We have documented a record number of repressive measures against cultural figures in Belarus since August 2020. Culture has always received close attention from the authorities. Unfortunately, they were not offering a helping hand, but instead exercising excessive control. Mass layoffs, banned events, detentions, and arrests no longer surprise anyone. The authorities have begun to destroy a cultural landscape that has been forming for more than a decade.

* This article considers only the situation with theater, without devaluing the importance of all other areas. Also, the text does not contain all the statistics of arrests, dismissals and detentions, and provides only a general analysis of the situation.

Self-censorship as a way of existence

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to a decline in government control over the arts, but since the 2000s, control over culture has already become inescapable. Repressions in the cultural sphere were quiet, consequential and had a “prophylactic nature.” Recommendations for holding events, the need for approvals and touring certificates, officials attending art events, shows for “close friends” and “for everyone” — the system began to actively limit art tools. Step by step, this reality had become commonplace by 2010. This is how the habit of self-censorship was established. Many cultural figures working in state (and even independent) institutions mentally set the “forbidden” zones and consciously limited themselves. No one wanted to become a subject of official censorship nor to tarnish their own reputation and the reputation of their affiliated institution. This practice influenced the formation of cultural identity: art experiments appeared slowly and rarely because many were afraid that they would simply “banned.” The border of the unacceptable formed in the minds of the actors. Freedom was hard to get.

Self-censorship, of course, had positive aspects: many art figures began to expand their artistic tools, which gave an impetus to art development. At the same time, the need to comply with unspoken rules exhausted artists. By 2015, interdisciplinary spaces like CECH, VERH, Korpus 8, Canteen XYZ, Ok16, HIDE, and Lo-FI began to open one after another in Belarus, offering a platform for relatively free art. Artists start to actively find ways to reclaim their creative freedom, but faced some censorship. And this freedom has not pertained to radical art which borders on forbidden content — Cultural figures have just wanted to express ideas close to them in a new language.

Alternative and creative freedom

The Ok16 Cultural Hub, an alternative art space, appeared in Belarus three years ago. Belgazprombank bought the premises of the MZOR plant (Minsk Plant of October Revolution) on the trendy Kastryčnickaja street and the space was set up to meet the creative needs of the Belarusian intelligentsia. It was the first multifunctional loft that became a platform for interaction between contemporary Belarusian actors. Viktar Babaryka [Victor Babariko] initiated the opening of the hub. This year, many of the hub’s employees took part in its election campaign. Maryja Kalesnikava [Maria Kolesnikova] was the art director of “Ok16,” and for a long time fought “only” for free art, like the theater producer Ina Kavalionak [Inna Kovalenok]. However, due to close cooperation with Viktar Babaryka, the curators ended up behind bars. (Maryja Kalesnikava, recognized as a political prisoner, continues to be under investigation, whereas Ina Kavalionak is already free).

The hub was a space where art people learned to interact with each other, find a common language, and reach compromises. This applies to both the literal sharing of space and the establishment of joint projects. For several years of its existence, “Ok16” has actualized modern theater in Belarus and put a new generation of young theatrical figures (Elizaveta Mashkovich, Alexander Adamov, Polina Dobrovolskaya, Evgenia Davidenko, Nikita Ilinchik) on their feet. This theatrical element is only a fraction of what the hub has accomplished.

Freedom of creativity is the main idea necessary in understanding how Ok16 works. This freedom is at the heart of why actors, event organizers and lovers of contemporary art went there. Students, locked in the framework of the academic system, found an opportunity to vent without the close attention of their masters, to choose any materials, and to get competent feedback from the art community. Independent filmmakers actively experimented, mastering the uses of non-theatrical space and site-specific elements. The artists received free «workshops» and an unlimited field for their activity. There was only one limitation: interfering with another’s work was unacceptable.

Cultural hub OK16 offered the opportunity for cultural figures to develop independently; the cultural figures would not have been able to implement their ideas in state institutions. An alternative platform was in demand not only among the art community, but also among the audience. The interdisciplinary space, offering different arts — experimental and traditional, and all relatively free from constraints and internal censorship — attracted the audience with its sincerity.

