Since October 2019, PEN Belarus has systematically documented the violations of cultural rights and human rights of cultural workers. This monitoring report contains statistics and analyses of violations in the field of culture in January–June 2023. It summarises information collected from open sources (77% of cases), through personal contacts (11%) and in direct communication with cultural figures in the framework of the research project [1] on hidden repression (11%).

NB: For users’ information security, we do not provide direct links to information sources if they are subject to restrictions under the current regulations in the Republic of Belarus. More on the monitoring.

Main results of the monitoring

Human rights violations against cultural figures

Criminal prosecution

Administrative prosecution

Dismissals

Other forms of persecution

Administrative obstacles to cultural activities. Censorship and “blacklists” of cultural figures

Addition to the list of cultural “extremist materials”

Public policy issues in the cultural sphere

MAIN RESULTS OF THE MONITORING

Politically motivated persecution of cultural figures in the first half of 2023 was mainly in connection with the 2020 events in Belarus. Targeted were those who participated in peaceful protests, endorsed collective appeals from professional communities to the state authorities to stop violence against citizens, donated to violence victims’ relief funds, left reactions on social media under high-profile publications and carried out other actions at the time. Subject to prosecution also was subscription or distribution of “extremist materials” and dissent, in general.

Interrogations and searches, detentions and administrative arrests of cultural figures, criminal prosecutions, pressure on prisoners in correctional institutions, and inclusion in state-approved lists of “extremists” and “terrorists” continued unabated. There were both targeted and mass dismissals of undesirable employees. Professionals from various cultural sectors found themselves on “blacklists.” There is a de facto ban on the profession for representatives of the independent cultural sector and those who worked in state-run cultural and educational institutions but were deemed disloyal to the regime. Cultural figures are forced to leave the country, some facing the ‘leave or go to prison’ choice. Those who remain in Belarus continue their work (“…people are just afraid if I am honest. But we are doing something, you know?” (© )) [2] and, realising a new reality, resort to self-censorship and anonymity. The independent culture lives in a “silence mode” (“…now the silence is our main asset” (©)) and is in search of other ways of creative expression and self-realisation.

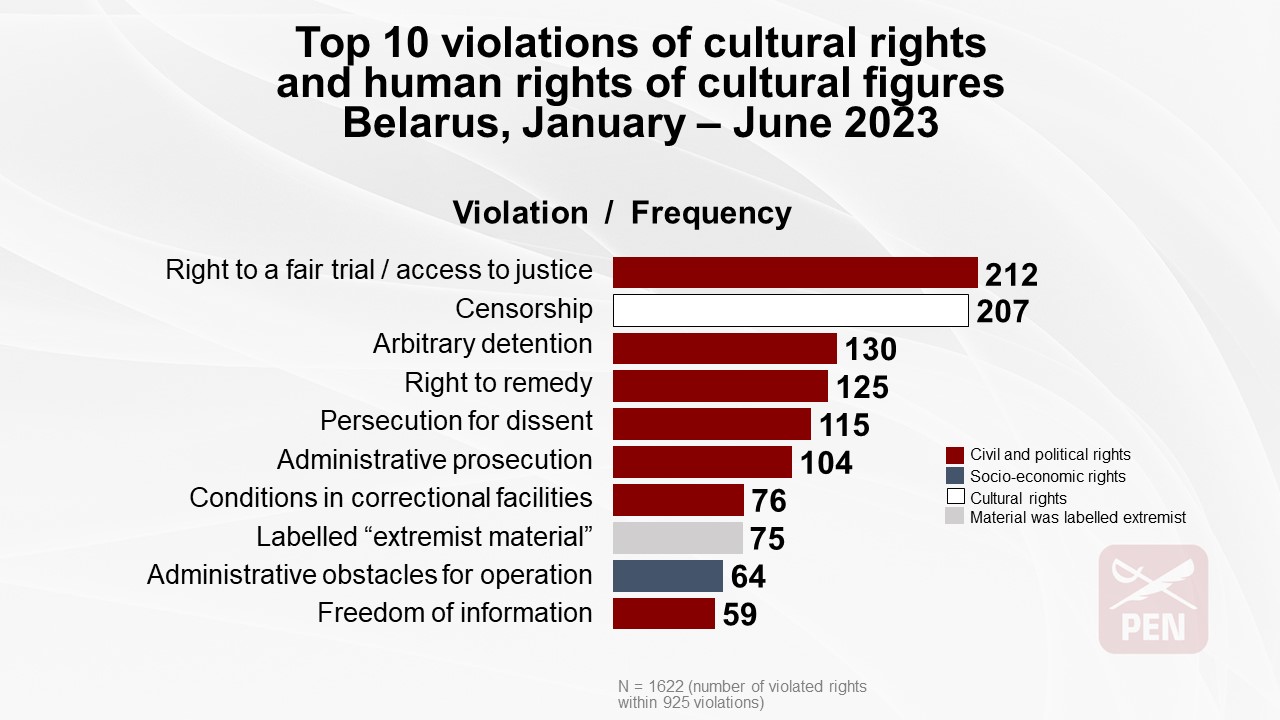

- In January–June 2023, there were 925 violations of cultural rights and human rights violations against cultural workers in Belarus.

- The infringement on the right to a fair trial/access to justice and censorship are the prevailing violations against cultural figures in the monitored period.

- The following cultural figures died behind bars: artist Ruslan Karčauli (in a Hrodna prison), cultural manager and blogger Mikalai Klimovič (in a Viciebsk penal colony), artist and performer Aleś Puškin (in a Hrodna prison). Human rights activists and members of the public attribute these tragic deaths to the conditions of detention and inadequate medical care in closed institutions of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MIA). The poet Dzmitry Sarokin died under unclear circumstances at the Lida District police station.

- As of 1 July, no less than [3] 133 cultural figures were in penal colonies, prisons, pre-trial detention centres (SIZOs), open-type correctional facilities or home confinement [4]. Human rights defenders recognised 114 of them as political prisoners.

- At least 15 people have remained in detention for over 1,000 days or almost three years. Cultural workers persecuted for political reasons are subjected to cruel treatment, constant restrictions and pressure. Their communication with the outside world is either absent or significantly restricted.

