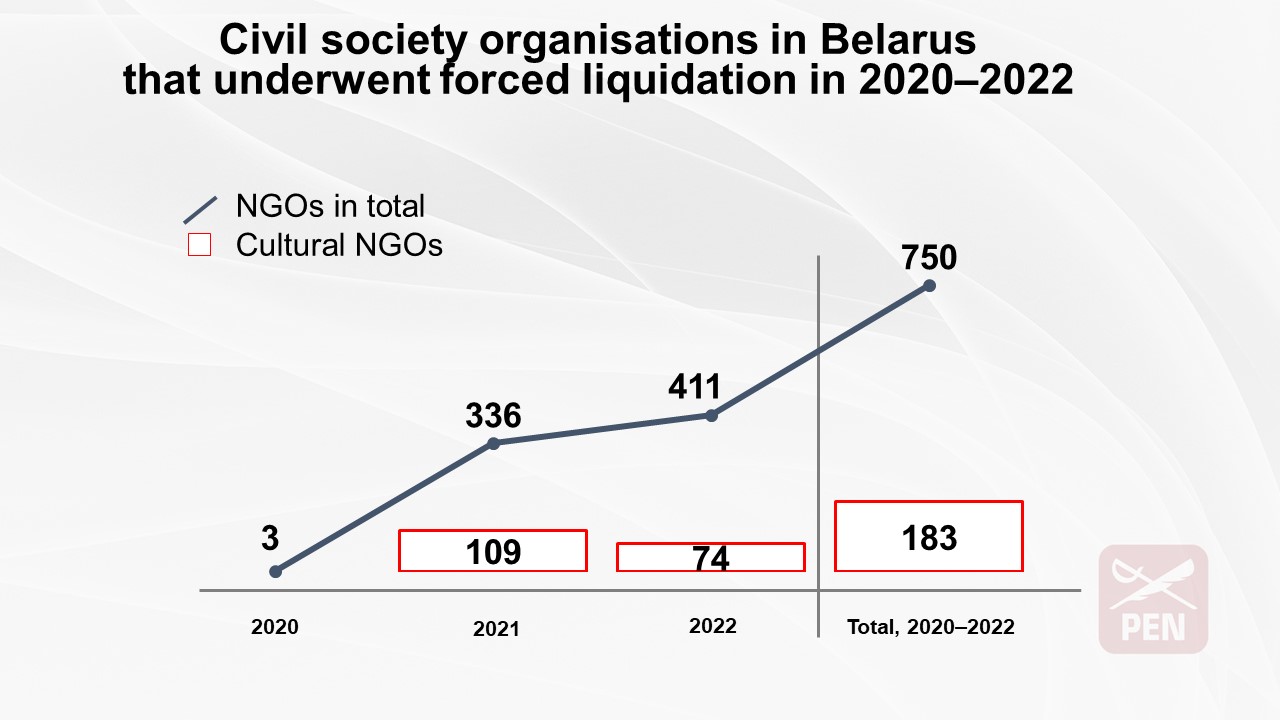

Since January 2021, Lawtrend and the OECD monitor the involuntary liquidation of NGOs [44] . In 2022, 411 NGOs were forcibly dissolved, including 74 organisations of cultural nature that focused on writing, theatre, history, dance, and others. 25 of them were the oldest organisations established back in the 1990s. Those are non-profit organisation such as “Polish folk Traditions Club” (1994), “The Polish Culture Society in Lidčyna” (1994), “Polska Macierz Szkolna” (1996) in the Hrodna region; “Polack Jewish Cultural Centre” (1992), “Viciebsk Musical Society” (1994) in the Viciebsk region; “Belarusian Association of Architecture Students” (1994), “Belarusian Association of Historians” (1994), “Belarusian Association of Piano Teachers” (1996), “Belarusian Association of Germans “German House” (1997), “Padarožnaya Družyna Bielarusaŭ “Kaliadniki” (1999) in the Minsk region, and others.

According to the results of the two-year monitoring, the list contains information on 750 NGOs [45] , 183 of which are cultural organisations.