Viktar Babaryka’s constant presence at events contributed to the unique events at the hub. Viktor Babariko known by many from the TEART festival, as well as from the Art-Belarus gallery, with holds a collection of Belarusian paintings returned to their homeland. It has become clear both creators and those who invest money and energy into creative spaces need art. At the same time, there was no control in creativity — there was only open acceptance and the possibility of development.

Viktar Babaryka’s arrest has been upsetting to many cultural figures. All of his projects contributed to solidarity among those working in theater and allowed for the creation of an alternative art community, which was actively promoting the broadening of artistic horizons. At the time, discussions concerned not only the detained presidential candidate, but also a great art patron who helped many to start and continue their art careers. This arrest could not go unnoticed; it stimulated the cultural community to solidify.

When the investigation committee added 150 paintings and other cultural property from the Belgazprombank collection (valued at about $20 million) to the case of Viktar Babaryka, it became clear that in reprisal against the unwanted leader, the authorities would consider neither the cultural value of the collection nor the interests of the public. The unique collection of artworks is held hostage under political circumstances. The paintings are still “under arrest” and are inaccessible to any viewer.

Plan as a way of pressure

The first wave of the pandemic also contributed to the worsening of the situation in Belarus. In the spring, theatrical figures survived on minimum wages, and independent actors looked for ways to make money. There was practically no support from the state. Theatres often have a plan which predicts how many people should visit the institution, as well as one that calculates how many events the theatre has to hold. During the pandemic, the audience plan was cut, but institutions still needed to fulfill the number of events by the end of the year. The Ministry of Culture and the management of theaters tried to hold performances as an online format and ensure the safety of workers during the first wave of the pandemic. During the second wave of the pandemic, even with coronavirus- infected actors, many theaters continued to operate. Now, the Ministry of Culture alleges that there is no COVID-19 in the theatres. After all, it is not profitable to close cultural institutions. In addition, it’s the Ministry’s internal policy: at least some kind of work will allow employees to be paid a minimal bonus. At the same time, the event plan for the year is an excellent tool for manipulation by state institutions, since failure to fulfill the plan results in fines and a reduction in funding.

Reaction to fraud and violence

After the announcement of the election results, many collectives tried to join the nationwide strike. Some employees of the Janka Kupala National Theatre, The New Drama Theater, The Theatre of Belarusian Drama, The National Opera and Ballet Theater, The Gorky theatre, and other collectives showed gestures of solidarity. However, for many reasons, the strikes did not materialize. The main stumbling block was that employees are required announce a strike two weeks before it begins and make all of their demands directly to the management. In many creative teams, the bosses are valuable people in the art world, who are in fact respected by the team.

Moreover, many theater workers, especially the older generation, did not want to “ruin” institutions, realizing that the state could easily put their activities on a long pause. In this case, the assumption that “all theaters will be closed without another thought” is quite fair. We can expect anything from a state whose development is not geared towards culture. At the same time, a significant part of the troupes has represented the function of art as a mouthpiece for justice, and without a platform and a spectator, it is simply impossible to talk about life in the country both with use of metaphor and directly. The protesters have expressed their support in various creative actions, letters and video messages.

In July, the “Kultpratest” movement formed, and it united people of creative professions. Art figures have spoken publicly about what is happening in Belarus and shared contemporary art reflecting social and political life with one another.

Many actors, directors and other theater workers have actively shown their civic stance at mass protests, including various cultural events. This was the catalyst for several layoffs — the institutional leadership continue to receive orders that are both advisory and mandatory. Often such instructions are verbal or sent to management as letters. Any statement in social networks and even more so in the press is subject to close attention from the Ministry of Culture.

Defeat of Kupalauski

This year the Janka Kupala National Theatre (Kupalauski) was supposed to celebrate its 100th anniversary. On this occasion, the collective was preparing the premiere of the performance “Tuteyshyya” based on the play by Janka Kupala, which had been a popular work in the 1990’s. However, on August 16, the collective of the Kupala Theater signed an open appeal to the Belarusians. In it, the theater workers demanded the initiation of criminal cases against those who gave criminal orders and everyone involved in the crimes. The statement by employees of one of the main national theaters caused a wide resonance and response from civilians who faced brutal violence from security forces.

