About the monitoring

In August 2019, the Belarusian PEN Center began preparing comprehensive research on the implementation of cultural rights in Belarus. We developed a special approach to studying the situation and collecting information, taking into account the problematic nature of the Belarus cultural field and the lack of research on implementing cultural and human rights for cultural figures. In October 2019, the Belarusian PEN Center started a systematic collection of information, which would document actual violations and monitor their quantitative and qualitative aspects.

Initially, as an association of writers, the Belarusian PEN Center planned to monitor the implementation of cultural rights just in the production and consumption of literary works. However, we have realized that there are problems in other spheres of culture, and because no one has kept records in any of those areas, the Belarusian the PEN Center has decided to record violations in other spheres of culture, such as music, cinema, design, fine arts.

The purpose of the monitoring: to systematically document human rights violations against cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus.

Research subjects:

- subjects of violated rights, their characteristics;

- vulnerable areas of cultural rights;

- real and formal reasons for violation of rights or discrimination;

- problems in legislation and enforcement practice leading to violation of rights;

- possibilities and mechanisms for restoring violated rights.

The monitoring covers the whole territory of Belarus and focuses on cultural workers in various fields. The collection of information is carried out based on an analysis of public republican and regional sources of information and of state and non-state media (15 media in total); an. analysis of social networks and relevant telegram channels of creative communities (15 in total); cooperation with creative associations and initiatives throughout Belarus (about 20 partner contacts); communication with Belarusian human rights organizations in partnerships; personal appeals of cultural workers and their own active observations, like in courts cases in relation to cultural figures; and thematic round tables and expert discussions.

Expectations and reality of 2020

On the one hand, the Republic of Belarus is a signatory of all the main international documents related to the culture, and the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus recognizes and guarantees fundamental cultural rights. In particular:

- The state shall bear responsibility for preserving the historic, cultural and spiritual heritage, and the free development of the cultures of all the ethnic communities that live in the Republic of Belarus (art. 15);

- The right to preserve one’s ethnic affiliation, right to use one’s native language and to choose the language of communication. The state shall guarantee the freedom to choose the language of education and teaching (art. 50);

- The Constitution guarantees the right to take part in cultural life and sets out the obligation of the State to contribute to the development of culture, scientific and technical research for the benefit of common interests (art. 51);

- Citizen are the right to receive, store and disseminate complete, reliable and timely information of cultural life (art. 34);

- Constitutional provision on the intellectual property guarantees the protection of moral and material interests of creators of artistic works (art. 51).

On the other hand, the provisions of the Constitution are developed in laws and bylaws. The Code of Culture, the main statute for cultural life, came into force in February 2017. Its development was meant to eliminate accumulated contradictions and harmonize legislation, including the norms of international documents and conventions ratified by Belarus. However, as the practice shows, the Code itself creates conditions for systemic violations implemented in law enforcement practice.

Fragmentary borrowing of international law elements and, in parallel, maintaining the old paradigm of ideas about the management of culture resulted in many provisions of the Code of Culture being contradictory. For example, recognizing the freedom of creativity, the Code of Culture includes a procedure for “confirming the status of artist”.

Experts and cultural activists note several problems related to both the legislation regulating cultural activities and the particularities of law enforcement practice. Among them:

-

The restrictive nature and selective application of certain norms. The confusion and vagueness of Belarusian legislation contribute to the selective application of the rules of law. It makes it possible to use the same rules of law for both prohibitions and permits in different cases.

-

In law enforcement practice, state cultural institutions always have an advantage, while selectivity applies to non-state institutions. The government almost entirely excluded non-state organizations from the practice of public support, subsidies, and preferences, which apply (with few exceptions) only to state cultural institutions.

-

Existing legislation leaves room for discrimination and ignores great cultural diversity. The principle of non-discrimination of various social groups and communities is not directly established by Belarusian legislation, although its basic principles guarantee it (ensuring the right of everyone to take part in cultural life, ensuring equal rights and opportunities for citizens, preventing the establishment of advantages and privileges, etc.). Some provisions of the Code of Culture, which provide for special conditions for access to culture for particular groups, speak only of people with disabilities, residents of rural areas, and youth. However, the Code does not mention other social groups: gender, national, subcultural, etc., although in law enforcement practice these groups often face unreasonable restrictions.

-

Obstacles and very limited opportunities for gaining access to international funding. First, the authorities strictly regulate the receipt of foreign grant aid, including the list of purposes for which it can be aimed. Secondly, the receipt of such assistance for many non-governmental organizations is associated with problems of an ideological nature and problems of extreme subjectivity of state bodies when issuing permits and other bureaucratic formalities.

