This interview is part of the Voice of the Freedom Generation collection, which is a living testimony to the creative and civic presence of individuals who maintained their voice, even in exile. It shares the stories of laureates who have won the Voice of the Freedom Generation Award. This award is presented by PEN Belarus in partnership with the Viasna Human Rights Center, the Belarusian Association of Journalists, the Press Club Belarus, and the Free Press for Eastern Europe Foundation.

The collection will be presented on November 15, 2025, at 5pm during a discussion with the laureates of the Voice of the Freedom Generation Award at the European Solidarity Center (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności, Gdańsk, pl. Solidarności 1).

In the village, Belarusian identity was accepted yet considered domestic and unofficial

Siarzhuk, is childhood the poetic key to language?

My parents and books. My mother introduced me to books; she worked in the school library. Life was under control. Unlike other boys, I couldn’t skip classes. I read everything I could get my hands on. One day, I stumbled upon Yanka Maur’s Polesia Rabinsons. The language struck me like an electric current. Later, at our rural school, people spoke a mixed language, almost Belarusian.

My father was something of a dissident – he wrote parodies of Khrushchev and hid them in a drawer. At night, he’d listen to secret voices on an old tube radio: Vatican Radio, Radio Liberty… As a boy, I’d eavesdrop and wonder why he did it in secret. I understood later: Belarus had to be protected.

You still seem to believe in enlightenment, the power of words, and the beauty of a simple life. Does this come from your teaching years?

After school, I didn’t know where to go. Then, fate intervened – our neighbor’s daughter enrolled in the history department at the university in Homieĺ and invited me to join her. During the entrance exams, I spoke only Belarusian. It went smoothly.

And was school a place of growth or escape back then?

Honestly, both. In Dabrahošča, a village in the Žlobin district, where I was assigned to teach, I made lessons come alive. I brought albums, books, and games to encourage real interaction. And it worked: the children began speaking Belarusian even on the streets. Seeing them embrace the language as their own, not as something forced upon them, inspired me.

Did anyone in the teachers’ room speak Belarusian?

Hardly anyone. Occasionally, the young physics teacher or the PE teacher would. The rest were from the city, they came to teach, and then they left. To them, being Belarusian felt provincial, though they treated it with respect. Still, I didn’t feel out of place; I just did my job.

Were the textbooks in Belarusian?

No, by the late eighties, everything was already in “the great and mighty” [Russian].

Many people remember their Russian teachers fondly, but they often complain about their Belarusian teachers. Why is that?

It’s a reflection of the society of that time. Belarusian identity was considered domestic and unofficial. Urban teachers brought a wave of Russification with them. But in my school, the living Belarusian language still survived. It wasn’t taught; it was lived.

After school, you chose journalism. How was it there?

I ended up at Homieĺskaya Praŭda (The Homieĺ Truth). Although the title was in Belarusian, but almost all the texts were in Russian. I couldn’t change anymore. The language had remained in me, like blood in my veins.