A day later, on August 17, the theater’s director, Pavel Latuška [Pavel Latushko], was fired, and this dismissal became a catalyst for mass protests in the cultural community. The Kupalaucsy were supported by 112 employees of the National Library of Belarus and by employees of the Mahiliou Regional Drama Theater, The National Opera and Ballet Theater, The Gorky theatre, and even foreign cultural figures, including Russian actors Konstantin Raikin and Oleg Basilashvili.

The team held a meeting with the now-former Minister of Culture Jury Bondar [Yuri Bondar], who had been given an ultimatum: either Pavel Latuška returns to the post of the head of the theatre, or the leading actors and most of the team will resign. The minister, however, appealed to the Kupalaucys to focus on art and not on politics. Spectators and workers from other cultural institutions gathered to support the collective, and they waited at the door of the theater, decorated with white-red-white flags.

The next morning, the Kupalaucys could not get into the theatre building. According to the official version of the story, this day had been set aside to disinfect of the premises and prevent the spread of COVID-19. In actuality, someone was conducting a search. Once in the building, the theater actors found that personal belongings, once in the dressing rooms, were not in their right places. Almost immediately, the STV channel aired a story about the Kupalaucys riotous lifestyle. The footage showed trash cans filled with supposedly empty alcohol bottles and other strange compositions from the scenery that were supposed to show a pogrom. There is no need to talk about how quickly the state renounced the leading cultural figures awarded with all kinds of medals and prizes. The leading state media unfairly discredited the theater collective.

As a result, actors and theater workers wrote over 60 applications for dismissal; many were core members of the team. They included National Artists of Belarus: Zoja Bielachvoscik [Zoya Belokhvostik] and Arnold Pamazan [Arnold Pomazan], Honored; Artists of Belarus Alena Sidarava [Alena Sidorova], Julija Špileŭskaja [Yulia Shpilevskaya], Ihar Dzianisaŭ [Igor Denisov], Natallia Kačatkova [Natalya Kochetkova], Heorhi Maliaŭski [Georgy Malyavsky]; famous actors Pavel Charlančuk [Pavel Kharlanchuk], Sviatlana Anikiej [Svetlana Anikey], Dzmitry Jasienievič [Dmitry Yessenevich]; and artistic director Mikalaj Pinihin [Nikolai Pinigin]. Moreover, a little later, Zoja Bielachvoscik was fired from the Belarusian State Academy of Arts and was not allowed to finish teaching her students, who are due to finish their studies this year.

Deputy Minister of Culture Valery Hramada [Valeriy Gromada] was appointed acting director. A few months after the incident with the Kupalauski theater, Minister of Culture Jury Bondar was also replaced by an ex-presidential aide — the inspector for the Brest region, Anatol Markievič [Anatoly Markevich]. Pavel Latuška, having entered the Coordination Council, received various threats for a long time and was forced to leave the country. By means of various detentions of members of the Coordination Council, the authorities tried to disorganize its work and demoralize the team. A little later, Latuška clarified that he was given “an ultimatum: to leave the country or to be prosecuted.”

On its 100th anniversary, the stage at the Janka Kupala Theatre was empty, and the actors at regional theaters received offers from the Ministry of Culture to audition to join Kupalauski. At the moment, information about who joined the renewed collective of the theater has not been published anywhere.

The choreographic ensemble “Charoški” [“Khoroshki”] and the concert orchestra led by Mikhail Finberg has since performed on the Kupalauski stage; there were approximately ten people in the hall. We can assume that the workers of these groups were also given an ultimatum despite the official statements suggesting otherwise. This was also the case for the National Choir of the Republic of Belarus named after G.I. Citovič. The choir has 13 unperformed concerts left this year, which they have to work out according to their plan. The artists refused to perform on the Kupalauski stage and offered to give visiting concerts in regional cities as an alternative. However, their offer was rejected.