-

Civil society organizations have limited capacity in decision-making and policy-making in the field of culture. NGOs have only an advisory voice and should be invited to the discussion by state bodies, although the Code of Culture fixes the forms and mechanisms of interaction between public and state structures.

Therefore, the Belarusian legislation in culture lays down discriminatory mechanisms at the institutional level and limits the possibilities of some groups and organizations by providing preferences to others. Most of the mechanisms are fixed not at the legislation level, but by law enforcement practice, selective or subjective interpretation of norms, and the ability to appeal to different legislative acts regulating the same area.

The identification and study of cases of human rights violations against cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus have been necessary to make the cases visible in the cultural space and to bring them to the discussion in professional environments and public discourse. We have wanted to make it a subject of discussion with authorities in order to interact and rectify the situation.

That was the plan and our vision for the monitoring of results based on the “habitual” Belarusian reality in the cultural sphere as of October 2019. However, the peculiarities of the political situation of the last year have been marked with several new, serious challenges. Public protests against the “deeper integration” of Russia and Belarus in December 2019-January 2020, the way in which the Belarusian state has ignored COVID-19 since February 2020, the preparation and conduct of the 2020 presidential elections, as well as the post-election period— these have all caused a radical change in the violated rights of cultural workers and cultural rights in the country. At the same time, it is a great success that the Belarusian PEN Center had already planned, prepared and organized data collection in advance of these events. It made it possible to document the situation of cultural figures and cultural institutions and organizations during the socio-political and legal crises of 2020.

Main monitoring results

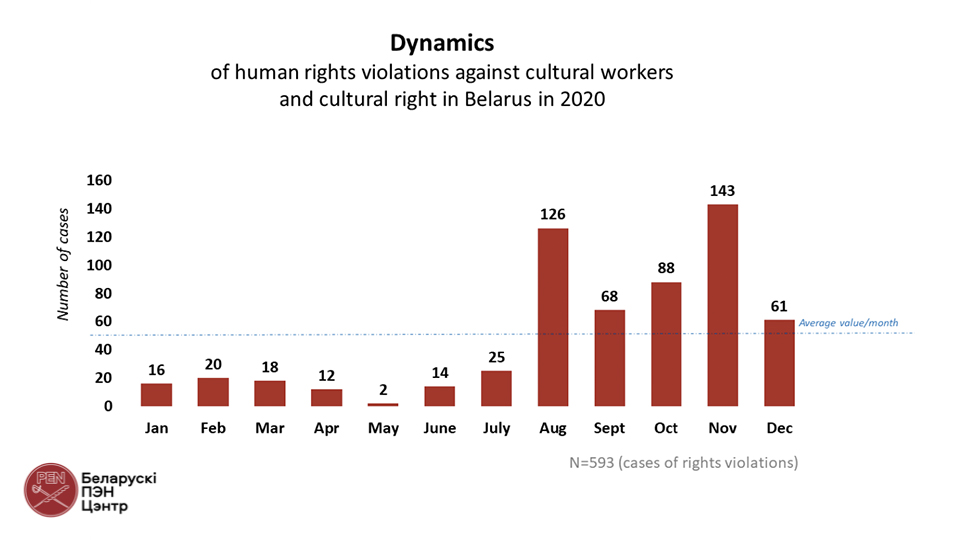

The number of documented cases of human rights violations against cultural figures and cultural rights reached 593 in Belarus in 2020. We also understand there are cases we haven’t covered since they haven’t been publicized or haven’t been interpreted as violations.

The main increase in cases of human rights violations against cultural workers has been documented since August 2020. During the first 7 months of the year, the number of registered cases had not exceeded 25 per month. Starting in August, the number increased rapidly. The number of detentions had reached a peak in November, during which there were 143 cases of human rights violations against cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus.

The main increase in cases of human rights violations against cultural workers has been documented since August 2020. During the first 7 months of the year, the number of registered cases had not exceeded 25 per month. Starting in August, the number increased rapidly. The number of detentions had reached a peak in November, during which there were 143 cases of human rights violations against cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus.

Characteristically, during the monitoring of human rights violations, three groups of subjects have formed, against whom violations have occurred:

Characteristically, during the monitoring of human rights violations, three groups of subjects have formed, against whom violations have occurred:

1. Private persons: direct cultural workers, whether writers, artists, musicians, students of relevant institutions or other creative people, as well as those who do not belong to any of the creative groups but suffered in response to the artistic act they produced. For example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs dismissed an employee because he had posted poems on social media. The poems condemned violence following the election in August 2020. In another example, an activist of a political party received additional punishment for an act of art protest in the courtroom.

We documented 494 violations against cultural workers and 6 violations against people who performed a particular artistic activity during the monitoring period.