For me, language is not a weapon or a symbol, but a natural state

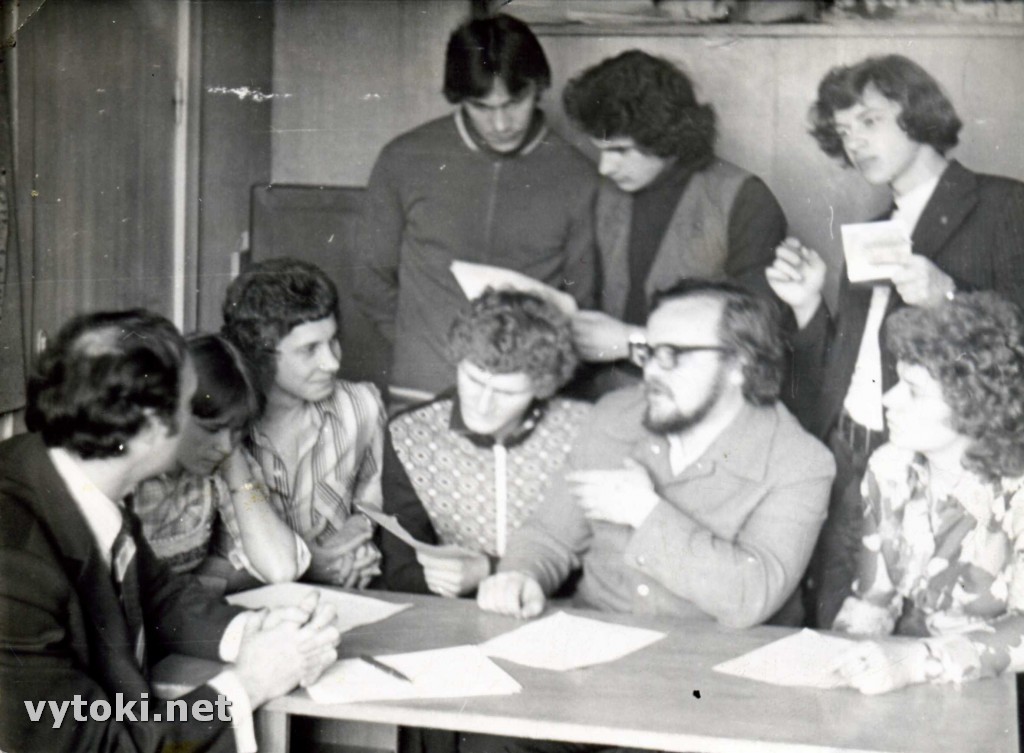

In the second half of the 1980s, you were one of the people who founded Talaka and Tuteyshyya. Were you driven by youthful energy – or by an early understanding that a nation cannot exist without its native language?

As students, we studied foreign languages, such as Polish and Bulgarian, and we were astonished to see that everything there functioned in the native tongue: newspapers, television, street signs. Here, nothing. It hurt. Yet, we had an example: Anatol Sys, a true torchbearer. He spoke only Belarusian and teased others, “What’s this, gone Russified already?” He persistently brought us back to ourselves. That was the first step toward awareness. We were not an appendage; we were a nation.

Did you feel that the country was waking up?

Yes, I remember when Minsk’s Dynamo became the USSR champion. After the decisive game, people poured into the streets, suddenly feeling like Belarusians in those happy moments. It was a kind of signal… Even a push: we, students from Homieĺ, began walking on foot across half the country, stopping in villages, looking at old churches… There it was, our land!

What were those journeys like? How did you choose your routes? What did you bring? How did people react?

When we heard about an interesting village, we’d say, “Yes, let’s go there for songs!” We’d go with a big tape recorder to see some elderly singer. At first, she’d refuse, then call her neighbors for support. We’d sit in the house, and then the magic would begin… If the words slipped their minds, we’d laugh together, and they’d remember again. It was like opening a spring.

The language there was alive, with a touch of Ukrainian coloring, yet still ours –flavorful, sharp, and precise. We compiled handwritten dictionaries, collecting the essence that nourished our poetry.

Although I had been writing poetry since school, after those lessons my poetry took on a natural breath rather than simply artificial ventilation of the lungs. Folklore and the living language made my poetry more mature. A true lesson from the people!

Was your involvement in creating the Belarusian Language Society a conscious decision?

The organizers knew I wasn’t just a village teacher who wrote in Belarusian, but also an active participant in cultural life. They invited me to Minsk. There, I met Ales Bialiatski and others who truly cared, and I immediately felt like I was part of a movement. This continued later in various ways: projects with the Union of Belarusian Writers, organizing the Anatol Sys Poetry Festival in Charoškava, and participating in PEN Belarus activities, such as serving as a jury member for the “Book of the Year” award and in events like “You Can’t Kill: The Death Penalty and Belarusian Literature.” Everything was grounded in Belarusian culture – and felt entirely natural.