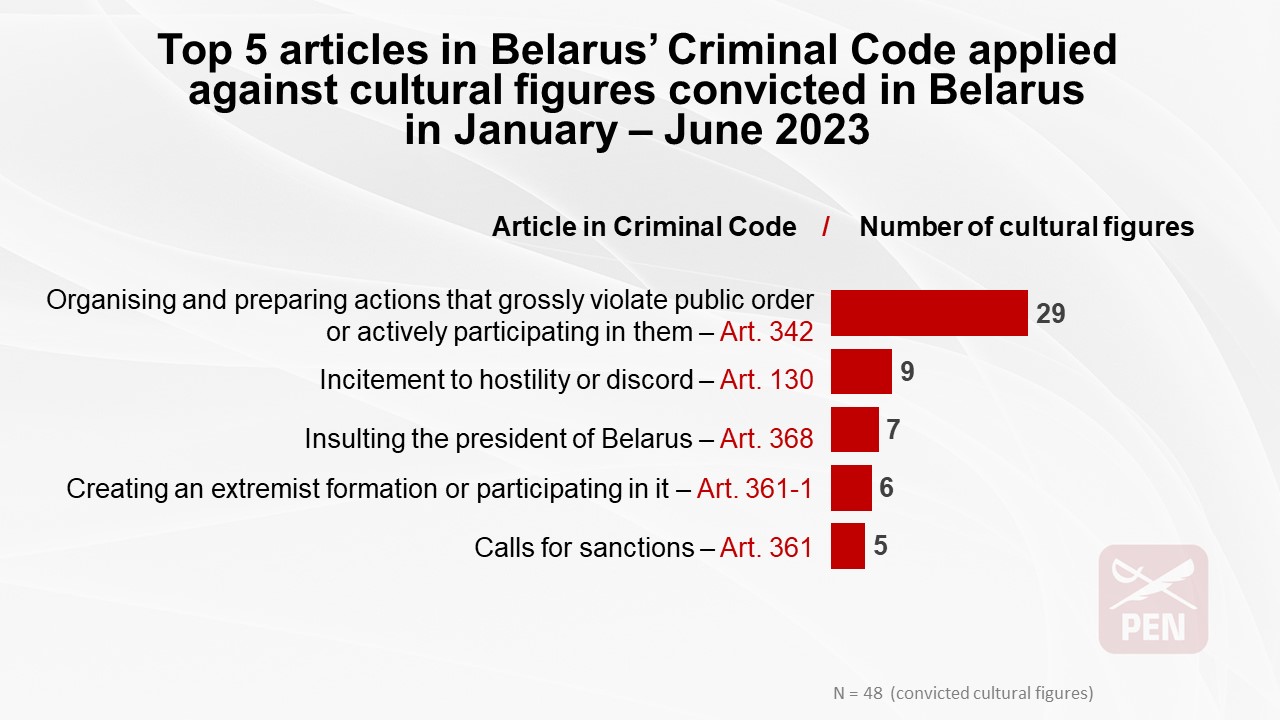

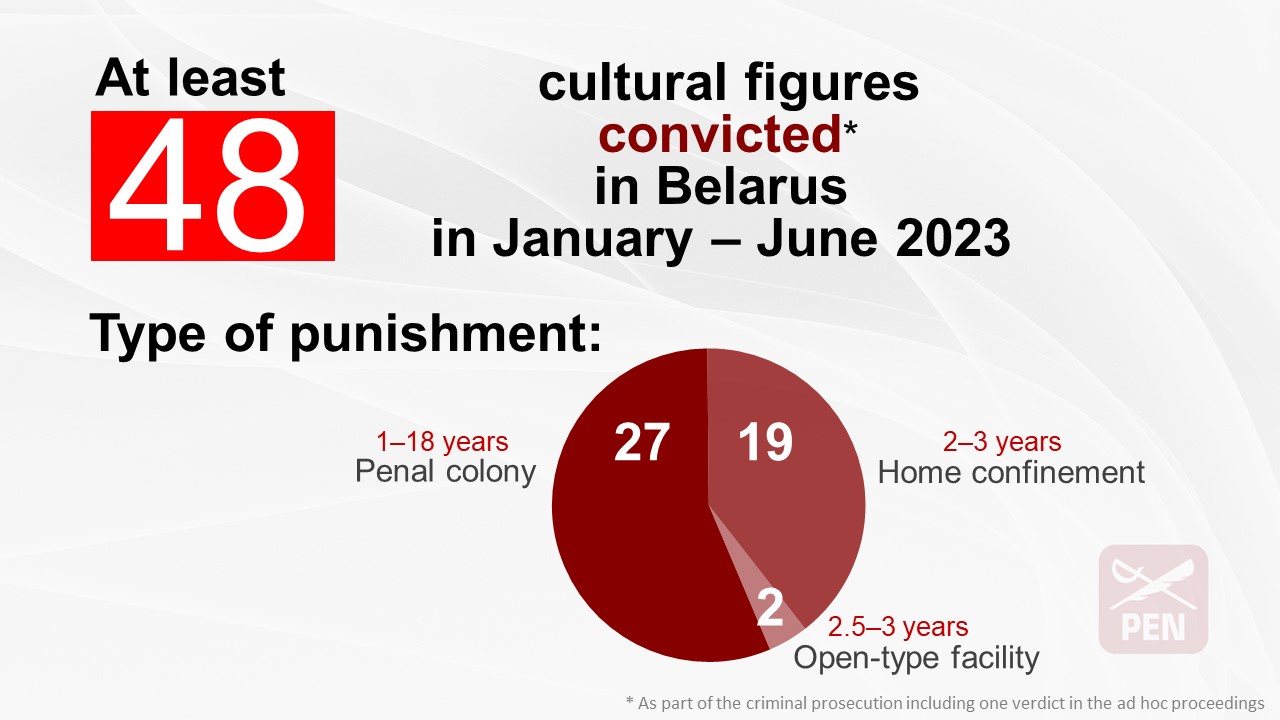

- At least 48 cultural figures were convicted. In most cases, their criminal prosecution was based on charges under Article 342 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus (“Organising and preparing actions that grossly violate public order or actively participating in them”) – for participating in peaceful rallies and protests. At least 212 people have been convicted since the end of 2020.