2. Organizations and communities. This group includes both organized unions, communities or legal entities: for example, Francysk Skaryna Belarusian Language Society, Belarusian PEN Center, Janka Kupała National Academic Theatre, Hrodna Regional Drama Theater and others; shops “Kniaz Vitaŭt,” “Cudoŭnaja krama” and others; musical groups VAL, ŠUMA [SHUMA], Laudans and others; festivals “Listapad,” Watch Docs Belarus and “January Music Nights” and others, as well as communities of artists, independent musicians, theater venues and other informal creative associations in general.

Total: 67 cases.

3. Cultural heritage: facts of discrimination and defamation of the Belarusian language, facts of harming buildings that are historical heritage, and the defamation of symbols that have historical significance and have gained relevance in the current post-election political situation in the country.

Total: 26 cases.

84% of documented human rights violations affected private persons, 11% impacted organizations and communities, and 4% affected cultural heritage, as shown in the chart below. There is no reason to analyze the distribution of cases by months from the point of view of the subjects of violated rights since these are quite spontaneous events and, again, we do not have a complete picture of the current situation.

After we analyzed all cases of violations, we noted that in relation to individual subjects, in each situation, from 1 to 8 violations could be recorded.

After we analyzed all cases of violations, we noted that in relation to individual subjects, in each situation, from 1 to 8 violations could be recorded.

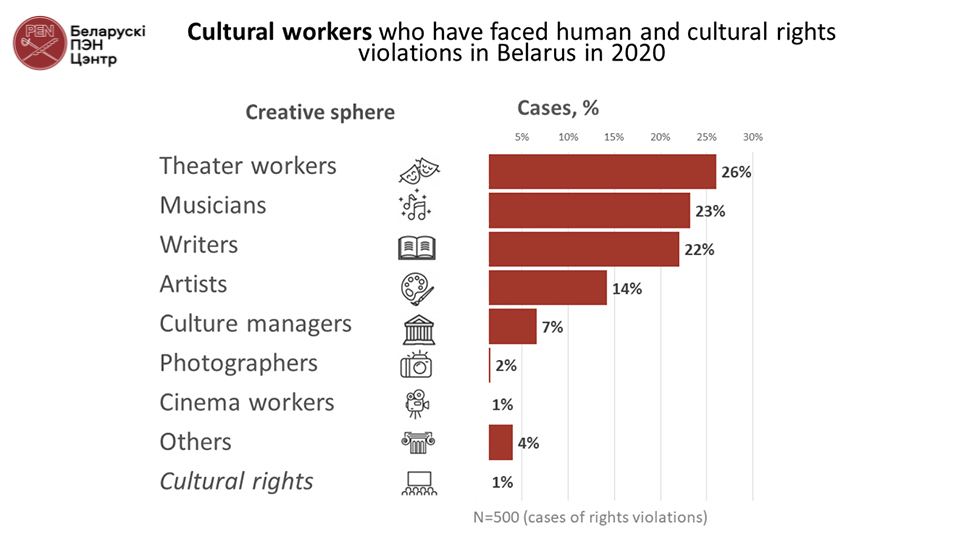

The largest number of violations occurred among theater workers, musicians and writers, as shown in the above graph. Theater workers are present in such numbers because actors, actresses, or other theater employees have been detained during peaceful protest marches, were accidentally on the street in the wrong place and at the wrong time, and sometimes participated in a large-scale wave of solidarity that has touched entire theatre troupes, who have spoken out against violence in the country and supported their repressed colleagues, as happened with Kupalaucy, Hrodna, Mahiliou, New Drama Theaters, and the Theatre of Belarusian Drama. Five musicians have been dismissed from the National Opera and Ballet Theater after the wave of solidarity. Musicians are the second largest group of victims of rights violations. In addition to the above mentioned, a wave of repression has affected drummers, who actively supported and participated in the rhythm of numerous street processions; furthermore, violations have also been against members of bands that have given street concerts in courtyards in support of the people. There are also several cases of copyright violation and other circumstances. In this distribution, writers take third place. Among them are those who have been detained at the protest peaceful marches, those who have read poetry at courtyard meetings, and cultural workers for whom the administration did not renew their employment contracts. Some people have been forced to resign due to their active citizenship. The Institute of History of the National Academy of Sciences has tried to get rid of employees who have protested against police violence and of other colleagues who quit in solidarity with them. We should mention cases of censorship when authorities have canceled presentations of a book by a writer or historian, refused to provide a venue, or painted over words in a poem that a prisoner writes to his family.