In parallel to forced liquidation, the self-liquidation of non-profit organisations took place in 2022. The monitoring does not keep records of the self-liquidation of NGOs; however, it is crucial to understand that most of those instances were forced decisions by the founders of organisations due to the unfavourable socio-political situation in the country and often due to pressure from the authorities. By late 2022, Lawtrend [46] listed 417 civil society organisations that self-liquidated during the same year, including 34 that we regard as representing the field of culture. Most of those organisations were in the Brest region (15 out of 34) and in Minsk (8). All in all, in 2021–2022 forced liquidation and self-liquidation were behind the loss of 1167 non-governmental organisations. At least 280 of them were from the cultural sector.

- Criminal liability for organising and participation in the activities of an unregistered organisation

In January 2022, the Law of the Republic of Belarus No. 144-Z “On Amendment of the Codes” came into force, reintroducing Article 1931 in the Criminal Code of Belarus (abolished in 2019), which established responsibility for the Illegal organisation or participation in the activities of a public association. Organising and participating in the activities of an organisation without the registration is again punishable by up to two years in prison. According to reports, the prosecutor’s office of the Hrodna region initiated a criminal case against the management of Klerygata Ltd over the illegal organisation of the association and participation in it [47]. This company served as the foundation for the operation of the Union of Poles in Belarus

- Reducing the list of NGOs eligible for office rental privileges

The practice of depriving organisations of the benefits continued. On 30 March 2022, the 27 December 2021 Council of Ministers’ Resolution came into force, significantly reducing the list of NGOs entitled to a 90 per cent discount for the rental of premises. The new list does not include 80 public associations and foundations from the previous one. Respectively, 78 of those organisations experienced a ten-fold increase in office rental fees since April 2022 [2 were self-liquidated in December 2021]. This number includes 15 public associations and organisations with cultural component in their activities: the Belarusian Union of Architects, the Belarusian Union of Masters of Folk Art, the Belarusian Union of Musicians, the Belarusian Union of Theatre Workers, the International Public Association “Mutual Understanding”, several associations of Jews and others. Most of these organisations have operated in Belarus for more than 25 years. At the same time, the list of NGOs eligible for an exemption now includes the pro-governmental association Patriots of Belarus, registered in late 2020.

In the last two years, authorities reduced the number of non-profit organisations who could receive support in renting premises from 195 to 23. By the time of the adoption of this regulation in 2010, nearly 500 of them were receiving such benefit. All public associations were entitled to this benefit [48] before the introduction of this list.

- Imposing sanctions on public associations

In October 2022, we noticed a new trend of sanctions against NGOs: suspension of their activities [49]. There have been at least seven such cases, including three that classify as cultural: Organisation of Friendship of Iranians, the “Dance and Sports League”, and the “Lyudmila Dance and Sports Club” children’s public association.

***

Apart from the above, non-governmental cultural sector faced increased attention from the Ministry of Justice, resulting in refusals to approve money transfers and register funding with the Department for Humanitarian Affairs, “recommendations” from security bodies not to hold certain events and unexpected termination of premises rental contracts.

It is also worth noting the situation when domain names previously owned by blocked organisations use. For example, pen-centre.by, the domain PEN Belarus, was initially blocked and eventually liquidated in August 2021. Currently it hosts a PEN tourist service, looking more like a fraudulent site, and this is not an isolated case.

CENSORSHIP AND ADMINISTRATIVE OBSTACLES IN THE CULTURAL SECTOR

This monitoring of violations is based on the facts that came to the attention of the monitoring team. It does not constitute an exhaustive analysis of the state of the sector but reflects the significant losses in every creative field.

The term ‘bookocide’ [50] suggested by philosopher Pavel Barkoŭski is the best description of the current situation with the national book publishing sector in Belarus. For the second year in a row, the independent book publishing sector is under repression. The well-planned and consistent process of its destruction includes pressure on and discreditation of Belarusian publishers, distributors, authors, and sometimes even readers. Some highlights as of late 2022:

- Publishing houses Limaryjus and Halijafy were liquidated; Medysont and Knihazbor had their licences suspended; the publishing house Januškievič was stripped of its licence at the beginning of 2023.