Massive layoffs

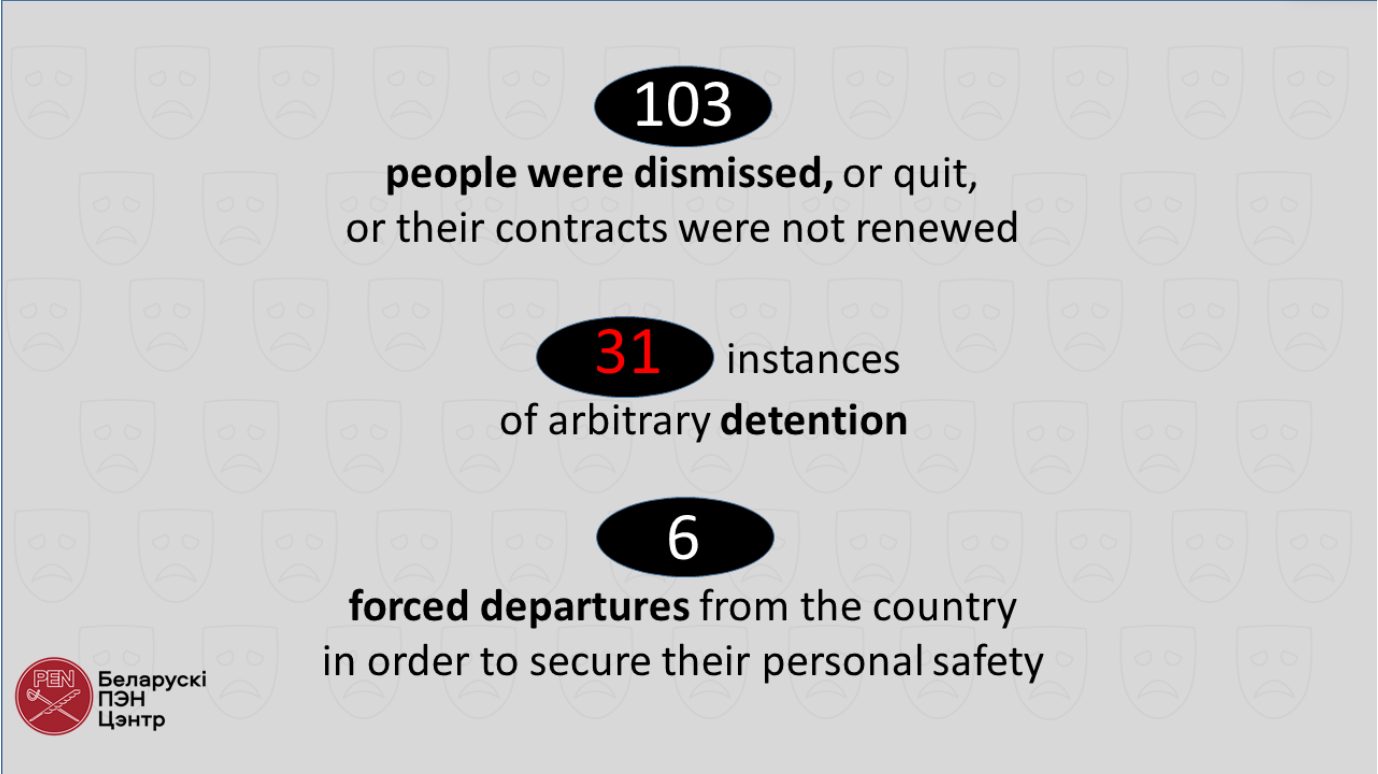

Many collectives expressed solidarity with the actions of the Kupalaucys, and this served as a catalyst for the dismissals of leading actors, directors, and theater staff throughout Belarus. This was expressed in letters from employees to the Ministry of Culture, the Council of Ministers, the and Belarusian Union of Theater Workers, as well as in various creative actions and video messages condemning acts of violence from the security forces.

The dismissal of Andrej Novikaŭ [Andrey Novikov], head of the Mahilioŭ Regional Drama Theater, has received considerable attention. Mr. Novikaŭ led the institution for 20 years. He has organized one of the best international festivals, the Youth Theater Forum “[email protected]”, and made the regional theater one of the centers of theatrical production in Belarus. Authorities justified the dismissal, citing how he had refused to fire employees showing an active political position.

