Since October 2019, PEN Belarus has systematically collected information on violations of cultural rights and human rights in the case of culture workers. This document contains statistics and analysis of these violations from the first quarter of 2022. The material was prepared according to general information collected from open sources and through direct communication with cultural figures during this period.

GENERAL RESULTS

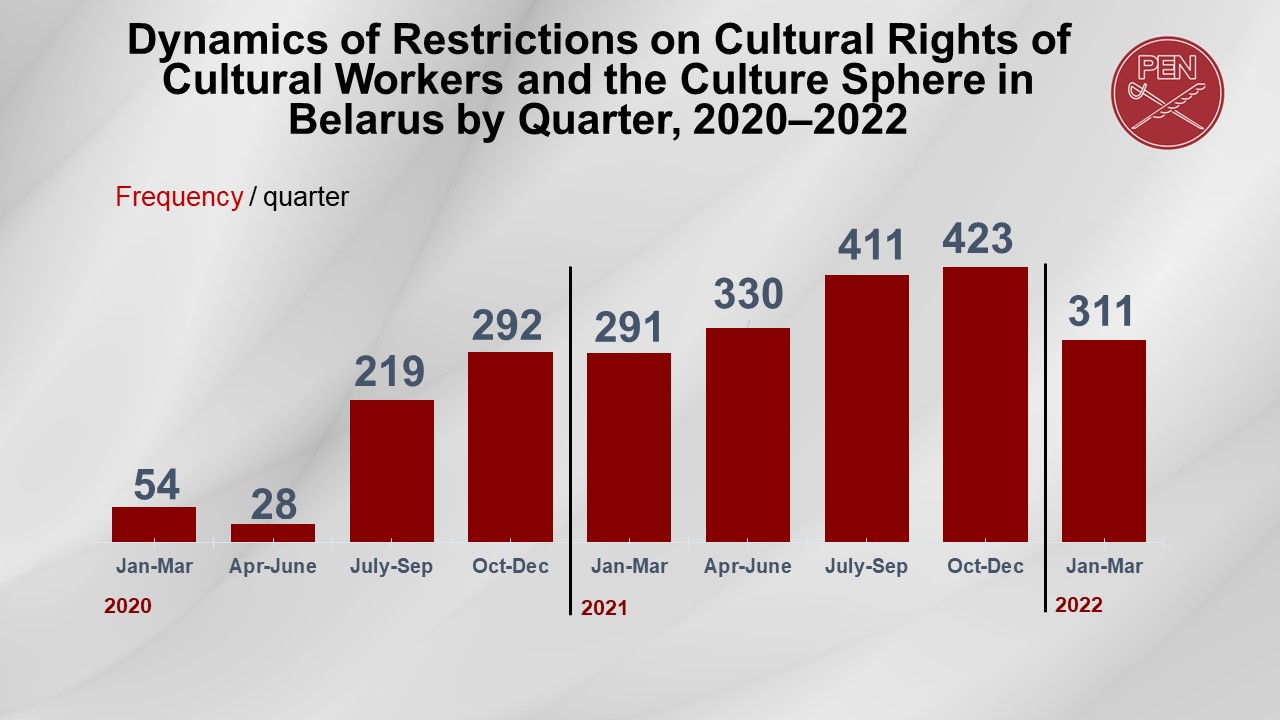

From January – March 2022, there were 311 instances of rights violations. The number of cases collected is comparable to the same period in 2021 (291 cases). Despite the apparent decrease in repression over the second half of 2021, there is more to the conclusion than that: case quantities were previously impacted by a governmental campaign to liquidate NGOs, and by the first quarter of 2022, this was already less impactful on the number of violations. The degree of repression against culture workers has been at a consistent frequency.