- The distribution of books already published by independent publishers and Belarusian books, in general, is hampered.

- Books not loyal to the regime and not in line with state ideology are withdrawn from bookshops and libraries.

- Books published in the Belarusian language are under the scrutiny of state control bodies.

- A dozen fiction and history books were added to the “extremist” materials list.

- Dismissals take place in the field.

On 22 March 2022, the landlord requested the Januškievič publishing house to vacate the office premises within three days “due to an urgent need”. On 16 May, the publishing house launched a new bookstore, “Knihaŭka”. On the same day, pro-governmental propagandists came and complained about the presence of allegedly “extremist and Nazi literature”. Later in the evening, the police searched the bookstore and ordered deputy director Siarhiej Makarevič to close the shop. The publishing house director Andrej Januškievič and the bookstore employee Nasta Karnackaja were detained and spent 28 and 23 days behind bars, respectively. The next day after the search, it became known that the police had confiscated 200 books and sent 15 for the so-called expertise to determine whether they contained any extremist elements. On the day of the shop’s opening and several days after the raid, propagandists released a series of defamatory materials about the publishing house, its employees, and the bookstore [51] . The bookstore closed after only 7.5 hours of work. Andrej Januškievič had to flee Belarus. Siarhiej Makarevič was detained on 4 November and currently remains in detention. [On 10 January 2023, the publishing house Januškievič was stripped of its licence and the right to publish books in the Republic of Belarus.]

In spring 2022, the Ministry of Information suspended for three months the operation of four independent publishing houses that published books by Belarusian authors or in the Belarusian language: Medysont and Halijafy on 15 April, Limaryjus and Knihazbor on 16 May. When the three-month suspension was over, the publishers’ attempts to get re-certified by the Ministry of Justice were unsuccessful. In late December 2022, the activity of Knihazbor was suspended by the Ministry of Information for another month [on 26 January 2023, the publisher announced the impending liquidation]. The publishing house Halijafy is in liquidation, and Limaryjus was liquidated.

At least 11 publishing houses/publishers have fully or partially relocated their operations abroad.

Publishers in Belarus are banned not only from publishing but also from selling previously issued books. In October 2022, Belkniha, the largest chain of state-owned bookstores across Belarus which already had removed the books of selected authors from its shelves in 2021, terminated contracts with publishers Januškievič, Knihazbor and Halijafy.

The blacklists of authors and publishers whose books are not allowed in libraries circulate throughout library networks. Libraries must remove those books from their collections.

Pro-government propagandists and “passionate citizens” visit bookstores with the purpose of “purging cultural visits“, searching for ideologically “harmful” materials on the shelves, namely: books with national (white-red-white) symbols, books authored by independent historians or writers disloyal to the regime, LGBT-themed books. “Myths about Belarus” by Vadzim Dzieružynski, “Welcome to Belarus” by Aleś Hutoŭski, “Summer in a Pioneer Tie” by Elena Malisova and Katerina Silvanova (about the relationship between two young men) and other books on LGBT topics were withdrawn from sale or put into storage in selected shops. Regime loyalists publicly support such “purges” at bookshops [52].

The practice of discrediting independent publishers, “undesirable” authors and books continues in state media and pro-government Telegram channels.

Ten books, including eight by Belarusian authors, were recognised as extremist materials during the year. Now the distribution of these books is criminally punishable, and the prosecutor’s office periodically monitors bookstores and websites for sales of books from the National List of Extremist Materials, issuing instructions to remove them from the shelves. “We are lucky not to see them on bookshelves today. […] The failure to understand that books are much more powerful weapons than missiles and tanks leads to the situation when people have to use missiles and tanks,” Deputy Information Minister Ihar Buzoŭski said when speaking about political journalism during a round table of the pro-governmental Union of Writers of Belarus [53]. Nobel Prize literature laureate Sviatlana Alieksijevič’s (Svetlana Alexievich) books are also under evaluation by the special national committee on extremism.