The largest number of violations occurred among theater workers, musicians and writers, as shown in the above graph. Theater workers are present in such numbers because actors, actresses, or other theater employees have been detained during peaceful protest marches, were accidentally on the street in the wrong place and at the wrong time, and sometimes participated in a large-scale wave of solidarity that has touched entire theatre troupes, who have spoken out against violence in the country and supported their repressed colleagues, as happened with Kupalaucy, Hrodna, Mahiliou, New Drama Theaters, and the Theatre of Belarusian Drama. Five musicians have been dismissed from the National Opera and Ballet Theater after the wave of solidarity. Musicians are the second largest group of victims of rights violations. In addition to the above mentioned, a wave of repression has affected drummers, who actively supported and participated in the rhythm of numerous street processions; furthermore, violations have also been against members of bands that have given street concerts in courtyards in support of the people. There are also several cases of copyright violation and other circumstances. In this distribution, writers take third place. Among them are those who have been detained at the protest peaceful marches, those who have read poetry at courtyard meetings, and cultural workers for whom the administration did not renew their employment contracts. Some people have been forced to resign due to their active citizenship. The Institute of History of the National Academy of Sciences has tried to get rid of employees who have protested against police violence and of other colleagues who quit in solidarity with them. We should mention cases of censorship when authorities have canceled presentations of a book by a writer or historian, refused to provide a venue, or painted over words in a poem that a prisoner writes to his family.

Structure of violations

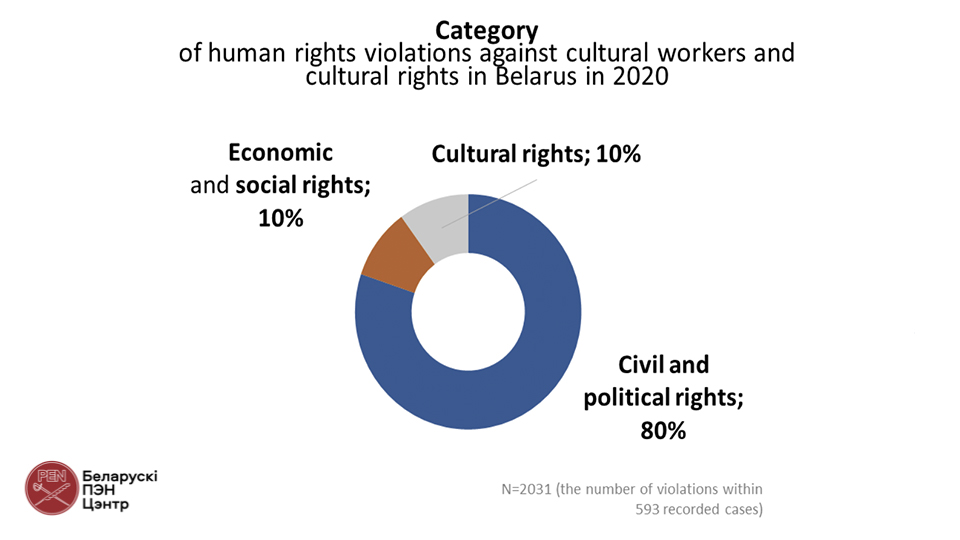

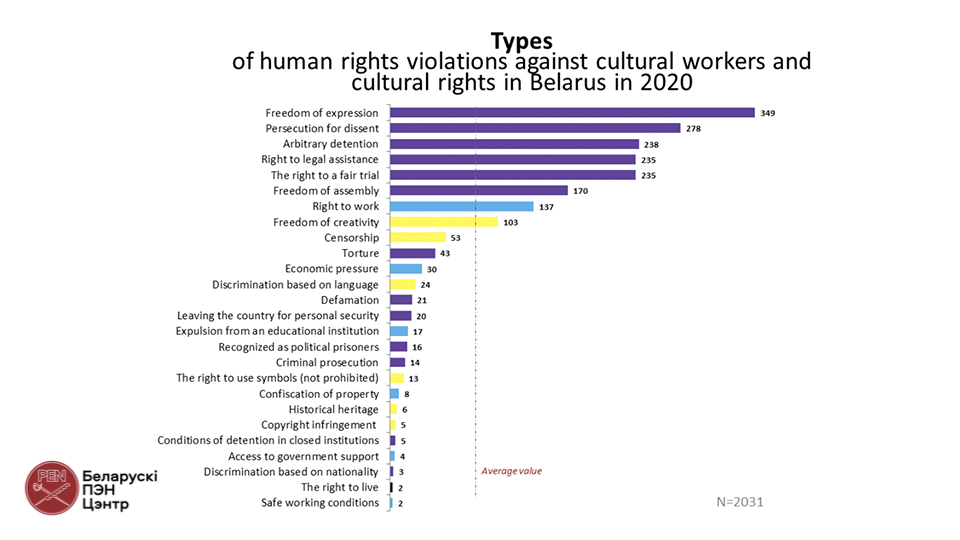

In the general list of violated rights, there are 26 items that can be divided into three categories: civil and political rights and freedoms, economic and social rights, and cultural rights.