POLITICAL PRISONERS – CULTURE WORKERS

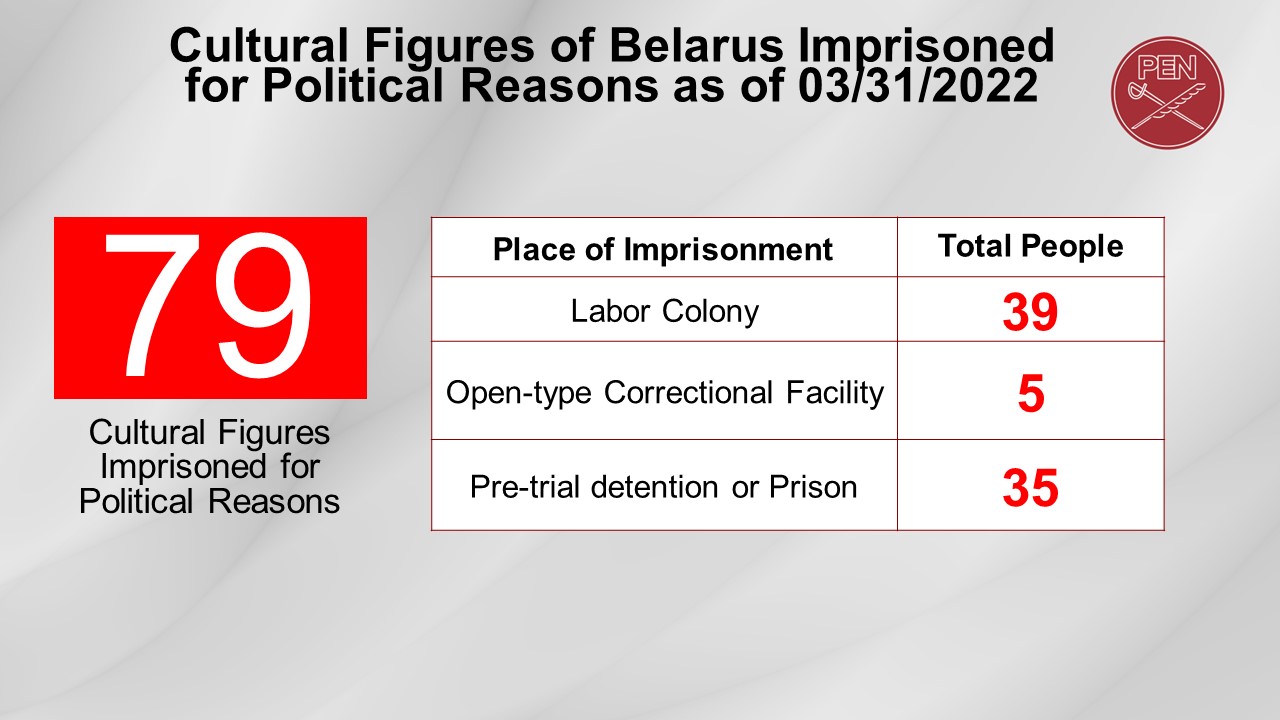

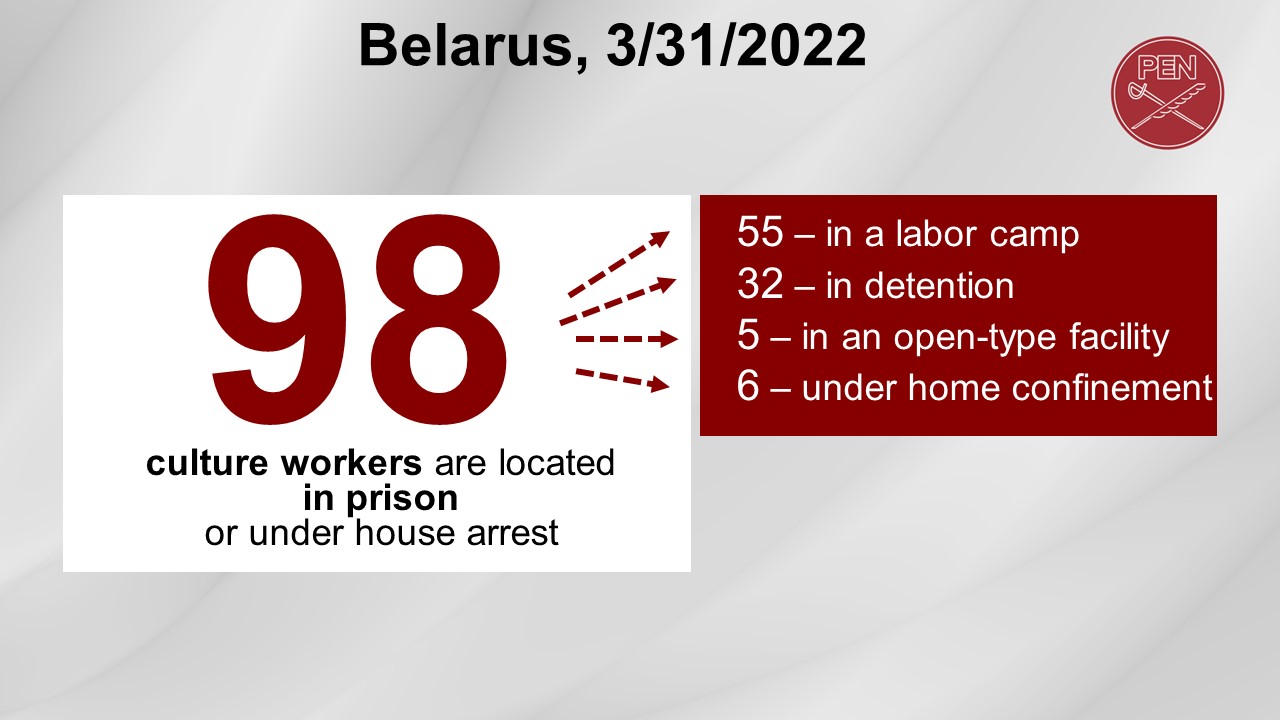

As of March 31, 2022, there are 1110 political prisoners in Belarus. Of those, 79 individuals are cultural figures:

39 of them are in penal colonies:

architect Arciom Takarčuk (sentenced to 3.5 years); artist Uladzislaŭ Makaviecki (2 years); bard and programmer Anatol Chinievič (sentenced to 3.5 years); concert agency director Ivan Kaniavieha (3 years); artist Alaksandr Nurdzinaŭ (4 years of extra labor); documentary filmmaker and blogger Paviel Spiryn (4.5 years); writer and journalist Kaciaryna Andrejeva (Bachvalava) (2 years); artist and animator Ivan Viarbicki (8 years and one month of extra labor); UX/UI designer Dźmitryj Kubaraŭ (7 years of extra labor); artist, former academy of art student Anastasija Mironcava (2 years); drummer Alaksiej Sančuk (6 years of extra labor); culture manager Mia Mitkievič (3 years); writer and social-political Paviel Sieviaryniec (7 years of extra labor); dancers Ihar Jarmolaŭ and Mikalaj Sasieŭ (each 5 years of extra labor); Patron of the arts Viktar Babaryka (14 years of extra labor); actor Siarhiej Volkaŭ (4 years of hard labor); light artist Danila Hančaroŭ (2 years); musician Paviel Larčyk (3 years); poet and publicist Ksienija Syramalot (2.5 years); former students of the aesthetics department at Belarusian State Pedagogical University Jana Orobiejko and Kasia Buďko (each 2.5 years); former student of the Academy of Arts Maryja Kalenik (2.5 years); former student at the architectural department at Belarusian National Technical University Viktoryja Hrankoŭskaja (2.5 years); designer and architect Raścislaŭ Stefanovič (8 years of extra labor); musician, DJ Artur Amiraŭ (3.5 years extra labor); history teacher and social scientist Andrej Piatroŭski (1.5 years); poet, bard and attorney Maksim Znak (10 years of extra labor); musician and cultural project manager Maryja Kaleśnikava (11 years); musician Jaŭhien Piatroŭ (1 year); promoter of history and human rights advocate Taćciana Lasica (2.5 years); author of prison literature and anarcho-activist Mikalaj Dziadok (5 years); musicians Uladzimir Kalač and Nadzieja Kalač (2 years each); promoter of history and blogger Eduard Palčys (13 years of extra labor); author of prison literature and anarcho-activist Ihar Alinievič (20 years of extra labor); musicians Piotr Marčanka, Julija Marčanka (Junickaja) and Anton Šnip (1.5 years each).

5 are at open-type correctional facilities:

Poet and director Ihnat Sidorčyk (sentenced to 3 years); culture manager Lavon Chalatran (2 years); designer Maksim Taćcianok (3 years); poet and founder of the “Honey Prize” literary award Mikalaj Papieka (2 years); researcher at the Centner for the Research of Belarusian Culture, Language, and Literature at the Academy of Sciences Alaksandr Halkoŭski (1.5 years);

26 are located in pre-trial detention or prison:

culture manager Eduard Babaryka (since June 18, 2020); documentary film director and journalist Ksienija Luckina (since December 22, 2020); poet, journalist and media manager Andrej Alaksandraŭ (since January 12, 2021); poet and member of the Union of Poles in Belarus Andrej Pačobut (since March 25, 2021); author and editor, political scientist and analyst Valeryja Kaściuhova (since June 30, 2021); literary researcher and historian of Belarusian literature, essayist and human rights advocate Aleś Bialacki (since July 14, 2021); philosopher, methodologist and publicist Uladzimir Mackievič (since August 4, 2021); former teacher of Belarusian language and literature Ema Stsepulionak (since September 29, 2021); musician Siarhiej Daliviela (since September 29, 2021); musician and violin teacher Aksana Kaśpiarovič (since September 30, 2021); bass guitarist Viktar Katoŭski (since September 30, 2021); librarian Julija Čamlaj (since September 30, 2021); photographer and journalist Hienadź Mažejka (since October 1, 2021); librarian Julija Laptanovič (since October 13, 2021); founder of Symbal.by and cultural project manager Paviel Bielavus (since November 15, 2021); fantasy writer and journalist Siarhiej Sacuk (since Decmber 8, 2021); graphic designer Halina Siemiečka (since December 14, 2021); writer and activist Alena Hnaŭk (since January 11, 2022); musician Vasil Jarmolenka (since Jannunary 25, 2022); theater artist Viera Cvikievič (since Janunary 27, 2022); former Russian language teacher and literature instructor Anastasija Kucharava (since January 31, 2022); librarian and excursion leader Iryna Koval (since February 9, 2022); musical college student Taćciana Barysovič (since February 22, 2022); ceramist Anastasija Malašuk (since February 25, 2022); author, Wikipedia editor and IT specialist Mark Biernštejn (since March 11, 2022); cultural project manager, sociologist and methodologist Taćciana Vadalažskaja (since March 23, 2022).

9 other cultural workers from the list of political prisoners were sentenced between January and March 2022, and once the agreements are made official, they will be moved from pre-trial detention to the place where they are serving their sentence:

- January 14, 2022: musical project maker and typography director Arciom Fiedasienka was sentenced to 4 years in a penal colony.