Initially, the language was a sign of belonging; later, it became a tool of resistance. What is it now?

A way of being yourself. Not a weapon, not a symbol, but a natural state. When a family speaks Belarusian and their children speak it too, that’s life. I never thought it could be any other way.

You mentioned finding Belarusian words even among the Lithuanians, where you live now.

We share a common history. There are so many similarities, like the words ‘dziakuy’ (thank you), ‘vaviorka’ (squirrel). Language doesn’t divide; it connects.

School lessons are one thing, but is it easy to speak Belarusian in everyday life or in public? Especially at first?

It required a lot of courage. Sometimes it felt like a game: a test of myself and my nerves. For example, when I was in the army, I was surrounded by Azerbaijanis, Ukrainians, and Estonians. Everyone spoke differently, but Belarusian was seen as strange. When I spoke Belarusian while on guard duty, the officers would immediately say, “That’s not the language of service!” Soviet chauvinism worked flawlessly.

But even then, I did not fall silent. I had Belarusian books and magazines, such as Maladostsʹ (Youth) and Polymia (The Flame), among others. They were sent to me in large parcels from home. My friends and I read them and passed them around. When we left the army, we left behind a small library so that new Belarusian recruits would have something to read. That was our struggle as soldiers.

Your small homeland is Prakiseĺ, later Zaspa on the Dnieper bluff – a place where the land, water, and people are inseparable. Did the Polesian landscape influence your worldview and poetry?

Those landscapes are in my blood. In the spring, the great, full-flowing Dnieper would flood right up to the houses. It was the world of reflections, horizons, and vastness that cannot be forgotten.

Not only by me. Along the riverbank lived the poet Viktar Yarats, as well as Viktar Stryzhak. Across the river lived Neli Tulupava. Some time later, Nasta Kudasava appeared and made her mark. All of these people have the Dnieper in their souls. The river doesn’t just ripple and flow; it creates a way of thinking. It teaches calmness, spaciousness, and depth.

Bialiatski did not think with the emotions of revolution or a desire for revenge. Rather, he had a rational vision of the future

At one time, Ales Bialatski wrote about you. Now you are preparing a book about him. Is this a moral duty or a continuation of your friendship?

Without Ales, I would not be who I am today. We met at Homieĺ University, and during my two years in the army, he gave me a taste of freedom in Minsk. He was always my first reviewer, being very honest and uncompromising. “This is rubbish, but that’s good.” He shaped me as both a poet and as a person. How could I not repay that debt? This book is my way of thanking him. It’s about how our generation grew up.

Indeed, Bialiatski contributed greatly to Belarusian culture as a whole. His monograph “Literature and Nation” is one of the most profound works in the country. It is his true manifesto on how to view Belarus through culture and history.

Today, Ales is in Horki, you are in Vilnius, and we are scattered across the globe. Has the nation for which he went to prison appreciated his sacrifice?

Ales is a global figure, though I fear not everyone understands that. Most people can’t even imagine the extent of his influence. His activities were never confined to Belarus – he was an international advocate and the voice of his country to the world. Through him, Belarus spoke. His imprisonment is a great loss for us and the global community.