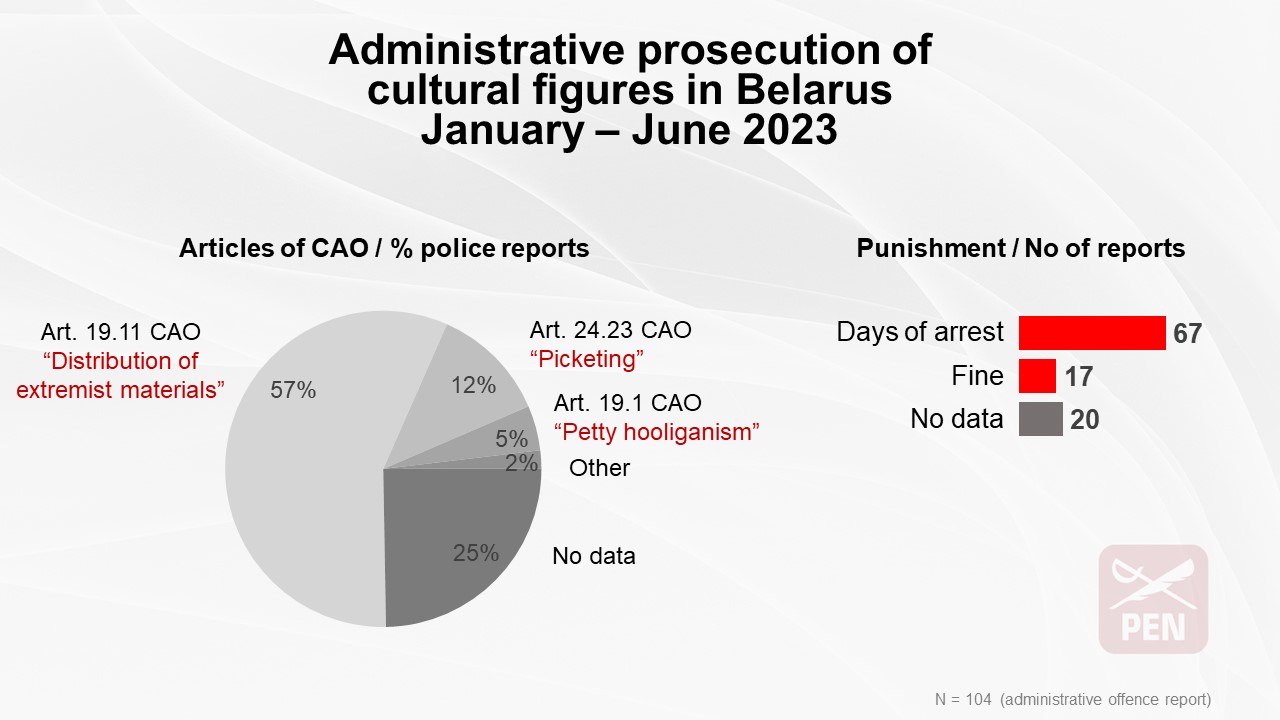

- During this half of the year, monitors recorded 130 cases of arbitrary detention of cultural figures and 104 administrative prosecutions. At least one in two police reports was drawn up under Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Distribution, manufacture, storage, transportation of information products containing calls for extremist activity or promoting such activity”) – for subscribing to or reposting publications on the Internet.

- Cultural workers are summoned for interrogation, searched at border crossings, made to record “penitential” videos, pressurised through relatives, fired from state-run cultural and educational institutions, expelled from creative unions (e.g. the Union of Artists), etc.

- Crackdown on dissent and freedom of expression takes place under the guise of combating extremism and terrorism:

-

- The Ministry of Internal Affairs included 153 cultural figures in the “List of citizens of the Republic of Belarus, foreign citizens and stateless persons involved in extremist activities”; 23 people are on the State Security Committee (KGB)’s “List of organisations and individuals involved in terrorist activities”. 20 persons are on both lists. Inclusion in the lists entails additional rights restrictions.

- The music group Tor Band, the non-governmental organization “Belarusian Association of Journalists”, the regional media outlets Homiel Štodzień (Homiel Daily) and MOST (they cover, among other things, the topics of the Belarusian language, historical and cultural identity) were designated by the KGB as “extremist formations”.

- At least 75 culture-related materials (including social media accounts run by cultural figures) were labelled “extremist” by the Ministry of Information. The list includes 18 books, 12 issues of the Our History and ARCHE magazines, Telegram channels dedicated to Belarusian history and language: Historyja, Belarus history, Belaruski Babilon, Tolki pra movu (About language only), cultural and educational portal Budzma belarusami! (Let’s be Belarusians!), the printed version of Rehijanalnaja Hazieta newspaper, several videos or songs by Dai darohu!, Sumarok, Deti Khrushchevok, faceOFF, the YouTube channel Tyapin CREW, the Ukrainian song “Ah, Bandero!” and some others.

- Administrative obstacles, censorship and blocklists are the primary mechanisms for state authorities to pressure the cultural sector.

-

- Repressions against the non-state book-publishing sector are in full swing. During the monitoring period, three publishing houses – Januškievič, Knihazbor and Zmicier Kolas – officially stopped their work in Belarus. The government set up regulatory obstacles for distributing Belarusian books inside the country and for their export abroad.

- Another 21 culture-related non-profit organisations were liquidated by force. At least 204 non-profits have been subjected to this procedure since the beginning of the targeted crackdown on civil society in Belarus at the end of 2020.

- There are “blacklists” of politically “unreliable” writers, artists, photographers, actors, musicians, tour guides, and museum workers.

- The state deliberately creates administrative obstacles to concerts, exhibitions, meetings, hobby clubs and other cultural events. It controls theatre repertoires, film distribution, museum expositions, etc.

- There are cases when the participants of cultural events were persecuted. For example, in January, police detained the participants of a sightseeing group travelling to the rite “Kaljadnyja Cary” (Three Kings), included in the UNESCO list of intangible heritage. In June, law enforcement agents raided the territory of the Stuly manor house agricultural centre when spectators had come to watch Batlejka – an amateur puppet theatre show.

- The state continues to persecute its citizens for public manifestations of being Belarusian (language, symbols, publications on national history), supporting Ukraine and condemning Russian military aggression there. It speaks the language of hostility to the population, sows hatred, Russifies the sphere of culture, and increasingly strengthens control over it.

HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AGAINST CULTURAL FIGURES

- Deaths of cultural figures in prison, criminal prosecution, court verdicts, conditions of imprisonment

The year 2023 brought the deaths of several imprisoned cultural figures. On 5 January, artist Ruslan Karčauli died in a Hrodna prison. According to the information received, the death occurred after suffering from pneumonia due to untimely medical care. On 6 May, cultural manager and blogger Mikalaj Klimovič, a 61-year-old political prisoner with a Class 2 heart disability, died in a Viciebsk colony. On 28 February, he was sentenced to one year in a penal colony for posting the “Funny” reaction under a satirical image of Lukašenka on Odnoklassniki social network. On 1 June, 37-year-old poet Dzmitry Sarokin died under unclear circumstances in the Lida District’s police station – the details of the incident are yet to be known. On the night of 11 July [5], political prisoner artist and a human legend of performance art Aleś Puškin died in intensive care while his five-year prison term for his 2014 portrait of the anti-Soviet partisan Jaŭhien Žychar. To date, there is no official information about the causes and circumstances of the death of Aleś Puškin, who was serving his sentence in a Hrodna prison. However, the news that has come to light testifies to a neglected ulcer perforation and untimely provision of the necessary medical care to the artist.