The periodicals on Belarusian culture are losing highly qualified specialists. The so-called “optimisation” is in progress at Mastactva (Arts), one of the oldest art magazines, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in January 2023, resulting in firings of its staffers. Writer and ballet critic Tacciana Mušynskaja, who had worked with the magazine as the music desk editor since 1991, editor of the contemporary arts desk Alesia Bieliaviec, typesetter Aksana Kartašova, and at least three more writers lost jobs by “mutual agreement of the parties” in 2022. Dismissals from the newspaper Kultura (“Culture”) are known [54]. Last year, three literary magazines, Polymia, Maladość and Nioman, had their chief editors replaced and several specialists fired. As one of the former employees pointed out, “only the proven and obedient ones keep their jobs.”

At the end of February, Aliaksandr Lukašaniec, an academic linguist who denounced violence after the 2020 election, was dismissed from Jakub Kolas Institute of Linguistics. The administration did not renew his contract. In November, the deputy head of research, Siarhiej Haranin, was dismissed. On 1 July, Aliaksandr Hruša, a medievalist historian and director of the Central Scientific Library at the National Academy of Sciences, was fired.

In 2022, the pressure on politically “undesirable” painters continued.

- In March 2022, painter Aleś Puškin was sentenced to five years in a strict regime colony for displaying a portrait of an anti-Soviet underground member Jaŭhien Žyhar at the Center of Urban Life in Hrodna in 2021.

- The Ministry of Culture pressures authors disloyal to the regime, adding their names to so-called “blacklists”, denying them solo and group exhibitions in state-owned exhibition centres, selling works to museums, etc.

- Pro-government activists use complaints and denunciations to force the removal of individual works from exhibitions or shut down entire pavilions.

- Censorship became a pre-condition of life and creativity.

- Artists’ self-censorship is a way of survival and a conditioned reflex.

Authorities ordered an expert examination of the art object titled “Till Death Divides Us” by Hanna Silivončyk after allegations of pornography at the exhibition “Troubled Suitcase” (10.12.2021 – 10.01.2022) in the gallery of the non-governmental Union of Designers. As a result, proceedings were initiated not only against the exhibition but also against the NGO that hosted it.

In late March, Ryhor Ivanaŭ’s exhibition “Hour of Screens” was dismantled at the Palace of Arts in central Minsk a week before the official end date. Simultaneously, Siarhiej Hrynievič’s exhibition “Demography” was closed prematurely “for technical reasons.” The latter case is remarkable because the collection did not display seven works that did not pass censorship.

The easel sculpture exhibition “SCULPTURE” opened at the gallery “400 squares” in Hrodna on 29 April but lasted only four hours. Local ideologues insisted on removing specific authors and works from the exhibition. Still, the project curator Ivan Artymovič and gallery owners believed “the reasons were far-fetched” and did not agree to comply. The display, with the works of 17 sculptors on display, was closed immediately after the opening. The gallery closed shortly after failing to renew the rental agreement.

On 12 May, Art-Minsk’s annual art exhibition opened at the Minsk Palace of Arts, initially announcing 550 works by 240 contemporary Belarusian authors. However, Ministry of Culture censors removed the works of several dozen artists. The monitoring of PEN Belarus contains information about 19 artists who lost their exhibition space, but an unconfirmed report suggests that there more than 40 censored artists.

On 28 June, the Factory space in Minsk hosted “the fastest exhibition of my life”, as described by one of the three project participants Iryna Malukalava. “This is a diagnosis“, an art exhibition about criticism in art, lasted only a few hours.

On 10 November, the Decart-22 Triennial of Decorative Art, an exhibition of works in ceramics, glass, and textiles, opened at the Palace of Arts in Minsk. One day later, authorities sent the list of politically unreliable artists whose works the organisers had to remove from the display. The circular listed at least a third of the authors. As of writing, it is unclear how this requirement affected the show’s work.