- January 28, 2022: history reenactor and activist Kim Samusienka was sentenced to 6.5 years in a penal colony.

- February 9, 2022: artist and interior designer Kanstancin Prusaŭ was sentenced to 3.5 years in a penal colony.

- March 3, 2022: nonfiction author and journalist Aleh Hruzdzilovič was sentenced to 1.5 years in a penal colony.

- March 15, 2022: writer, musician, and author in the journal “Our History” Andrej Skurko was sentenced to 2.5 years in a penal colony.

- March 15, 2022: street artist and IT-specialist Dźmitryj Padrez was sentenced to 7 years in a penal colony with extra labor.

- March 16, 2022: nonfiction internet author and blogger Paviel Vinahradaŭ was sentenced to 5 years in a penal colony.

- March 23, 2022: sound operator Vadzim Dzienisienka was sentenced to 2.5 years in a penal colony.

- March 30, 2022: artist Aleś Puškin was sentenced to 5 years in a penal colony with extra labor.

***

Other sentences:

In total, 18 people from the population of culture workers were convicted in the first three months of 2022. Along with those mentioned above, there are 9 others:

-

- January 1, 2022: sound designer Kiryl Salejeŭ was sentenced to 3 years of open-type prison time;

- February 4, 2022: manager of cultural projects, author of fairytales written in captivity, and businessman Alaksandr Vasilevič was sentenced to 3 years in a penal colony;

- February 4, 2022: stage designer Andrej Ščyhiel was sentenced to 5 years in an open-type correctional facility;

- February 7, 2022: comedian and KVN participant Vasiliy Kravchuk was sentenced to 2 years of house arrest;

- February 7, 2022: cellist Ilya Goncharik was sentenced to 4 years in an open-type correctional facility;

- March 2, 2022: history teacher Arthur Eshbaev was sentenced to 3 years in an open-type correctional facility;

- March 25, 2022: amateur actor Constantine Shulga was sentenced to 3 years in an open-type correctional facility;

- March 28, 2022: director Dmitriy Ponteleiko was sentenced to 1 year in a penal colony;

- March 30, 2022: poet, blogger and producer Vlad Savin was sentenced to 8 years of hard labor in a penal colony.

Sixteen more cultural figures are in prison due to criminal convictions or are serving a sentence in open-type correctional facilities. They are: writer, translator, literary critic Alaksandr Fiaduta (in jail since 12.04.2021); author and Wikipedia editor Paviel Piernikaŭ (in jail since 03.11.2021); translator Volha Kalackaja (2 years of open-type house arrest); local historian and activist Uladzimir Hundar (3 years in a penal colony); poet and musician Hanna Važnik (1 year of open-type house arrest); designer Taćciana Minina (4 years of open-type house arrest); cameraman Viačaslaŭ Lamanosaŭ (2 years in a penal colony); culture manager Rehina Lavor (2 years of open-type house arrest); DJ Vital Kaleśnikaŭ (2 years, 3 months and 28 days in a penal colony); history reenactor Vadzim Šylko (in pre-trial detention); musician Kryścina Čarankova (in jail since 03/22/2022); photographer Valeryj Klimienčanka (in jail since 03/24/2022); digital artist Viktar Kulinka (has been in jail since 3/30/2022); graphic designers Uladzimir Jaršoŭ (2.5 years in prison) and Siarhiej Stocki (2 years in prison); Russian language and literature teacher Alena Pucykovič (2.5 years of open-type house arrest).

CONDITIONS OF DETENTION IN PRISON

After almost 2 years of monitoring violations which had occurred in the context of a socio-political crisis, the conditions faced by cultural figures imprisoned for political reasons have not changed for the better. As before, the public is becoming increasingly aware of disturbing levels of neglect, maintenance standards, and administrative pressures on those imprisoned at closed-type institutions run by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Cultural figures are regularly registered as “prone to extremism and other destructive activities”, and their clothes are marked with a yellow tag; the prisoners are deliberately provoked and then placed in a punishment cell or reprimanded; prisoners are “offered” petitions for clemency and threatened with reduced contact with family if they refuse; prisoners are prohibited from communicating with each other; and authorities conduct additional checks and searches of the prisoners’ cells. There are known cases of refusal to provide medical care to prisoners with chronic diseases, which, according to a number of sources, has led to critical health consequences (such as significant loss of vision). Limiting access to broadcasts, prohibiting access to literature, and restricting the right to correspondence are all used as moral and psychological pressure on prisoners. Relatives report that the administration does not allow correspondence to and from the prisoners themselves. This restriction of correspondence can last for weeks, and sometimes months.

As for administrative detentions: in 2020, there was a lot of evidence that the clothes of political prisoners were marked with paint, and those marked individuals later received particularly cruel treatment from authorities. Now it has become known that the police department (the District Department of Internal Affairs) puts the letter “K” on materials related to these cases, meaning that forms of non-statutory treatment will be applied to the prisoner. Detainees at anti-war rallies on February 27-28, 2022 described harsh treatment from authorities, beatings, fourfold overcrowding of cells and even even the convoy’s venting of gas in the shower cubicle.