It has already been stated that when the Monitoring of Human Rights Violations concerning cultural workers and cultural rights was planned and started, the reality of life in Belarus was different. Back then, violations that representatives of creative professions faced and those that citizens of the country observed were primarily cultural rights: the presence of “blacklists” of musicians and writers; acts of censorship affecting the work of photographers, artists, film industry workers, etc.; problems with touring permissions; posting photographs and musical works on state channels without attribution; and issues of ensuring constitutional bilingualism. These examples illustrate the sphere of cultural rights violations. These constitute the “expected and usual” types of violations in the context of the cultural sphere in Belarus.

However, the reality of 2020 has significantly changed the “usual” picture and place of creative expression so much that the main group of violated rights in the context of creativity has shifted to basic civil and political rights and freedoms.

However, the reality of 2020 has significantly changed the “usual” picture and place of creative expression so much that the main group of violated rights in the context of creativity has shifted to basic civil and political rights and freedoms.

Right to live

We regretfully state that two cases of the right to life fell into the focus of this monitoring.

— Kanstancin Šyšmakoŭ, the director of the Bagration War History Museum (Vaŭkavysk city, Hrodna region) refused to sign the protocol of the election commission. On August 18, he was found dead. Konstantin had 29 years old.

— Raman Bandarenka, a 31-year-old artist and Minsk resident, died in a hospital on the evening of November 12, 2020. According to media reports, unidentified masked men came to his neighborhood to remove protest flags and ribbons. They beat him after a verbal confrontation. Police then took him away in a van. Several hours later, Raman Bandarenka was transferred unconscious to hospital with head injuries and a collapsed lung. Surgeons were unable to save him

At the time of writing, the relatives of both victims and society continue to insist on a proper investigation.

Political prisoners

As of January 1, 2021, 169 people have been recognized as political prisoners in Belarus. Among them, there are 15 people whom we consider cultural figures for the purposes of this monitoring: writer, public and political figure Paviel Sieviaryniec [Pavel Sevyarynets]; lawyer, poet, songwriter Maksim Znak; poet and director Ihnat Sidorčyk; anarchist activist and author of prison literature Mikola Dziadok; musicians Maryja Kalesnikava [Maria Kolesnikova] and Aliaksiej Sančuk [Alexey Sanchuk]; patron of the arts Viktar Babaryka; culture managers Aliaksandr Vasilevič [Alexander Vasilevich], Eduard Babaryka and Dzianis Čykaleŭ; Ksenia Syramalot, a student of the Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences, BSU; Jana Arabiejka and Kasia Budźko, students of the Faculty of Aesthetic Education, BSPU; Maryja Kalenik, a student of the Faculty of Exhibition Design at the Academy of Arts; and Victoryja Hrankoŭskaja, a former student of the Faculty of Architecture at BNTU.

«Top-5» violations

Freedom of expression (349 cases) is the most documented human rights violation against cultural figures, as shown in the graph above.

Freedom of expression (349 cases) is the most documented human rights violation against cultural figures, as shown in the graph above.

Next are prosecution for dissent, arbitrary detention, the right to legal assistance and the right to a fair trial (235 to 278 cases). These types of violations are within the category of civil and political rights and freedoms.

The right to work takes the 7th place of the most violated rights (137 cases), and the 8th position is a violation of freedom of creativity (103 cases), a cultural right.

“Freedom of expression” is a right that has been violated more often than others, both in the total volume of documented cases and in cases concerning private persons. In 593 cases of human rights violations against cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus, the right to freedom of expression was violated 349 times. When cultural figures have gone to peaceful meetings or a permitted picket in support of any of the presidential candidates, or have taken part in a peaceful protest march, a chain of solidarity, a courtyard concert, or a memory action near the monument to the deceased, the right to freedom of expression has consistently been violated. This basic right was also violated when authorities pursued teachers, a theater troupe, or a group of students who recorded a video message condemning the violence taking place on the city streets and demanding new, fair elections.

«Persecution for dissent» takes second place in the ranking of human rights violation frequencies. The cases are universally those of persecution for opinions which oppose the state. Persecuting cultural figures for their opinion, authorities have fired undesirable persons (impacting the right to work), expelled them from educational institutions, confiscated their property, summoned them to the district police department, initiated criminal cases, and used social service authorities to threaten to override parental rights. In short, authorities have been creating situations that force people to leave the country in order to ensure ideological security.