As of 1 July 2023, at least 133 cultural figures were under criminal prosecution in penal colonies, prisons, pre-trial detention centres, open-type correctional institutions or home confinement, including 114 recognised as political prisoners. According to the Human Rights Centre “Viasna”, there are 1,496 political prisoners in Belarus. The initiative to support political prisoners DISSIDENTBY puts the number at 1,750.

At least 15 people have remained in detention for more than 1,000 days (almost three years, namely: cultural manager, video blogger and politician Siarhiej Cichanoŭski; writer, civic and political activist Paval Sieviaryniec; philanthropist and politician Viktar Babaryka; cultural manager Eduard Babaryka; musician and activist Siarhiej Sparyš; dancers Ihar Jarmolaŭ and Mikalaj Sasieŭ; author of prison literature, anarchist Aliaksandr Franckievič; musician and cultural project manager, civic activist Maryja Kalesnikava; writer, bard and lawyer Maksim Znak; documentary film director and blogger Paval Spiryn; UX/UI designer Dzmitry Kubaraŭ; architect Arciom Takarčuk; history promoter, blogger Eduard Palčys; designer, architect Rascislaŭ Stefanovič.

Cultural workers persecuted on political grounds are subjected to inhuman treatment in detention, constant restrictions, and pressure. They remain incommunicado with their families and lawyers. Their relatives often do not hear from them for months. For example, no independent information about Siarhiej Cichanoŭski has existed since March. Correspondence with Maryja Kalesnikava and Maksim Znak was interrupted in April. There is still no communication and information about the state of health of Viktar Babaryka after his hospitalisation in a severe condition in late April. The penitentiary system did not explain what happened to him. Cultural figures behind bars face additional pressure throughout their imprisonment term. One of the respondents in the research on hidden repression described it as a “prison within a prison“: “…sitting in a [penal] colony, he [Uladzimir Mackievič] gets forbidden: people around him are not allowed to talk to him. If people around him talk to him, they get into punitive confinement… He is forbidden to receive parcels or letters. It’s terrible – there are repressive methods in addition to the criminal punishment.”

No less than 48 cultural figures were convicted in Belarus during the first half of the year, including the first verdict issued in the ad hoc proceedings – the trial in absentia of Paval Latuška, ex-culture minister of the Republic of Belarus, former director of the Janka Kupala National Drama Theatre, a politician. The charges for cultural figures were based on between one and seven articles of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus. In most cases, the prosecution relied on Article 342 (“Organising and preparing actions that grossly violate public order or actively participating in them”) for participating in peaceful rallies and protests in 2020.

27 cultural figures were sentenced to imprisonment in penal colonies, 19 to home confinement and 2 to a term in an open-type correctional facility.

Paval Belavus, a prominent populariser of Belarusian culture, cultural manager, the founder of the independent cultural platform Art Siadziba in Minsk in late 2011 and the shop of national symbols Symbal.by in 2014, was sentenced to 13 years in a medium-security penal colony. The regime charged Paval Belavus with “state treason,” “harming national security”, and “spreading the ideas of Belarusian nationalism” for his Belarus-minded stance and promoting Belarusian national identity through concerts, literary meetings, lectures, and popularisation of Belarusian traditional symbols. “This is the most eloquent example of recent weeks,” one of the respondents told us in an interview, “as this man was not engaged in any political activity. He is a purely cultural figure, talented, active and capable… He received such a long term. The charges’ wording is reminiscent of Stalin’s times because, in my opinion, no one has ever been imprisoned with the wording “Belarusian nationalism” before him… Obviously, this is a typical politically motivated verdict…“.

Courts issued terrible sentences for human rights activist, writer, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aleś Bialiacki (10 years in a medium-security penal colony and a 185,000 BYN (~63,000 USD) fine for his human rights work and assistance to the victims of repression); publicist, political scientist and researcher Valeryja Kasciuhova (10 years in prison for her professional activities); musician Jaŭhien Gluškoŭ (9 years in a medium-security penal colony for a photo of the military airfield in the village of Ziabroŭka, Homiel region, from where Russian force launched missiles on the territory of Ukraine); journalist, essayist, member of the Union of Poles of Belarus Andrzej Poczobut (8 years in a medium-security penal colony for expressing his opinion on the Belarusian protests of 2020, historical facts of 1939, defence of the Polish minority). Ruslan Labanok, the founder of the Spanish visa centre, and Vaclaŭ Areška, a cultural critic, archivist, and activist of the independent trade union “REP”, were sentenced to 11 and 8 years in a medium-security penal colony, respectively.

At least 212 cultural figures have been convicted since November 2020.

Arbitrary detentions of people, including those with creative jobs, continue in Belarus. In January-June 2023, tour guides and musicians, cultural managers and humanities teachers, artists and writers, photographers and museum workers, dancers and artisans were detained. There were also mass detentions: employees of the Polack National Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve (end of March), TV and Radio Company “Homiel” (early May), Viciebk State Technological University (mid-May), Polack State University (second half of May).

In the first six months of 2023, we recorded 130 cases of arbitrary detention of cultural figures. At least 88 detainees faced administrative proceedings and, in some cases, criminal prosecution. Several people were released after some time, and information on other detentions is incomplete. The monitors collected information about 104 administrative proceedings against cultural figures during the study period. In rare cases, detention did not precede the trials – it could be a second police report or administrative prosecution against those already serving a criminal sentence. At least one in two police reports on administrative offence was drawn up for subscribing to or reposting publications designated by the regime as “extremist” under Article 19.11 of the Code of Administrative Offences (“Distribution, manufacture, storage, transportation of information products containing calls for extremist activity or propaganda of such activity”). The most common type of punishment was administrative arrest (at least 2/3 of cases). No less than 861 days (almost 2.5 years) and 18,798 BYN (~5600 €) in fines were awarded to cultural figures in administrative trials in the monitoring period.