Foreign colleagues also reacted to the dismissal of Andrej Novikaŭ. For example, the famous Russian theater critic Pavel Rudnev said that he rarely meets such theater managers as the leader of the Mahilioŭ drama theater (Novikaŭ), and that it is unforgivable to get rid of such incredible managers. And this is accurate — Andrei Novikov has been creating an environmentally friendly atmosphere in the theater for years by inviting young directors, realizing the risks, competently fulfilling the state program, and carefully adding box-office comedies to the repertoire.

The main director of the theater, Uladzimir Piatrovič [Vladimir Petrovich], also suffered due to participation in social and political life. Mr. Piatrovič created a performance based on one of the first stagings of the book «Second Hand Time» by Sviatlana Aleksijevič [Svetlana Aleksievich]. He was detained during an excursion and arrested for three days. Volha Siemčanka [Olga Semchenko], head of the theater’s literary section, was also detained while participating in peaceful processions.

Specialists from the Mahilioŭ Regional Museum named after Maslennikaŭ have expressed solidarity with the theater staff. They wrote an appeal to the head of the culture department of the Mogilev regional executive committee. Unfortunately, this did not affect the situation in any way.

Solidarity concerts to support the peaceful protesters were held near the National Academic Bolshoi Opera and Ballet Theater. Before the start of an opera on October 27, the hymn “Mahutny Boža” sounded in the hall. Immediately after the performance, artists who have spoken out against violence and lawlessness in the country were dismissed from the opera house, among them the first chair violin Rehina Sarkisava [Regina Sarkisova], violinist Ala Džyhan [Alla Dzhigan] and viola player Aliaksandra Paciomina [Alexandra Potemina]. The honored art worker and conductor Andrej Halanaŭ [Andrei Galanov], as well as the winner of the Francysk Skaryna medal and opera soloist Illia Silčukoŭ [Ilya Silchukov] were also dismissed. The theatre troupe collected over 200 signatures supporting those who had been fired. People said that “with bitterness, they are watching the higher officials’ outrageous indifference to the collective of the Bolshoi Theater of Belarus”.

Some cultural figures began to leave theaters by choice. For example, actors Andrej Novik and Mikalaj Stańko [Nikolai Stonko] left the Republican Theater of Belarusian Drama. Novik has said that it is impossible “to go on the stage of the state theater while friends, colleagues, teachers, idols are thrown out into the street just because of their civil position”. Another RTBD actor has come out against censorship in the theater and against the control of the Ministry of Culture, which began to send its representatives to performances. Such “auditors” are supposed to monitor and suppress any signs of solidarity and manifestations of citizenship.

Employees of the Center for Experimental Directing at the Belarusian State Academy of Arts also signed letters of resignation due to their civil position.

Twelve employees of the New Drama Theater joined the strike and refused to work on the stage. However, the management laid claims for recovery damages of 15,000 BYN for spectacles that were allegedly never performed. According to the law, the actor who disrupts a performance must compensate for the financial damage caused to the theater. The precedent is partly comical, because the damages included the cost of personal protective equipment (masks) which had allegedly never been distributed to the spectators. The court was on the side of actors. However, after the trial, artists still filed applications for dismissal. The management’s actions reflect what has been happening in the collective for many years: not so long ago, there was a scandal with the canceled premiere of Jura Dzivakoŭ [Yura Divakov]. The production of “The Bedbug”, based on the play by Vladimir Mayakovsky, was interrupted during rehearsals, and the reason was the artistic leadership’s distrust of the director’s work process. To the bosses, the work seemed too “avant-garde”. At the same time, both the theatre community and other theaters that invite him to direct have no doubts about Jura Dzivakoŭ’s professionalism.

For “refusal of labor obligations” (in fact, participation in a strike), the chief director Henadź Mušpiert [Gennady Mushpert] was fired from the Hrodna Regional Drama Theater. Mr. Mušpiert has worked there for over 26 years. A little later, news broke about the dismissal of another director at this theater, Honored Artist of Belarus Siarhej Kurylenka [Sergei Kurylenko]. During the protests, he was detained with his wife Valiancina Charytonava [Valentina Kharitonova]. Their colleagues found out about this during the evening performance and refused to continue performing. The management forced the artists to write explanatory notes, and Lizavieta Milincevič [Elizaveta Milintsevich], who disagreed with the management, was fired.