Photographers also face censorship. For instance, Sviatlana Niesciarenka’s exhibition “Hrodna sunsets” was cancelled in the “Fiestyvalny” cultural centre. Similar things happened to other photographers.

We have information about other cases of interference and control over art and photographic exhibitions and subsequent conversations with their organisers by local and national administrations. Authorities continue questioning designers and photographers who cooperated with the NGOs and unions currently persecuted. In Minsk, local authorities ordered to paint over several murals. In Hrodna, artists were suddenly ordered to pay 22,000 BYN (about 8,000 EUR) to the state – the fees for using their studios over the past six years.

- Layoffs in theatres all over Belarus

- Control and censorship in repertory

- Taking down performances as a way of self-preservation

- Russification of the Belarusian theatre

In 2022, theatres in Belarus continued to lose highly professional specialists. We know the names of 19 cultural sector representatives who either had their contracts not renewed or were dismissed “by mutual agreement of the parties”. Information about fourteen (14) of them is known from public sources. On 20 January, Uladzimir Savicki was fired from the Theatre of Young Spectators in Minsk after 12 years in service. On 15 March, director Andrej Saŭčanka was no longer leading the student theatre “On the Balcony” at the Belarusian State University “by mutual agreement of the parties”.

In March-April, actors Maryna Zdaronkava, Maksim Šyško, Aliena Bojarava and Maryja Piatrovič were fired from the National Theatre of Belarusian Drama. On 1 April, Ivan Kasciachin was no longer a conductor at the National Opera and Ballet Theatre. Aleh Liasun stopped working as a conductor in late December. Independent media reported that dismissing “several dozen of people” from the theatre was imminent over their civic position. We know the names of five (5) employees. On 26 April, director Michail Krasnabajeŭ, who joined the theatre in 1985, was fired (contract not renewed) from Viciebsk’s Jakub Kolas National Theatre. On 13 March, V. Dunin-Marcinkievič Regional Theatre of Drama and Comedy in Mahilioŭ did not renew the contract of actor Vadzim Babinič. In 2022, he also stopped being the head of the troupe of the National Theatre at the Babrujsk Palace of Arts. On 31 August, actress Alla Hrachava who had worked in the Babrujsk theatre for more than 40 years, had her contract terminated. Jaŭhien Klimakoŭ, who has been the director of the Belarusian State Puppet Theatre since 1985, is not performing this role anymore. Siarhiej Čyhryn, the head of the literary department, was fired from Slonim Drama Theatre. At the end of December, Homiel City Youth Theatre terminated a job contract with director Alena Mastavienka.

More censorship highlights: The Ministry of Culture blocked the play “A Test Essay” at the Theatre of Young Spectators. The plot features a conflict between the justice-seeking graduates and the school administration. In September, the Minsk city executive committee’s officials did not authorise Music Theatre’s operetta “The Duchess from Chicago“, which draws parallels with the contemporary reality and contains jokes about the outbreak of the war, among other things. Its premiere, scheduled for 23 and 24 September, was cancelled. The performance did take place on 11 November in a slightly abridged and censored version. At the end of December, after an appeal of the pro-governmental activist Volha Bondarava about the incompatibility of the performance “Monsters on New Year Holidays” by the KAKTUSS Theatre Workshop with the “spiritual and moral education of children and youth”, a special committee of the Ministry of Culture banned the following shows of the play.

On 12 July, the cultural institution Theatre-Territory of Musicals was forcibly liquidated. At the beginning of the same year, the theatre twice failed to receive permission to show the play “Figaro” at the Palace of Trade Unions in Minsk. In addition, by the beginning of the new season in the autumn of 2022, several theatres were forced to remove selected plays from their repertoires.