PERSECUTION FOR ANTI-WAR POSITIONS

On February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation began military operations against Ukraine, part of which was carried out from the territory of the Republic of Belarus.

The status of the Belarusian government as a forced co-aggressor against the people of Ukraine, the threat of involvement of Belarusian troops in an armed conflict, and a referendum on changing the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus: all of these factors co-occurring resulted in spontaneous, peaceful anti-war gatherings. According to the human rights center “Viasna,” on February 27, 2022, the main day of the referendum, 908 people were detained across various Belarusian cities. Detentions took place at polling stations, at the Ukrainian Embassy, near the general staff building in Minsk, and at other places. Among those detained that day were various people working in the cultural sphere.

At the end of February through early March, Belarusian cultural figures who said “No to War” were tried for:

- Participation in anti-war actions. From 27-28 of February, the following people were detained and later tried: translator Volha Kalatskaya (a fine of 2560 Rubles), cultural project manager and activist Viktar Bulaŭski (15 days detention), culture manager and human rights activist Taćciana Hacura-Javorskaja (fined), musicians Jeleŭfieryj Hajko (14 days detention) and Mikalaj Bielanovič (13 days detentiono), artist Dźmitryj Darašenka (15 days detention), actor Maksim Šyško (15 days detention), philologist and Italian language specialist Natalla Dulina (15 days detention), artist and photographer Kaciaryna Malama (15 days detention), photographer Žanna Antonava (15 days detention), students (now no longer enrolled) of the Faculty of Philology of BSU Jaŭhienija and Luboŭ Subat (15 days detention each) and other cultural figures.

- On March 3, after a joint prayer for peace by the mothers of Belarusian soldiers, several people were detained at the exit of the Cathedral in Minsk. Among those detained was Ksienija Fiodarava, a culture manager.

- On March 4, history teacher Larysa Siekieržyckaja was detained at a Babrujsk school for wearing a blue and yellow ribbon in her hair during a lesson. She was fined 2030 Rubles for “participation in an unauthorized mass event.”

- On March 4, poet and bard Hieorhij Stankievič was detained and fined 2240 Rubles. Officially, it was for a photograph with the white-red-white flag as its background (the photo was from five years ago). Really, it was for circulating materials about the war on his website and calling on locals and authorities to contribute at any cost to ending the war in Ukraine.

- On March 8, several residents of Brest, including cultural critic and head of the “Bierahinia” Union Viktar Misijuk, were detained near the monument to the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. The police did not allow anyone to lay flowers at the monument on the eve of the famous poet’s birthday.

- On March 11, Mark Biernštejn, an IT specialist and author who is among the top 50 editors of the Russian-language Wikipedia, was detained for “spreading fake anti–Russian materials”. Mark was among those who made frequent edits to the article “Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine”. After Biernštejn spent 15 days on administrative arrest, a criminal case was opened against him.

The protesters were tried en masse for anti-war actions and expressions: for posters, leaflets and inscriptions saying “No to war”; for anti-war letters sent to state authorities; for anti-war statements on social networks or voiced opinions in a conversation with a friend or a random passerby; for a Ukrainian flag hanging in a window, a yellow-blue scarf or even flowers in a person’s hands.

Priest Alaksandr Baran from the village of Lyntupy, in the Viciebsk Oblast, was detained on March 24 for posting Ukrainian and white-red-white flags on his profile photo on social networks. He spent 10 days behind bars. The Greek Catholic priest Vasil Jahoraŭ, rector of a parish in Bialyničy, Mahilioŭ Oblast, was detained on March 25 because of a sticker on his car with the inscription “Ukraine, I’m sorry”. He spent 3 days in an isolation ward and received a fine of 1,600 Rubles.

It is also known that pressure was exerted on lawyers who had signed a petition stating that, according to the current Constitution, military actions against other countries must not be carried out from the territory of Belarus.

DISMISSALS

Dismissals from cultural institutions on the grounds of dissent are ongoing.

A big blow to the protection of historical heritage came in January, when key employees of the Ministry of Culture in the Department of Historical and Cultural Values were dismissed. Their names are Natalli Chvir and Sviatlana Krajuškina.

In the agricultural city of Okhovo, located in the Brest region, director Alaksandr Dziamčuk was dismissed from the local House of Culture after serving a 30-day sentence for trying to protect 300-year-old oaks at the local cemetery. On January 20, Uladzimir Savicki, who had been directing the Young Spectator Theater in Minsk since 2010, was dismissed. His dismissal may have been in response to a performance of ” Control essay”, which had failed the censorship test of the Ministry of Culture. Academic linguist Alexander Lukashanets was dismissed from the Yakub Kolas Institute of Linguistics on February 23; Lukashanets had condemned police violence after the 2020 elections, and his contract was not extended. At Polack State University, “all conditions were created” such that Alaksiej Lastoŭski, a sociologist and researcher of historical memory, would leave; he has not been working at the university since March 1. On March 15, actress Maryna Zdarankova was dismissed from the Republican Theater of Belarusian Drama, and actor Maksim Šyško, who was previously detained at an anti-war rally in Minsk, was also dismissed. After spending 10 days in pre-trial detention, Andrej Saŭčanka was dismissed from his director position of the BSU theater called “On the Balcony”; he was officially fired on March 15 “by agreement of all parties.” On March 23, it became known that Grodno State University chose not to extend the contract of teacher and doctoral candidate of Historical Sciences Albina Siemiančuk.