The situation got out of control and the repression became more and more absurd. Maksim Karžycki [Maxim Korzhitsky], a former actor of the Jakub Kolas National Academic Drama Theatre, was arrested for 10 days because he had set a candle near the monument to the Soldiers-Internationalists in honor of the murdered Raman Bandarenka. Ihar Andrejeŭ [Igor Andreev], an actor at the Gorky National Academic Drama Theater, was also detained during a reading in memory of Raman Bandarenka. Aliaksandr Raćko [Alexander Ratko] from the Homel State Puppet Theater was detained after he tried unsuccessfully to swim across the Nioman River in an attempt to avoid detention.

The arrest of Aliaksandr Ždanovič [Alexander Zhdanovich], an actor at the Gorky Theater, caused further resonance. Aliaksandr is known for his role as Maliavanyč from the children’s TV show “Kalychanka”. A little later, information appeared regarding his dismissal from the St Elisabeth Convent, but the actor wrote on Facebook that he was not in legal relations with the monastery and therefore could not legally dismiss him.

The seriousness of the ongoing situation continues to grow despite the absurdity of certain repressive measures. Theatre figures who take part in the protests are under active pressure from the Ministry of Culture. Moreover, some actors have been injured during the peaceful marches. Alena Hironak [Elena Girenok], an actress at the Film Actor’s Studio Theater, was detained during the protests and beaten; she suffered blows to her face and head. And in December, during a Sunday protest march, Illia Jasinski [Ilya Yasinsky], an actor at the Republican Theater of Belarusian Drama, was detained. The artist was severely beaten and taken to the hospital with two fractured vertebral processes. Such an injury could cause disability and result in the end of his acting career. It is worth noting that the actor is fine now.

Many theater workers have recorded video messages and signed open letters supporting peaceful protesters and an end to the violence in their country. Authorities have drawn varying degrees of attention to the collectives and their positions, but the theaters never stopped receiving letters from “above” with hints that expressing a civil position during working hours carries consequences. Any open display of opinion is still regarded as a reason for dismissal, often because it is a “violation of labor discipline” and “refusal to fulfill work obligations.”

All the while, the Ministry does not reduce the plans for events and performances despite COVID-19 and the lack of spectators. The unofficial reason is that many actors have demonstrated active citizenship in August and September.

The blow from classic creators

Detentions, arrests and dismissals have become our reality, which is no longer as shocking as it once was. It is possible to ban protest actions, but not to ban the works of Janka Kupala, Jakub Kolas, Vasil Bykaŭ, Uladzimir Karatkievič and other classics writing about the national idea. It is absurd and practically impossible, and yet it has happened in recent months: in the Grodno Regional Puppet Theater, the production of Janka Kupala’s Poem Without Words was canceled. According to the official story, one of the actors was diagnosed with a coronavirus. However, the actors assume that their decision to express words of solidarity before the performance based on the work of Kupala was to blame.

The concept of self-censorship is already being rethought, and the process of solidarity in the art community is irreversible, as it began long before the events of 2020. The state’s love for “traditional art” turns against the art itself. Schoolchildren are taken to the theater for performances based on classical texts, but they are not only about love, friendship and patience; it turns out that Ostrovsky also writes about corruption, Chekhov about pseudo-specialists, and Gorky about the problems of the regime.

No matter how the state tries to level the civic positions of collectives, it is practically impossible to do so. Even if the intensity of the statements decreases for some time, their essence does not change. The audience knows what is happening with theatre institutions, and even in children’s performances about justice, they see political implications that the troupe does not lay out. Deceiving the viewer with a picture of “stable work” will not succeed, and theater workers already know full well what is happening inside. After the situation with Kupalauski, when the authorities were able to discredit one of the main national theatre groups, the rest of the troupes began to choose safer ways of expressing a position of solidarity. All of this is happening due to the pressure from the Ministry of Culture.

Theater employees actively demonstrate their civic stance at peaceful protests. However, most of the teams do not have an official position for fear of destroying the institutions in which they work.

Download the pdf-version of the report