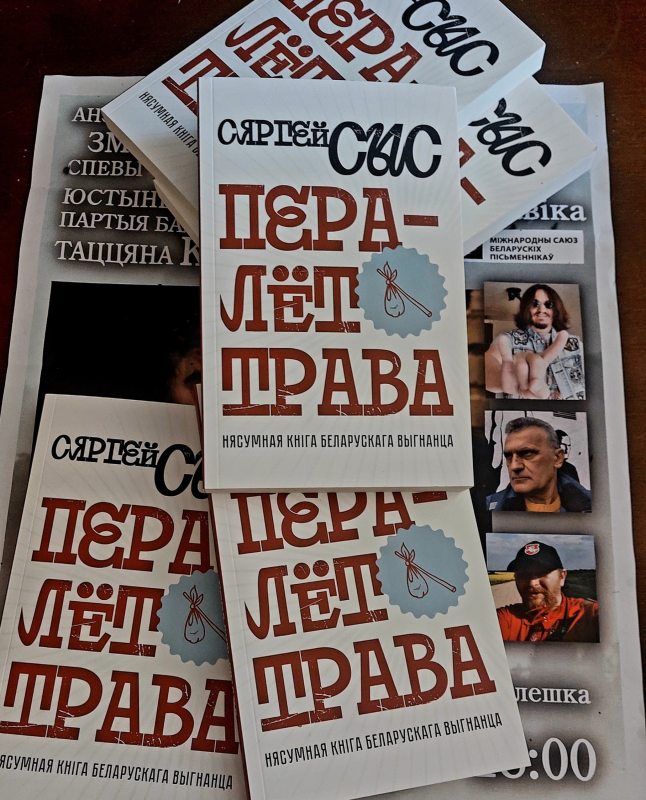

You often mention another figure alongside Ales Bialiatski – the poet and your fellow countryman, Anatol Sys. And you have a work about him, too. Is it a book of dedication?

This particular form does not claim to be objective; it’s personal. Unlike Andrei Melnikau’s monograph, which was not very successful, it is not dry. I wanted to capture a man who was not only a poet, but also a living force of nature. Although I have written a lot about him at different times, yet I always feel like I have not said everything.

Some people say he was a genius, but a broken man. Was alcohol in his blood and in his life?

During his university years, Anatol Sys was a completely different person. He didn’t drink and could talk about literature for hours. When we’d head to a bar, he’d say, “Fools! Better take a book!” Then came the army and work at the newspaper, where everything was strict and disciplined. But when he moved to Minsk and became famous, something inside him broke.

Anatol couldn’t overcome himself and remained captive to his own myth. Yet he was humble and deeply human. When he came to our village, he called my mother “my second mom.” He always stayed down to earth, no matter the legend that grew around him.

When you look back at your generation today – the boys and girls who walked beside you – how do their paths and deeds appear from today’s perspective? Idealists or political realists?

People were different, but most were idealists. They believed in the power of culture and the magic of acting without authority. Everyone was doing something; no one stood aside. Some wrote, while others simply brought planks to help rebuild a church. We are proud that the first Talaka appeared in Homieĺ, not Minsk. Our city became the place where it all began. A lot of people contributed to the start, including those who are now well-known and those who are rarely mentioned: Siahei Dubavets, Tatsiana Sapach, my former friends from Homieĺ – they were all there.

Were Soviet habits still holding things back, or had the old brakes already begun to smoke?

It was Gorbachev’s thaw; the machine started to skid. Together, we cleaned up abandoned churches and restored monuments. Not by permission or order – we just wanted to restore what was falling apart. In Valataŭ, climbers had been destroying the frescoes of an old church. We came and cleaned up the place and put up a sign. We dealt with something real. There was nothing loud or political about it; it was simply our need to breathe our language and be people of our land.

We met almost every day. “I’ll stop by after work. We’ll have coffee and talk about what’s next.” That was life. We were naive, young, and had our heads in the clouds. Dubavets would say, “I’ll quit my job and live off my creativity.” He really did, but it only lasted three months until an empty kitchen reminded him that he had nothing to feed his family. Still, it was a generation that wanted to be pure.

You grew older but never blended into everyday life. On the contrary, you became the foundation of civil society that still holds Belarus together today.

Absolutely right: ordinary young people grew into influential figures and propelled the young country forward. Their ideas helped awaken others. We were just a few back then, but now there are hundreds. I remember our gatherings in Kušliany at Bahushevich’s house. We came from different cities, but we were already a team. Team spirit, team words. It wasn’t just a celebration; it was a school of patriotism. There, we learned to be Belarusians not by decree, but by blood and by heart.