There are also known dismissals from the Opera House, the State Philharmonic Society, the Belarusian State University of Culture and Arts, the Belarusian State University, and other institutions.

PRESSURE ON CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANIZATIONS IN THE CULTURE SPHERE

- Compulsory Liquidation

As of March 31, 2022, 382 Belarusian non-profit organizations are listed in the tracking of compulsory liquidation conducted by Lawtrend jointly with the OEEC. In 2021, trials for 316 organizations took place; most of the trials were in the second half of the year. As a result of this process, the civil sector of the country has lost many public organizations representing various types of development, including at least 98 organizations directly related to the sphere of culture. At the beginning of 2022, liquidation processes were beginning for another 65 non-profit organizations. At least ten of them are directly related to the development of culture and ensuring cultural diversity. For example, one of the oldest organizations in the Grodno region, “The Society of Polish Culture in Lidchina,” was recently liquidated. The organization was registered at the end of 1994 and was in engaged in the preservation of cultural memory in the region by installing memorial plaques (including to participants of the 1863 uprising), preserving the memory of famous Polish people, caring for the graves of Polish soldiers, publishing local history books, and studying Polish language and history. There were also trials for the liquidation of the Grodno-based “Club of Polish Folk Traditions”, the Minsk-based “Belarusian Rock League”, an institution for the development of Belarusian music and art called “Ethnotradition”, and a Viciebsk-based eco-cultural and educational community called “A Path from the Varangians to the Greeks”, among others.

On January 22, 2022, a new law came into force which describes the rules of responsibility for the organization of activities and participation of activities of a public association. Included in this law is the rules for liquidating such groups. Now, liquidation carries a fine, an arrest of up to three months, or two years’ imprisonment.

There is an ongoing tendency to make decisions on the self-dissolution of non-profit organizations; this results from the ongoing unfavorable socio-political situation in the country and pressure from the authorities. Lawtrend had collected data on 271 organizations as of March 31. In the first three months of 2022, 46 of them had officially ceased operations, with almost half of the self–liquidated NGOs (22) from the Brest region. Most of the organizations were focused on sports, but approximately 5-7 were culturally oriented. For example, the list of self-liquidated nonprofits includes a charitable foundation called “The Fortification of Brest”, which dealt with the topic of preserving the city’s heritage, as well as a Brest-based cultural and historical public association named after Tadeusz Kosciuszka.

- Reduction of the Number of NGOs with Benefits for Renting Premises

The practice of depriving non-profit organizations of economic potential and preference is ongoing. During 2021, the list of NGOs that were granted benefits for renting premises was reduced on two occasions. According to a resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus, composed on December 27, 2021 and entered into force on March 30, 2022, the list of public associations and foundations with access to a 0.1 price reduction coefficient on rentals decreased significantly. Out of 103 NGOs, only 23 remained on the list; in other words, for 80 organizations now excluded from the list, the cost of rent increased 10 times. Among them are 13 public associations that have a cultural component in their activities, including “The Belarusian Union of Architects”, “The Belarusian Union of Folk Artists”, “The Belarusian Union of Musical Figures”, “The Belarusian Union of Theatrical Figures”, an international public association called “Mutual Understanding”, and other cultural and sports associations, including Jewish community groups.

DISCRIMINATION BASED ON BELARUSIAN LANGUAGE

Belarusian is the state language. Despite this, the violation of the right to use Belarusian language is among the most consistent tracked throughout the entire period of monitoring.

For example, at an event of national significance – the constitutional referendum – the commissioners did not offer ballots in the Belarusian language. In February, on the stands of libraries decorated for the Belarusian Language Day, there was sometimes not even a single book in Belarusian. All seven videos representing the tourism potential of Belarus, each highlighting a particular region or featuring the country as a whole, had only Russian and English versions; this is the case despite how the videos were created by the National Tourism Agency primarily for Belarusians, according to the head of the marketing department.

In Belarus, people are persecuted for “Belarusian-ness”. In a letter from political prisoner Aleh Kuleš described how the administration of the colony informed him that in a correctional facility, everyone must speak exclusively in Russian. Meanwhile, artist Aleś Cyrkunoŭ, who came to a trial in support of artist and performer Aleś Puškin, was detained for use of white and red symbols and for “speaking in the Belarusian language” (direct wording from the protocol). He was sentenced to 15 days in prison.