De-Belarusianisation takes place in the theatrical field, as well. The new Theatre of Young Spectators director and an actress loyal to the Lukashenka regime, Viera Paliakova, announced that the theatre would give up staging plays exclusively in Belarusian, which had previously made the theatre stand out among other professional teams. Only 6 out of 28 Belarusian theatres worked solely in the Belarusian language. In June, the theatre held a Russian-language premiere of the play based on the story “Alpine Ballad” by Belarusian literature classicist Vasil Bykaŭ. It means that there is one less Belarusian-language theatre in the country. When asked about the situation with the Belarusian language in the theatre in Babrujsk, actress Alla Hrachava spoke about young actors who had refused to perform plays in the Belarusian language, citing their Russian origin [55].

- Dismissals from state cultural institutions

- Criminal prosecution for professional activities

- Administrative obstacles to concerts

- Reducing the number of performance venues

In 2022, deputy director general Andrej Lapcionak, symphony orchestra harpist Alena Maksimava, and several other specialists were dismissed from the Belarusian State Academic Symphony Orchestra. The National Gymnasium-College of the Academy of Music sacked more than 20 teachers. The names of three are publicly known: Uladzimir Perlin, honoured artist of the Republic of Belarus and head of the concert orchestra of the Academy; Alla Mazurava, art director of the children’s choir Singing Musicians, and Siarhiej Tumarkin, concertmaster of the oboe band of the BGAM.

Irdorath band leaders Nadzieja and Uladzimir Kalač, convicted for “repeatedly leading a column of protesters … using musical instruments” [56] in August 2020, continue to serve a two-year prison sentence for their musical activities. Singer Meryem Hierasimienka was detained in early August, the day after the street concert near Banki-Butylki bar, where she performed a song by Ukrainian band Okean Elzy. After almost half a year in pre-trial detention, the singer was put under home confinement for 3 years. At the end of August, the YouTube channel, Patreon, social media accounts and music compositions owned by Tor Band, a music band that had originated in Rahačoŭ during the 2020 presidential election, were designated “extremist materials”. Two months later, the members’ detention followed – musicians Dzmitry Halavač, Jaŭhien Burlo and Andrej Jaremčyk were sentenced to 15 days of administrative arrest several times in a row. Tor Band’s YouTube channel was deleted with all the videos that had over 5 million views. On 16 January 2023, authorities declared the music band “an extremist formation” and brought criminal charges against all three musicians. The detention in mid-October of brothers Uladzimir and Dzmitry Karakin, musicians of Litesound band, is also noteworthy. Even though they were detained for participating in post-election protests, there are grounds to believe that their persecution was, among other things, revenge by the government agencies for the “ingratitude” and political infidelity of the band, which represented Belarus at the 2012 Eurovision Song Contest. Human rights defenders recognised them as political prisoners.

In 2022, there were cases when street musicians were detained and had their equipment and instruments confiscated. There are known instances when state security agents were present during concerts of state-run bands. The Ministry of Culture refused to issue touring licenses to the Shortparis group, whose frontman Mikalaj Kamiahin is known for his anti-war stance, and some other Russian bands. At the end of December, authorities cancelled the concert of Homiel folk band Ban Žvirba for “reasons beyond the band’s control”. Other non-public cases of bans on musicians’ participation in concerts and festivals are also known.

Administrative obstacles, censorship, and persecution in general deprive musicians of the opportunity to rehearse and tour. Some groups suspend their work indefinitely, the few concert venues in the country cease to exist. The Minsk music club Brugge has “suspended” operation since mid-May. Another Minsk bar Banki-Butylki remains closed “for technical reasons,” its director Andrej Žuk in police custody for more than six months after the performance and consecutive detention of Meryem Herasimienka. On 16 September, the music bar Graffiti, in operation since 1999, was shut down in Minsk. In late December, Minsk rave club HIDE announced its closure following the raid by riot police on a night party on 5 November.