After spending days in unsanitary conditions, overcrowded cells and under constant pressure from the staff of detention centres, people are obliged to cover the “costs of their detention” in the CIO (Centre for the Isolation of Offenders) or TDC (Temporary Detention Centre). 15 days of arrest cost 277.5 BYN (~82 €). Cultural workers who worked in a state-run institution were, in most cases (if not all), dismissed after serving administrative arrests.

“Unreliable” people continue to get fired in Belarus. In the first six months of 2023, the monitors collected facts about the dismissals of 48 cultural workers. We learnt about them from open sources and when researching hidden repressions. We are trying to seek and gather information about this type of repression. Still, we are aware that the facts in this section do not reflect the complete picture of dismissals from the cultural sector, primarily because many people are reluctant to voice this information even under conditions of confidentiality. (“I don’t want to give their names”, “I can’t say”, “I’d rather not give her surname” (©), etc. Loyalty checks are routine in state-run cultural institutions. Those who do not meet ideological standards find themselves under pressure, fired or in conditions where dismissal is imminent. In 2023, firings (formalised as “contract termination by mutual agreement of the parties” in many cases) or non-renewals of job contracts occurred following an employee’s detention (“…a note from the police that they detained me… I mean it was just a couple of hours, not even 24 hours” (©)), administrative arrest or criminal prosecution – technically “for absenteeism”. Dismissals could also be caused by a signature for the nomination of Viktar Babaryka as a presidential candidate in the summer of 2020 (“Just some list arrives, and that’s it, you are on it – and that’s it” (©)); “…delations written in connection with professional activities“; donations (“…donated to ‘extremist’ funds” (©)); defamatory publications against cultural figures in pro-government media, online news channels and social media accounts of activists.

Dismissal from state-run institutions for these reasons entails problems for a person in subsequent employment. It means that the road to any state-funded organisation in Belarus is closed. “They fired him/her and made it clear that ‘you will not get a job anywhere else'” (©). There were some cases when a specialist managed to find a job in another state-run organisation. However, it was a rare exception to the rule.

During the monitoring period, dismissals of disloyal specialists (“…..who are inconvenient” (©)) took place in the Zair Azgur Memorial Workshop Museum, the Polack National Historical and Cultural Museum-Reserve, the Jakub Kolas Institute of Linguistics, the Institute of Philosophy of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, the Polack and Belarusian State Universities, the Lyceum of the Belarusian State University, the Belarusian State Puppet Theatre, Homiel City Youth Theatre and several other cultural and educational institutions. Since 2020, we have recorded 376 cases of dismissal for political reasons.

Cultural workers are subjected to searches and interrogations at the KGB, the Main Directorate against Organised Crime and Corruption (GUPOBiK), local police stations and other law enforcement units. They are invited “for a chat” at the prosecutor’s office. Visits of law enforcers to relatives, threats, compulsion to record “repentance” videos and other forms of pressure and intimidation have also become widespread.

The number of summons to interrogation over online donations to solidarity funds is rising. Investigators threaten people with criminal prosecution for financing “extremist” and “terrorist” activities. They encourage them to pay an amount equal to ten times the size of the donation to the bank account of a particular institution or provide a list of several institutions to choose from “independently”. In some cases, there were attempts to recruit cultural figures as informants. They were asked to sign a document on cooperation and promised confidentiality and loyalty in return for providing information in the future.

Questioning at border checkpoints is yet another increasingly widespread practice of harassment and intimidation. All cultural figures from the database of those punished in administrative trials are repeatedly subject to thorough checks at the border posts when they return home. “…I also have 23.34, they search, customs officers, they draw up an inspection report, but I would call it a standard procedure… it has become a new reality, something ordinary…” (©). Yet, it can be very different: “…customs officers inspect you, count the money… Some man told me that he was undressed, for example. Well, this is one of those unpleasant things …” (©). Many-fold more people now go through the “conversation” and phone inspection when they travel back to Belarus. Conversations at the checkpoint can last 40 minutes or longer. “They ask you where you’ve been and why you travelled. They ask about friends, relatives abroad or particularly in Ukraine, look at subscriptions on the phone, etc. There are known cases when a person was released after a conversation, but shortly after, officers came to their home to search the house and detain the person. We are inclined to treat all these cases as violating the right to free movement. The matter requires separate research by relevant experts. One must mention the incidents with the Polish writer Maja Wolny and the former headmistress and teacher of a Polish school, activist of the Union of Poles of Belarus, Anżelika Orechwo. Maja Wolny in January was not allowed into Belarus despite the visa-free regime for Lithuania, Latvia and Poland citizens. She also received a ban for entering the country for 20 years. Anżelika Orechwo in June was not allowed to exit Belarus without explanation.

ADMINISTRATIVE OBSTACLES TO CULTURAL ACTIVITIES. CENSORSHIP AND “BLACKLISTS” OF CULTURAL FIGURES

Repressions against independent book publishing do not stop. On 10 January 2023, Minsk’s Economic Court ruled to terminate the certificate of state registration of self-employed entrepreneur Andrej Januškievič as a publisher. The Januškievič publishing house was closed. The reasoning for the decision was that Januškievič “published” printed editions, “which contain appeals to actions aimed at harming the external security of the Republic of Belarus, its sovereignty, territorial integrity, national security and defence capability, or knowingly false information, defaming the honour and dignity of the President of the Republic of Belarus, as well as containing information of extremist or pornographic nature, information promoting war, Nazi symbols or paraphernalia, the cult of violence and cruelty, or aimed at inciting racial, ethnic or religious enmity or intolerance”, namely Alhierd Bacharaevič’s novel The Dogs of Europe, a children’s book based on Joseph Brodsky’s poem A Ballad about a Small Tugboat and Sviatlana Kazlova’s scientific monography about WWII The Nazi’s Agrarian Policy in Western Belarus: Planning, Resources and Implementation (1941–1944). The Ministry of Information designated these books as “extremist materials” in 2022. The oldest private publishing house Zmicier Kolas, which had been working in Belarus since the late 1980s, was liquidated on the same pretext. On 11 April, Minsk’s Economic Court ruled to terminate the certificate of state registration of self-employed entrepreneur Dzmitry Kolas following a lawsuit filed by the Ministry of Information for publishing a collection of documents about the Polish-Belarusian borderline of 1939-1941, Liberated and Imprisoned, by Doctor of History Aliaksandr Smaliančuk. The book was designated as “extremist materials” in January 2023. “The mechanism is as follows: first they pick some book, claiming it is extremist, and then they use this pretext to close the publishing house” (©). Since 12 February this year, the Knihazbor publishing house has been in the process of liquidation. The Ministry of Information suspended its operation for several months last year. The non-state publishing houses Goliaths and Limarius were also liquidated in 2022. As a result, the books of all these publishers are withdrawn from the sales system in state bookstores, with the consequence that “… entire shelves are gone. Not just that one author or one title, the shelves are disappearing. I feel almost what I felt … in 2003 in Minsk: you go in – and there is only fiction literature from the state-owned publishing house Belarus, Belarusian Encyclopaedia… Ah, Encyclopedia is already closed. And there is nothing else… One can say that only state-funded books are present in shops” (©).