«Arbitrary detention» is the third most frequent violation. This includes cases when representatives of the cultural community have been detained during peaceful protest marches, after courtyard concerts, and during meetings with unknown persons who have broken into their houses or apartments without identification marks, without introducing themselves, and without showing documents.

«Rights to legal aid and a fair trial» are the fourth and fifth most frequent violations and go hand in hand in our monitoring. The legal situation in Belarus in 2020 can be called a default, rife with kidnappings, beatings, and convictions for the “wrong color scheme” of dresses or being in the wrong place or for the clothes of the “wrong” colors hanging on the balcony. Without examining merits, judges award arrests, give monetary fines and decide criminal cases. Representatives of the power structures act as witnesses on such courts. They are allowed to remain

in the courtroom in balaclavas and answer to any name. If the accused has a lawyer, then the lawyer likely has at most 5 minutes to communicate with the client and to familiarize himself with the case materials.

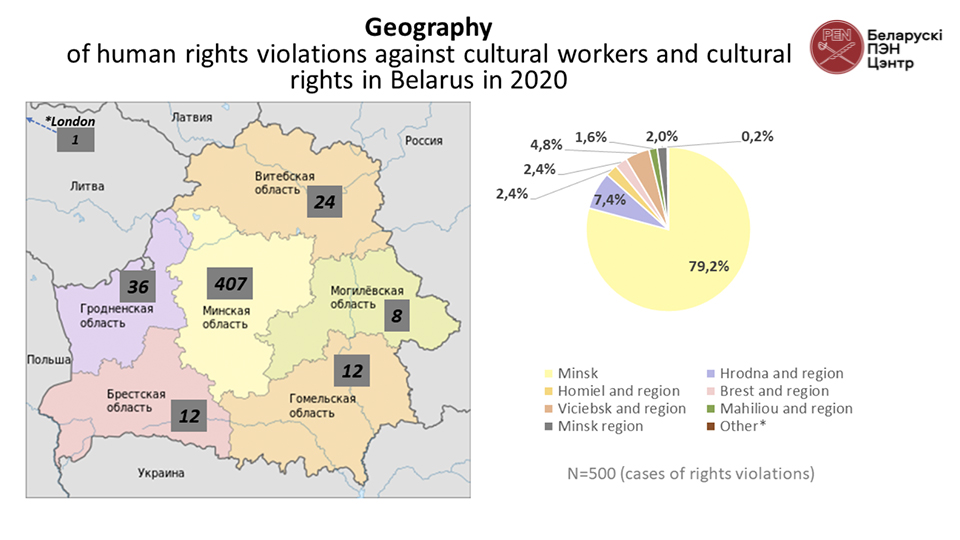

Geography of violations

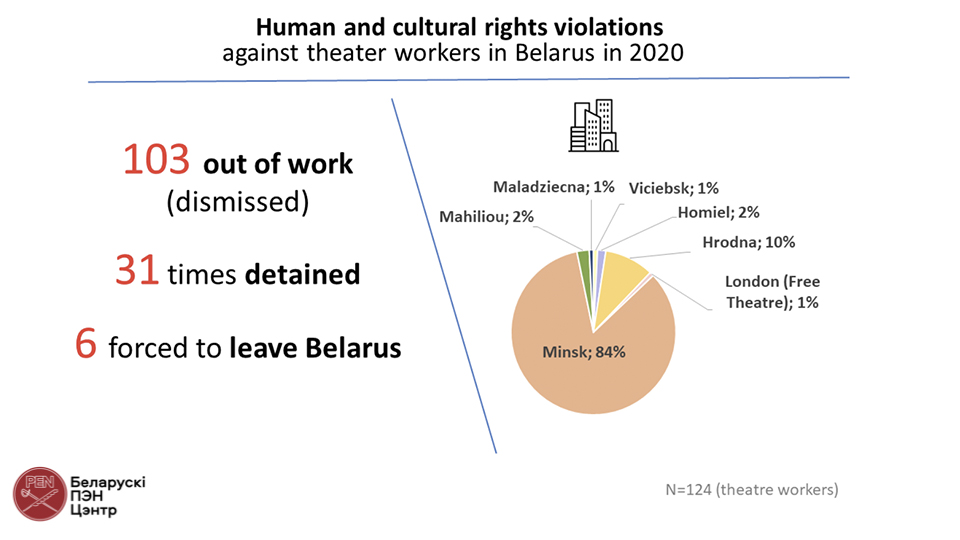

The main number of violations have occurred in the city of Minsk, followed by Hrodna and Viciebsk regions.