Today, you build your home piece by piece, like a construction set, out of friendship, memory, and hope

You have a book of poetry titled DOM. What does “home” mean to you today – a place, a language, or people?

Home is where it feels cozy and safe. It’s where friends are nearby and you can breathe freely. That’s the essence of it, though this word carries many meanings in different languages: from “prison” to “gift.” And they’re all true! When you don’t have a physical home, you build one from what you have: friendship, memory, and hope. Piece by piece like a construction set. It becomes your place, even if it’s constantly moving with you.

Ukraine: Lviv, Chernihiv, Zhytomyr, and Kherson are the cities where you lived and performed. What did the lessons of peace, war, and freedom mean to you?

Ukraine gave me a second wind. There, I saw free people without boundaries, fear, or coercion. Creativity, language, and life itself were natural and light. After Russia, I came to that world, and it felt as if one could become intoxicated by freedom. In Russia, I was hiding – without a passport, under surveillance, and writing at night like an underground author. My poems were dark and heavy with despair. But in Ukraine, it was the opposite. Heaven and earth. There, I wanted to write. Not only did I want to write about myself, but also about my homeland, its culture, and its spirit.

In Lviv, I performed for three hours. People were listening not so much to the poetry as to Belarus. They wanted to know who we were and what was happening to us. They understood that poetry could serve as a form of testimony. Yet, many of the people sitting in the front row are no longer alive—young, talented individuals who died in the war. I remember their faces and realize that the best among us sacrifice their lives for freedom. For me, that is the lesson: to give myself now to Belarus, to people, and to life.

And yet, Ukrainians often joke that our 2020 looked like an innocent scene with balloons, benches, and flowers. How did you fend off that kind of stereotypical nonsense?

Every nation walks its own path to freedom. We differ in our methods of resistance. But we are all the same in our human dignity. Those who mock us simply don’t know. They don’t understand their neighbors’ history, how things really were, or what our struggle cost us. But that’s by no means a common attitude. Ukrainian intellectuals and cultural figures genuinely warmly treat Belarusians. When I lived in Chernihiv, I would often hear: “Our Belarusian is coming.” Not “the one from Belarus” or “their guy,” but ours. It was very moving.

Before the war, life in Ukraine must have meant expanding your circle of friends, especially if you were open to communication. Are those warm relationships still alive now?

Back then, I participated in many festivals and performed in Zhytomyr, Lutsk, and Lviv. It gave me a feeling of home.

Now, when the world is so quick to divide people into “us” and “them,” I’ve had a strange experience. I translated poems by five Lutsk poets who had been my friends for years. I wanted to publish them in a Belarusian journal. I reached out to the head of the regional writers’ union: “Please send me short bios and photos of the authors.” He replied, “This one will agree, but she won’t for any money. Don’t approach those two; they’re angry at you Belarusians.”

What do you do when there’s so much resentment, yet your work depends on trust?

I reached out to each of them personally. After all, they know me as a person. Still, some refused. “We respect you, but we don’t want our poems published in Belarusian. You are our enemies now.”

That hurts. But I don’t hold a grudge; I live with it. They and we are people who have experienced pain and are still searching for home.

After all these journeys and tribulations, what remains most important?

We lived, we live, and we will live. We worked, and we will continue to work. We were dignified, and we will remain so. Belarusians have a great history, and we will not lose it. Here in Vilnius, I see children studying in Lithuanian schools yet singing in Belarusian, organizing events, and gathering together. They haven’t experienced the crackdowns or been imprisoned, yet Belarus lives inside them. They are sprouts: young, resilient, and unbreakable. I believe their time will come. I try to do everything I can to make that happen sooner. Otherwise, what’s the point?

The full version of the interview is published in the Voice of the Freedom Generation collection.

The Voice of the Freedom Generation project is co-financed within the framework of the Polish Cooperation for Development Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The publication reflects exclusively the author’s views and cannot be identified with the official position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.