Even though the sector of non-profit organisations (NPOs) shrank significantly in Belarus in 2021-2022, forced liquidations of civil society organisations continue. “…And about organisations – well, as if they were also closed down at once practically, they started to close down from 2020, and now there are no organisations left at all”, “there are no NGOs left… at all”, “…and I think they were all closed down already in 2022, leave alone 2023…” (©). In the first six months of the year, at least 21 other NGOs in the cultural sphere stopped operations. On 10 January, the Supreme Court liquidated the oldest public organisation of Belarus – “Belarusian Voluntary Society for the Protection of History and Culture Monuments”, established in 1966. Historian-ethnologist and culturologist Anton Astapovič headed it for the last 15 years. One can hardly overestimate this organisation’s contribution to preserving historical and cultural heritage. On 28 April, Hrodna Regional Court ruled to liquidate the first officially registered Lithuanian public association, “Gimtinė” (“Homeland”). The organisation’s seat was at the Lithuanian-language secondary school in the village of Pielesa in the Hrodna region since 1993 (authorities shut down the Pielesa secondary school in August 2022). At least 204 cultural organisations have been forcibly liquidated since the targeted campaign to crack down on civil society in Belarus began in late 2020.

The state interferes in all sectors of the cultural sphere. The administrative obstacles it creates complement total censorship and a ban on freedom of expression. Just one phone call from the Ministry of Culture cancelled the offline festival of the author’s films “Unfiltered Cinema”, scheduled in Minsk on 24-26 March. Authorities employed similar tactics to disrupt the educational film lectures of the festival three times. The latest sequel of the Russian film “What Men Talk About” was removed from distribution following an order from the Ministry of Culture. The Belarusian psychological thriller “A Strange House”’s screening was cancelled right before the premiere, as the movie was to pass ” additional verification” despite its April 6 unrestricted release in Russia. The Russian-Belarusian series “Half an Hour Before Spring”, dedicated to the legendary Soviet-time Pesniary band, was released in a redacted form in Belarus. “Following a request from the Ministry of Culture, the faces of these two actors [Dzmitry Jesianievič and Hieorhi Piatrenka] were blurred” (©). The Ministry of Culture banned the cosplay festival Free Time Fest in Homiel. Jahorava Hara folk group’s jubilee concert did not occur due to the band’s forcible suspension. Ivan Kirčuk’s mono-performance at the Kupala National Drama Theatre was cancelled.

Prime Hall, the capital city’s most famous concert venue, was forced to remain closed for several months. The exhibitions of Belarusian painting “Leanid Ščamialoŭ. Dedication…” and “Exhibition of Belarusian easel and book graphics of the 20th-21st century” in the Palace of Arts, organised by the Union of Artists, were cancelled. Book presentations, lectures, and round tables were cancelled in Minsk and the regions. Plays were removed from the repertoires, touring certificates were not issued, and “unreliable” for the regime cultural figures were not allowed to participate in exhibitions, conferences, festivals, meetings and other events. “Only the “right” ones can be invited” (©). The words of Anatol Markievič, the Minister of Culture, confirm the above. At the end-of-the-year meeting of Belarus’ Ministry of Culture last February, he said, “Traitors have no place on stage, whether it is a state-sponsored high-level event or a concert in an agricultural settlement.” To strengthen the state’s role in regulating concert activities, the government has maintained a register of organisers of cultural and entertainment events since 1 August 2020. The Belarusian Philharmonic Society and other sizeable state-run concert organisations oversee the organisation of foreign performers’ tours. Proposals were put forward to set up a register of performers and other creative workers, including scriptwriters and directors [6].

Censorship in Belarus exists in two forms:

- institutionalised –

the amendments to the Code of Culture regulate the composition of participants at a cultural event, its theme, title, content, and organiser. The organiser can only be approved if included in the Register of Organisers of Cultural and Entertainment Events). “This is the infamous decree, or whatever it is, on the organisation of mass events, and everyone is wondering what to do about it“; “…because you have to get permission, and not all events are approved“, “…now almost everything you do, even for free, has to get an approval. And if you are not in the register, you cannot even apply for a touring licence” (©). However, even the presence of an organiser in the state register does not guarantee that they will be allowed to hold an event. We know of several cases where applications for a certificate to organize a cultural or entertainment event were rejected, for example, based on subparagraph 1.12 (“violation of other requirements of legal acts”) of Article 215 (1) of the Culture Code – that is, without explanation.

- unspoken: “blacklists” –

a phenomenon that has existed in Belarus for decades and became widespread after the 2020 protests on a larger scale than ever before. Today, blocklists exist concerning professionals of creative careers – writers, artists, photographers, musicians, historians, museum workers, and tour guides: “…if a person were exposed somewhere, a state institution would not hire them. Most likely, they will not get an invitation to an approved event”; “the lists are long, no one has ever seen them, but it regularly happens that all new artists somehow end up on these lists“; “…we do not have access, for example, … to someone who is not allowed. We must send each candidate [to the Ministry of Culture] … for verification“; “…it all becomes known experimentally. Probably, someone knows for sure that they are on this list, but someone doesn’t know if you don’t have any contact; for example, you are an artist, and you don’t exhibit, then maybe you don’t fully know whether you are there or not” (©).

In the previous report, we wrote about the “stop list” of banned performers in Belarus. Now, we can corroborate it with evidence. Speaking with the Viasna Human Rights Centre about his previous work as a sound operator at the House of Culture in Babrujsk, musician Viačaslaŭ Arkataŭ mentioned censorship by the Ministry of Culture. Officials sent down the list of banned songs and groups, including, for example, the Ukrainian performer Max Barskih, who was on the above-mentioned “blacklist”.

During the reporting period, the monitors recorded for the first time such a type of persecution for dissent as exclusion from creative unions. It is known that ten artists, including Aleś Puškin, Henadź Drazdoŭ (sentenced last May to three years in prison), Uladzimir Ceslier (Tsesler) (living in exile) and several others, were expelled from the Belarusian Union of Artists by the board of the association.