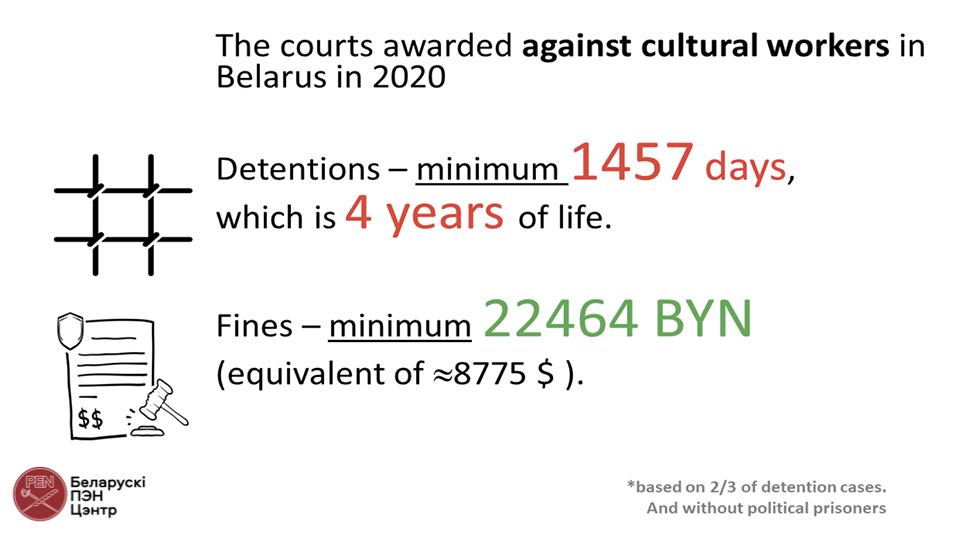

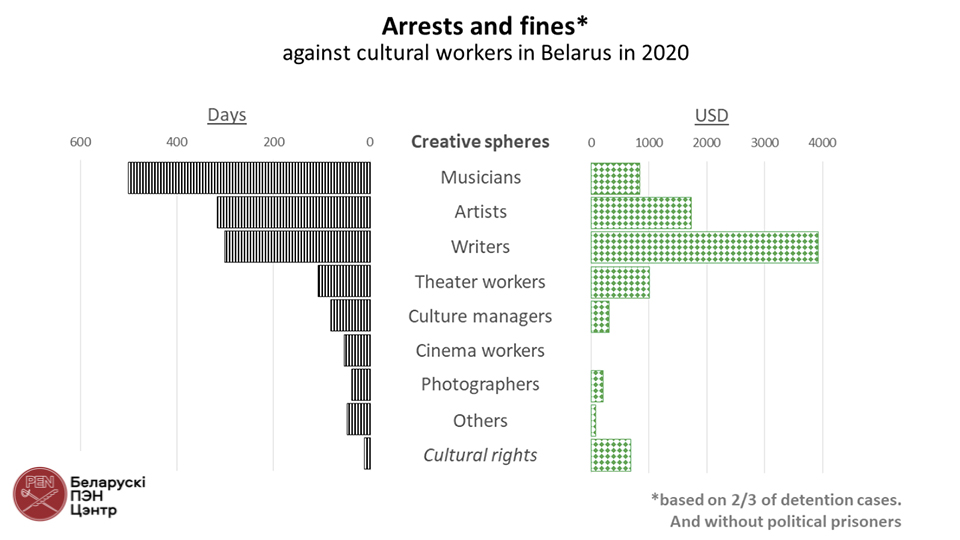

Arrests, fines, dismissals

The following is a distribution of available results by type of punishment in the context of creative groups (excluding the situation with political prisoners and without data on how at least 77 more detentions ended):

The following is a distribution of available results by type of punishment in the context of creative groups (excluding the situation with political prisoners and without data on how at least 77 more detentions ended):

According to data on 2/3 of detention cases, musicians received most days of detention, and writers received the most fines.

According to data on 2/3 of detention cases, musicians received most days of detention, and writers received the most fines.

Concerning theaters, we should note the practice of dismissal, which has no analogs in contemporary Belarus. More than one hundred people have been fired (or forced to write a resignation letter) during the period between August and December 2020.

The Belarusian PEN Center has prepared a more detailed analysis of theaters as a separate document.

The Belarusian PEN Center has prepared a more detailed analysis of theaters as a separate document.

Historical symbols

It is worth to mentioning and emphasizing that a significant number of national symbol-related violations have been documented since August and continue to the present day. This refers to countless cases of removal, cutting, trampling, and the defamation of historical symbols. During the monitoring process, more than two dozen such cases were recorded. However, since the documented cases do not convey the real scale of what is happening with the symbols, the inclusion of individual cases would only distort the real picture.