NEGATIVE TRENDS IN THE CULTURAL SPHERE

- Self-censorship and Anonymity

Due to the potential threat of persecution, many Belarusian writers, musicians, artists, and publishers self-censor their works and statements, or even suspend projects and activities indefinitely. They also sometimes refuse to be public figures and/or write under pseudonyms. For security reasons, they do not sign their works, do not advertise performances nor participation in events, and avoid mentioning themselves in social networks and across cyberspace.

For example, for security reasons, former political prisoner and musician Ihar Bancar and his band Mister X refused the opportunity to play a concert celebrating their new vinyl record. Bancar cited not wanting to “play with fire.” Regarding self-censorship, Zmicier Višnioŭ, founder of the Haliyaf (Галіяфы) publishing house, has mentioned its impact on each book he publishes, regretfully adding that this is unacceptable in the realm of creativity.

- The Recognition of Materials as Extremist

The quantity of materials recognized as extremist is growing; the list is decided by a court and is enforced by the Ministry of Information of the Republic of Belarus according to the list. Since the beginning of the events of August 2020, the list has grown to include independent media, their sites and social network profiles, Telegram chats and channels, logos, videoclips, internet communities, youtube videos, badges, and more.

Also, on February 24, 2022, the court of Brest recognized “Belarusian Radio Racyja”, the country’s first independent FM station, as extremist. Along with economic, social, political, and sports-related programming, the radio station contains material related to culture. Around the same time, a court in the Maladziečna district recognized 15 articles published in its regional newspaper («Rehijanalnaja hazieta») in 2020 as extremist. One of the articles included a music video for Sumarok’s recording of “Chertsi”, which includes footage from protests in Maladziečna. The music video itself does not have an extremist status.

- The Cancellation of Annual Events and the Transfer of Belarusian Cultural Products Abroad

Because of the liquidation of the organization, The Belarusian Language Society was unable to hold its annual public action in support of Belarusian language for the first time in many years. The public action is a national dictation.

In Pinsk, previously planned celebrations dedicated to the 90th anniversary of Polish writer and journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski were cancelled, including the installation of a sign on the building where the writer’s parents worked and where he had attended first grade. Exhibitions and excursions were also canceled. By recommendation of the authorities, as the anniversary (March 4) approached, the organizers were forced to cancel absolutely everything.

Some events and activities changed locations in response to circumstances forced by authorities. For example, in February, the international poetry festival « Grand Duchy of Poetry» was held in Vilnius instead of Minsk. It is also known that the academic book festival “Pradmova”, cancelled in 2021 because of the epidemiological and sociopolitical situation in the country, will take place this year in Tbilisi, Krakow, Warsaw, and Vilnius—but not in Belarus.

- The struggle of pro-government bloggers against Belarusian art

As a result of far-fetched appeals of pro-government activists to the culture department of the Minsk City Executive Committee, in which the activists demanded that authorities take note of certain individual authors, several Belarusian artists have already faced pressure and extra censorship. For example, after a statement alleging the distribution of pornography in Hanny Silivončyk’s exhibition titled “The Disturbing Suitcase”, proceedings began not only against the exhibition itself, but also the Union of Designers more generally, which is where the exhibition had taken place. Its chairman Dźmitry Surski was called in for a conversation, the police came to the Union, and the Ministry of Justice checked the organization’s documents.

In the Palace of Art, in connection with yet another one of these appeals by pro-government bloggers, Ryhor Ivanoŭ’s personal exhibition “The Hour of the Screen” was dismantled ahead of time. The pro-government activist had attacked the exhibition because of Ivanov’s democratic political views. At the same time, Siarhiej Hrynievič’s exhibition “Demography” was closed earlier than the stated deadline “for technical reasons,” which is also interesting because the exhibition had already been limited to works of the artist that had passed through a censoring process. Seven of his works had failed and were thus excluded.