ADDITION TO THE LIST OF “EXTREMIST MATERIALS”

The “List of Extremist Materials” is one of the forms the regime uses to crack down on dissent. Except for isolated types of neo-Nazi, nationalist and radical religious products, most materials are included in the list for political reasons [7]. In January–June 2023, the Ministry of Information had at least 75 materials containing cultural content (books, magazines, music videos, websites, YouTube and Telegram channels, articles, etc.) or related to cultural figures (pages on social media). All these cases are recorded for this monitoring with the wording “designated as extremist material.” It is worth noting, however, that new entries are added to the list under provisions that conflict with the legal standards. They set harmful compliance practices.

- Literature and history

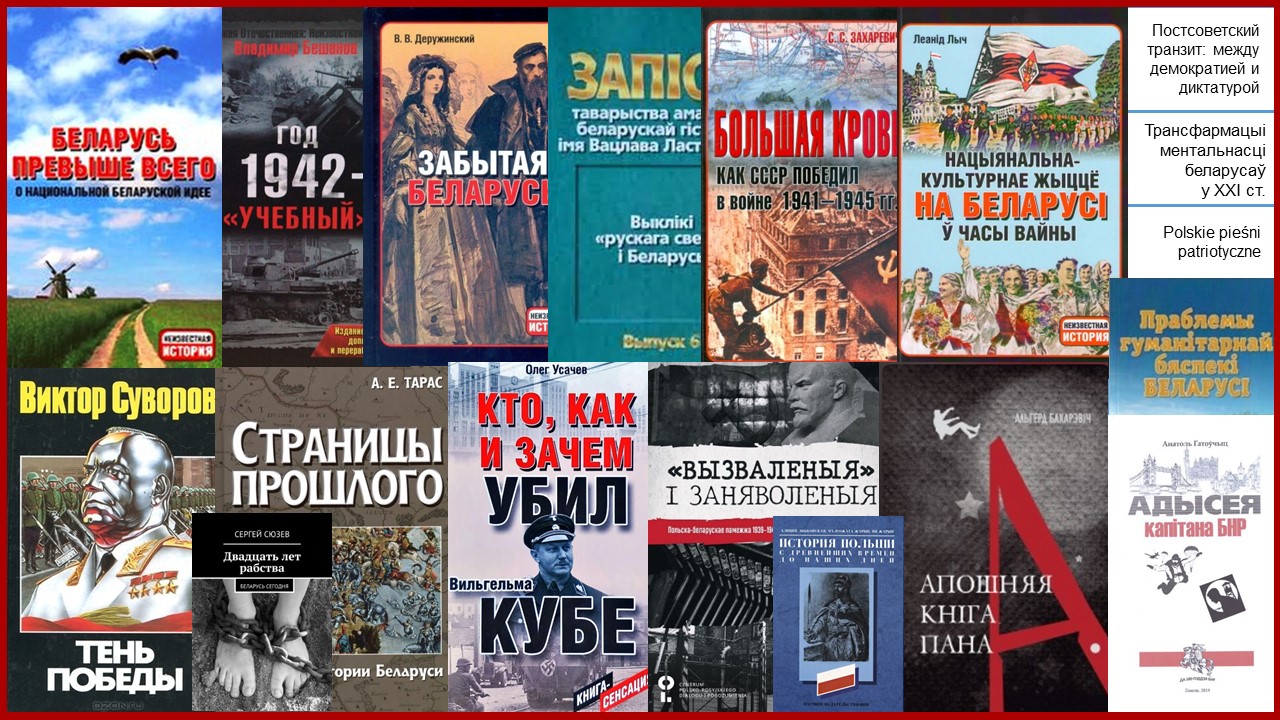

Eighteen books were branded “extremist materials” in the first half of this year. The list includes the works created or edited by Anatol Taras: “Belarus Above All! (About the National Belarusian Idea)”, “Notes of the Vaclaŭ Lastoŭski Belarusian History Amateurs’ Association. “Russian World” Challenges and Belarus. Issue No 6”, “Post-Soviet Transit: Between Democracy and Dictatorship: Collection of Articles”, “Pages of the Past: Articles on the History of Belarus”, “Problems of Humanitarian Security in Belarus: Proceedings of a Conference” and “Transformation of Belarusians’ Mentality in the XXI Century: Proceedings of a Conference” as well as the following books: Uladzimir Biašanaŭ, Schooling in 1942; Vadzim Dzieružynski, Forgotten Belarus; Siarhiej Zacharevič, Big Blood: How USSR Won the War in 1941–1945; Leanid Lyč, National and Cultural Life in Belarus during the War (1941-1944); Viktor Suvorov, The Shadow of Victor”; Aleh Usačoŭ, Who, How and Why Killed Wilhelm Kube”; Aliaksandr Smaliančuk, Liberated and Imprisoned. The Polish-Belarusian Cross-Border Life in 1939-1941 in Documents of Belarusian Archives”; Alhierd Bacharevič, “The Last Book by Mr A “; Anatol Hatoŭčyc, The Odyssey of BNR’s Captain; Siarhiej Siuzieŭ, Twenty Years of Slavery: Belarus Today”; Alicja Dybkowska, Małgorzata Żaryn, Jan Żaryn, The History of Poland from the Ancient Times to Present; Polish Patriotic Songs.

29 books (fiction, journalism, science) have been branded “extremist” since 2021.

Telegram channels about the history of Belarus received the status of “extremist materials”: On 27 February, the Ministry of Information included the Historyja channel (“Kanał pra našu historyju / Channel about our history”) – already designated an “extremist formation” since June 2022 – in the list of “extremist materials”; on 6 April – Belarus history (“History of Belarus in photos and short interesting facts”); on 13 April – local historian and tour guide Cimafiej Akudovič’s Belaruski Babilon (Belarusian history from extraordinary angles). On 6 March, nine issues of the popular science magazine Naša Historyja (Our History) and three issues of the independent scientific, popular science, socio-political and literary-artistic magazine ARCHE, published in 2018-2020, were added to the list.