During the monitoring, we have faced cases of a “special [in terms of harshness] attitude” towards Belarusian-speaking citizens during arrests, transportation and detention. However, this tendency as well as the attitude towards symbolism requires reflection and still needs to be categorized.

Final provisions

The Belarusian independent culture has learned to exist in a parallel reality over the past 10 years, financing itself with moderate success. On the one hand, independent culture does not receive support within the country, because the state does not support independent cultural workers and independent organizations. In turn, the lack of support leads to some limitations and obstacles. On the other hand, Belarusian culture is not a priority area of support for foreign institutions, which believe that the Ministry of Culture of Belarus should manage everything. While institutions of Belarusian culture should be engaged in promotionabroad, there are simply none here. Many Belarusian cultural figures are in rather unfavorable conditions, unable to realize their creative projects, and institutions cannot fully fulfill their tasks.

Simultaneously facing a lack of financial support, cultural workers are not represented in the focus of the human rights movement in Belarus. While in several countries the implementation and protection of the rights to freedom of expression, access to culture, preservation and maintenance of national identity, religion and culture occupy an important place both in public discourse and in legal practice, the situation in Belarus is different. Rights in the field of culture for Belarus are still a poorly developed area, including in the activities of cultural organizations.

Even though cases of cultural rights violations are a fairly regular practice in our country (the systematic bans or created obstacles for concerts by Belarusian independent musical groups, the recognition of literary works and information materials as «extremist» and, as a result, the confiscations of books, approval performances before the show, etc.), they are not usually associated nor interpreted in terms of cultural rights. Instead, these violations are interpreted exclusively as political or civic issues.

Another widespread and well-known layer of cultural rights violations is associated with discrimination based on national language, as there is limited access to education and culture for Belarusian-speaking citizens. However, this situation is most often interpreted as the political, and not as a case of violation of rights in the sphere of culture.

The mentioned questions are only the most striking and systematic violations of human rights against cultural workers and cultural rights. However, even in these cases, we do not have systematized information and analysis of law enforcement practices that would allow us to draw reasonable conclusions and improve the methods of protection. In turn, it is necessary to understand that the cultural rights sphere is much broader, and it can be assumed that there are many more problems in it.

To determine how large-scale these violations are and how they become possible, we need a mechanism for the widest possible tracking of cases of violation of rights in the field of culture, and an analysis and systematization of the legal, procedural, and substantive aspects of these violations. In turn, based on research data, it’s possible to:

- reasonably estimate the situation with respect to the human rights of cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus;

- develop specific recommendations for those who face a cultural rights violation, as well as for human rights organizations and state institutions that provide legal regulation in culture.

The Belarusian PEN Center is an organization that works at the intersection of culture and human rights protection. Over the past three years, the center has been actively trying to strengthen the human rights component of its activities. PEN has taken up the challenge to monitor the implementation of cultural rights and to more actively protect the human rights and interests of target groups within the country. It is both a resource to influence the law enforcement practice and legislation in Belarus in the field of culture and to increase the possibility of interaction with partners to make culture a priority in various national and international programs.

Starting a systematic study of violations against cultural workers and cultural rights in Belarus, the Belarusian PEN Center assumed that the first few years of monitoring would provide an opportunity to calmly look and understand what constitutes the main problems in the implementation of cultural rights. However, the specific political situation of 2020 resulted in monitoring that, after a year of research, reflected widespread violations of civil and political human rights.

- An analysis of all documented [593] cases showed that 80% of violations affect civil and political rights, while directly cultural rights are violated within 10%.

- 169 people have been recognized as political prisoners in Belarus as of 10.01.2021. 15 of them are representatives of the cultural sphere and are still in jail.

- It is clear that we are dealing with a different type of reality now. We must be fully aware of that and react accordingly.

- The initial launch of recording cases of human rights violations against cultural figures and cultural rights in Belarus was intended to include subsequent communication with the Ministry of Culture of Belarus in order to influence state culture policies, change legislation, and address restrictive law enforcement practices. Now, in a situation of protracted socio-political and legal crises, massive repressions, and a lack of elementary opportunities for interaction with the government, we need maximum efforts to protect and restore violated rights, protect victims, and develop both medium-term and long-term strategies.

- The improvement of cooperation between independent organizations in the field of culture, mutual support, and the exchange of information are acquiring additional relevance.

- The analysis of violations and vulnerable areas of cultural rights, problems and gaps in legislation cannot be done at the current time due to the “distorted reality” of 2020. This is also because most of the independent cultural organizations and cultural workers are living through the current crisis time and are its subjects.

- We started recording facts confirming the disadvantaged position of independent cultural workers and non-governmental cultural organizations, the frequency of threats to creative self-realization in the state cultural sector in Belarus, and the character of discrimination based on language (Belarusian language).