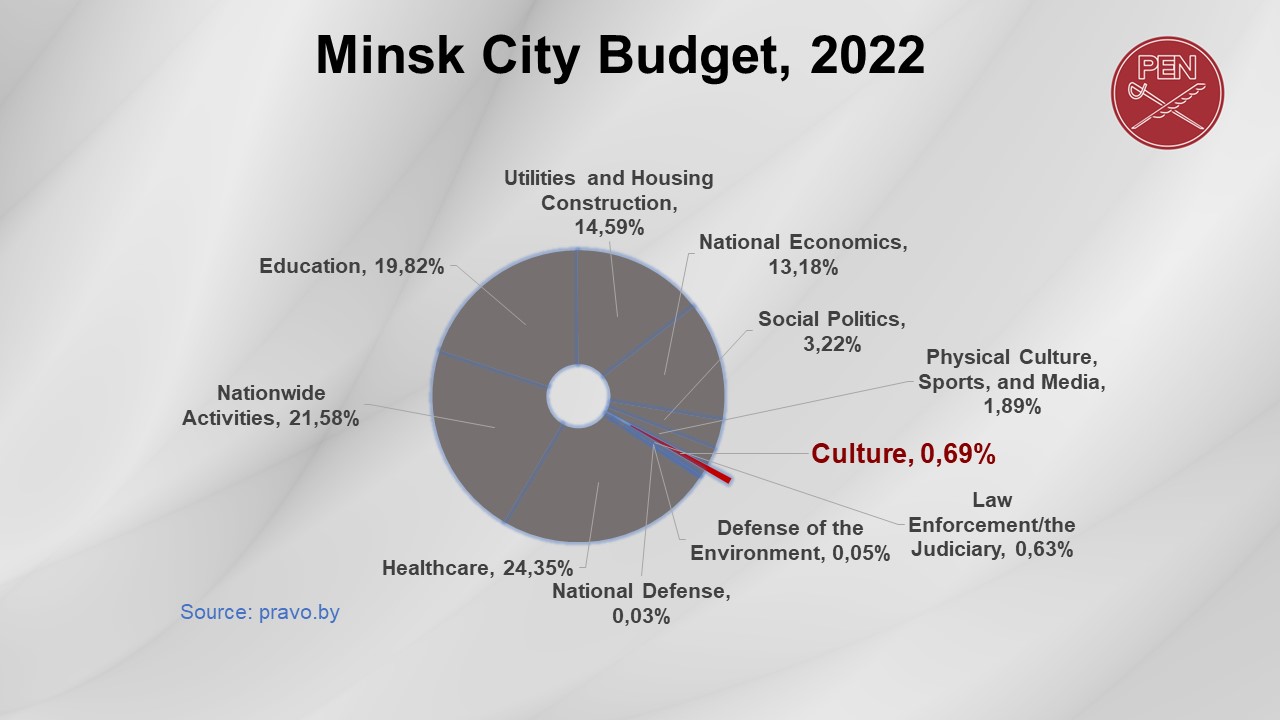

- Budgeting. The cultural sphere has never been and will never be among the top priorities of the government. In January, the annual 2022 budget for the city of Minsk was published. According to the budget, cultural matters in general [culture and art, cinematography, and other issues in the field of culture] collectively account for 69% of the total city budget. They plan to devote 48,883,797 Rubles for the year.

- A Ban on the Profession. “Blacklists” name the cultural figures who are actively prohibited from the free distribution of their creative products, and are well-known in communities of musicians and writers (as well as publishers, starting in 2021). These lists have now begun to impact artists and photographers; politically incorrect authorities refuse to buy any works by blacklisted artists for museum collections and small exhibitions, and their works are subjected to particularly thorough censorship.

- Regime and sanctions, including “cancel culture”. Economic sanctions against Belarus by Europe and the United States, previously imposed as a measure to put pressure on Lukashenka’s illegitimate regime, intensified after the Lukashenka approved of Russia’s attack on Ukraine. This has affected both cultural workers and the consumers of cultural products. For example, due to the rising prices for printing, it has become more and more expensive to buy books in Belarus. Thus, economic sanctions have been supplemented by cultural ones. Much like Russian artists, Belarusian artists have faced cancellation of their concerts in European countries. In general, foreign venues no longer allow Belarusian authors and performers to participate in their events, which affects both the possibility of creative realization of Belarusians and their earnings. Global online platforms like Saatchi Art and Etsy, as well as European payment systems and tools, refuse to work with Belarusian artists and artisans. The actions of the official authorities ultimately serve to impoverish the cultural landscape of Belarus.

- Year of Historical Memory. In Belarus, 2022 was declared “The Year of Historical Memory”. The first on the list of developers and executors of the plan for the year, and for carrying out relevant activities, is none other than the Prosecutor General’s office, followed by the Belarusian Academy of Sciences. After three years (2018-2020) known as the Years of the Small Motherland and the Year of Unity (2021), the choice to use history as a theme is not accidental—the state has launched a program to blame the “Collective West” of the genocide of Belarusian people, and cases have been opened in Belarus concerning the “glorification of Nazism.”

Thus, at the end of March 2021, a criminal case was opened against artist and performer Aleś Puškin. He was charged under part 3 of Article 130, “deliberate actions to rehabilitate Nazism,” because of a portrait he had painted of Jaŭhien Žychar (an anti-Soviet underground worker). In the painting, Žychar holds a machine gun on his shoulder; the work was exhibited at the Hrodna “Center of Urban Life.” According to the prosecutors, Pushkin’s work had “characterized Žychar as a man from the Belarusian resistance, a fighter against the Bolsheviks, and glorified and approved of his actions.” On March 30, 2022, Aleś Puškin was sentenced to 5 years in a strict regime penal colony.

Along with this, there is an ongoing, uncompromising struggle against national symbols (the white-red-white flag and the Pahonia coat of arms). A discrediting of historians is another central theme of this year’s propaganda.

***

We also continue to record circumstances involving persecution for use of symbols. Originally intended to highlight administrative responsibility in persecuting those who use white-red-white symbols, we have since started tracking persecution for using the colors of the Ukrainian flag (yellow and blue).