- Music

On 7 February, the punk anthem of the late 1990s, “Our Home is Belarus“, was declared “extremist“. On 8 February, the video and lyrics of the song “Extremist” (2023) by Daj Darohu! was the second music video that became “extremist” after Baju-Baj (Lullaby) (2020) in August 2021). On 24 February, the list included the VKontakte page of the Belarusian neofolk band Kryvakryž, with their opus magnum album “Malitvy Vainy” (The Prayers of War) (2009) described as “extremely politicised, biased and Russophobic.” On 14 March, the music video “Sumarok – Čerci” by the Sumarok group, containing footage of protests in Maladziečna in 2020, was added to the list. Last year, an article about this video, published in the Rehijanalnaja Hazieta in October 2020, was declared “extremist.” On 31 March, the list was supplemented with the band’s other music video, “Sumarok – 2020“. On 12 April, “2020“, “Tarakan” (demo) and “Papitsot” by Deti Khrushchevok, as well as its YouTube channel and accounts on social media, were declared “extremist”. On 26 April, another Ukrainian song, “Ah, Bandero!” appeared on the list. In November 2022, “Our Father is Bandera, Ukraine is Mother” was deemed “extremist”. On 25 May, four songs of the faceOFF group: “Pora!!!“, “Guardians of the Galaxy“, “Hate“, and “Viasna“, as well as its VKontakte page, were added to the list. On 23 June, the YouTube channel Tyapin CREW, the website and social media accounts of rapper Andrej Ciapin (Tyapin) were added to the list.

- Cinema

On 24 February, the Salihorsk District Court of Minsk Region, among other things, designated the VKontakte group dedicated to the 2013 feature film “Žyvie Bielarus! || Viva Belarus!” as “extremist material”. “The first feature film about contemporary Belarus in the Belarusian language”, as the group’s description says.

- Belarusian language and culture, in general

On 7 April, the Maladziečna-based independent newspaper Rehijanalnaja Hazieta, which covered the topics of culture, history and language, was designated as “extremist material”. In operation since 1995, the Belarusian-language newspaper had to stop its printed version in July 2021 after searches in the editorial office and journalists’ houses. The editor-in-chief Aliaksandr Mancevič is a political prisoner. On 26 April, Euroradio.fm website was added to the list. The media outlet was designated an “extremist formation” in July 2022. On 22 May, the Telegram channel Tolki pra movu (About Language Only) (“A channel for those who think and care about the language”) appeared on the list. On 8 June, the website (and social media channels) of the Belarusian Association of Journalists (branded as an “extremist formation” last February) was added to the list. On 28 June, the website and Telegram channel of the cultural and educational portal about Belarus Budźma Bielarusami! appeared on the list of the Ministry of Information. The information and entertainment show “Heta Minsk, Dzietka!“ (This Is Minsk, Baby!)” on YouTube was also put on the list of “extremist materials”.

ISSUES OF STATE POLICY IN THE SPHERE OF CULTURE

At the end of June, media reported about the removal from Belarus of two historical and cultural values: the shrine of St. Felician the Martyr – a relic from the Minsk Cathedral, and the Brest (Radziwill) Bible – the rarest West Slavic palaeotype.

The media articles questioned the legality of relics’ export. Still, the state authorities have not provided a public explanation until now, nor do we know whether an official investigation is underway and what measures are being taken [during the preparation of the material for publication it became known that the story had a continuation] [8].

The state continues the policy aimed at de-Belarusisation (discriminatory attitude toward the Belarusian language, persecution for Belarusian identity) and promoting the “Russian World” culture and ideology. It fights with “Western values” and culture (LGBT literature, St. Valentine’s Day, Halloween, Huggy Wuggy, etc.), Polish-Lithuanian heritage and develops study guides for promoting patriotic education of the younger generation and the unified state policy of historical memory. The state also shuts down private educational institutions and persecutes representatives of academia, religious organisations and communities, political parties and other associations.

New steps are made to strengthen control in the cultural sector:

- On 1 January, Resolution No. 582 “On Sightseeing Services” came into force, regulating the activities of tour guides and guides-interpreters. Now only specialists who have passed certification can work in the profession. Those with criminal convictions under several (politically motivated) articles cannot pass certification. Accordingly, some specialists see their previously issued attestation certificates cancelled. Among those deprived of the right to work are also without administrative punishment, but they were allegedly complained against or “do not meet the moral standards of a tour guide”. According to the new rules, only museum employees can provide sightseeing services.

- During the period under study, not only tour guides but also craftspeople underwent a recertification procedure. To remain in a more favourable taxation system (to pay the smaller fixed craft fee rather than a tax on professional income), craftspeople had to have their status confirmed before 1 July in the local administration’s ad hoc commission. Under the requirements, they had to present their products at specialised state-sponsored venues (exhibitions and fairs). The aim was reportedly to reduce the number of artisans by 50 per cent. As with the right to organise cultural and entertainment events, restrictions for tour guides and guides-interpreters, this new procedure is a legal mechanism for excluding people from a particular service branch.

- On 6 January, the law “On Restricting Exclusive Rights to Intellectual Property Items” legalised for two years the parallel import and pirated use of musical and audiovisual works, computer software and other intellectual property items without the consent of the rights holders and payment of a royalty.

- On 24 March 2023, the Resolution of the State Property Committee of the Republic of Belarus “On the Transfer of Names of Geographical Objects from Belarusian and Russian into Other Languages” was published and came into force. It regulates replacing geographical names transliterated from the Belarusian language with Russian-based transliterations. Essentially, it leaves no space for transliteration in the Belarusian Latin alphabet. The transliteration system for geographical names was “improved” following a massive campaign of pro-governmental activists, tirelessly fighting against the national identity-oriented heritage of Belarus, including the Belarusian language. Under this resolution, the replacement of names – in particular, the replacement of signboards at city transport stops – has begun.

The procedure regulating the operation of civilian drones makes aerial photography as tricky as possible. On 4 June, the new rules for using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) came into force, setting more restrictions. Almost all UAVs are subject to state registration. Each operator must undergo training, obtain permission to use airspace, take aerial photographs and carry certain documents when flying.

- 42 semi-structured interviews were conducted with Belarussian cultural figures from March to June 2023.

- (©) – Quotes from the study on hidden repression.

- Information on the number of cultural workers in detention is not definitive, as not all of them are immediately known.

- One of the types of punishment under criminal articles is restriction of liberty without referral to an open-type correctional institution.

- Aleś Puškin’s death became known during the preparation of this report.

- https://www.sb.by/articles/markevich-predatelyam-ne-mesto-na-stsene-no-raskayavshimsya-daetsya-vtoroy-shans.html.

- https://humanconstanta.org/razbiraemsya-s-ekstremistskimi-spiskami-chto-vxodit-v-ekstremistskie-materialy/.

- https://t.me/spadczyna/9249.