- The abject nature of Belarusian state cinematography

- Censorship of feature films

- Criminal prosecution of a filmmaker for a documentary

This monitoring report includes just a few episodes associated with violations in the field of Belarusian cinematography. Most data from public sources mainly concerns state regulation and ideologisation of the national film studio Belarusfilm. The collected cases included such ideology-focused events as film screenings, meetings with directors and actors, film lectures for children jointly with GONGO Belaja Ruś activists, the state order for producing “legit” films about the war and the right heroes, promotion of Belarus-Russia cooperation, and others. Independent media reports suggested massive layoffs at the film studio. However, we do not have supporting evidence. We also possess information that Belarusfilm must obtain clearance from the Ministry of Culture and the chief ideologist at the National Film Studio for all actors participating in the film projects.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the consecutive departure of major American film distribution companies from Russia and Belarus, the repertoires of Belarusian cinemas shrank to mostly Russian and Soviet-made films, cartoons and films with military themes. In late autumn, cinemas began ‘screening’ pirated content. On 3 January 2023, a new law officially endorsed parallel import, or the import of intellectual property without the consent of the rights holders [57].

Censorship continued. After the official launch of Uladzimir Kazloŭ’s “Three Comrades” failed to take place, the film director released the film on his YouTube channel [58]. In October, the Investigative Committee opened a criminal case against Volha Švied following the release of her movie “Kalinoŭski”, a biopic about Kastuś Kalinoŭski, the leader of the 1863-1864 anti-Russian uprising and antagonist in state propaganda. Historian Vasil Hierasimčyk, the documentary’s main character, had to flee Belarus due to persecution by law-enforcement bodies. In November, the authorities banned the screening of Andrej Kudzinienka’s (Kudinenko) feature film “Ten Lives of a Bear”, initially scheduled for distribution at the Listapad film festival and in several cinemas in Minsk. The film disappeared from the posters. The movie “This is me, Minsk” the rights belonging to Belarusfilm, was removed from the program of Polish Film Festival of Belarusian cinema. Under the agreement, screenings abroad are only allowed after the premiere in Belarus, where it cannot take place for unknown reasons. The Listapad organisers declined to show the film at the festival.

- Dismissals from state cultural institutions

- Interference in tourism and harassment of tour guides

Politically motivated dismissals also continued in the museum sector. In October, the director of the Belarusian State Archives and Museum of Literature and Art, Hanna Zapartyka, who joined the museum in 1978 and had been its director since 1994, saw her job contract not renewed. In December, authorities dismissed the Museum of the History of Belarusian Cinema director and film critic Ihar Aŭdziejeŭ not long before his 20th anniversary at the post.

In December, we learned about mass dismissals at the National Art Museum. The monitoring team has the names of eight people fired on 23 December alone. Independent media reported about 18 sacked employees. Those are not the first or only dismissals from that museum since 2020. We also have information about similar cases in the state Maksim Bahdanovič Literary Museum, Janka Kupala Museum in Minsk, and others. Although there are only 13 officially known cases of dismissals in the sector, the number does not reflect the actual scale of what is happening. For instance, there were confidential reports about “quiet” layoffs in the National Historical Museum, but this information was never made public.

In November, Anatol Biely’s private museum in Staryja Darohi, Minsk region, grabbed the attention of pro-governmental activist Volha Bondarava. The museum’s outdoor exhibition displayed the busts of several Belarusian political and cultural figures, such as poets Natallia Arsienjeva and Larysa Hieniuš, revolutionary Kastuś Kalinoŭski and other personalities. After she described the exhibition as “Russophobic and pro-Nazi,” [59] authorities ordered the removal of all the busts and bas-reliefs.

In 2022, authorities also took on the tourism sector, particularly tour guides. A series of detentions occurred in August and September, while pro-government media published articles defaming some travel agencies and persons working as guides. Under the potential threat of persecution for free expression, the guides had to self-censor and pick what they could and should speak about. Under the 2 September 2022 Resolution No. 582 “On Tour Guide Services” [60], tour guides and guide-interpreters must be certified to prove their qualifications. The certificate, issued for five years, can be suspended if there are complaints about the quality of service. Another resolution came into force on 7 December [61], stipulating that persons convicted under “protest articles” (130, 342, 367-368 and others) are not eligible for certificates. Beginning from 1 January 2023, only approved specialists can work as tour guides.

OTHER CULTURAL SPACES